On the evening of September 23, 1971, a twenty-one year old hotel waiter, Mario Pierre Roymans, stole Vermeer's Love Letter from the Palace of Fine Arts in Brussels where it was on loan from the Rijksmuseum as a part of the Rembrandt and his Age exhibition."Rembrandt en zijn tijd," Paleis voor Schone Kunsten, Brussels, September 23 - November 21, 1971.

Roymans locked himself in an electrical box in the exhibition hall and, once the museum was closed, he pulled the painting from the wall and made for a window. When the frame was too large to go through the window and because he was unable to extract the canvas quickly from the frame, he clumsily slashed the painting out of its frame with a potato peeler. He then tucked the painting into the back of his trousers where it sustained even further damage. At first, Roymans hid the canvas in his room; later, he buried it in the forest. When it had begun to rain, he dug the painting up and put it in a pillowcase, hiding it under the bed mattress of his hotel room in the café-restaurant of the Soetewey Hotel where he worked.

Roymans conceived his plan after he had seen television images of the humanitarian disaster in East Pakistan, probably the first time that viewers were confronted with such a humanitarian disaster. The 1971 Bangladesh genocide involved bloodshed and human rights abuses in East Pakistan during the Bangladesh Liberation War. Massacres, killings, rape, arson, and systematic elimination of religious minorities (particularly Hindus), political dissidents and the members of the liberation forces of Bangladesh were conducted by the Pakistan Army with support from paramilitary militias. The idealist waiter from Limburg, Belgium felt that something had to be done for the victims of the disaster.

The robbery became world news, and a massive hunt for the precious work ensued.

On the night of 3–4 October, Roymans, who called himself "Tijl van Limburg," after a legendary hero who helped the poor, Robin-Hood style,Tijl van Limburg, also known as "Tijl Uilenspiegel" in Flemish folklore, is a legendary figure often associated with stories of wit, cunning, and rebelliousness. His character, which dates back to medieval times, has become a symbol of resistance against oppressive authorities and a champion of the common people. The tales of Tijl van Limburg are similar to those of other trickster heroes like Germany's Till Eulenspiegel or England's Robin Hood. These stories typically involve clever pranks or acts of defiance against the ruling class or ecclesiastical authorities, often highlighting the character's intelligence and resourcefulness. Over time, Tijl van Limburg has been portrayed in various forms, including literature, theater, and even political commentary, embodying the spirit of freedom and resistance. His character has evolved to reflect the changing social and political contexts in which his stories are told, serving as both a source of entertainment and a symbol of rebellion against tyranny or injustice. during the Spanish Inquisition, contacted a reporter from the Brussels newspaper Le Soir and arranged a predawn meeting in a pine forest near Zolder (Limburg, Belgium). On the cold, foggy early morning, the reporter waited for Roymans in his car. As instructed, he had brought his camera along. After a half hour, Roymans, medium height and thin, appeared out of nowhere and greeted the reporter with his face covered by a plastic mask. He opened the door of the car, pushed the reporter over to the passenger's side, sat behind the wheel and instructed the reporter to put on a blindfold. Roymans drove for a half hour through the pre-dawn fog and parked the car in front of a small church. Getting out, Roymans told the reporter to wait. Soon after, Roymans returned with the painting wrapped in a white cloth. He allowed the reporter to take about ten photographs by the car headlights to prove he actually had the painting. The reporter was again blindfolded, and while driving back, Roymans, who by this time seemed to have relaxed considerably, began to talk freely. He confessed that he loved art and would have given ten years of his life to keep the painting but knew he couldn't. He said he also loved humanity and felt he had to do something to alleviate human suffering.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1667–1670

Oil on canvas, 44 x 38.5.cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

A photograph of the painting was published along with Roymans' three conditions for the painting's return: (1) that 200 million Belgian francs be given to Bengali refugees in East Pakistan who had been suffering desperate famine, (2) the Rijksmuseum should organize a campaign in the Netherlands to raise money to combat world famine, and (3) the Palace of Fine Arts in Brussels should do the same in Belgium. Roymans set the deadline for Wednesday, 6 October.

The morning after publication, the police arrived at the Le Soir headquarters demanding an explanation for why they had not been contacted before the meeting with Roymans. The police confiscated the photographs and secured the help of art experts to examine them to determine if they represented the real painting. It was determined that they were, indeed, photos of the cherished Love Letter. Adding to the tension of the moment, Dr. A.E.F van Schendel, director of the Rijksmuseum, released a public statement saying that the Le Soir photographs were not sufficient to prove it was the original painting and not a reproduction. Anxiety mounted as in the days that followed, Roymans made many other phone calls to newspapers and radio stations.

According to the Dutch art historian and Vermeer expert Albert Blankert, Roymans' demands were "alarmingly well received" by the Dutch public. Petitions were circulated urging authorities to rescind the warrant for his arrest and there were spontaneous initiatives in favor of the refugees from East Pakistan. A wave of sympathy spread across the country, and slogans in favor of Royman's cause were seen chalked on bridges and walls.

Although it would seem that an innocent work of art never could become caught in an unrelated political crisis, Robert Jones, the head of the Belgian Museum, said he believed that the waves of thefts that had recently hit European art museumsIn the year of the Love Letter theft, fifteen valuable paintings were stolen from the home of Peggy Guggenheim in Venice and a Titian was stolen from a church. had been encouraged by publicity given to the high prices fetched by important works of art. This then made the works of Vermeer prime targets for crimes of any kind.

Roymans telephoned the Belgium newspaper Het Voljk saying that unless a contract meeting the ransom demands were signed on a live television broadcast, he would sell the painting to an anonymous American art collector. Insurance experts said it would be virtually impossible to arrange a televised ransom agreement by the deadline fixed by Roymans.

Finally, on October 6, the deadline day of his demands, Roymans was arrested in eastern Belgium soon after he made a telephone call to the Belgian newspaper from a public telephone at a BP service station. Annie Mommens, the wife of a service station owner, overheard Roymans' call, and as Roymans rode off on his motorcycle, telephoned the police while Mr. Mommens gave chase in his car. According to Mr. Mommens, when Roymans saw him meeting the police along the road, "he panicked, jumped off his motorcycle and ran across a field towards a farm. He hid in a cowshed underneath the straw. That's where I grabbed him." Roymans was hiding between two cows. The two-week ordeal was over.

Roymans immediately led the police to his room where he kept the painting.

Mark Durwael, the son of the owner of the Soetewey Hotel where Roymans stayed, described Roymans as "a neat, courteous and a good worker." "But he had a passion for Pakistan. Every time work slacked off he began talking about the sad plight of the Bengali refugees." Durwael said that Roymans followed the case of art theft closely, "When the news began, he always slipped away." After his arrest, the Limburg Robin Hood had more than ever the public on his side. Newspapers and radios received many letters and messages in his support.

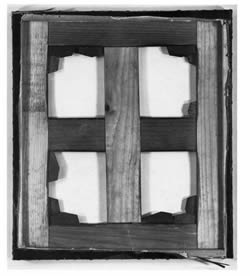

The front side of the damaged Love Letter

The Love Letter was delivered to the Rijksmuseum on 8 October and was shown to the press on 11 October. Since the painting had been seriously damaged, an international committee was formed to oversee the restoration. The committee decided to restore the lost and damaged parts as faithfully as possible in order to maintain the painting's accentuated illusionist quality even though some Dutch artists felt the canvas should be left in the damaged state. The heist lasted short of two weeks. The restoration lasted almost an entire year.

The painting was put on exhibition from December 28 until January 7, 1973 in the Rijksmuseum Room No. 230 (the Gallery of Honour). Alongside it were shown about thirty photographs of the work in order to give the public an idea of how the painting was restored. Some lamented that the restored areas of the foreground doorway looked too flat.

Roymans was brought to trial on 20 December and sentenced on 12 January by the Brussels court to a fine and two years in jail although he served only six months. After his release, he married and had a child. He suffered from severe depression, and his marriage failed. He began living in a car and on Boxing Day, 1978, he was found sick in his car along a road near Liege gravely ill. Ten days later, on January 5, 1979, he died at the age of twenty-nine. Although Roymans had been a hero for many, he brought much sadness to his family. According to his older sister, he was an idealist far ahead of his time. At the time of the theft, police said Roymans' father was dead and his mother was living in Spain. According to Sue Sommers, who wrote a book on Roymans, Roymans had severe mental problems and had wanted to steal Leonardo's Mona Lisa.

Roymans was born in from Tongeren, Belgium and is buried in the old cemetery of Nerem (Tongeren), the ninth tomb in the eleventh row. After his arrest, Mario Roymans faced a downward spiral in his life. The judge, recognizing Roymans' naivete, sentenced him to twenty-four months in prison, but he only served a part of this term. Despite this leniency, and the public's sympathy and support for his actions, Roymans fell into a deep depression. A few years later, he was found in a field, barely alive. The cause of his death remains a subject of speculation, with filmmaker Stijn Meuris, a musician and film director Stijn Meuris who had long been fascinated by the story of Roymans, suggesting that it was not suicide but rather a result of his misery. Following his release, Roymans openly expressed his profound disappointment over his inability to help the people in Bangladesh, which had been his initial intention., made an empathetic documentary of the case.

† FOOTNOTES †

Thefts, forgeries & the Van Meegeren case

The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van Meegeren

The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van MeegerenJonathan Lopez

2009

The Forger's Spell: A True Story of Vermeer, Nazis, and the Greatest Art Hoax of the Twentieth Century

The Forger's Spell: A True Story of Vermeer, Nazis, and the Greatest Art Hoax of the Twentieth CenturyEdward Dolnick

2009