Saint Praxedis

(questionable, attributed to Vermeer)1655

Oil on canvas, 101.6 x 82.6 cm. (40 x 32 1/2 in.)

Kufu Company Inc., on long-term loan to the National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo

collection number: DEP.2014-0001

The textual material contained in the Essential Vermeer Interactive Catalogue would fill a hefty-sized book, and is enhanced by more than 1,000 corollary images. In order to use the catalogue most advantageously:

1. Scroll your mouse over the painting to a point of particular interest. Relative information and images will slide into the box located to the right of the painting. To fix and scroll the slide-in information, single click on area of interest. To release the slide-in information, single-click the "dismiss" buttton and continue exploring.

2. To access Special Topics and Fact Sheet information and accessory images, single-click any list item. To release slide-in information, click on any list item and continue exploring.

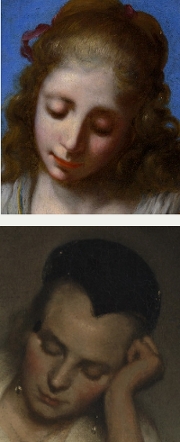

The young saint's face

Those who support Vermeer's authorship of Saint Praxedis frequently point out the similarities between the saint's physiognomy and that of the dozing girl in A Maid Asleep (see right; the detail of A Maid Asleep has been reversed to facilitate comparison). According to Vermeer expert Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., the brushwork, paint structure and buildup of the heads are analogous.

In any case, the young Vermeer seems to have already revealed his lifelong fascination for female interiority in his early history paintings. Although Diana and her Companions and Christ in the House of Martha and Mary represent themes of great historical importance, we sense that the artist's interest lies as much in the women as individuals as in the protagonists of some impending narrative.

With respect to the original, the modeling in Vermeer's copy is more accentuated, making Ficherelli's face appear the sweeter of the two; the head in Vermeer's version seems slightly elongated.

Examining Vermeer's early history paintings yields intriguing observations about his artistic trajectory. Notably, these works, such as Diana and Her Companions and Christ in the House of Martha and Mary and the Saint Praxedis, demonstrate an early inclination to focus on the inner worlds of his female subjects. This thematic interest distinguishes him from many of his contemporary genre painters and may serve as a precursor to the deeper emotional undertones that come to define his later works.

As the art historian Tico Seifert observed, Vermeer's close ties with the Delft Jesuits have long been recognized but have recently been described in much greater detail, creating an even more plausible context—individually and historically—for this painting within Vermeer's life and oeuvre. A devotional painting such as Saint Praxedis fits well with Vermeer's presumed conversion to Catholicism shortly before his marriage in 1653, and with his links to the Delft Jesuits. The saint and the prominence of the crucifix in particular—which Vermeer added to Ficherelli's composition—both align well with the Jesuit order and their intense veneration of Christ on the cross. Whether Saint Praxedis was a Jesuit commission remains speculative.

The blue sky

The intense blue sky was painted according to Italian practice. A mixture of natural ultramarine, a pigment made of the powder of crushed lapis lazuli, imported from Afghanistan, and lead white was painted over a warm brown imprimatura. This technique creates an unusual depth, analogous to the depth of the sky itself.

Natural ultramarine, the rarest and costliest pigment of the 17th century, became the most characteristic pigment on Vermeer's otherwise conventional palette. It has been hypothesized that, owing to its elevated price, Vermeer's patrons Pieter van Ruijven and Maria de Knuijt supplied it to the painter to guarantee the exceptional brilliance that only ultramarine can produce.

The colors in Vermeer's copy appear more saturated than those in Ficherelli's original.

The golden crucifix

Allegory of Faith (detail)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1674

Oil on canvas, 114.3 x 88.9 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

One of the most significant differences between Vermeer's copy and Ficherelli's original Saint Praxedis is the inclusion of a crucifix in the hands of the kneeling Saint. Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., the initial proponents of the painting's attribution, believes that it may reflect the young artist's newfound Catholic sympathies, as it is generally believed that Vermeer converted to the Catholic religion two years earlier upon his marriage to Catharina Bolnes.

John Michael Montias, Vermeer's chief biographer, speculated that the Jesuits might have commissioned the young Delft artist to make a copy of the painting. "It was perhaps even they who instructed Vermeer to put a golden crucifix in the hands of the Saint: for a crucifix in 17th-century Holland was the symbolic object, that above all objects, signaled its owner's adherence to the Roman Catholic faith." Montias also points out that Saint Praxedis reflects Vermeer's early concern with women, even in his early history paintings.

The crucifix held particular importance among Catholics families. To instill piety and keep impure thoughts at bay, a crucifix often hung in the corner of the room containing the marital bed, as well as a painting of the Virgin Mary near the head of the bed. In Vermeer's house, both such objects were listed in the probate inventory after the artist's death. "An ebony crucifix" and "a painting representing the Mother of Christ" were listed in the groote zael (Great Hall). Vermeer himself painted an ebony-veneered crucifix bearing the body of Christ in Allegory of Faith, perhaps a 17th-century crucifix from Augsburg, where similar gilded bronze crucifixes with an ebony cross were common.

The use of ebony for Vermeer's crucifix also suggests a desire to use high-quality materials for items of spiritual significance. This is reflective not only of Vermeer's personal faith but perhaps also of a broader trend among Catholics of his time to adorn their worship spaces and homes with objects crafted from valuable materials.

This approach is deeply rooted in the Church's history and theology. According to Catholic belief, devotional objects are not merely symbolic but are involved in the sacramental life of the Church, often becoming "conduits" of divine grace. Hence, the higher the quality of the materials, the more fitting they are considered for divine worship.

On the other hand, Protestant views on this matter are varied but generally more austere, influenced by the principles of the Reformation that rejected what was seen as the excesses and "idolatries" of the Catholic Church. Leaders like Martin Luther and John Calvin advocated for a simpler approach to religious worship, devoid of what they considered ostentation or extravagance. The Protestant ethos generally leans towards the belief that one's personal relationship with God does not require elaborate objects of veneration and that such items could distract from the true essence of faith.

Who was Saint Praxedis?

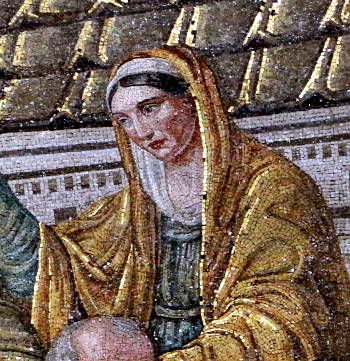

Saint Prudenita in a mosaic in the

basilica of Santa Pudenziana in Rome

Saint Praxedis, or Prassede, was a Roman Christian of the second century who is chiefly noted for having cared for the bodies of those martyred for their faith. Scriptures relate that 23 Christians were discovered in the home of Saint Praxedis; they were martyred before her very eyes. She had the presence of mind to collect their blood with a sponge and place it in a well, where she herself was later buried, marked by the disk in the Basilica's floor. The sponge of Saint Praxedis was preserved as a relic in the Roman church dedicated to the Saint.

Her name is often associated with her sister, Saint Pudentiana, who may appear in the right background of Vermeer's painting, walking near the martyrium. Both are followed by their father, Pudens, a disciple of Saint Paul. However, while there is existing evidence for the life of Saint Pudens, there is no direct evidence for either Praxedis or Pudentiana. It has been suggested that there was no such person as Pudentiana; the name may have originated as an adjective for the titulus of Pudens and was mistaken for the name of a female by later generations.

After many years of burying mutilated Christians, visiting the imprisoned and comforting suffering loved ones, Praxedis died on July 21 of a disputed year. This date is now her feast day on the Roman Catholic Church calendar. Her remains are presumably housed in a vault in the Basilica of Saint Praxedis, in the center of Rome. The Basilica, built atop the remains of 4th-century ancient Roman Thermae privately owned by the family of Pudentiana and called Terme di Novato, incorporates mosaic decoration that marks it among the oldest churches in Rome. It was successively enlarged and decorated by Pope Paschal I around 822.

A beheaded man & a blood-filled sponge

In Vermeer's picture, a beheaded man lies to the right-hand side of Saint Praxedis, who squeezes out a blood-filled sponge. She had gathered the martyr's blood with this sponge. The figure of the martyr is painted with greater emphasis than in the original work by Ficherelli. he story of the sponge is not included in the Legenda aurea, the standard work on the lives of the saints, but it is found in Het leven der HH. Maeghden, by Heribert Rosweyde, a Jesuit hagiographer.

The present-day Basilica of Santa Prassede in Rome is said to contain the sponge of Saint Praxedis—not to be confused with the Holy Sponge of Christ—which she used to collect the blood of 23 Christian martyrs who had been murdered before her very eyes. Saint Praxedis had placed the sponge in a well, where she herself was later buried.

Vitae patrum

Heribert Rosweyde

1615

In Christianity, relics are the material remains of a deceased saint or martyr, as well as objects closely associated with those remains. Relics can be entire skeletons, but they more commonly consist of a part, such as a bone, hair or tooth. A piece of clothing worn by the deceased saint or even an object that has come in contact with a relic is also considered a relic.

As the lives of the martyrs became an important source of inspiration for Christian worshippers, their lives and relics became revered. The second-century Church Father Tertullian wrote that "the blood of martyrs is the seed of the Catholic Church," implying that the martyrs' willing sacrifice of their lives leads to the conversion of others. Many tales of miracles and other marvels were attributed to relics beginning in the early centuries of the Church; many of these became especially popular during the Middle Ages.

The veneration of relics was a subject of considerable disagreement between Catholics and Protestants, particularly during the Reformation and in the 17th century. While Catholics viewed relics as powerful intercessors that could bring about miracles, healings and divine intervention, most Protestants were highly critical of this practice.

For Protestants, especially those following Martin Luther or John Calvin, the veneration of relics was often seen as a form of idolatry or superstition that detracted from the worship of God. They believed that such practices were not supported by the Bible and that they had been introduced into Christianity as corruptions of original teachings. For example, in his "95 Theses," Luther directly challenged the selling of indulgences, which was closely related to the veneration of relics.

The Protestant skepticism towards relics also had political and social dimensions. The trafficking of relics had become a lucrative business, and relics were often used to attract pilgrims and their donations to specific churches or shrines. Many Protestants viewed this as a form of corruption within the Church.

The monumental architecture of the background

The foreboding, monumental architecture in a generalized classical style rises above the scene, setting the appropriate mood for the picture's somber narrative.

The composition's perspective, indicated by the orthogonals of the buildings' receding cornices, creates a deep, hollow space that evidently was meant to dramatize the saint's anguish. However, the vanishing point of the buildings does not coincide with that produced by the stone steps below. Evidently, the painter of the copy made no attempt to improve Ficherelli's less-than-firm grasp of one-point linear perspective, considered at the time a requisite for the knowledgeable history painter. In Ficherelli's original, the chiaroscuro values of the architecture seem to be treated more delicately than in the copy.

The red paint of the saint's robe

The conventionally "antique" red dress appears to have been painted with a common glaze technique using the organic ruby-red madder pigment, extracted from the madder plant. This pigment is one of the most brilliant reds available to painters. Madder has been cultivated as a dyestuff since antiquity in Central Asia and Egypt, where it was grown as early as 1500 B.C. Cloth dyed with madder root pigment was found in the tomb of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun and in the ruins of Pompeii and ancient Corinth. In the Middle Ages, Charlemagne encouraged madder cultivation. It grew well in the sandy soils of the Netherlands and became an important part of the local economy.

In order to obtain the maximum depth and vibrancy of color, painters had learned that it was important to separate the problems of rendering form from color. For example, intensely colored draperies were first modeled with relatively monochrome tones, usually using raw umber—a dull but extremely versatile natural earth pigment—for the darks and lead white for the lights. In this phase, called underpainting, the artist could focus exclusively on the distribution of light and dark. Once thoroughly dry, a somewhat syrupy mixture of naturally transparent paint mixed with drying oil was carefully glazed on top of the underpainting, giving it a full, vibrant color, especially in the lights, unattainable by direct mixture of paints. The shine-through effect is somewhat analogous to laying a sheet of colored acetate over a monochrome image. The painter of the copy seems to have used such a procedure.

Although at first glance the copy appears to be an exact replica of Ficherelli's Saint Praxedis, there are divergences in both motif and style. The copy presents a crucifix in the hands of the saint, while none is present in the original. The robust chiaroscuro scheme of the copy is more clearly stated, with lights and darks massed together in distinct areas to create a more dramatic effect of movement and light. Paint is applied more sparingly in Ficherelli's original, and both modeling and brushwork appear more nuanced.

While Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. believes that the more robust approach to painting technique can be related to some passages of Vermeer's early Christ in the House of Martha and Mary and the red blouse of the seated nymph in Diana and her Companions, conservator Jørgen Wadum sees in the work traits uncharacteristic of any known painting by Vermeer.

In the red drapery, Wadum notes curious "minute wavy strokes" of the brush of a seemingly "trembling hand" everywhere in the figure's tunic. Wadum conjectures that these very signs "reveal the artist's character," even though he admits the possibility that a conscious attempt to imitate Ficherelli's style could explain the particular stylistic trait. Wadum wrote, "As far as I can judge from photographic evidence, wavy brush-handling is not found in the Ficherelli of Ferrara on which the copy is based." He further notes that just such wavy brushwork is present in three works by Ficherelli in the National Gallery of Dublin.

The white sleeves of the saint's garments

The sleeves of the saint were painted with deft flecks of white lead, the most common white pigment in European painting. Prepared artificially since the earliest historical times and used until the nineteenth century, this warm white is semi-opaque, has outstanding brushing qualities and mixes well with every color on the artist's palette. As the name "lead white" suggests, it is a by-product of lead, and the purity of the color depends on the purity of the lead.

In the Dutch and Old German manufacturing process, known as the "stack" process, strips of lead were rolled up into spirals and placed in closed earthenware jars containing acetic acid. Subsequently, the pots were buried under tanner's bark or dung. The vinegar fumes corroded the metal and produced lead acetate, which was then converted to lead carbonate by the CO₂ and water vapor released by the rotting manure over several months. The white lead was scraped off the lead coils, washed and cleaned. White lead is extremely poisonous and must be handled with care.

In anticipation of the sale of Saint Praxedis on June 8, 2014, the painting was examined by the conservation department of the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum. Particles of lead taken from samples of white paint used in Saint Praxedis were submitted for high-precision lead isotope ratio analysis at the Free University, Amsterdam. The results established that the lead originated in northern Europe and was consistent with mid-17th-century painting in Holland. Two separate samples from the picture were then tested to confirm this result, proving that the picture was not painted in Italy as had been held by the majority of art historians. Furthermore, a lead white sample taken from Vermeer's early Diana and her Companions was tested in the same manner. According to the conservator staff, the match with the Saint Praxedis lead white was so precise as to suggest that they came from a single batch of paint used for both pictures.

However, a recent, more extensive study has demonstrated that attribution to a particular painter or workshop cannot be justified on the grounds of an identical lead white "fingerprint"' alone. This means that although the lead white in both pictures is possibly the same, it is also conceivable that other workshops used lead white from the same "batch" or produced from the same raw materials, which would also result in the same lead isotope ratio. Without a reasonable definition of the term "batch"—a batch could signify a small container kept in the artist's studio as well as multiple barrels imported to the Netherlands for a country-wide distribution— the term introduces a variable that makes the method less reliable and potentially misleading.

This recent study raises an important consideration about the limitations of relying solely on material analysis for attributing works of art to specific artists or workshops. While technical examinations can provide valuable clues about a painting's origins, they are just one piece in the complex puzzle of art historical inquiry. Provenance research, stylistic analysis and historical context also play crucial roles in making more definitive attributions. As such, the lead white "fingerprint" serves as a useful but not conclusive marker for identifying the work's creator or place of origin.

The white sleeves of the saint's garments

The sleeves of the saint were painted with deft flecks of white lead, the most common white pigment in European painting. Prepared artificially since the earliest historical times and used until the nineteenth century, this warm white is semi-opaque, has outstanding brushing qualities and mixes well with every color on the artist's palette. As the name "lead white" suggests, it is a by-product of lead, and the purity of the color depends on the purity of the lead.

In the Dutch and Old German manufacturing process, known as the "stack" process, strips of lead were rolled up into spirals and placed in closed earthenware jars containing acetic acid. Subsequently, the pots were buried under tanner's bark or dung. The vinegar fumes corroded the metal and produced lead acetate, which was then converted to lead carbonate by the CO2 and water vapor released by the rotting manure over several months. The white lead was scraped off the lead coils, washed and cleaned. White lead is extremely poisonous and must be handled with care.

In anticipation of the sale of Saint Praxedis on June 8, 2014, the painting was examined by the conservation department of the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum. Particles of lead taken from samples of white paint used in Saint Praxedis were submitted for high-precision lead isotope ratio analysis at the Free University, Amsterdam. The results established that the lead originated in northern Europe and was consistent with mid-17th-century painting in Holland. Two separate samples from the picture were then tested to confirm this result, proving that the picture was not painted in Italy as had been held by the majority of art historians. Furthermore, a lead white sample taken from Vermeer's early Diana and her Companions was tested in the same manner. According to the conservator staff, the match with the Saint Praxedis lead white was so precise as to suggest that they came from a single batch of paint used for both pictures.

However, a recent, more extensive study has demonstrated that attribution to a particular painter or workshop cannot be justified on the grounds of an identical lead white "fingerprint"' alone. This means that although the lead white in both pictures is possibly the same, it is also conceivable that other workshops used lead white from the same "batch" or produced from the same raw materials, which would also result in the same lead isotope ratio. Without a reasonable definition of the term "batch"—a batch could signify a small contained kept in the artist's studio as well as multiple barrels imported to the Netherlands for a country-wide distribution— the term introduces a variable that makes the method less reliable and potentially misleading.

This recent study raises an important consideration about the limitations of relying solely on material analysis for attributing works of art to specific artists or workshops. While technical examinations can provide valuable clues about a painting's origins, they are just one piece in the complex puzzle of art historical inquiry. Provenance research, stylistic analysis and historical context also play crucial roles in making more definitive attributions. As such, the lead white "fingerprint" serves as a useful but not conclusive marker for identifying the work's creator or place of origin.

The architectural forms: painting technique

The forms of the architectural features are painted with very thin paint, which allows the brownish underpainting to clearly be seen.

Seventeenth-century painters, especially history painters and landscape painters, employed different degrees of finish and detail to each passage of a painting according to its importance as subject matter or the distance from the spectator. In the case of the Saint Praxedis, had the background-building been painted in detail, the eye would have been attracted to the background, away from the saint.

Although the human eye cannot discern details of objects placed at a considerable distance, they generally do not seem blurry, with fuzzy edges, but simply "indistinct." This subliminal sensation can be best approximated in painting by using blurry contours and thin paint, which allows the underpainting to shine through. This technique was not generally used to the same degree by interior painters of the times; its application was more subtle. For example, the dejected gentleman in the background of Vermeer's Girl with a Glass of Wine is painted with somber, near-monochromatic tones and blurry edges, while the two foreground figures and brightly colored inner details and edges are rendered with great attention.

This was a crucial aspect of 17th-century painting techniques, underscoring the artists' understanding of human perception and the optical effects of painting. Such considerations went beyond mere aesthetic choices and revealed the intellectual depth with which artists approached their works.

The ewer

The well-known conservator Jorgen Wadum has forcefully argued against the painting's authenticity due to a number of technical issues. Here are some of his arguements.

"The way a hand applies the paint, especially when the artist is not concentrating on a specific form, results from an automatic movement of the hand and therefore reveals the individual. Of course, an artist copying another artist's painting would probably try to emulate his source's brushwork. However, the wavy brush-handling is not found in the Ficherelli original painting in Ferrara. Nevertheless, the three works by Ficherelli in the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin, The Sacrifice of Isaac (c. 1640), Lot and His Daughters, and Saint Mary Magdalen show exactly the same waviness in the brushwork as the so-called Vermeer Saint Praxedis.

"There are also other elements in this painting that cause problems in understanding its nature as a copy. When copying another artist's work one would expect the painter to work from the front toward the back, in contrast with the normal way of painting. This means that the copyist would begin by rendering the outlines of the most important Praxedis attributed to Vermeer this is not the case. The ewer in which the saint collects the blood of the beheaded man was not blocked out in the red dress before, it was painted. The red dress extends under the left quarter of the urn, indicating an initial asymmetrical object, and both handles appear to be painted over the finished red dress. Furthermore, the dark silhouette of the architecture behind the dead body was painted before the corpse. We can make this out by the fact that a dark patch of shadow is shimmering through the shoulder of the corpse. One would not expect to find these phenomena, appearing like pentimenti, in an almost literal copy. The Ficherelli painting in Ferrara does show a number of minor differences, such as the outline of the drapery on the left shoulder of the saint and the headdress against the finished sky. Reflectograms of Ficherelli's painting reveal a number of preparatory drawings, especially in the drapery, arms, and hands."

special topics

- Who was Saint Praxedis?

- Who was Felice Ficherelli?

- Why would Vermeer have copied the Saint Praxedis?

- How could the Italian painting have gotten to Delft?

- A painting with two signatures

- Where could Vermeer have seen the original Saint Praxedis by Ficherelli?

- Related artworks

EV SURVEY

Is the Saint Praxedis an authentic painting by Johannes Vermeer?

The signature

Signed and dated 1655 in the lower left, and it also carries an additional inscription in the lower right corner: "Meer N ... R ... o... o," which has been interpreted as "Meer N[aar] R[ip]o[s]o" (Vermeer after Riposo), the latter being Ficherelli's nickname.

(Click here to access a complete study of Vermeer's signatures.)

Dates

1655

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. The Public and the Private in the Age of Vermeer, London, 2000

(Click here to access a complete study of the dates of Vermeer's paintings).

Technical report

The plain-weave canvas support has a regular weft of ten threads to the centimeter. The painting has been relined.

The light brown ground consists primarily of lead white, iron oxides and calcium. A darker brown imprimatura layer exists under the sky, which is painted with natural ultramarine. The gown, lips and blood are painted with red lakes of lead white. The pigments in the yellow paint on the brim of the urn are lead white and yellow ochre. Many different textural effects have been created with the use of glazing, scumbling, impasto and dry brushstrokes.

The painting is in excellent condition, with only a few small losses along the right side and bottom.

* Johannes Vermeer (exh. cat., National Gallery of Art and Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis - Washington and The Hague, 1995, edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr.)

Provenance

- Erna and Jacob Reder, New York, 1932 [Spencer Samuels & Company, New York, 1969–1987];

- Barbara Piasecka Johnson Collection Foundation; 1987

Exhibitions

- New York 1969

Florentine Art from American Collection

Metropolitan Museum of Art

44–45, no. 39 and ill. 22. - New York 1984

Inaugural Exhibition

Spencer A. Samuels Gallery

no. 14 - Warsaw 1990

Opus Sacrum. Catalogue of the Exhibition from the collection of Barbara Piasecka Johnson

Royal Castle

11, 272–277, no. 48 and ill. - Cracow 1991

Jan Vermeer van Delft (1632–1675). Saint Praxedis: An Exhibition of a Painting from the Collection of Barbara Piasecka Johnson. International Cultural Center

Warsaw Royal Castle

8–28, and several ills. - Washington D.C November 12, 1995–February 11, 1996

Johannes Vermeer

National Gallery of Art

86–89, no.1 and ill. - The Hague March 1–June 2, 1996

Johannes Vermeer

Mauritshuis

86–89, no.1 and ill. - Monaco 1998

Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675: Sainte Praxède/Saint Praxedis)

Musée de la Chapelle de la Visitation - Osaka April 4–July 2, 2000

The Public and the Private in the Age of Vermeer

Osaka Municipal Museum of Art

174–177, no. 31 and ill. - Rome September 27, 2012–January 20, 2013

Vermeer: Il secolo d'oro dell'arte olandese

Scuderie del Quirinale

200, no. 45a and ill. - Tokyo March 17, 2015

Saint Praxedis

National Museum of Western Art - Amsterdam February 10– June 4, 2023

VERMEER

Rijksmuseum

no. 2 and ill.

(Click here to access a complete, sortable list of the exhibitions of Vermeer's paintings).

Who was Saint Praxedis?

According to legend, Saint Praxedis was a 2nd-century daughter of a disciple of St. Paul living in Rome and sister of Saint Pudentiana. When Emperor Marcus Antoninus was hunting down Christians, Saint Praxedis sought them out to relieve them with money, care and comfort. Some she hid in her house, others she encouraged to keep firm in the faith. She likewise cared for the severed bodies of those martyred for their faith.

Saint Praxedis was at first venerated as a martyr in connection with the Ecclesia Pudentiana, but afterward, a separate church was built in her honor, on the alleged site of her house. When it was rebuilt by Pope Saint Paschal I (the present Santa Prassede), her relics were taken there.

By the late 16th century, she was especially revered by the Jesuits, an order that lived next door to Vermeer's mother-in-law, Maria Thins, who lived along the Oude Langendijk in Delft. Although baptized in the Reformed Church, Vermeer converted to Catholicism around the time of his marriage in 1653 and maintained Jesuit connections throughout his life. He even named his youngest son Ignatius, likely after the founder of the Jesuit Order. The subject of St. Praxedis aligns with Vermeer's broader thematic focus on the dignity of service, as seen in other early works like "Christ in the House of Martha and Mary."

In the two paintings by Vermeer and Ficherelli, Saint Praxedis is shown kneeling in front of an ornate twin-handled jug into which she is squeezing a sponge soaked with the blood of a decapitated martyr.

Her effigy appears on a mosaic of the Catholic Church of Saint Praxedis in Rome.

Who was Felice Ficherelli?

The Death of Cleopatra

Felice Ficherelli

1650s

Oil on canvas, 71 x 78 cm.

National Gallery of Slovenia, Ljubljana

The Saint Praxedis is indisputably a copy of a painting by Felice Ficherelli. The original composition was first described by Filippo Baldinucci (1625–1697), an Italian art historian and biographer, renowned for his extensive writings on artists from the Italian Renaissance and Baroque period, in 1681. There are two variants of Ficherelli's work, one presumably by Vermeer, and another in the possession of the Dorotheum auction house. A preparatory drawing by Ficherelli also exists. The copy in question was initially part of the Collection Carlo del Bravo in Florence. It later entered a private collection in Ferrara and was attributed to Vermeer. Subsequently, it was sold at Christie's in London for 7.9 million euros. The buyer was an unidentified Asian collector. The painting is now the property of the Kufu Company Inc. and is on long-term loan to the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo.

Felice Ficherelli (1605–1660) was an Italian Baroque painter primarily active in Tuscany. He earned the nickname "il Riposo" (the restful) which seems to contrast sharply with the thematic content of his works. Ficherelli had a penchant for painting rather intense and, at times, violent subjects. These were often depictions of martyrdoms or historical murders. His treatment of such themes was notably marked by a sort of morbid sensuality and an ambiguous tenderness, making his approach unique in the scope of Baroque painting.

Ficherelli had the opportunity for formal artistic training thanks to Conte Alberto Bardi, an influential collector who took the young artist to Florence. There, Ficherelli studied under Jacopo da Empoli and had the chance to copy works by Andrea del Sarto. His compositions often displayed a clarity and luminous quality in the drapery of the figures, traits that remained consistent throughout his career.

How Vermeer might have come across the Saint Praxedis, which has never left Italy and is now in a private collection in Ferrara, remains unsolved.

The Rape of Lucretia

Felice Ficherelli

Late 1630s

Oil on tinned copper, 24.5 x 29.9 cm.

Wallace Collection, London

Why would Vermeer have copied Ficherelli's Saint Praxedis?

A Young Boy Copying a Painting

After Wallerant Vaillant

1660

oil on canvas, 127 x 99.5 cm.

National Gallery, London

A painting with two signatures

This painting, a close copy of a painting by the Florentine master Felice Ficherelli curiously, displays two signatures. The first to be noticed was "Meer 1655" in the lower left. It also carries an additional inscription which had escaped the experts' eyes for some time in the lower right corner: Meer N ... R ... o... o, which has been interpreted as Meer N[aar] R[ip]o[s]o (Vermeer after Riposo), the latter being Ficherelli's nickname.

After consulting the results of laboratory examination, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. claimed that both "signatures and the date are integral to the paint surface" but is at a loss as to why the work bears two signatures.

Conservator Jørgen Wadum, on the other hand, states that the signature to the lower left is clearly not part of the original paint layer. He argues that the paint layer directly beneath it is visibly abraded (which means it has undergone some wear and tear) while the signature above seems relatively fresh and clear. Wadum remarks that the second signature to the lower right "is so rudimentary that any interpretation would be factitous." Furthermore, two signatures on the same painting would be a rarity for a 17th-century copy.

Conversely, Gregor Weber has argued there is no reason to discount the authenticity of the signatures. He believes substantial evidence seems to be provided by the analysis of the signature, which is on the original layer of paint and was therefore not a later addition. Thus, it is also very unlikely that the signature was added with the intention of forgery, since Vermeer's commercially exploitable fame did not take off until the latter half of the nineteenth century. The question remains, however, whether Ficherelli's original was anywhere near where Vermeer was working around 1655 and who might have had an interest in a picture of this Catholic saint.

Moreover, a second—today scarcely legible—notation on the painting was once deciphered as "Meer N R[..]o[.]o," which, according to Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann, could be read as "naar Riposo" (after Riposo), Ficherelli's nickname. However, a place name with the Latin form of "Rhoon," or "Rooden," is just as plausible and, in signatures, even more common than the name of the painter of the original. Such a reading was also put forward by Hans Slager, who only recently noticed a surprising connection of Vermeer to Rhoon Castle from a completely different angle, a similarity of leaded windows in Vermeer's painted interiors to those in Rhoon.

Where could Vermeer have seen the original Saint Praxedis by Ficherelli?

The copy of Ficherelli's Saint Praxedis is, perhaps the most debated candidates in regard to its authenticity. Since it is a very faithful copy of an extant painting, which almost certainly never left the country, various scholars believe this fact alone is sufficient to disqualify it from Vermeer's oeuvre.

However, various hypotheses exist that, while not proving Vermeer made the copy himself, show that it is not out of the question. First of all, Vermeer could have made his copy from another copy that had somehow reached the Netherlands. Copies of Italian paintings were highly regarded in the Netherlands and were part of an active market. In Delft, various paintings by Italian masters were known to have been part of private collections. When John Michael Montias, Vermeer's biographer, made a scrupulous examination of Delft's archival records, only five turned up, of which only three were probably copies. It is far likelier that originals and copies by Italian masters could be found in Amsterdam. One Amsterdam art dealer, Johannes de Renialme, owned ten. Curiously, de Renialme also had in his collection a now-lost Grave Visitation by Vermeer, presumably an early work. De Renialme was also in contact with Vermeer through his family's notary, Willem de Langue. The fact that Vermeer was summoned to The Hague to judge the authenticity of a group of disputed "Italian masterpieces" suggests that his knowledge of Italian painting must have circulated among artists and art lovers.

Gregor Weber, a leading Vermeer expert who has written extensively about Vermeer's connections with the Jesuit order, believes that the painting and its theological context fit well with the Jesuit priests' interests. This is given their excellent connections to Italy and frequent travel between Rome, Flanders and mission territories like Holland. The dating of the painting to 1655 aligns with the refurbishment of the Jesuit church after a gunpowder explosion in 1654. While speculative, it's conceivable that a copy of St Praxedis could have been commissioned from the young Vermeer due to the Delft Jesuits' travels to Rhoon. Additionally, a barely legible notation on the painting could be interpreted in various ways, including as a reference to Ficherelli's nickname or the location of Rhoon (a second, today scarcely legible, notation on the painting was once deciphered as "Meer N R[..]o[.]o,", which, according to Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann, could be read as "naar Riposo" (after Riposo), Ficherelli's nickname. However, a place name with the Latin form of "Rhoon,", or "Rooden" is just as plausible and in signatures even more common than the name of the painter of the original). This is further supported by a recent observation of similar leaded windows in Vermeer's painted interiors and those in Rhoon Castle.

A second, but less convincing, explanation concerns Vermeer's presumed visit to Italy. Another Dutch painter named Johannes Vermeer is documented to have been in Italy in the 1650s, but scholars firmly believe that it was Johannes Vermeer of Utrecht, who, coincidentally, worked in the Italian manner.

How could the St. Praxedis gotten to Delft&

Critics have long questioned how an Italian painting like St. Praxedis could have found its way to Delft and why Vermeer would have painted it. Gregor Weber suggests that interest in Ficherelli’s painting, and a copy based on it, would align theologically with Jesuit circles, who were active in Delft and had strong connections to Italy. Since Jesuits reported directly to the pope, they frequently traveled between Rome, Flanders, and mission territories like Holland. Given this extensive network, Weber believes it is plausible that someone brought or delivered Ficherelli's composition to the north. The painting's date, 1655, coincides with the refurbishment of the Jesuit church after the gunpowder explosion in October 1654. With the donations received, objects could have been ordered or purchased.

However, the exact circumstances of how a copy of St. Praxedis came to be in Delft remain speculative. An Italian painting like Ficherelli’s would not have been out of place in Rhoon Castle, situated just south of Rotterdam, along the Oude Maas River. The castle has historical significance, dating back to the 13th century, and has been associated with various noble families over the centuries. During the 17th century, when Vermeer was active, the castle was a Catholic stronghold, which made it an important site for religious and cultural exchanges. and it is conceivable that Vermeer was commissioned to make a copy as a result of the Delft Jesuits' travels to Rhoon. Archivist Hans Slager was the first to connected Vermeer to Rhoon Castle through the Jesuit network, particularly through Jesuit priest Isaac van der Mye. Van der Mye, a former chaplain at Rhoon Castle (1645–1650), played a significant role in the religious and cultural exchanges between the Catholic stronghold of Rhoon and Delft. After being assigned to the Jesuit station in Delft, Van der Mye’s involvement in expanding the local house church suggests possible artistic or devotional collaborations that could have influenced Vermeer. The chapel at Rhoon, richly furnished with religious art, and Van der Mye’s connections to both locations, provided a channel for art and religious materials to move between Rhoon and Delft, possibly including commissions like St. Praxedis.

Moreover, a second, now mostly illegible, signature on the painting was once deciphered as "Meer N R[..]o[.]o". Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann interpreted this as "naar Riposo" (after Riposo, Ficherelli’s nickname). However, it is also plausible that the inscription refers to a place name like "Rhoon" or "Rooden," which was common in signatures. Hans Slager supported this interpretation and recently noted a surprising connection between Vermeer and Rhoon Castle from another angle—a similarity between the leaded windows in Vermeer’s painted interiors and those found in Rhoon Castle.