Study of a Young Woman

(Meisjeskopje)c. 1665–1674

Oil on canvas, 44.5 x 40 cm. (17 1/2 x 15 3/4 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

acc. no. 1979.396.1

The textual material contained in the Essential Vermeer Interactive Catalogue would fill a hefty-sized book, and is enhanced by more than 1,000 corollary images. In order to use the catalogue most advantageously:

1. Scroll your mouse over the painting to a point of particular interest. Relative information and images will slide into the box located to the right of the painting. To fix and scroll the slide-in information, single click on area of interest. To release the slide-in information, single-click the "dismiss" buttton and continue exploring.

2. To access Special Topics and Fact Sheet information and accessory images, single-click any list item. To release slide-in information, click on any list item and continue exploring.

The young girl

Girl with a Pearl Earring (detail)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1665–1667

Oil on canvas, 46.5 x 40 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

Although this young girl is not as immediately appealing as the adolescent who posed for Girl with a Pearl Earring, she emanates a moon-like beauty that becomes most readily appreciable only when observing the actual painting.

The remarkably soft lighting and subtle handling of chiaroscuro effects differ substantially from the technique Vermeer employed in Girl with a Pearl Earring. Notable in this painting is the lack of linear definition of the facial features, as well as the blurry contour of her face, which contrasts with the crisp definition of the blue satin wrap.

According to John Michael Montias, "the girl's widely spaced eyes bear a sufficient resemblance to those of the young man with the beret in The Procuress to suggest she may have been the artist's daughter. Vermeer was married in April 1653. His oldest daughter, Maria, could not have been much older than thirteen in 1666–1667 or twenty in 1672–1674, the two widely separated dates that Wheelock and Blankert respectively assign to the Wrightsman head. If the head does represent Maria, the later date must be closer to the truth. It is hardly conceivable that Maria or her younger sister Elisabeth could have been portrayed in Girl with a Pearl Earring, which is generally dated about 1665 when the older of the two sisters was less than twelve years old."

The young girl's wrap

There are few examples in Vermeer's art where the shimmer of satin is so successfully captured. The material's crackling texture and razor-sharp, haphazard folds, "carelessly" draped over the girl's shoulder, provide a perfect foil for the ethereal softness of her skin and the symmetry of her features. Her disarming adolescence leaves almost any reasonably sensitive viewer with an impression of a human encounter that is unforgettable.

The silver-blue fabric appears to be some kind of heavy satin or silk. Small dots of light-toned paint are speckled here and there. It is difficult to determine whether they were meant to imitate the — produced by camera obscura vision or the fabric's coarse weave.

Many art historians believe that this picture might have been one of the three tronies "in antique dress" described as "uncommonly artful" and sold in the 1696 posthumous Amsterdam auction of 21 paintings by Vermeer. In Vermeer's possessions at the time of his death were listed another "two tronien in Turkish fashion," which, although not mentioned as being done by Vermeer, have nonetheless been tentatively proposed as Girl with a Pearl Earring and the present work. A bolt of particularly flashy cloth artistically draped over the shoulder of any light-skinned Dutch girl was sufficient to qualify the resulting image as "antique." However, the oversized drop pearl earring was clearly a contemporary costume accessory, not a genuine pearl, but a contemporary imitation or artistic invention.

Some writers believe to have caught the artist off guard regarding the hand to the lower left. Instead, this discreet, yet essential passage connects the face of the girl to the unseen anatomy beneath the silken material. And it informs the viewer that her forearm is leaning on something, perhaps the bottom of the picture frame. It is Vermeer's fascination with what he sees rather than what he knows, as the Vermeer writer Lawrence Gowing first pointed out, that lends her wrist, and not her hand, the peculiar but fascinating form that it assumes on the picture plane.

The scarf hanging from the girl's head

Boy in a Turban Holding a Nosegay

Michiel Sweerts

1656–1658

Oil on canvas, 76.4 x 61.8 cm.

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Like every other element in this canvas, the slender scarf attached to the young woman's hairdo is painted with greater delicacy than that of the Girl with a Pearl Earring, very likely its pendant. The fact that it drapes much lower, completely out of the picture, gives the work a somewhat antique air, different from the more contemporary appearance of its counterpart. Perhaps Vermeer drew inspiration for the color scheme from an extraordinary bust by Michael Sweerts, often linked to Vermeer in recent scholarship. Like Vermeer, Sweerts never bows to convention, even when he works within apparently well-trodden genres and styles. The works of both painters are imbued with a nagging, uncommon ambiguity that is as disconcerting as it is fascinating.

However, whether or not Vermeer ever had any real contact with Sweerts or had ever seen Boy in a Turban Holding a Nosegay is a matter of speculation. It is possible that Vermeer arrived at this particular pictorial solution independently. Busts of exotic female figures set against dark backgrounds were far from rare in the Netherlands.

The pearl earring

The drop pearl earring, although probably a product of the artist's imagination, is similar to that worn by the Girl with a Pearl Earring. Undisturbed by direct light, it nestles softly in the tender penumbra cast by the girl's oval face. On close inspection, it has been modeled with astounding economy: no trace of line defines its contour, but rather a few faint smudges of gray, slightly lighter than the underlying brownish tone of the neck.

In the 17th century, pearls were an important status symbol. In 1660, Samuel Pepys, an English diarist, paid 4 1/2 pounds for a pearl necklace, and in 1666 he paid 80 pounds for another, which at the time amounted to about 45 and 800 guilders, respectively (Pepys' wife feared he might not be able to distinguish real from fake pearls). At about the same time, the traveling French art connoisseur Balthasar de Monconys had been shown a single-figure painting by Vermeer for which 600 guilders had been paid. The Frenchman considered the price outrageous.

Like all rare and expensive natural products, a convincing alternative to the costly pearl was sought. In Ancient Rome, glass beads were coated with silver and then coated again with glass in an attempt to replicate the luster of pearls. Fake pearls were produced in Italy. In France, before the 15th century, hollow glass beads were dipped into acid to produce an iridescent surface. In the 17th century, an improved version was produced in France by a rosary maker in Paris named M. Jacquin. First, the interior of the beads was coated with a substance called essence d'orient, which was nothing but ground fish scales, to provide a nacreous appearance (it is said that Jacquin noticed that water containing scales from the ablette, or bleak, produced reflections that resembled those produced by the nacre on a natural pearl). This mixture was then poured into the beads and agitated so that their insides might be completely coated. These beads were filled with wax to provide solidity and weight. Before Jacquin's invention of essence d'orient, mercury was used to give clear-glass beads the luster of pearls.

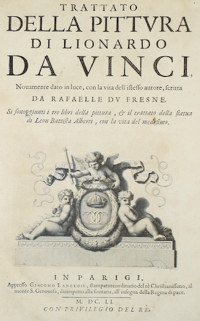

The dark background

Dark backgrounds were widely used in portraiture to isolate the figure from distracting elements and enhance its three-dimensional effect. In fragment 232 of his Trattato (Treatise on Painting), Leonardo da Vinci noted that a dark background makes an object appear lighter, and vice versa.

It was long believed that Vermeer exploited the same effect in the celebrated Girl with a Pearl Earring, perhaps a pendant to the present painting. However, it has recently been discovered that the background of the Girl with a Pearl Earring once featured a deep green, drawn-back curtain, which makes the likelihood of the two works being pendants less probable.

The young girl's "strange" hand

The Art of Painting (detail)

c. 1662–1668

Oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

In the later years of his career, Vermeer seems to have more than occasionally disregarded anatomical correctness altogether. Robert Hale, the American painter and author of the first monograph dedicated to Vermeer in the United States, believes he was simply unable to achieve it. The bulbous hand of the seated artist in The Art of Painting is one of the most noted anatomical distortions in the artist's oeuvre. Lawrence Gowing, like Hale himself a painter, excused the artist for this and claimed that such distortions were deliberate.

In an oft-quoted passage of his influential interpretation of Vermeer's painting, Gowing wrote: "In Vermeer we have to deal with something quite outside the painterly fullness of tone which was so often the burden of pictorial evolution between Masaccio and Rembrandt. His is an almost solitary indifference to the whole linear convention and its historic function of describing, enclosing, embracing the form it limits, a seemingly involuntary rejection of how the intelligence of painters has operated from the earliest times to our own day. Even now, when the photographer has taught us to recognize visual as against imagined continuity, and in doing so no doubt blunted our appreciation of Vermeer's strangeness, the feat remains as exceptional as it is apparently perverse, and to a degree which may not be easy for those unconcerned with the technical side of a painter's business to measure. However firm the contour in these pictures, line as a vessel of understanding has been abandoned and with it the traditional apparatus of draftsmanship. In its place, apparently effortlessly, automatically, tone bears the whole weight of formal explanation."

But in other paintings, it is more difficult to accept Gowing's point of view. For example, the fingers and wrists of the figure in Allegory of Faith are so poorly defined that they look more like rubber gloves filled with water than real hands. The extended arm and claw-like hand of the seated figure in Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid can be pardoned only because it was painted by Vermeer, and the arms and fingers of A Lady Seated at a Virginal are so unusually rendered that one prominent Dutch art historian labeled them "pig trotters." And concerning the present painting, we know the patch of flat flesh tone represents the figure's wrist only because we are so familiar with human anatomy.

special topics

What were 17th-century Dutch women like?

The Wrightsman (Study of a Young Woman) and the Mauritshuis (Girl with a Pearl Earring) paintings are almost identical in size and are close in composition: the figures are similarly posed against dark backgrounds, and each wears a pearl earring and an elegant scarf that falls behind her head. The models may or may have not been Vermeer's daughters, but neither picture was painted as a portrait. The paintings are studies of expression, physical types, and visual qualities such as the behavior of light. Whether the two canvases were conceived as pendants, which would have been exceptional for tronien, is quite uncertain but cannot be dismissed out of hand.

Walter Liedtke, Vermeer and the School of Delft, 2001

The signature

Signed upper left: IVMeer [IVM in monogram]

(Click here to access a complete study of Vermeer's signatures.)

Dates

1672–1674

Albert Blankert, Vermeer: 1632–1675, 1975

c. 1667–1668

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., The Public and the Private in the Age of Vermeer, London, 2000

c. 1665–1667

Walter Liedtke, Vermeer: The Complete Paintings, New York, 2008

c. 1665–1667

Wayne Franits, Vermeer, 2015

(Click here to access a complete study of the dates of Vermeer's paintings).

Provenance

- (?) Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven, Delft (d. 1674);

- (?) his widow, Maria de Knuijt, Delft (d. 1681);

- (?) their daughter, Magdalena van Ruijven, Delft (d. 1682);

- (?) her widower, Jacob Abrahamsz Dissius (d. 1695);

- Dissius sale, Amsterdam, 16 May, 1696, no. 38, 39 or 40 [tronien];

- Jan Luchtmans, Rotterdam (in 1816);

- Luchtmans sale, Rotterdam, 20 April, 1816, no. 92;

- Auguste Marie Raymond, prince d'Arenberg, Brussels (by 1829-d.1833);

- Arenberg family, Brussels and Schloss Meppen, Germany (1833–1945);

- Engelbert-Marie, 9th duc d'Arenberg, Brussels, Schloss Meppen and Schloss Nordkirchen, Germany (1945-d.1949);

- his son, Engelbert-Charles, 10th duc d'Arenberg (1949–1955);

- sold through Germain Seligman to Wrightsman);

- Mr and Mrs Charles Wrightsman, New York (1955–1979);

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr and Mrs Charles Wrightsman, in memory of Theodore Rousseau Jr., 1979 (acc. no. 1979.396.1).

Exhibitions

- Düsseldorf August 1904

Kunsthistorische Ausstellung

Location unknown

no. 398, lent by Herzog von Arenberg, Brussels - The Hague June 25–September 5, 1966

In het licht van Vermeer

Mauritshuis

no. VI, lent by Mr. and Mrs. Charles B. Wrightsman, New York and Palm Beach - Paris September 24–November 28, 1966

Dans la lumière de Vermeer.

Musée de l'Orangerie

no. VII, lent by Mr. and Mrs. Charles B. Wrightsman, New York and Palm Beach - New York March 8–May 27, 2001

Vermeer and the Delft School

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

no. 75 - New York September 18, 2007–January 6, 2008

The Age of Rembrandt: Dutch Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Metropolitan Museum of Art

no catalogue - New York October 24, 2008–February 1, 2009

The Philippe de Montebello Years: Curators Celebrate Three Decades of Acquisitions

Metropolitan Museum of Art

online catalogue - New York September 9–November 29, 2009

Vermeer's Masterpiece "The Milkmaid"

Metropolitan Museum of Art

no. 9 and ill.

(Click here to access a complete, sortable list of the exhibitions of Vermeer's paintings).

| Vermeer's life | Pieter van Ruijven and his wife Maria Knuijt leave 500 guilders to Vermeer in their last will and testament. This kind of a bequest is very unusual and testifies a close relationship between Vermeer and Van Ruijven that went beyond the usual patron/painter one. It would seem that in his life-time the rich Delft burger had bought a sizable share of Vermeer's artistic output. |

| Dutch painting |

Rembrandt paints The Jewish Bride. Adriaen van Ostade paints The Physician in His Study. c. 1665 Gerrit Dou painted Woman at the Clavichord and a Self-Portrait in which he resembled Rembrandt. |

| European painting & architecture |

Bernini finishes high altar, Saint Peter's, Rome (begun 1656). Murillo: Rest on the Flight into Egypt. Nicolas Poussin, French painter, dies. Known as the founder of French Classicism, he spent most of his career in Rome which he reached at age 30 in 1624. His Greco-Romanism work includes The Death of Chione and The Abduction of the Sabine Women. Compagnie Saint-Gobain is founded by royal decree to make mirrors for France's Louis XIV. It will become Europe's largest glass-maker. Francesco Borromini completes Rome's Church of San Andrea delle Fratte. |

| Music |

Molière: Don Giovanni. Sep 22, Moliere's L'amour Medecin, premiered in Paris. |

| Literature |

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society begins publication. |

| Science & philosophy |

Giovanni Cassini determines rotations of Jupiter, Mars, and Venus. Peter Chamberlen, court physician to Charles 11, invents midwifery forceps Pierre de Fermat, French mathematician, dies. His equation xn + yn = zn is called Fermat's Last Theorem and remained unproven for many years. The history of its resolution and final proof by Andrew Wiles is told by Amir D. Aczel in his 1996 book Fermat's Last Theorem. Fermat's Enigma: The Epic Quest to Solve the World's Greatest Mathematical Problem by Simon Singh was published in 1997. In 1905 Paul Wolfskehl, a German mathematician, bequeathed a reward of 100,000 marks to whoever could find a proof to Fermat's "last theorem." It stumped mathematicians until 1993, when Andrew John Wiles made a breakthrough. Francis Grimaldi: Physicomathesis de lumine (posth.) explains diffraction of light. Isaac Newton experiments on gravitation; invents differential calculus. Robert Hooke's Micrographia, with illustrations of objects viewed through a microscope, is published. The book greatly influences both scientists and educated laypeople. In it, Hooke describes cells (viewed in sections of cork) for the first time. Fundamentally, it is the first book dealing with observations through a microscope, comparing light to waves in water. Mathematician Pierre de Fermat dies at Castres January 12 at age 63, having (with the late Blaise Pascal) founded the probability theory. His remains will be reburied in the family vault at Toulouse. |

| History |

English naval forces defeat a Dutch fleet off Lowestoft June 3 as a Second Anglo-Dutch war begins, 11 years after the end of the first such war. General George Monck, 1st duke of Albemarle, commands the English fleet, Charles II bestows a knighthood on Irish-born pirate Robert Holmes, 42, and promotes him to acting rear admiral, giving him command of the new third-rate battleship Defiance, but the Dutch block the entrance to the Thames in October. Feb 6, Anne Stuart, queen of England (1702–1714), is born. At least 68,000 Londoners died of the plague in this year.

The second war between England and the United Provinces breaks out. It will last until 1667 and devastate the art market. Mar 11, A new legal code was approved for the Dutch and English towns, guaranteeing religious observances unhindered. Nov 7, The London Gazette, the oldest surviving journal, is first published. Ceylon becomes important trade centre for the VOC. |

| Vermeer's life |

The Concert presents a very similar deep spatial recession similar to the earlier Music Lesson. Vermeer's interest in the accurate portrayal of three dimensional perspective to create such an effect was shared by other interior genre painters of the time, however, only Vermeer seems to have fully and consciously understood the expressive function of perspective. The two paintings' underlying theme of music between male and female company is also analogous although few critics believe they were conceived as a pendant. In the paintings of the 1660s the painted surfaces are smoother and less tactile, the lighting schemes tend to be less bold. These pictures convey and impalpable air of reticence and introspection, unique among genre painters with the possible exception of Gerrit ter Borch. |

| Dutch painting | Frans Hals, eminent Dutch portrait painter, dies. It was formerly believed that he died in the Oudemannenhuis almshouse in Haarlem which was later became the Frans Halsmuseum. |

| European painting & architecture |

François Mansart, French architect, dies. Apr 9, 1st public art exhibition (Palais Royale, Paris). |

| Music | Dec 5, Francesco Antonio Nicola Scarlatti, composer, is born. |

| Literature | Le Misanthrope by Molière is palyed at the Palais-Royal, Paris. |

| Science & philosophy |

Laws of gravity established by Cambridge University mathematics professor Isaac Newton, 23, state that the attraction exerted by gravity between any two bodies is directly proportional to their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. Newton has returned to his native Woolsthorpe because the plague at Cambridge has closed Trinity College, where he is a fellow; he has observed the fall of an apple in an orchard at Woolsthorpe and calculates that at a distance of one foot the attraction between two objects is 100 times stronger than at 10 feet. Although he does not fully comprehend the nature of gravity, he concludes that the force exerted on the apple is the same as that exerted on Earth by the moon. Calculusis invented by Isaac Newton will prove to be one of the most effective tool for scientific investigation ever produced by mathematics. Nov 14, Samuel Pepys reported the on first blood transfusion, which was between dogs. The plague decimates London and Isaac Newton moved to the country. He had already discovered the binomial theorem at Cambridge and was offered the post of professor of mathematics. Newton formulates his law of universal gravitation. A French Academy of Sciences (Académie Royale des Sciences) founded by Louis XIV at Paris seeks to rival London's 4-year-old Royal Society. Jean Baptiste Colbert has persuaded the king to begin subsidizing scientists. Christiaan Huygens, along with 19 other scientists, is elected as a founding member. After the French Revolution, the Royale is dropped and the character of the academy changes. It later becomes the Institut de France. |

| History |

Sep 2, The Great Fire of London, started at Pudding Lane, began to demolish about four-fifths of London when in the house of King Charles II's baker, Thomas Farrinor, forgets to extinguish his oven. The flames raged uncontrollably for the next few days, helped along by the wind, as well as by warehouses full of oil and other flammable substances. Approximately 13,200 houses, 90 churches and 50 livery company halls burn down or explode. But the fire claimed only 16 lives, and it actually helped impede the spread of the deadly Black Plague, as most of the disease-carrying rats were killed in the fire. Because almost all European paper is made from recycled cloth rags, which are becoming increasingly scarce as more and more books and other materials are printed, the English Parliament bans burial in cotton or linen cloth so as to preserve the cloth for paper manufacture. |

| Vermeer's life |

Vermeer's name is mentioned in a poem by Arnold Bon in Dirck van Bleyswijck's Beschryvinge der Stadt Delft (Description of the City of Delft) published in 1667. It is the most significant and direct reference to Vermeer's art to be found. The poem written by Arnold Bon, Bleyswyck's publisher, was composed in the honor of Carel Fabritius who had died in the famous ammunitions explosion. Vermeer's name is lauded in the poem's last stanza.

Maria Thins empowers Vermeer to collect various debts owed to her and to reinvest the money according to his will and discretion. Vermeer's mother-on-law evidently maintained her moral and financial support of Vermeer and his family. Another of Vermeer's children is buried in the New Church in Delft. |

| Dutch painting | Gabriel Metsu, ecclectic Dutch painter, dies. |

| European painting & architecture |

Francesco Borromini, Italian sculptor and architect, dies. Borromini designed the San Ivo della Sapienza church in Rome. Alonso Cano, Spanish painter and architect, dies. |

| Music | German composer-organist-harpsichordist Johann Jakob Froberger dies at Héricourt, France. His keyboard suites will be published in 1693, arranged in the order that will become standard: allemande, courante, sarabande, and gigue. |

| Literature |

Paradise Lost is written by John Milton, who has been blind since 1652 but has dictated to his daughters the 10-volume work on the fall of man, Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven. Milton's Adam questions the angel Raphael about celestial mechanics, Raphael replies with some vague hints and then says that "the rest from Man or Angel the great Architect did wisely conceal and not divulge His secrets to be scann'd by them who ought rather admire." The work enjoys sales of 1,300 copies in 18 months and will be enlarged to 12 volumes in 1684, the year of Milton's death; Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden is about the Dutch War and last year's Great Fire. Nov 7, Jean Racine's Andromaque, premiered in Paris. |

| Science & philosophy | National Observatory, Paris, founded |

| History | Pope Alexander VII dies. Giulio Rospigliosi becomes Pope Clement IX.

c. 1667 In France, during the reign of King Louis XIV, the fork begins to achieve popularity as an eating implement. Formerly, only knives and spoons had been used. Jun 18, The Dutch fleet sailed up the Thames and threatened London. They burned 3 ships and capture the English flagship. Jun 21, The Peace of Breda endsthe Second Anglo-Dutch War (1664–1667) and sees the Dutch cede New Amsterdam (on Manhattan Island) to the English in exchange for the island of Surinam. De Verstandige Kok (The Sensible Cook) is published for the first time. Geared towards middle- and upper middle-class families, the book advises a regular and balanced diet, including fresh meat at least once a week, frequent servings of bread and cheese, stew, fresh vegetables and salads. While simple dishes, such as porridge, pancakes and soup with bread are eaten by all classes, studies reveal that only the affluent have regular access to fresh vegetables during the period; the less wealthy depend on dried peas and beans. |

What were 17th-century Dutch women like?

Double Portrait of Isaac Massa and

Beatrix van der Laen (detail)

Frans Hals

c. 1622

Oil on canvas, 140 x 166.5 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Even though the United Provinces had the most vigorous and well-distributed wealth in Europe, the differences between social classes were nonetheless stark. At the bottom of the social ladder, women lived in a perpetual state of undernourishment. Life was a daily struggle with disease, tragic living and working conditions, as well as the dangers of constant childbirth. Living conditions were so strenuous that few were overweight, and the average height was about 1.54 meters.

Wealthy women were much better off and hardly moderate in their consumption. Women rarely worked enough to offset their daily intake of calories. They avoided strenuous activities and seldom carried out heavy domestic chores, which were delegated to their servants, even though they habitually accompanied their servants to the markets. Their diet included large amounts of meat, fish, fruit, sweets and abundant imported wines and gastronomic delicacies. They had more money and time to care for their appearances, although a considerable number of formal portraits clearly show that women of the upper classes were generally corpulent. However, at least in the second half of the 17th century, they were exquisitely dressed. Affluent women had an average height of about 1.59 meters.

An unequivocal point to be made is that Dutch women were notably better off than women in the rest of Europe. This is upheld by eyewitness reports, including those from numerous foreign observers who were both delighted and appalled by what they had experienced.

From a legal standpoint, Dutch women enjoyed significant advantages over their European counterparts. Dutch women could inherit and bequeath property in their own right. If they were wronged during their marriage, they had legal recourse. Vermeer's mother-in-law was able to obtain a significant portion of her husband's money after years of physical and moral mistreatment. Adultery, unusual abuse, or willful desertion could bring about a "separation of table and bed," effectively annulling the union.

Truth or cosmetics?

Young Girl with a Guitar (detail)

Gerrit van Honthorst

Oil on canvas, 82 x 58 cm.

Musée du Louvre, Paris

While it is true that none of the women who posed for Vermeer are conventional beauties, they are not without their own unique charm. But how much effort did Vermeer and other artists expend to improve the appearance of their models?

As Eddy de Jongh pointed out, "Just how drastically cosmetic interventions were applied is hard to say, but it is a fair assumption that not every painted face with regular features, and not every painted peach skin was an accurate depiction of the original. The mere fact that the vast majority of faces in 17th-century paintings are smooth and unblemished is enough to make us suspicious, given the prevalence of smallpox epidemics at the time. Smallpox was a dreaded disease against which all remedies were helpless, and those who survived it were generally left disfigured by pockmarks. Among women of the higher classes, in particular, pockmarks are known to have aroused feelings of shame."

In any case, the use of cosmetics in the 17th century by wealthy middle and upper-class women and men both for nurturing and decorative effects, is undeniable. Their popularity is evident in numerous surviving recipes by apothecaries and quacks, as well as in the frequent depiction of powder brushes, small bottles or boxes for oils, creams or perfumes in the popular "Lady at her toilet" scenes. Although the Dutch drew heavily from the fashionable French court of Louis XIV to enhance their lifestyle, Dutch women were, and still are, famous for their clear, soft complexions, which some attribute to the moist air of the Netherlands.

A pale complexion was universally desired, as it indicated wealth. Besides avoiding sunburns and daily washings with warm water and soap mixed with herbs and spices, makeup was used to make the skin appear as fair as possible. Among the recipes to lighten the color of the skin, ladies would apply a mixture of powdered white chalk or white lead with egg whites and vinegar. While the use of chalk is harmless, ceruse, which was also used, is very harmful because it is made of poisonous lead. A woman could also wash herself with her own urine or with a decoction of lemon rinds. A late 17th-century recommendation was to rub the face with poppy seed oil and then use a white powder made of calcinated bone.

It is impossible to know whether the bright red lips seen in many portraits were natural, artificially enhanced with makeup, or the fruit of the client's imagination and the artist's skill. A variety of rouge pigments were available. Tinctures made of boiled crabs, sandalwood, brazilwood, carnation, cloves or cardamoms would provide a safe rouge. On the other hand, vermilion, a very poisonous red pigment derived from mercury and a standard pigment on the palette of every painter, was used. Cochineal, which was also used by painters, could be found in both warm and cold red tones.

Shaved forehead?

In keeping with the fashion of their time, the three young women in Woman with a Lute, A Lady Writing and Study of a Young Girl have shaved eyebrows and foreheads in common. Although highly fashionable, the use of cosmetics and beauty technology was criticized by conservative thinkers. In 1682, Utrecht schoolmaster Simon de Vries wrote, "Discomfort also goes with pride. This can be attested to by those who pull out the hair at the top of their forehead with little tongs or pincers in order to give this a broader appearance, or out of their eyebrows to make them thinner."

Portrait of a Lady

Rogier van der Weyden

c. 1460

Oil on panel, 34 x 25.5 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington D. C.

Hair removal was not a new concept. Hairlessness was seen as pure and innocent; after all, what else is as pure and innocent and hairless as a baby?

There is evidence supporting the use of hair removal practices as far back as ancient Egypt, Rome, and India, with razors made of shells and sugar-based waxes being used much like today. In Rome, having less body hair was believed to be a symbol of higher social standing. In medieval Europe, hair removal focused on the face, every effort was made to keep the largely concealed. Perhaps the most unique beauty trend to emerge from the period, however, was the desire for a large forehead. Fifteenth-century women often plucked or shaved their hairline back several inches. To complete the effect, they severely tweezed their eyebrows. The fashion for high foreheads continued through the 17th and 18th centuries, prompting women to raise their hairlines by at least one inch—the high forehead was considered a sign of intelligence. Preferred methods for hair removal included shaving, plucking, or applying a plaster of quicklime. After letting it dry, they would strip it off, taking the hair with it. Even eyebrows were often entirely plucked or waxed away, replaced higher up the forehead with fakes made of mouse skin.

Vermeer & Michael Sweerts

Clothing the Naked

Michael Sweerts

c. 1660–1661

Oil on canvas, 81.9 x 114.3 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Although Michael Sweerts was overlooked by contemporary chroniclers of painting, and his name and works were quickly forgotten upon his death, modern art scholarship has connected his achievements with Vermeer.

Sweerts spent several years in Rome, absorbing the lessons of Caravaggism, yet his works are never aggressive. His characters, captured in moments of reflection, possess a stillness, distance and melancholy that evoke some of Vermeer's finest works. He is also one of the few painters who depicted individuals from the lower classes with a dignity equal to that reserved for powerful upper-class portraiture. Like Vermeer, his diverse styles suggest different identities and have long confounded art historians.

From a formal perspective, Sweerts was consistently able to think in the broadest pictorial terms, eschewing the finicky, descriptive detail so popular in genre painting at the time. The monumentality of the figures and the pitch-black background in Clothing the Naked are reminiscent of Vermeer's Mistress and Maid, while the Young Boy with a Nosegay has often been speculated to be a direct inspiration for Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Earring. Sweerts' skill in capturing the sheen of fine, exotic silks with minimal effort would seem to have resonated with the serious Vermeer.

Strangely, Sweerts' own career is almost as obscure as Vermeer's, and little is known about his personal life. He began his career as a history painter but is most celebrated for his exquisite depictions of individual people.

Portrait or tronie?

Old Man in Oriental Garb

Jan Lievens

1628–1630

Oil on canvas, 135 x 101 cm.

Schloss Sanssouci, Berlin

Although to the modern eye the Study of a Young Woman would seem to be a portrait, a Dutch 17th-century observer would have immediately recognized it as a tronie, an defunct term referring to a type of picture popularized by Rembrandt and his followers. Some believe the genre was inspired by some of the grotesque heads drawn by Leonardo da Vinci.

Despite the fact that tronies were often highly individualized, they were most admired for the painter's ability to capture a specific psychological state or pictorial qualities. Most were based on living models, including the artists themselves, relatives or colleagues. However, they were not intended as formal portraits but were kept on hand in the artist's studio to pique the interest of potential buyers. An old man, a comely young woman, a "Turk," or a dashing soldier were all standard subjects for tronies. Artists favored garments that looked especially exotic, providing an opportunity to display their painting technique, one of the strongest credentials of a professional artist. Tronienem> also served as a repository of facial types and expressions for figures in history paintings.

Judging by the number of tronies mentioned in inventories, this was an extremely popular genre that catered to the interests of both the artist and the client.

Listen to period music

Antonio Vivaldi

Concerto for Flute and Strings op. 10, no. 3 RV 428 "Il Gardellino," Cantabile [1.02 MB]

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Vivaldi-8-Flute-Concertos/dp/B001LMF1ZK/ref=dm_cd_album_lnk?ie=UTF8&qid=1258623220&sr=1-3

Painting heads

Although the present picture has been historically overshadowed by its likely companion piece, The Girl with a Pearl Earring, it is nevertheless an expressive and technically refined, albeit understated, tour de force. The modeling of the young girl's face is so subtle that it is difficult to find a comparable image in Dutch painting of the period. The blurred, painterly modeling creates form by registering shifts in tone rather than by the sharp modeling favored by European history painters, in which line plays a significant role in defining each of the figure's features. A detail of the eye demonstrates how vague, yet utterly "sincere," is the description of the model's lunar physiognomy.

Vermeer employed a particularly limited palette for the depiction of flesh tones in the current work. By that time, the pigments needed to depict flesh—considered by art theorists to be the highest achievement of an artist—had been largely codified in "recipe" books, although variations did exist from nation to nation and from school to school. Wilem Beurs describes in his De Groote Waereld in 't Kleen Geschilder (1692) thirteen mixtures composed of nine pigments required to paint people of all different ages and genders as well as of distinct emotions.

Pictura (An Allegory of Painting) (detail)

Frans van Mieris

1661

Oil on copper, 5 x 3 1/2 in.

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angles

The detail of The Art of Painting by Frans van Mieris, painted about five years before Vermeer's work, illustrates the typically limited Dutch palette employed for depicting flesh. From top to bottom, we can discern white lead, yellow ocher, vermilion, red madder, raw sienna or red ocher (?), umber and black.

Although the pigments of Vermeer's faces have not been specifically analyzed, it appears that the artist used principally white lead, modified by a hint of vermilion—a bright red with a decidedly orange overtone—to depict the principal passages of the strongly illuminated areas, excluding the conventional yellow ocher. This simple mixture aligns well with the famous glowing milk-white complexions of Dutch women.

Precedents?

Margaret Lemon

Anthony van Dyck

c. 1638

Oil on canvas

59.5 × 49.5 cm.

Private collection, New York

Essentially nothing is known of the location of the Study of a Young Woman before 1829, when it was published in the Arenberg Collection catalogue. Nor do we know if it was inspired by another painting. Determining the origins and influences behind works of art, particularly from eras such as the 17th century, requires a multifaceted approach, blending historical research, stylistic scrutiny, and at times, scientific methods.

Woman with a Pink

Rembrandt van Rijn

Early 1660s

Oil on canvas, 92.1 x 74.6 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walter Liedtke suggested that the pose in this work, as well as in the smaller Washington panel, Girl with a Red Hat, mirrors the Renaissance style of presentation seen in Rembrandt's 1640 Self-Portrait and in several pieces by his disciples. A feminine rendition of this style is evident in Rembrandt's Woman with a Pink at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In this context, the subject's forearm leans on the frame rather than a cushion or ledge, and the hand, simplified to a mere wrist, showcases Vermeer's deliberate choice to prioritize visual perception over anatomical accuracy. The subtle flesh tones further amplify the facial impact, adding vitality to the composition.

However, it's essential to recognize that works of art, especially those with relaively simple compositions like Vermeer's Study of a Young Woman, might have emerged independently, separated by both time and distance. Thus, before claiming potential stylistic influences, it is crucial to first assess whether Vermeer could have feasibly accessed the artworks that art specialists beleive might have inspired him.