A Lady Standing at a Virginal

(Staande Virginaalspeelster)c. 1670–1674

Oil on canvas, 51.7 x 45.2 cm. (20 3/8 x 17 3/4 in.)

National Gallery, London

inv. 1383

The textual material contained in the Essential Vermeer Interactive Catalogue would fill a hefty-sized book, and is enhanced by more than 1,000 corollary images. In order to use the catalogue most advantageously:

1. Scroll your mouse over the painting to a point of particular interest. Relative information and images will slide into the box located to the right of the painting. To fix and scroll the slide-in information, single click on area of interest. To release the slide-in information, single-click the "dismiss" buttton and continue exploring.

2. To access Special Topics and Fact Sheet information and accessory images, single-click any list item. To release slide-in information, click on any list item and continue exploring.

The window

The Lute Player (detail)

Hendrick Maertensz. Sorgh

1661

Oil on canvas, 52 x 39 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

While many Dutch painters delighted in depicting bits and pieces of city life outside the windows of their interior scenes, Vermeer avoids alluding to the world outside his carefully assembled mise-en-scène. This must have been a deliberate choice since even though his studio was above street level, some sort of architectural element would have been visible.

A Vermeer writer wrote that the artist permits us to see on the opened lid of the virginal what we cannot see through the closed window. In fact, the size and shape of the window's lower casement reflect those of the lid. Moreover, the gradation of pale green to light lemon-yellow of the window—created with shades of green earth and lead-tin yellow—, which is far more apparent when viewing the original painting, recalls the color scheme of the landscape. Vermeer may have intended some sort of visual pun, perhaps the echo of color and music, to reinforce the painting's theme.

The gilt-framed painting on the back wall

The intricately carved French frame is the only object in the scene that does not overlap with any other, giving it a life of its own, almost independent from its surroundings. Vermeer may have chosen such a glittering frame in order to contrast with the somber black geometry of the Cupid's ebony frame.

The conventional-looking landscape has been associated by art historian Gregor Weber with a Mountain Landscape with Travelers by the Delft artist Pieter Groenewegen, a friend of Vermeer's father with whom Vermeer must have been acquainted. If Vermeer did indeed base his picture-within-a-picture landscape on Groenewegen's work, he adapted it to his needs. One can see that only the right half of Groenewegen's composition was utilized so it would fit into the gilt frame. Billowing clouds were added, perhaps, to echo the clouds of the virginal's landscape and the puffy silk sleeves of the standing musician. The castle which silhouettes against the sky was removed. Surprisingly, a stylized version of Groenewegen's landscape appears again in full on the lid of the virginal.

Until recently, experts had largely written off the landscape pictures-within-pictures in Vermeer's interiors as decorative fillers with no significant iconographic connection to the scenes which unfolded beneath them. However, art historian Elise Goodman submits that like versifiers and composers of the 17th century, Vermeer utilized his framed landscapes to nuance the story of the figures. The idea that woman was a "masterpiece of nature to be admired, possessed and displayed appeared in countless poems, songs and tracts on beautiful women in 17th-century Europe."

What seems at first glance to be a patient rendering of a gold frame is, on close observation, a series of quickly applied dots and dabs of thick light yellow paint which appear to dance upon a deeper ocher-toned base. Vermeer expert Walter Liedtke likened the rendering of the frame to "the lady's rhythmic curls, pearls, ribbons and the lace trim on her sleeve (its billowing combination of blue and white is echoed in the landscape's sky)." One might also envisage a gay musicality, perhaps not distant from the crisp staccato effect produced by the music of virginal.

The ebony-framed Cupid

Dutch art historian Eddy de Jongh was the first to point out that the ebony-framed Cupid with a raised arm may have been inspired by an engraving contained in Otto van Veen's popular emblem book Amorum Emblemata published in 1608 in Antwerp. Van Veen's Cupid holds aloft a small card on which appears a Roman numeral "I" which refers to the emblem's caption: "a lover ought to love only one." By including it, De Jongh believes that Vermeer most likely alludes to the concept of love which includes fidelity, although he does not know if the admonition is directed toward the standing musician or the spectator.

Curiously, the upheld card in Vermeer's painting is blank which, if intentional, may have meant to further nuance the meaning of the story, although the number has possibly degraded with time or was removed by incautious restorations of the past. In any case, the pot-bellied Cupid of Vermeer's composition resembles not only Van Veen's engraving but similar standing puttos that appear in the classicist works by the Alkmaar artist Cesaer van Everdingen, a well-known history painter of the time.

Likely, Vermeer's Cupid was not an artistic fabrication but a real painting mentioned as "a Cupid" in the inventory of his widow's possessions in 1676. Although, like other props included repeatedly in Vermeer's interiors, Van Everdingen's work must have held a certain significance for the artist since it also appears in the background of the earlier A Maid Asleep, Girl Interrupted in her Music and, before it was eventually painted over by a later hand, the Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window.

Who posed for the painting?

We have no record of who posed for this picture. In any case, it was certainly not made to function as a portrait. Vermeer seems uninterested in defining the young woman's individual physiognomy with any precision, although her inflexible expression mesmerizes the spectator and effectively draws him into the hollow cube of space that she confidently inhabits.

Curiously, the shadows of the figure's face are rendered with an unlikely dull green tone—made with the lackluster pigment green earth—readily visible when observing the original. Vermeer used the same tone in other late paintings in an analogous manner. Painters of the time invariably employed brown tints for darker flesh shadows. Vermeer's unusual technique was utilized by a few nearby Utrecht Caravaggists, but no one used it so assiduously as Vermeer. Vermeer specialist John Michael Montias hypothesized that the young Vermeer may have studied in Utrecht.

The pearl necklace

As a painter and consummate observer of nature, Vermeer must also have been fascinated by the visual qualities of the pearl. Throughout his career, he experimented with different techniques to render their unique pearlessence. Perhaps the most daring technique can be seen in this picture. If carefully observed, the outer edge of the necklace has barely been indicated by a band of thin, grayish paint. The blurred contour suggests the pearl's transparency while the thick globular highlights inform us of the reflective quality, spherical form and position of each pearl.

Since ancient times, the pearl has been among the most valuable of all gems and a potent symbol of unblemished perfection. In a manner analogous to the pearl's origin in an oyster, Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty, love and sexual desires, was born from a marine conch. In classical Rome, pearls were worn for their curative powers and only persons above a certain rank were allowed to wear them. The Latin word for pearl literally means "unique," attesting to the fact that no two pearls are identical. And last but not least, throughout history, pearls have been worn as a symbol of wealth.

The present work, as iconographers frequently pointed out, seems to be much about love. Cupid is represented two times, once conspicuously in the background picture and a second time, hardly noticeable, on a Delft tile just to the left of the lady's silk gown. The virginal was also strongly associated with love. Thus, it is clear that Vermeer could have ignored its noble lineage. As the rediscoverer of Vermeer, Thoré Bürger, who owned the picture for some years, wrote: "Happily, with Vermeer, one only discovers these small allegorical niceties after one has understood everything simply from the expressions of the personages."

The elegant satin garment

The standing young musician wears a formal satin—not silk— garment called a tabbaard, a combination of a stiffened satin gown and a matching bodice called a tabbaardslijft. This ensemble was characteristic of the upper class fashion during that time.

The tabbaardslijft was notable for its construction, as it was heavily boned to give it structure and shape. This boning created a rigid form that helped maintain the desired silhouette. However, this also made the tabbaardslijft quite uncomfortable, limiting its use to formal occasions where appearance took precedence over comfort.

Noting the utmost simplicity with which the gown is depicted, the art historian Albert Blankert likened it to a classical fluted Greek column. It has a unique pale-yellow tone different from the icy gray of the bodice and comprises one of the very few satin gowns painted in 17th-century Netherlands that is not surrounded by a dark background. Vermeer's wife, Catharina Bolnes, possessed one such gown made of black cloth, which was probably meant for mourning.

An Interior with Two Elegant Ladies Making Their Toilet, Together with a Maid Making the Bed and a Dog on a Chair (detail)

Attributed to Jacob Ochtervelt

1670s

Oil on canvas, 80.5 by 66.5 cm.

Private collection

Both satin and silk are fabrics that have been used for centuries, valued for their luxurious texture and aesthetic appeal. However, they have distinct differences in terms of their origins, characteristics, and production.

Silk is a natural protein fiber obtained from the cocoons of silkworms. Satin is not a type of fiber but rather a weave, which can be made from various fibers, including silk, polyester, acetate, and nylon. The specific characteristic of satin is its high-gloss, shiny surface, which results from the way the fibers are woven.

Satin is believed to have originated in China during the middle ages. Its name comes from Zayton, the medieval Arabic name for the Chinese port city of Quanzhou. This city was an active trading port, and satin was one of its primary export products. The fabric eventually made its way along the Silk Road to Europe, where it grew in popularity, especially among the elite.

The virginal

P. C. Hooft "Sy blinkt, en doet al blincken" (detail)

Emblemata Amatoria, 1611,

in Werken, Amsterdam, 1671

National Gallery of Art, Washington

The virginal was an instrument greatly admired by the Dutch upper class during the mid-17th century. Its lyrical yet restrained tones underscored a gradual refinement in taste that had accompanied the explosive increase in wealth of the Netherlands. Solo virginals music was quite common, where a performer could show their technical skills and interpretation through intricate and expressive pieces. Many well-known composers of the period, such as Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (from Delft), Giles Farnaby and Peter Philips, wrote compositions specifically for keyboard instruments like the virginal. These compositions often featured variations on popular tunes, dance forms and elaborate ornamentation. Moreover, the virginal could be combined with other instruments, such as the violin, cello, flute, or voice, to create harmonious ensembles, such as those we see in Vermeer's Concert. These ensembles would perform a variety of music, including vocal and instrumental pieces, allowing for a diverse musical experience and a chance for young people to mix.

Even though Vermeer enjoyed economic security for most of his career, when this picture was painted he had run into serious economic difficulties brought on by the French invasion and subsequent crash of the art market. Thus, at the time the Lady Standing at a Virginals was painted, it is unlikely that he possessed such a luxury item. However, the resourceful painter had numerous channels that would have allowed him to observe or borrow one.

Circumstantial evidence links the painter to one of the most illustrious art connoisseurs and men of culture in the Netherlands, Constantijn Huygens, who was himself a composer of great stature. Diego Duarte, who in turn was connected to the illustrious Huygens family, was an immensely rich Antwerp banker and possessed "a young lady playing the clavecin, with accessories, by Vermeer." Duarte was an accomplished organist.

The velvet-upholstered chair

The Duet (detail)

Frans van Mieris

1658

Oil on panel, 31.7 x 24.7 cm.

Staatliches Museum, Schwerin

This specific type of chair with a light blue velvet upholstery is represented only one time in Vermeer's interiors even though similar chairs appear in a number Dutch genre interiors such as those of Frans van Mieris.

Critics have suggested that the empty chairs which populate Vermeer's single-figure interiors allude to an absent male counterpart, most likely a lover. The blue natural ultramarine pigment employed in the darker areas of the chair's shadows has somewhat deteriorated and now appears too light.

The landscape in the gilt frame

Mountain Landscape with Travelers

Pieter Groenewegen

c.1658–1660

Private collection, Amsterdam

Art historian Gregor Weber, who has studied the so-called pictures-within-pictures incorporated in the background of Vermeer's compositions, was the first to point out that both the landscape on the lid of the virginal and the landscape in the gilt frame on the back wall are derived from a single image. Other than its overall design and the successive light and dark layers of rocks and trees, the roofs of the houses and the waterfalls of the two landscapes are virtually identical. Weber concluded that they were both based on a single painting.

By coincidence, Weber saw a photograph of a Mountain Landscape with Traveler by the Delft painter Anthonisz. van Groenewegen. He subsequently informed two art dealers from The Hague (John and Willem Jan Hoogsteder) of his finding who were amazed when they discovered they were the owners of the very picture in question.

Using computer montage, Weber further analyzed the two landscapes in Vermeer's painting in reference to the real Van Groenewegen. Although it was evident that Vermeer had used some poetic license in adapting Van Groenewegen's picture to his expressive exigencies, the coincidences were so compelling that they swept away any reasonable doubt.

What remains to be understood is exactly what Vermeer intended by such pictorial trickery. The two landscapes were possibly meant to create a visual echo to complement the work's musical theme. Visual echoes, some obvious and some subtle, seem to be a part of Vermeer's pictorial repertoire. One example is the curling locks of the youthful Guitar Player that echo the dangling foliage of the large tree in the landscape behind her. Another echo is created by the snow-white cap of the maid and the billowing clouds of the landscape behind her in The Love Letter.

The free-flowing style of the veins of the marble floor

In his late years, Vermeer moved away from a faithful recording of natural phenomena towards stylization. The remarkably free-flowing brush strokes of the veins of the marble floor tiles reveal the painter indulging himself in the act of painting, enjoying the movement of his own hand rather than meticulously recording the appearance of the tiles.

The floor tiles in Vermeer's interiors exhibit remarkable accuracy in perspective, aligning with the area of minimal distortion. While the smaller ceramic-tiled floors in his early interiors show minor imperfections, these may stem from the challenges of hand-painting such tiny tiles, particularly those in the background. This contrasts with De Hooch's interiors, where floor patterns on one side of a figure might not match those on the other side. Vermeer's work, however, consistently avoids this anomaly.

The Delft tiles

Other than the two white wine jugs portrayed in his earlier compositions, these hand-painted baseboard tiles were the only homage Vermeer paid to the renowned Delft porcelain production. The humble tiles, which were so cheap that they served as ballast for ships, protected the plaster walls from the daily assault of brooms, mops and scrubbing brushes. Each tile was hand-decorated with scenes of daily life including children's games such as walking on stilts or flying kites.

Art historian H. Rodney Nevitt Jr. pointed out that the Cupid tile just to the left of the woman's skirt resembles a print in Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft's Emblemata amatoria which plays on the conventional comparison between fishing and courtship. Other elements that reinforce the theme of love are the large painting of Cupid in the black frame and the virginal.

Delft baseboard tiles, created in 17th-century Delft, Netherlands, were ceramic pieces distinguished by their iconic blue and white designs. Crafted through tin-glazing, a process involving a white tin oxide-based glaze and cobalt blue pigments, these tiles served both aesthetic and functional purposes in Dutch interiors. Acting as protective skirting elements, they guarded walls from moisture and damage in areas prone to spills, such as kitchens and corridors. Beyond their practical role, these tiles added elegance to spaces while also being accessible to a wide range of households. Their production was centered in Delft and extended to other towns, resulting in a broad distribution within the Netherlands and beyond. The popularity of Dutch decorative arts led to their export across Europe, and even to the Oreint. in significant quantities, where they found widespread use. These tiles served a dual purpose during their journey to the East. They were not only highly valued commodities for trade but also practical ballast for Dutch ships. This practice of using the tiles as ballast ensured stability and balance for the vessels during their long voyages to distant destinations.

The billowy sleeve of the lady' upper garment

The puffy satin sleeve of the standing musician constitutes a veritable tour de force of brushwork. The brilliant chiaroscuro effect of the silken material is evoked by deftly placed dots, dabs and dashes of light-toned paint over a light gray base. Some writers believe that this technical innovation was a consequence of the artist's need to abbreviate the painting process for commercial motives, while others see an accommodation to the growing taste for French mannerism which had begun to influence Dutch painting.

Not all critics agree that the present painting and the Lady Seated at a Virginal were conceived as a pendant, although, following Walter Liedtke's reasoning, the National Gallery in London has equipped them with identical frames and now exhibits them side by side.

The background wall

As in no painting, except perhaps for the earlier Woman with a Pearl Necklace, does the background wall play such a determining role in the composition, simultaneously defining the intensity and direction of the incoming light as well as establishing the particular atmosphere suited for the story at hand. The crisp morning light enters through a large fully opened window, raking over the uneven surface of the wall from left to right with passionless objectivity. The objects hung on the wall cast crisply defined shadows to their right. Here and there, slight variations in gray suggest imperfections in the wall's whitewashed surface. The principal objects stand out distinctly from each other, framed by open expanses of light-gray background wall. As Walter Liedtke observed, "Vermeer constructed similar spaces in earlier pictures and yet here for the first time, it seems possible to walk around the figure, joining her at the instrument from either side. This freedom of mobility (or permission to sit in the chair), together with the crisp white light exquisitely described on every surface, makes the viewer feel that nothing is hidden from view."

Although Vermeer's skill in managing color and tonal value (the degree of brightness or darkness of a given color) makes the wall look intrinsically white throughout, the tones of light gray paint that are used to describe it must vary considerably in brightness to produce the sensation of the gradual falloff of light from left to right. In the illustration above, square a. between the window frame and the gilt-framed landscape has been copied and pasted (b. and c.) into two different positions to demonstrate just how different the difference must be to produce the desired effect.

special topics

fact sheet

- Signature

- Date

- Provenance

- Exhibitions

- Technical description

- The painting with its frame

- How big is this picture?

- Download High-Resolution Image at WikiMedia

- National Gallery Super-zoom image

- Google Art Project Super-zoom image

- Historic timeline of the year(s) Vermeer created this painting

- Related artworks

The signature

Inscribed at left below the upper edge of the virginal: IVMeer (IVM in ligature).

(Click here to access a complete study of Vermeer's signatures.)

Dates

c. 1670

Albert Blankert, Vermeer: 1632–1675, 1975

c. 1672–1673

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., The Public and the Private in the Age of Vermeer, London, 2000

c. 1670–1672

Walter Liedtke, Vermeer: The Complete Paintings, New York, 2008

c. 1672–1674

(Click here to access a complete study of the dates of Vermeer's paintings).

Technical report

The fine, plain-weave linen support has a thread count of 14 x 14 per cm². The original tacking edges have been removed. Cusping is visible along top and bottom and very faintly along both sides. The support has been lined. The double ground consists of a pale gray beneath a pale warm gray buff. The first layer contains lead white, chalk and charcoal black; the second contains lead white, chalk and a red-brown earth.

The flesh color was painted with green earth over a pink layer; the shadows with two additional layers, a mixture containing green earth followed by a deep red shadow. The blue upholstery was underpainted with a gray-blue layer; the highlights were modeled with a blue, then a pale blue layer, and the shadows with gray. The outlines of the tiles at the bottom of the wall were scratched in the wet paint. A pinhole by which Vermeer marked the vanishing point is visible in the paint layer on the sleeve of the woman's dress.

There is some abrasion in the three paintings within the painting, in the lady's right cheek and the dark blue of her tunic, and in the blue upholstery. The ultramarine pigment in the darker blues of the chair has deteriorated.

* Johannes Vermeer (exh. cat., National Gallery of Art and Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis - Washington and The Hague, 1995, edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr.)

Provenance

- (?) Diego Duarte, Antwerp (1682, sold before 1691), or (?) Dissius sale, Amsterdam, 16 May, 1696, no. 37, or (?) Nicolaes van Assendelft, Delft (before 1692) and widow Van Assendelft, Delft (1711);

- (?) sale, Amsterdam, 1714, possibly no. 12;

- Jan Danser Nijman sale, Amsterdam, 16 August, 1797, no. 169 (to Bergh);

- (?) Edward Solly, Berlin and London, before 1844;

- Edward William Lake sale, London, 11 July, 1845, no. 5 (to Farrer);

- J.T. Thom sale, London, 2 May, 1855, no. 22 (to Grey);

- Thoré-Bürger (Etienne Joseph Théophile Thoré), Paris (before 1866-d.1869);

- Paul Lacroix, Paris (1869–1884, inherited from Thoré-Bürger);

- widow Lacroix, Paris (1884–1892);

- Thoré-Bürger sale, Paris, 5 December, 1892, no. 20 (to Bourgeois Frères, Paris, and/or Lawrie & Co., London);

- purchased in 1892 by The National Gallery, London (inv. 1383).

Exhibitions

- Paris 1866

Exposition rétrospective tableaux anciens empruntés aux galeries particulières

Palais des Champs-Elysées

6, no. 108. - Amsterdam 1867

Katalogus der tentoonstelling van schilderijen van oude meesters

Arti et amicitiae

39, no. 274 - Paris September 24–November 28, 1966

Dans la lumière de Vermeer

Musée de l'Orangerie

no. 12 and ill. - The Hague June 25–September 5, 1966

In het licht van Vermeer

Mauritshuis

no. 11 and ill. - London 1976

Art in Seventeenth-Century Holland

National Gallery

92–93, no. 116 and ill. - Washington D.C. November 12, 1995–February 11, 1996

Johannes Vermeer

National Gallery of Art

196–199, no. 21 and ill. - The Hague March 1–June 2, 1996

Johannes Vermeer

Mauritshuis

196–199, no. 21 and ill. - New York March 8–May 27, 2001

Vermeer and the Delft School

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

no. 78 - London June 20–September 16, 2001

Vermeer and the Delft School

National Gallery

no. 78 - Madrid February 19–May 18, 2003

Vermeer y el interior holandés

Museo Nacional del Prado

184–185, no. 40 and ill. - Newcastle upon Tyne 19 April–13 July, 2008

Love is in the Air

Laing Art Gallery

no catalogue - Rome September 27, 2012–January 20, 2013

Vermeer. Il secolo d'oro dell'arte olandese

Scuderie del Quirinale

224, no. 51 and ill. - London June 26–September 8, 2013

Vermeer and Music: Love and Leisure in the Dutch Golden Age

National Gallery of Art

65, no. 22 and ill. - Dresden March 19–June 27, 2021

Vermeer: Johannes Vermeer's Dresden Girl Reading a Letter at the Open Window and Dutch Genre Painting from the 17th Century

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden - Amsterdam February 10– June 4, 2023

VERMEER

Rijksmuseum

no. 33 and ill.

(Click here to access a complete, sortable list of the exhibitions of Vermeer's paintings).

A pendant?

Not all critics agree that the present painting and the Lady Seated at a Virginal were conceived as a pendant although following Walter Liedtke's reasoning, the National Gallery in London has equipped them with identical frames.

There seems to exist much more evidence that joins the two works than separates them. In favor of the pendant hypothesis, firstly, are their near-identical dimensions. The two young women play music on a finely crafted virginal decorated with faux marble side panels. Both figures perform in the right-hand corner of a room and are dressed in stylish clothing of the day. Both turn to look at the viewer. Both rooms exhibit fine marble flooring with diagonally set black and white slabs. A picture-within-a-picture hangs on the background wall as a visual comment on the scene below.

Obviously, the pendant format does not imply identical treatment of a given motif. In fact, Dutch painters relished the opportunity to reveal opposing qualities of the same subject. Many facts suggest that they represent opposite aspects of a single concept, such as Sacred and Profane Love.

The overall atmosphere and compositional dynamics of each work are markedly different. The standing woman plays erect, her pose recalling the perfection of a classical column, bathed in sunlight which floods the room through an open window. Oppositely the seated woman crouches ever-so-hesitantly over her virginal, shrouded in near obscurity. The blue curtain catches whatever light might have leaked through the closed shutters of the window.

Key indicators of the opposing forms of love are the background pictures. The heads of both paintings occupy the extreme corner of each large-scale painting which reminds the modern viewer of today's cartoon speech balloons. The painting of the Cupid, encased in its austere rectangular frame, is generally interpreted in the light of a 17th-century emblem from Otto van Veen's Amorum Emblemata, advising that one must have only one lover (in Van Veen's version, the Cupid holds aloft a card with a Roman numeral I while in Vermeer's version, the same card is mysteriously empty).

In the other work, a low-life bordello scene painted by the Utrecht artist Dirck van Baburen in a gaudily gilt frame suggests, as Walter Liedtke wryly observes, "something more like one love an hour than one for life." Liedtke further posits that while the seated lady is certainly not a prostitute, her attitude about amorous affairs is illustrated by her relaxed demeanor and the "Arcadian landscape—the easy path—painted on the virginal lid." Her standing counterpart may have chosen the steep and rocky but virtuous road (chosen by Hercules) of the landscape lid.

In Dutch 17th-century painting, the most common subjects for pendants were the five senses and the four seasons which were repeated in endless variations. Portraits of husband and wife were equally created as a pendant, although the portrait category was the most conservative of all and left relatively little latitude for experimentation even in the hands of the most competent masters like Rembrandt or Frans Hals.

Amorum Emblemata & the emblem book

Amorum Emblemata

"Perfectus amor non est nisi ad unum"

Otto van Veen

1608

Engraving, Antwerp

The 1531 publication of the first emblem book ever to be published (Emblematum liber), by the Italian jurist Andrea Alciato, launched a literary fashion that would last two centuries and touch most of western Europe. The two 1608 editions of Amorum emblemata were followed by a third in 1659. Emblem books were crucial in shaping the visual and verbal culture of the 17th-century Dutchmen. Professional painters collaborated with the authors of emblem books to produce drawings from which the illustrations could be engraved. Art historians believe that Vermeer occasionally consulted emblem books to refine the narratives of his works.

An emblem is a riddle composed of three parts—a "lemma" or motto, a picture and a following explanatory text, intended to draw the reader into a self-reflective examination of his or her own life in an interesting manner. More complicated associations of emblems could transmit information to the culturally informed. However, the aim of the emblem was to make morality more attractive although emblematic art.

"Silence"

Andrea Alciato

Emblematum liber

Emblem 11

Emblem books were published in vast quantities. Alciato's Emblematum liber was reprinted 49 times, and 90 translations and adaptations all over Europe. Their popularity is often thought to reflect the 17th-century mindset with its tendency to think in analogies and allegories.

From c. 1600 onward, love emblems, mainly Petrarchist in tone and content, were particularly successful in the Netherlands. Typical emblems were half-moralizing and half-playful. The perspective of the male lover is dominant, although his role is that of an ecstatic victim.

Many emblem books were intended for the "courting youth," young men and women in search of a spouse, a topic which obviously made them fecund resources for interior painters who explore ritualized, burger courtship and love letter motifs. Some contained both emblems and songs. Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft's Emblemata amatoria is one example (with 71 pages devoted to emblems and 73 to songs and sonnets).

Eddy de Jongh has shown the major influence of the emblem on Dutch 17th-century painting, and recently the impact of the love emblem on occasional poetry has been demonstrated by P. van Huisstede en H. Brandhorst. The resulting insights into textual and pictorial symbols shared between different art forms make comparative emblem studies useful to scholars in a number of disciplines. Besides this, studying the emblematic tradition provides us with knowledge about concealed aspects of the cultural and mental history of the period.

m: Dutch Love Emblems of the Seventeenth Century http://emblems.let.uu.nl/project_project_info.htmlVermeer's "love affair" with Cupid

Cupid Preparing His Bow

Jacob Huysmans after Anthony van Dyck

between 1650–1696

Oil on canvas,

Private collection

Cupid, known as Eros in ancient Greek mythology, is the god of desire, erotic love, attraction, and affection. He has been a favorite subject of artists since ancient times. The motif of Cupid was popularly used in Baroque painting, either by itself or in various mythological scenes. In Vermeer's paintings, he appears—either partially or fully—four times as a picture-within-a-picture.

Cupid Holding a Glass Orb

Caesar van Everdingen

c. 1655–1660

Oil on canvas,

Private collection

As has often been noted in Vermeer literature, "a Cupid" could mean either a statue or a painting of the winged god of love. The painting that Vermeer used as a model was first attributed by German art historian Gustav Delbanco in 1928 to Caesar van Everdingen, a Dutch Golden Age portrait and history painter who painted numerous depictions of similarly proportioned naked putti (nude child figures, often with wings). Based on the chronology of Vermeer’s paintings, the inclusion of the same Cupid four times, albeit with slight variations, over a 15-year period makes it highly probably that Vermeer had this work in his home. This is reinforced by the fact that the probate inventory of Vermeer’s estate, compiled in 1676, two months after his death, mentions an artifact "from the upstairs backroom" referred to as "Cupid," which could be this painting.

Art historians have tried to track Vermeer's Cupid in the vast history of auctions and sales of art, but it has proved impossible to find. Interestingly, based on Vermeer canvases, they tried to estimate the size of the real Cupid painting – it should be approximately 115 x 85 cm, which is quite large.

Another question is: what did Vermeer wish to convey with the now-lost Cupid? Did its meaning change according to its context? Numerous art historians and Vermeer experts such as Walter Liedtke, Aurthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Gregor Weber have attemtped furnish plausable explanations. However, as Weber pointed out, the exact meaning Vermeer intended may be elusive, but the deliberate alterations in how he portrayed the Cupid across different works were likely intended to give a more nuanced meaning to the scene unfolding in the foreground. Perhaps this kind of puzzle would have delighted a 17th-century audience familiar with the similar emblematic images that abounded in emblematic literature.

In A Maid Asleep, although barely visible in reproductions, Cupid strides forth "triumphantly," trampling over two masks cast upon the ground. Perhpas the cause of the "dozing" (tipsy?) maid's condition is in fact, Cupid's working.

Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window

Johannes Vermeer

In the Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, Cupid tramples on a mask, a motif not seen in the Late Lady Standing at a Virginal. Here, the mask is a readily understood metaphor for deceit. In other words, in matters of the heart, Cupid rejects deceit in favor of sincerity.

In the Girl Interrupted in Her Music, the inclusion of the standing, nude god of love underscores the amorous nature of the encounter between the lady and her company. Because it was overpainted in the past and subsequently restored, the paint layer of Cupid is severely abraded. Originally, it would have been easier to discern how Cupid seems to comment on the man’s seductive wiles from behind the latter’s back. Both the woman and Cupid peer at the viewer, drawing them directly into Vermeer’s painted scene.

A Lady Standing at a Virginal

Johannes Vermeer

In the last depiction, in Lady Standing at a Virginal, Cupid is pictured standing, rendered in lighter, airier tones than in the preceding versions. He holds a blank card, reminiscent of the Cupid in another emblem from Otto van Veen’s popular "Amorum emblemata." However, there, Cupid holds a tablet inscribed with the number "1." Meanwhile, with his foot, he tramples on the numbers 2 to 10 on another tablet. The caption explains that true love can be directed to "one person alone." Strangely, no mask appears at his feet in Vermeer's work.

Scholars have been unable to explain precisely why Vermeer would have included the Cupid so frequently in his own works, especially considering he must have had many other works to choose from that he traded, like many artists of the time, to supplement his income.

Whatever the Vermeer's intentions, the painted Cupid belongs to the pictorial tradition of portraying a full-figure, life-size Cupid alone, combined with symbolic gestures and motifs. Other great painters from this time, such as Rembrandt, who painted Cupid blowing a bubble in 1634, popularized this motif. The little god of love was also often presented with a golden balance, a pair of scales, and, of course, wings.

The final hardships of Vermeer's life

Critics have frequently underlined that Vermeer's late works fail to show even the vaguest trace of the years of disaster that tormented the Dutch Republic, whose long run with good luck finally came to an end. In 1672, Louis XIV overran the lowlands, sending waves of shock throughout the country. The Dutch defense had been poorly organized, and some towns capitulated without firing a shot. In Vermeer's hometown Delft, the citizens rioted. To impede the advance of the French troops, large areas of the countryside were flooded, as had been done against the Spanish years before. This year had been named rampjaar or "year of disaster."

Fortunately, the city walls of Delft were never attacked, although Vermeer's household, with numerous children to support, was severely tested by the collapse of the art market. His wife would later testify that the artist had hardly earned anything from his own work and that he was forced to sell the works of other artists in which he dealt in at a great loss. He may have painted very little in his final years, distracted by his service in the civic guards and his own bad health.

The tiny signature

Vermeer's characteristic monogram was carefully painted with light-toned pigment on the shadowed side of the virginal, as indicated above. However, it cannot usually be distinguished in reproductions.

Of the 35 generally accepted paintings by Vermeer, 25 bear signatures, which, however, vary greatly in state of conservation and, hence, visibility. Four signatures that were once reported can no longer be detected,1 and three paintings once bore the signatures of other artists before they were correctly attributed to Vermeer. Only three signatures are accompanied by dates.3 One painting bears two signatures, one of which is accompanied by a date. Never once did Vermeer accompany a signature with "f[ecit]," a frequent feature that accompanies signatures on numerous Dutch paintings of the period.

Vermeer's signatures are located on almost every area of the canvas. Some signatures float upon a blank area of a white-washed wall or a dark void. Others are positioned deliberately on simple objects, such as a footstool, a picture frame, or a rock, without seeking, except in one or two cases, symbolic or physical identity with the underlying object. Nine are inscribed on patches of bare white-washed wall. A few signatures were once so conspicuous that they may have been intended to contribute to the aesthetics of the work.

A neglected Cupid?

Such is the power of Vermeer's work that each detail, no matter how minute, has been subjected to intense scrutiny by art historians. Like no other artist, he seems to have possessed an almost magical power that allowed him to imbue the breath of humanity in even the insignificant object of his compositions.

The art historian H. Rodney Nevitt singled out the small Delft wall tile to the left of the standing musician's satin gown and has identified it as a fishing Cupid. Such motifs were frequently drawn from popular literary sources. The present Cupid is similar to the fishing Cupid in a print from Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft's Emblemata amatoria which plays on the conventional comparison of courtship to fishing. In Vermeer's tile, the fishing rod is visible, the proportions of the figure are consistent with Cupid, and the dark shape on his back can only be his stubby wings. No doubt, contemporary viewers would have been familiar with such designs on their own walls and would have responded to the Cupid in Vermeer's tile. They may have been amused by the close proximity of Cupid who seems to arouse with a discreet poke the austerely posed lady rather than keeping his mind to his fishing.

illustration from

Pieter Cornelisz. Hooft, Emblemata amatoria

Amsterdam, 1611,

Koninklijke Bibliotheek The Hague

The theme of love seems to concur with the presence of the virginal. One vryerijboek (manual for young lovers) advises young women: "Learn ...to steal hearts / With Clavecimbel-playing."

Considering the confrontational gaze of the lady and the large-scale painting of a Cupid on the background wall, Nevitt, therefore, submits that Vermeer's A Lady Standing at a Virginal "fishes for us, we fish for her, or Cupid fishes for us both."

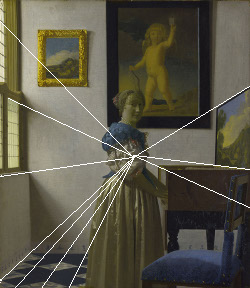

Meaning in perspective

Without a doubt, A Lady Standing at a Virginal presents the most schematic perspective in Vermeer's oeuvre, in some respects recalling the hollow box-like spaces commonly illustrated in period perspective manuals. In no other work did Vermeer employ linear perspective to control the viewer's attention so explicitly. Coupled with the rigorous recession of the floor tiles, the orthogonals—both to the left and right of the stately figure—draw the spectator into a vibrating but mathematically measured space where they are urged to come to terms with the solitary figure of the musician, set in the dead center of the picture.

On the contrary, the space of A Lady Seated at a Virginal remains comparatively flat, despite the strong orthogonals of the virginal. The perspective, while accurate from a technical point of view, is not as functional to the composition as that of its pendant, A Lady Standing. This is largely because the vanishing point is set behind the figure's shoulder, perhaps too far to the right, creating a large open space that divides the figure from her instrument. In comparison, note how the figure and the virginal of A Lady Standing are sensed as a single, tightly bonded entity.

In 1435/1436, Leon Battista Alberti wrote De pictura (On Painting), a treatise on proper methods of showing distance in painting in which the basis of linear perspective was codified for the first time. Alberti's breakthrough not only made it possible to construct the illusion of coherent three-dimensional spaces in painting but also to requalify the art of painting, which had been relegated to the mechanical arts from classical times.

The practice of perspective was still highly esteemed in Vermeer's time. One of the few instances his name was mentioned in contemporary writing, he was noted for his skill in perspective.

Listen to period music

![]() Almande De Symmerman [236 KB] very likely Almande The Carpenter (anon.) from The Susanne van Soldt Manuscript (1599)

Almande De Symmerman [236 KB] very likely Almande The Carpenter (anon.) from The Susanne van Soldt Manuscript (1599)

![]() Malle Symen [236 KB] "Silly Simon"

Malle Symen [236 KB] "Silly Simon"

(Jan Pzn. Sweelinck) from The Leningrad Manuscript (1646)

![]() Courante Daphne [236 KB] The popular melody Daphne as a French "Courante" dance (anon.) also from The Leningrad Manuscript (1646)

Courante Daphne [236 KB] The popular melody Daphne as a French "Courante" dance (anon.) also from The Leningrad Manuscript (1646)

* all three music files were kindly selected and performed for the Essential Vermeer website by Joop Klaassen, contributor to the Stichting Clavecimbel Genootschap Nederland.

The Virginal

The virginal (or virginals), together with the harpsichord, has its origin probably in the medieval psaltery with a keyboard applied for playing polyphonic music (i.e. melody with accompanying chords). In c. 1460, the virginal is mentioned for the first time in a treatise by Paulus Paulirinus of Prague. Although limited in its tonal resources, the virginal occupied a crucial position in the musical life in the 16th and 17th centuries because it was smaller, simpler, and cheaper to make than the harpsichord, rarely represented in paintings.

The main center of virginal- and keyboard production was undoubtedly Antwerp, with the renowned Ruckers and Couchet families. Italy was the second most important center. After King Henry VIII purchased five virginals, it enjoyed considerable appreciation in England as well. Until the 18th century, the virginal remained in use both as a solo instrument (even in private circles) as well as for accompaniment of the singing voice or melodic instruments, like the viola da gamba.

The virginal normally had a rectangular case, although polygon forms in various sizes were also built. The metal strings, only in a single choir, run roughly parallel to the keyboard. They are plucked by plectra mounted on jacks. The jacks (one for each key) are arranged in pairs and placed along the line running from the front of the instrument at the left to the back at the right. They pluck in opposite directions so that the pairs of jacks are separated by closely spaced pairs of strings. Each pair of jacks is usually served by a single slot in the soundboard, together with another slot below in a thin guide above the keys. Leather on the soundboard and lower guide provide a quiet bearing-surface for the jacks.

The typical Flemish "muselar" type (probably invented by Hans Ruckers) has the keyboard to the right side, their strings plucked at a point near the center for virtually their entire range, producing a powerful, flute-like tone. Since the jacks and keys for the left hand are inevitably placed in the middle of the instrument's soundboard, mechanical noise from these is amplified. The central plucking point in the bass strings makes repetition difficult because the still-sounding motion of the string interferes with the ability of the plectrum to connect again. Thus, the muselaer is better suited to chord and melody music without complex bass parts.

The spinet virginal has its keyboard placed off-center to the left. The jacks run in a line close to the left-hand bridge; therefore, the point at which the jacks pluck the strings is close to the mid-point in the treble and well away towards the left end in the bass. Thus the timbre of the spinet gradually changes from flute-like in the treble to reedy in the bass.

Double shadows

One of the most curious features of Vermeer's rendering of light is the double shadow. Double shadows are caused by the overlap of two shadows cast by light entering the room through two different windows. The first time they appear in Vermeer's oeuvre is in The Music Lesson where they are plainly visible to the right of the hanging mirror and to the right of the erect virginal lid. Double shadows rarely appear in the works of other artists. Painters were recommended to eliminate them lest they confuse the viewer. However, Vermeer did not adhere blindly to the reality he observed but utilized its most distinguishing aspects to exalt the pictorial and thematic reality of the work at hand. One scholar has noted that compared to the shadows generated by a scale reproduction of the room represented in The Music Lesson, the shadows in Vermeer's painting are notably narrower.

The double shadows in the present work are more clearly defined than those in The Music Lesson, which could be caused either by greater intensity of light or by stylistic considerations. They appear on the right-hand side of the gilt frame and the large ebony framed Cupid. P. T. A. Swillens, who first noted double shadows in his monographic study of 1950, included a diagram which illustrates how the longest shadows are cast by light entering through the window farther from the viewer (the one nearly attached to the background wall) while the second is cast by a second window nearer to the viewer. This second window appears in The Music Lesson but is only implied by the double shadows in A Lady Standing at a Virginal.

In Dutch painting, double shadows were avoided as much as possible because they were thought to create compositions that seem restless and confused. It is an evil against which the art experts of Vermeer’s time and later were always warning artists. Van Hoogstraten writes about this in his Inleyding tot de hooge Schoole der Schilderkonst and De Lairesse devotes a whole chapter to "Van de lichten binnenskamers" (Of Indoor Lighting), which he illustrates with a few examples." Other than those of Vermeer, one of the very few careful portrayals of double shadows in Dutch interior painting can be found in Gabriel Metsu’s A Man and a Woman Seated by a Virginal (c. 1665), which, however, is an emulative composite of certain aspects of Vermeer’s The Music Lesson and The Concert.

The miracle of satin painting in 17th-century

The ability to convincingly depict the different textures of drapery was a major requisite for painters who wished to appeal to the upper tiers of art lovers. And nowhere else than in the Netherlands had satin-painting been so successful-

The Music Lesson

Jacob Ochtervelt

c. 1660–1662

Oil on canvas, 97.1 x 78.1 cm.

City Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham

Painters like Pieter Codde and Willem Duyster were among the first to capture the distinct feel of satin with paint and brush, which gave them an incremental advantage over their most competitive peers. However, no one has ever surpassed Gerrit ter Borch in this field, and a significant portion of his immense popularity was based on this skill. No one before or since has ever succeeded in capturing the nuances of satin so convincingly. Some of his renditions of the long satin gowns were evidently so in demand that he painted the same gowns on multiple occasions—one seven times—from the exact same point of view, with the same lighting and folds. Each time, he set it in a different context so that each work would be appreciated as an original piece of art, rather than as a copy. Only in the work of Jacob Ochtervelt, a minor Dutch painter who was aware of Vermeer's presence on the art scene, do we find faint signs of Ter Borch's almost monstrous talent for rendering this precious material.

So when Vermeer included this kind of luxurious garment in his painting, he was well aware that it would be compared to those of the most highly appraised and sought-after painters of the moment.

How did painters learn to paint satin so convincingly? Most artists started their careers as apprentices in the studios of established painters. Here, they learned the basics of painting, including how to mix pigments, prepare panels and canvases and copy masterworks. Over time, they would practice by rendering objects with challenging textures, such as satin.

Painting luxurious fabrics was particularly difficult and time-consuming. Because the folds change with the movement of the body, and painters could not usually finish them in a single session, life-size wooden manikins were dressed with the sitter's most costly clothes. The accurate portrayal of satin relies heavily on understanding how light interacts with the material. Satin's sheen is complex, with soft gradients and sharp highlights. Dutch artists like Vermeer were particularly skilled in capturing how light behaves, and this understanding was essential for rendering the unique way satin reflects light.