"Many depictions of painters at work have survived. Initially, St. Luke painting the Madonna was portrayed predominantly. These paintings must contain reliable information with regard to the studio practices of the period in which they were created, or otherwise the contemporary viewer would not have recognized the representation. The same applies to the palettes shown in these paintings. When analyzing a large random sample of palettes depicted in paintings, such consistency emerged in the shape and the arrangement of the paint that one may safely argue that no well-trained painter would think of painting a fake palette.

"Generally speaking and based on studio scenes, it can be stated that prior to 1400 painters worked with separate paint trays, each of which held prepared paint of one color or hue. The first depictions of palettes stem from about 1400. They most closely resemble bread boards with a handle, used by the painter to hold the palette. Someone must have come up with the idea of making a hole in the handle that would be big enough to put one's left thumb through (fig. 1). The advantage of this innovation is obvious: it enabled the painter to support the palette easily in a horizontal position on the thumb; he could then hold other tools (including the maulstick while painting) with the remaining fingers of the same hand. Next, we see that the hole is no longer found in a handle-like protrusion from the palette, but that it is situated in the flat of the palette itself.

fig. 1 Saint Luke Painting the Virgin and Child

fig. 1 Saint Luke Painting the Virgin and ChildFollower of Quinten Metsys

between 1518 and 1522

Oil on oak wood, 113.7 34.9 cm.

National Gallery, London

"The earliest palettes were small. Although they increased in size in the course of the sixteenth century, painters' palettes remained relatively small up to the early nineteenth century: 30 to 40 cm long. Only during the nineteenth century did they grow to the size of half a tabletop, sometimes made in such a way that they were adapted to the curve of the painter's body, in order to gain extra space for mixing paint."Van der Wetering, Ernst. Rembrandt: The Painter at Work (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 141-143.

The number of pigments available to the seventeenth-century Dutch painter werea paltry few indeed when compared to those available to the modern artist. While the current catalogue of one of the most respected color producers (Rembrandt) displays more than a hundred pigments, about only 20 pigments have been detected in Vermeer's oeuvre.Hermann Kühn, "A Study of the Pigments and Grounds Used by Jan Vermeer," Reports and Studies in the History of Art, National Gallery of Art, 1968, 154–202. This examination of Vermeer's pigments is principally based on Kühn's study. Due to the discreet number of paint samples taken, which were only from the outer edge of the canvas, the study provides only partial knowledge about which pigments Vermeer used and how he employed them. Recent studies have been integrated into this study.

Of these few pigments only ten seemed to have been used in a more or less systematic way.

In Vermeer's time, each pigment was different in regards to permanence, workability, drying time, and means of production. Furthermore, many of these pigments were not mutually compatible and required separate or specific methods of application. This study will examine the history and origins of each pigment, as well as their applications by Vermeer and his contemporaries.

Vermeer's principal pigments

A significant lacuna in the palette of seventeenth-century painters was the lack of the so-called "strong colors." Only a handful of bright, stable and workable colors existed. Mixing colors to create new tints did little to alleviate the problem. When pigments are physically mixed together, the new color is inevitably less brilliant than either one of the original components and, more importantly, more importantly, some older pigments were not even compatible

A Painter in his Studio (detail)

Anonymous pupil of Rembrandt van Rijn

Rembrandt van Rijn

Oil on panel, 64.5x 53 cm.

Kremer Collection

The Art of Painting (detail)

The Art of Painting (detail) Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1668

Oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

A detail of Vermeer's Art of Painting which represents an idealized painter at work portraying the muse of the arts, Clio.

One thorn in the side of the seventeenth-century painter was the chronic shortage of strong, opaque yellows and reds which could be used to model form with relative ease. The exceptionally brilliant red and yellow cadmiums, now obligatory paints in any contemporary painter's studio, were not commercialized until the 1840s. For centuries the only strong opaque red adapted for modeling was vermilion. Vermilion is a very opaque pigment with excellent handling properties but it nonetheless possesses a fiery orange undertone and must be glazed to protect it from degrading. Strong yellows, in particular, were scarce and the only brilliant green was the problematic verdigris. To overcome the lack of suitable purple pigments and economize, artists had learned to first model form in tones of ultramarine and white and then glaze over the dried layer of red madder obtaining a lively purple tint.

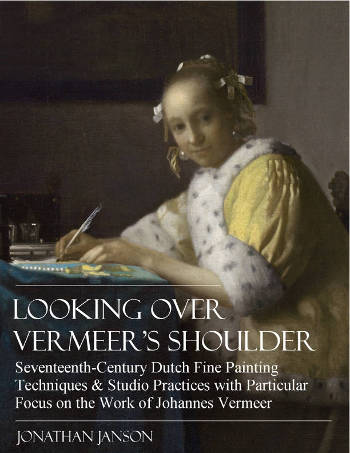

LOOKING OVER VERMEER'S SHOULDER

The complete book about Johannes Vermeer's and 17th-century fine-painting techniques and materials

by Jonathan Janson | 2020

Enhanced by the author's dual expertise as both a seasoned painter and a renowned authority on Vermeer, Looking Over Vermeer's Shoulder offers an in-depth exploration of the artistic techniques and practices that elevated Vermeer to legendary status in the art world. The book meticulously delves into every aspect of 17th-century painting, from the initial canvas preparation to the details of underdrawing, underpainting, finishing touches, and glazing, as well as nuances in palette, brushwork, pigments, and compositional strategy. All of these facets are articulated in an accessible and lucid manner.

Furthermore, the book examines Vermeer's unique approach to various artistic elements and studio practices. These include his innovative use of the camera obscura, the intricacies of his studio setup, and his representation of his favorite motifs subjects, such as wall maps, floor tiles, and "pictures within pictures."

By observing closely the studio practices of Vermeer and his preeminent contemporaries, the reader will acquire a concrete understanding of 17th-century painting methods and materials and gain a fresh view of Vermeer's 35 masterworks, which reveal a seamless unity of craft and poetry.

While the book is not structured as a step-by-step instructional guide, it serves as an invaluable resource for realist painters seeking to enhance their own craft. The technical insights offered are highly adaptable, offering a wealth of knowledge that can be applied to a broad range of figurative painting styles.

LOOKING OVER VERMEER'S SHOULDER

author: Jonathan Janson

date: 2020 (second edition)

pages: 294

illustrations: 200-plus illustrations and diagrams

formats: PDF

$29.95

CONTENTS

- Vermeer's Training, Technical Background & Ambitions

- An Overview of Vermeer’s Technical & Stylistic Evolution

- Fame, Originality & Subject Matte

- Reality or Illusion: Did Vermeer’s Interiors ever Exist?

- Color

- Composition

- Mimesi & Illusionism

- Perspective

- Camera Obscura Vision

- Light & Modeling

- Studio

- Four Essential Motifs in Vermeer’s Oeuvre

- Drapery

- Painting Flesh

- Canvas

- Grounding

- “Inventing,” or Underdrawing

- “Dead-Coloring,” or Underpainting

- “Working-up,” or Finishing

- Glazing

- Mediums, Binders & Varnishes

- Paint Application & Consistency

- Pigments, Paints & Palettes

- Brushes & Brushwork

Moreover, strong colors were not always readily available in the unpredictable marketplace and had to be used with utmost economy. For example, natural ultramarine, the most precious of all blues for the artist, had become so expensive that painters usually used it as a glaze over a monochrome underpainting. Vermeer employed natural ultramarine in this manner.

Economic considerations played a decisive role in the artist's working procedures. If the complete range of pigments, each already ground in oil, had to be available for use at all times, large amounts of paint would go to waste. Metal tubes were employed only in the mid-nineteenth century. Unused paint from a single painting session was kept temporarily in pig's bladders or the entire palette could be submerged in water overnight to prevent contact with oxygen which induces drying.

It is highly unlikely that Vermeer would have had all available pigments on his palette in any given work session. Painters were known to set out specific palettes each day, according to the passage they planned to paint. The wooden palette above represents the seven principal pigments which Vermeer commonly employed.

The "working palette" of Vermeer

- lead white

- yellow ochre

- vermillion

- madder lake

- green earth

- raw umber

- ivory or charcoal black

The Materiality of Color

drawn entirely from: "Mining for Color: New Blues, Yellows, and Translucent Paint" by Barbara H. BerrieBarbara H. Berrie, "Mining for Color: New Blues, Yellows, and Translucent Paint," Early Science and Medicine 20, no. 4-6 (2015): 308, https://brill.com/view/journals/esm/20/4-6/article-p308_2.xml?lang=en.

Written descriptions of artists' materials and practice give only parts of the picture. Sources may include colors and prices, but are often imprecise in terminology and silent on the manner of use. Inventories of color-sellers stores are helpful in judging the range available at a specific time and place but only seldom identify who used the supplies or how they were employed. Treatises written for painters describe the core palette, and often include some information on how to prepare supports and use pigments, but often they only allude to practice and technique. Trade accounts and bills of lading attest to the worldwide trade in precious materials for art-making, such as colors and resins that were imported from afar, but the local, the quotidian and the secret are more difficult to learn about, though equally important. Although the guild structure would appear to have inhibited artistic exploration through regulations and requirements for workshop output, even the strictest rules did not, in the end, inhibit the use of novel materials. Personal style and individuality flourished and paved a path for others to follow and actual practice— demonstrated by close observation and chemical analysis—was diverse and even idiosyncratic The ways paint and color were handled showed even greater variety. Oil painting allowed colors to be mixed on the canvas and blended while wet, so artists could use gentle gradations in tone to create chiaroscuro and the effect of sfumato. Translucent paints could be prepared, and colors adjusted using thin glazes or "veils" of color to build rich tones and subtle shading. In the sixteenth century, artists explored and exploited the full potential for creating color and texture through the use of different pigments and brushwork, employing impasted strokes and scumbles of opaque color in addition to glazes. Even the most adventurous artists were, however, limited by what was available to them. Thus our knowledge of trade in materials, practice and innovation in color-making provides an underlying context for the interpretation of novelty in painting practice.

Almost all of the materials used for painting, whether natural or synthetic, required some kind of processing from the raw state; methods for preparing certain colorants involved many steps, which cumulatively contributed to their cost. The rarity and expense of some meant that the production of certain colors was limited in scale and their use was restricted to special decorative purposes. Some were employed for medicines and luxury items such as perfumes and cosmetics, while others could only be differentiated from painters' colors based on the scale of production and in particular the purity of the product.

Newly developed means of sourcing minerals provided abundant supplies of certain elements necessary to the color-making process. Mining and the production of particular metals in combination with technological advances in manufacturing opened opportunities to add new colorants and thereby improved paint-making. Two pigments, smalt and Naples yellow, coming to painters via the ceramic and glass industries, became established on oil painters’ palettes in the mid-sixteenth century. Smalt is a potassium-containing (potash) glass that is colored deep blue owing to the presence of cobalt. Naples yellow, an oxide of lead and antimony, is a warm, rich, quite stable and rather intense yellow. A very different material, mineral oil (or naphtha) was mined from sources that were found in the sixteenth century. Using it as a diluent allowed artists to spread paint thinly, to use the translucency of oil paints to make gradations in hue to blend thinner glazes of paint, and make clear varnishes. The relationship between availability of new ores and the look of paintings solicits further investigation.

or anything else that isn't working as it should be, I'd love to hear it! Please write me at:

or anything else that isn't working as it should be, I'd love to hear it! Please write me at: