Christ in the House of Martha and Mary

c. 1654–1656Oil on canvas

160 x 142 cm. (63 x 55 7/8 in.)

National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

inv. 1670

The textual material contained in the Essential Vermeer Interactive Catalogue would fill a hefty-sized book, and is enhanced by more than 1,000 corollary images. In order to use the catalogue most advantageously:

1. Scroll your mouse over the painting to a point of particular interest. Relative information and images will slide into the box located to the right of the painting. To fix and scroll the slide-in information, single click on area of interest. To release the slide-in information, single-click the "dismiss" buttton and continue exploring.

2. To access Special Topics and Fact Sheet information and accessory images, single-click any list item. To release slide-in information, click on any list item and continue exploring.

The figure of Christ

Christ, due to the soft glow radiating from his head and his emphatic gesture, holds a dominant position in this piece. His pose aligns with the standard repertoire of 16th- and 17th-century Italian painting. Comparisons can be drawn with figures of Christ in works by Andrea Vaccaro (Naples, Pinacoteca Reggia di Capodimonte), Alessandro Allori (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum), or Bernardo Cavallino (National Museum, Naples). However, Dutchman Erasmus Quellinus' depiction of Christ is most often pointed to by art historians as the likely model for Vermeer's figure.

The question of where Vermeer encountered Quellinus' painting arises. Although lacking surviving documentation, it is proposed that Vermeer might have seen it in Antwerp during a study trip. Reynier Jansz., Vermeer's father, an art dealer with close ties to various painters, might have facilitated opportunities for his son to become acquainted with paintings and prints from numerous masters. Another Delft art dealer, Abraham de Coge, had significant interactions with Reynier during this period.

Through X-ray images, it's apparent that Christ's head was initially turned slightly away from its current position, and adjustments were made to the fingers of the left hand. While the composition and paint application of the earlier Diana and her Companions exhibit less competence compared to the Christ, the similarity in the drawing of the toes on the feet of Martha and Christ is noteworthy.

Mary meditating

No doubt, the most exquisite passage in this painting is that of the figure of Mary who gazes upwards at the seated Christ, awaiting his comfort and words of wisdom. Vermeer's sympathetic rendering of Mary, who in this context represents the contemplative life focused on the deeper meanings of life, may have struck a chord with the artist's own introspective nature.

Apart from the religious subject and the dramatic lighting, the proficient use of foreshortening of Mary's head suggests that Vermeer had likely trained with a classically oriented painter, although curiously there is no evidence of even passable foreshortening in his previous work, Diana and her Companions.

From a technical standpoint, foreshortening is the process of applying linear perspective to a single object, making it appear more or less compressed. It was one of the traditional skills required by any history painter. Foreshortening is particularly effective for enhancing the impression of three-dimensional volume and creating drama in a picture. Achieving the effect of foreshortening can be very challenging, especially when drawing complex anatomical features such as hands and the head. One of the most noted examples of foreshortening can be found in Mantegna's The Lamentation over the Dead Christ. At first glance, the painting seems to be a strikingly realistic study in foreshortening. However, careful scrutiny reveals that Mantegna reduced the size of the figure's feet so that they did not cover too much of the body. Vermeer employed foreshortening in a far less dramatic manner than that of Mantegna, but it is equally effective, enhancing the inquisitive glance of Mary.

The Lamentation over the Dead Christ

Andrea Mantegna

c. 1480

Tempera on canvas, 68 x 81 cm.

Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

A disappointed Martha

Although somewhat lacking in psychological depth, the rendering of the three biblical figures in Christ in the House of Martha and Mary demonstrates a reasonable grasp of anatomy and painting technique, which may have been the young artist's primary goal in such a demanding large-scale work. Instead of relying on direct observation, the artist appears to have utilized conventional techniques to convey Martha's attitude, such as her rhetorically raised eyebrows and pouting mouth. Her downcast gaze contrasts with the upheld head and hopeful gaze of Mary. The free-flowing brushwork of the women's headgear and the drastic simplification of the anatomical features betray an almost mannerist approach.

Some critics have noted a certain resemblance between the bust of the Milkmaid and this figure.

Painting technique: a basket of bread

This work evidences few of the stylistic concerns that would characterize Vermeer's mature work, one of which was the rendering of specific textures. The breadbasket of The Milkmaid (bottom), which was painted only a few years after Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, is rendered with obsessive attention to the knotty surface and intricate weave of the wicker basket. In this comparison, the basket held by Martha (top) is only summarily defined with a discreet number of elegant but complacent brushstrokes. The same shallow treatment is also reserved for the drapery of the figure of Christ and Martha. The folds are indicated with free-flowing, sloshy brushstrokes that fail to suggest either volume or an underlying substance, as if the painter was focused on the pleasure of painting rather than the object he is portraying..

A "Turkish" rug

The Oriental rug that appears in Christ in the House of Martha and Mary seems almost identical to the one represented in A Maid Asleep painted a few years later. Although they have in common a broad, light orange border ending in a fringe, the medallion in the former is yellow, in the latter green. It is likely that Vermeer used one rug as a model and painted imaginary variations on it. Such items were referred to as "Turkish rugs" in 17th-century Netherlands.

Observing the rather uninspired facture of this passage, the texture, detail and luminosity of the carpet in the later Music Lesson is almost unimaginable.

Uncertainty

The open hallway was a common feature of Dutch and Flemish kitchen scenes from which the present composition is derived. In any case, it enhances the three-dimensional recession of the otherwise ill-defined space. Vermeer expert Gregor Weber examined the problem so. "In Vermeer’s work, Christ and Martha are placed in front of a wall, with the back of Christ’s chair apparently close to it. Although difficult to read and unconvincing in its effect, the lighter and darker passages of this wall probably indicate a sequence of two parallel walls joined by one receding at right angles. Otherwise, there would be virtually no room for Martha to stand behind the table. An X-radiograph of the painting... shows a light vertical line behind Martha’s left shoulder proper (parallel to the seam joining two pieces of canvas). Could this line have indicated a lit edge, possibly of a similar post or corner of the wall that Vermeer later painted out?

Christ in the House of Mary and Martha

Christiaen van Couwenbergh

1629

Oil on canvas, 121 × 147.5 cm.

Musée d’Arts de Nantes, Nantes

The X-radiograph does not help to clarify the enigmatic structure of the narrow corridor on the left, which compositionally corresponds with the opening towards the kitchen in a work by the painter Van Couwenbergh. In Vermeer’s picture, its far end is marked by a double door, with its right wing open. To the right of this door is an opening into another room or alcove from which an amorphous orange shape (a billowing curtain?) protrudes. The left wall is pierced by two ambiguous openings. At the back is what appears to be a tall window, the top shutter open – or do the two small highlights underneath indicate steps leading to a door? Behind Mary, there is another puzzling structure, most likely a closed door or, possibly a recess in the wall, with integrated shelves. These uncertainties demonstrate Vermeer’s struggles to construct a convincing spatial continuum. It collapses entirely behind Mary’s stool, where the floor seamlessly continues into the wall. It is perhaps telling that after this unsatisfactory experience, Vermeer always chose simple, box-shaped spaces.

The background

The abbreviated, monochromatic treatment of the architectural features is typical of Italian religious painting, which focused the viewer's attention on the deeds and expressions of the figures rather than on the environment where the action unfolds. However, as Walter Liedtke pointed out, the "strong recession into a narrow space, where a window, ceiling beams and another door are visible, comes much closer to arrangements found in tavern interiors painted by the Rotterdam artist Ludolf de Jongh in the early 1650s, which were being adopted by Pieter de Hooch at about the same time."

Christ in the House of Mary and Martha

Christiaen van Couwenbergh

1629

Oil on canvas, 121 × 147.5 cm.

Musée d’Arts de Nantes, Nantes

Gregor Weber, however, has investigated the problem of the background in greater detail. He posits that the wall's shading suggests two parallel walls with another receding at a right angle. This arrangement is reminiscent of the rear wall in Van Couwenbergh's artwork, distinguished by a wooden post behind Christ. An X-radiograph of Vermeer's painting reveals a light vertical line behind Martha, suggesting a possible alteration by Vermeer. The painting includes a mysterious structure to the left, similar to an opening in Van Couwenbergh’s piece. This structure in Vermeer’s work comprises a double door and an ambiguous orange shape, potentially a curtain. The left wall has two unclear openings: one seemingly a window and the other possibly a door or stairs leading to a door. Behind Mary, there's another uncertain structure which might be a closed door or a recess with shelves. These features indicate Vermeer’s challenges in creating a believable spatial design, especially evident where Mary's stool meets the floor, merging it with the wall. After this, Vermeer typically opted for simpler spaces, primarily showing two walls without ceilings. Only in A Maid Asleep and The Love Letter does he offer views into adjacent rooms.

Christ's robe

The complacent rendering of Christ's robe strikes an unusual note in the artist's oeuvre, especially when compared to the drapery of the earlier Diana and her Companions, whose structure, while hardly expertly handled, is rendered with sincerity. Moreover, the artist employed two common and inexpensive pigments, smalt and indigo, to render its deep blue color instead of his trademark ultramarine blue found in almost every blue garment of the artist's oeuvre.

A see-through doorway

The Mother

Pieter de Hooch

c. 1661-1663

Oil on canvas, 92 x 100 cm.

Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

The dark recess behind the standing Martha to the left hides a corridor and a half-opened door. Painted with a narrow range of brown paint, the recess helps alleviate the presence of the three figures that flood up the composition's foreground, leaving a point of escape for the viewer called doorsien (see-through), a device recommended for this purpose by period art manuals. The doorsien was a prominent feature in Netherlandish kitchen scenes and was later exploited more subtly in the modern domestic settings by Vermeer's close colleague, Pieter de Hooch, as an open doorway, or doorkijkje.

A doorkijkje is a term used in Dutch art to refer to a compositional device where a scene is framed through an open doorway or window, allowing the viewer to glimpse into another space beyond. This technique creates a sense of depth and spatial continuity in the painting, drawing the viewer's attention into the distance and adding a layer of complexity to the composition. Doorkijkjes were often employed in Dutch interior paintings to enhance the sense of perspective and provide a visual pathway for the eye to follow.

special topics

- The painting's story

- The young Vermeer borrows

- Vermeer's Catholic ties

- Flemish inspiration

- Catholics vs. Protestants: The same story but two different interpretations

- The kitchen

- Biblical subjects

- Christ's chair

- unifying theme & composition

- Controlling the eye: The circular composition

- The influence of Hendrick ter Brugghen

- Painting ancient costumes

- Listen to period music

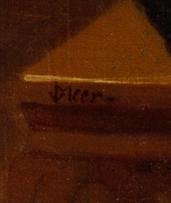

The signature

inscribed lower left, on bench: IVMeer (IVM in ligature)

(Click here to access a complete study of Vermeer's signatures.)

Dates

1654–1656

Albert Blankert, Vermeer: 1632–1675, 1975

c. 1655

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. The Public and the Private in the Age of Vermeer, London, 1997

c. 1654–1655

Walter Liedtke Vermeer: The Complete Paintings, New York, 2008

c. 1654–1655

Wayne Franits, Vermeer, 2015

c. 1654–1655

Pieter Roelofs & Gregor Weber, VERMEER, Amsterdam, 2023

(Click here to access a complete study of the dates of Vermeer's paintings).

Technical report

The painting's support is a fine, plain-woven eave linen with a thread count of 12 x 17 per cm². A vertical seam aligns with Christ's elbow. The canvas has been paste-lined and the original tacking edges have been removed. The double ground comprises a layer of white chalk bound with a protein medium followed by a red earth layer. In the background and in the shadowed flesh tones of Christ and Martha, the red ground is only partially covered by very thin brown glazes. What seems to have been a glaze on Christ's violet tunic remains preserved only in the texture of the brushwork. The highlights on all the drapery are painted with impasto: on Christ's blue robe, painted with indigo, smalt and lead white, the brushstrokes are about 1 cm wide and indicate a square-tipped brush.

Numerous wet-in-wet touches include the details of Martha's waistband, the modeling of the headgear and the decoration on the carpet. The speed of execution and the fluidity of the paint are also evident in the splashy, broken edges of many forms, such as the upper edges of the table and Mary's profile.

Several alterations are noticeable: Christ's profile and ear, the fingers of His left hand and the edge of Martha's right sleeve. The edge of some forms significantly encroaches on adjacent areas, like the upper edge of Christ's robe overlapping his tunic. Mary's left hand appears to have been painted over Christ's blue robe.

: Johannes Vermeer (exh. cat., National Gallery of Art and Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis - Washington and The Hague, 1995, edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr.)

Provenance

- collection Abbot Family, Bristol, c. 1880; furniture and antiques dealer, Bristol, 1884, sold to a private party and bought back;

- Arthur Leslie Collie, London;

- [Forbes and Paterson, London, 1901, sold to Coats];

- William Allan Coats, Skelmorlie Castle, Dalskairth, Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland (1901–1926);

- his sons Thomas H. and J. A. Coats (1926–1927);

- 1927 donation by the Coats heirs to the National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh (inv. 1670).

Exhibitions

- London 1929

Exhibition of Dutch Art, 1450–1900

Royal Academy of Arts

147, no. 310 - Amsterdam, October 21–November 3, 1935

Vermeer tentoonstelling ter herdenking van de plechtige opening van het Rijksmuseum op 13 juli 1885

Rijksmuseum

26–27, no. 162 and ill. 162 - Rotterdam July 9–October 9, 1935

Vermeer, oorsprong en invloed. Fabritius, de Hooch, de Witte

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

34, no. 79 and ill. 59 - Utrecht June 15–August 3, 1952

Caravaggio en de Nederlanden

Centraal Museum

57–58, no. 92 and ill. 71 - Edinburgh 1992

Dutch Art and Scotland: A Reflection of Taste

National Gallery of Scotland

150–151, no. 71 and ill. - Washington D.C. November 12, 1995–February 11, 1996

Johannes Vermeer

90–95, no. 2 and ill. - The Hague March 1–June 2, 1996

Johannes Vermeer

Mauritshuis

90–95, no. 2 and ill. - New York March 8–May 27, 2001

Vermeer and the Delft School

Metropolitan Museum of Art

no. 65 and ill. - London June 20–September 16, 2001

Vermeer and the Delft School

National Gallery

no. 65 and ill - Tokyo August 2–December 14, 2008

Vermeer and the Delft Style

Metropolitan Art Museum

164–166, no. 25 and ill. - The Hague May 12–August 22, 2010

The Young Vermeer

Mauritshuis

26–29, no. 1 and ill. - Dresden September 3–December 28, 2010

The Young Vermeer

Old Masters Picture Gallery

30–35, no. 2 and ill. - Edinburgh December 8, 2010–February 2011

The Young Vermeer

National Gallery of Scotland

30–35, no. 2 and ill. - Rimini January 21–June 3, 2012

Da Vermeer a Kandinsky

Castel Sismondo

76 and ill. - San Francisco March 7–May 3, 2015

Botticelli to Braque: Masterpieces from the National Galleries of Scotland

M. H. de Young Memorial Museum

52, no. 15 and ill. 53 - Fort Worth (TX) June 28–September 20, 2015

Botticelli to Braque: Masterpieces from the National Galleries of Scotland

Kimbell Art Museum - Sydney October 24, 2015–February 14, 2016

The Greats: Masterpieces from the National Galleries of Scotland

The Art Gallery of New South Wales

62, no. 13 and ill. - Tokyo October 5, 2018 –February 3, 2019

Making the Difference : Vermeer and Dutch Art

Ueno Royal Museum - Amsterdam February 10– June 4, 2023

VERMEER

Rijksmuseum

no. 1 and ill.

(Click here to access a complete, sortable list of the exhibitions of Vermeer's paintings).

The painting's meaning

Mary and Martha are the most familiar set of sisters in the Bible. Both Luke and John describe them as friends of Jesus. Luke's story, though only four verses long, has been a source of interpretation and debate for centuries.

Jesus, Mary and Martha

Anton L.J. Dorph

1880

Lithograph, 28 x 20 in.

While preaching to the people, Jesus Christ arrived in Bethany, a town situated not far from Jerusalem beyond the Mount of Olives, where a woman named Martha welcomed him into her home. Martha had a sister named Mary, who sat at the Lord's feet and listened to what he was saying. However, Martha was distracted by her many tasks, so she came to him and asked, "Lord, do you not care that my sister has left me to do all the work by myself? Tell her then to help me." Yet the Lord answered her, "Martha, Martha, you are worried and distracted by many things; there is need of only one thing. Mary has chosen the better part, which will not be taken away from her" (Luke 10:38-42).

This subject was more popular among Flemish than Dutch artists, possibly owing to its religious connotations. In the religious context of the time, the scene illustrated one of the fundamental differences between Catholics and Protestants: the latter sought salvation in action while the former placed greater value on contemplative life.

The young Vermeer borrows

Whereas harsh environmental conditions made travel in many European countries problematic, the level plains of the Netherlands were crossed by an extensive and well-cared-for network of canals that had been dug to regulate the flow of water. These canals also provided an extraordinarily practical means of heavy transportation, faster than any mode of transportation on land. Dutch trade, which had originally been based on spices, textiles and tulip bulbs, gradually extended to include paintings. The fact that Dutch paintings were small and easy to handle made them convenient for the market.

Visit in an Artist's Atelier

Job Adriaensz Berckheyde

1659

Oil on wood

State Hermitage, St. Petersburg

These conditions, along with widespread economic prosperity, favored the explosion of the Dutch art market. In an astonishingly short period, the Netherlands produced artists of the stature of Rembrandt, Vermeer, Frans Hals, Jan Steen, Jacob van Ruisdael and Pieter de Hooch. These artists were part of the same guilds, worked in the same commercial marketplace and were familiar with each other's work, often through prints. They competed, taught one another, collected each other's work and occasionally even collaborated.

Vermeer's art drew much from this dynamic artistic scene. He borrowed from every available source, ranging from the great masters of the Italian Renaissance to his fellow painters who lived just steps away from his studio.

Except for the artist-artisans, the intention of the artist, of course, was to create a work that would transcend its antecedents. The early 17th-century art theorist Karel van Mander advises as much and records a saying probably well known among painters of that era: "Well-cooked turnips make delicious soup’. This proverb contains a witty double entendre lost upon English speakers: the plural for "turnips" in Dutch is rapen, a word also meanings "to borrow" or "to steal."’ Critics believe that a significant portion of Vermeer's body of work is based on themes and compositions pioneered by his colleagues. However, he was one of those rare artists who could see great potential in the works of less talented artists. He had the unique ability to infuse new life and moral depth into common motifs, elevating them beyond their conventional interpretations.

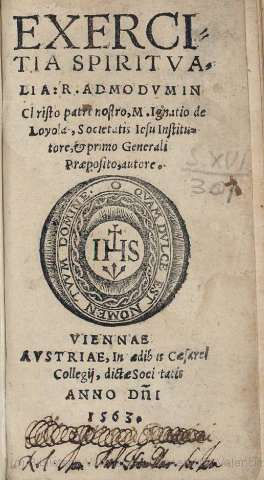

Vermeer's Catholic ties

Exercitia spiritualia (Spiritual Exercises)

of Ignatius of Loyola 1548

First Edition by Antonio Bladio (Rome)

Due to its atypical dimensions, it's probable that this artwork was specially commissioned. The lower perspective, even if not uniformly executed, suggests it was intended to be positioned at a significant height, perhaps above a fireplace.

Potential locations for its display might have been the secretive Jesuit church, the nearby Catholic girls' school on Oude Langendijk adjacent to Maria Thins’s residence, or it could have been for a private client, possibly living in the area known as Papenhoek (Papists’ Corner) in Delft. Although rejected by modern scholars, it was once believed that Vermeer had apprenticed with Leonaert Bramer, a Catholic and close friend to the Vermeer family in Delft. Bramer was the most prestigious figure in Delft painting at the time and was known to have traveled to Italy.

Particularly revealing is the elder artist's intercession on behalf of the young painter in his betrothal to Catharina Bolnes, the daughter of the well-to-do Delft patrician, Maria Thins. Bramer may have sealed the bargain by guaranteeing the young painter's future and a quick conversion to Catholicism, a rare event in 17th-century Netherlands. Just the same, no records have survived that mention Vermeer's apprenticeship, and his first works have almost nothing in common with Bramer's. In any case, it has been hypothesized that Vermeer's Christ is a tangible sign of his classical training combined with newfound Catholic sentiments, although the picture may have been commissioned by someone particularly interested in the theme. Martha and Mary represented two opposing personalities: the active and the contemplative. Christ's defense of the contemplative life suited Jesuit ideals and was contained within the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola. Vermeer's treatment of this subject, which focuses on the message that Christ is transmitting, may reflect his sympathetic response to the Catholic Church in the mid-1650s. Vermeer's mother-in-law, Maria Thins, maintained close contacts with the Jesuits in Delft.

Flemish inspiration

Christ in the House of Martha and Mary

Erasmus Quellinus

c. 1645

Oil on canvas, 175 x 243 cm.

Musée des Beaux Arts, Valenciennes

In no other painting did Vermeer focus so exclusively on the figures. Within a few years, however, he dramatically changed his artistic course and became absorbed in the relationship of the figure to the environment, rather than with the figures themselves.

The inspiration for Vermeer's "Christ in the House of Martha and Mary" is believed to have come from a variety of sources, including both artistic and cultural influences of his time. While there is no definitive record of the exact sources Vermeer drew from, art historians have identified potential inspirations that may have contributed to the composition and themes of the painting. The most likely model was a work by the Fleming Erasmus Quellinus (Musée des Beaux Arts, Valenciennes), one of Ruben's most successful assistants. Vermeer must have seen it. The art historian Wayne Franits points out that "Quellinus's artwork bears resemblances to Vermeer's in various aspects, including motifs such as the open door in the background and the pose of Christ with Mary at his feet. The portrayal of Christ's figure also draws on prototypes from Italian art. The sensitivity to light in Quellinus's painting, particularly its cool effects, evokes the style of artworks created in the 1620s by the Utrecht Caravaggisti, Dutch painters associated with Utrecht (a city where Vermeer might have received training). These artists were followers of the renowned Italian master Caravaggio. However, the subtle use of light and shadow in Quellinus's painting, as well as the treatment of the table covering, foreshadow later developments in Vermeer's own artistic approach."

In his work, Quellinus treats the female figures as attendant saints, positioning them at respectful distances, whereas Vermeer brings the women closer to Christ and conveys their response to his words through their poses and expressions. In Christ's flowing drapery, refined face and elegant hands, as well as in the balanced arrangement of the figures, Vermeer appears to have adopted the polished style of Van Dyck's religious paintings. However, the essence of the subject is conveyed much like in works by Rembrandt and his most accomplished followers. Martha's expression, for instance, evokes the wounded young woman depicted in Nicolaes Maes's 1653 painting, Abraham Dismissing Hagar and Ishmael.

The kitchen

Kitchen Scene with Christ in

the House of Martha and Mary

Diego Velásquez

Oil on canvas, 63 x 103.5 cm.

National Gallery, London

In northern Europe, but not only, the Christ's visit to Martha and Mary motif had inspired many paintings that were in essence only barely veiled still-lives. The most illustrious southern European example is the version by Diego Velásquez. Here, the Spanish master lavished great attention on the two bodegones figures in the foreground and on the kitchen utensils and food, perhaps drawn from the artist's own living conditions. Relegated to a secondary role, the religious scene takes place in what appears to be a see-through window of a rustic kitchen which, however, can almost be mistaken for a framed picture.

Dutch and Flemish painters had forged an autonomous genre that garnered widespread admiration and collectors' attention due to its inventiveness, technical brilliance and remarkable prowess in capturing the diverse textures and colors of foodstuffs, combining elements of still life, genre painting and portraiture. These works often depicted busy households engaged in various culinary activities, from food preparation to dining and camaraderie. The compositions were meticulously arranged, featuring an array of utensils, foodstuffs and kitchenware, all carefully rendered with a keen eye for realism.

However, the kitchen scenes weren't just about portraying the mundane aspects of daily life; they were also imbued with symbolic and allegorical meanings, alluding to themes of abundance, frugality, the passage of time and the transience of life. Such symbolic elements added layers of meaning to these seemingly straightforward depictions of kitchens and interiors.

Closer to home, Pieter De Bloot's version of the theme shows a sprawling kitchen scene that undoubtedly reflected the Dutch preoccupation with household chores and domestic virtue rather than an explicit commitment to spiritual matters.

The Four Elements: Fire (detail)

Joachim Beuckelaer

1570

Oil on canvas, 157.5 x 215.5 cm.

National Gallery, London

One of the most extraordinary renditions of the Christ in the House of Martha and Mary theme is Joachim Beuckelaer's Fire, one work of a set of four pictures which take as their themes the four elements of Earth, Water, Air and Fire. In each, seductive representations of market produce for sale or for cooking are combined with biblical episodes. In Fire, modern viewers are puzzled by the importance given to the worldly kitchen scene with respect to the tiny biblical scene relegated to the furthest point of the painting's complex spatial construction. Beuckelaer consigns the teaching of the divine word to the back of the painting, devoting the entire foreground to active life.

Women are frequently the central figures in these scenes, reflecting their roles as caregivers and homemakers. However, these paintings might also contain subtle social commentaries, highlighting the virtues of domesticity or, conversely, the perils of idleness and gossip.

Many objects in Netherlandish kitchen scenes have symbolic meanings. For example, a peeled lemon might hint at the bitterness of life, while oysters could allude to transience or even be a sensual reference. One of the most striking aspects of Netherlandish kitchen scenes is the artists' meticulous attention to detail. From the textures of foods to the gleam of copper pans, these paintings capture a remarkable sense of realism. Some kitchen scenes, however, served as cautionary tales, showing the dangers of gluttony, the consequences of idleness or the perils of lust.

Biblical subject matter

Bathsheba

Jacob van Loo

c.1650

Oil on canvas, 81 x 68 cm.

Musée du Musée du Louvre, Paris

The motivation behind the young Vermeer's choice of blantanly religious subject matter such as Christ in the House of Martha and Mary is shrouded in uncertainty, possibly stemming from a deeply personal religious conviction. Alternatively, it is plausible that the picture was commissioned by a Jesuit patron, potentially facilitated through Maria Thins—Vermeer's mother-in-law—who maintained strong ties with Delft's entrenched Catholic circles. Notably, Thins seems to have provided sustenance for the painter and his family throughout his artistic journey.

Other than the presnt painting and, perhaps, the Saint Praxedis, Vermeer painted at least one other painting with Biblical subject matter, a so-titled The Visit to the Tomb, which ppeared in the 1657 inventory list of Amsterdam art merchant Johannes de Renialme, indicating it was produced that year or earlier. Unfortunately, this painting has since been lost, with no known descriptions or visual evidence of its existence. Gregor Weber posits that while it's believed the painting portrayed the discovery of Christ's empty tomb on Easter, it is uncertain which biblical account Vermeer was inspired by—the more dynamic description in the Gospel of Saint Matthew (28:1–6) or the subdued retellings by Saint Mark (16:1–6), Saint Luke (24:1–6), and Saint John (20:2–20)—it's plausible that the artist was inclined towards the latter, more commonly depicted narrative.

Although the Bible had been one of the most important sources of inspiration for European painters, by the mid-17th century, still life, portraiture, landscape and interiors had largely replaced traditional religious and historical subjects in the Netherlands. Just the same, contemporary art theorists still defended the intellectual and moral superiority of istoria, or history painting (see example left) and many of the most ambitious painters, like Rembrandt, devoted their energies to its mastery.

History painting offered uplifting or cautionary narratives that were intended to encourage contemplation of the meaning of life. It also satisfied a desire for religious imagery that remained strong, even after most traditional religious pictures had been removed from Calvinist churches in the wave of iconoclasts, which resulted in a loss of a great part of the early Dutch pictorial heritage.

For unknown reasons, Vermeer soon abandoned history painting and embraced the "modern" mode of painting practiced by celebrated artists like Gerrit ter Borch, Gerrit Dou and Frans van Mieris. Vermeer would only take up the religious motif again in the late Allegory of Faith, a full-fledged religious work set in a 17th-century domestic interior, a somewhat awkward combination of the two modes of painting, at least for modern sensibilities.

Unifying theme & composition

From the onset of his career, Vermeer was keenly aware of the expressive role of composition. To understand how effectively he employed composition in the present work, it is necessary to be familiar with the religious implications of the Christ in the house of Martha and Mary theme in 17th-century Netherlands.

In this famous biblical story, commentators had long recognized the contrast between the active life of Martha (who complains to Christ about her sister's lack of help in domestic chores) and Mary's contemplative nature (who passively attends to the words of Christ, neglecting Martha's call for help). The sisters had been traditionally identified as symbols of opposing paths of salvation. Martha represented the necessities of performing good works while Mary shunned earthly concerns and put all her faith in the message of eternal life promised by Christ. This story illustrates one of the central debates between the Protestant and Catholic cults.

For Protestant reformers, the story supported the belief that salvation can be obtained by adopting faith in the forgiveness of sin through a merciful God, earned by Christ's Crucifixion. Roman Catholics, on the other hand, emphasized salvation not only through faith in God but also through proper action. For the latter, salvation could be earned through acts of humility and good works. Although Christ did define Mary's contemplative role as the "better part," Catholics pointed out that Mary's faith would be incomplete without an active life.

By stressing certain elements of the composition or downplaying others and organizing the positions of each, an artist can manipulate the meaning of the parable in favor of one or the other point of view. It has been frequently remarked that Vermeer balanced the figures of Martha and Mary in the composition, giving equal compositional weight to each. On the picture plane, both touch Christ, and all three figures are bound in an imaginary circle, further enhancing their unity. Vermeer might have been aware of the conflict between the Protestant and Catholic positions and attempted a synthesis in his painting through a reconciliatory balance.

Controlling the eye: the circular composition

Christ in the House of Mary and Martha

Jacopo Tintoretto

c. 1580

Oil on canvas, 200 x 132 cm.

Alte Pinakothek, München

Even in his early works, Vermeer clearly demonstrated his ability to draw visual, technical and intellectual inspiration from a variety of sources and weave them together with originality. This work draws upon sources as diverse as Italian and Netherlandish painting.

Though hidden to the untrained eye, the three figures are bound in a circular composition (see Special Topic above), unifying theme and composition. Circular compositions were frequently employed to unite complex figure groupings and prevent the viewer's eye from straying aimlessly around the picture. Interestingly, Tintoretto's own Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, painted about 70 years earlier than Vermeer's version, presents a noticeable circular composition. However, if the implied circle becomes too influential, the observer may feel subliminally entrapped. As a remedy, Dutch artists often included a sort of escape route, termed a doorsien, such as the background scenes in Tintoretto's painting. Vermeer provided a similar visual relief in the half-opened doorway (in Dutch, "doorkijkje") to the dark recess of the upper left-hand corner of the composition.

The influence of Hendrick ter Brugghen

Saint Sebastian Tended by Irene and her Maid

Hendrick ter Brugghen

1625

Oil on canvas, 149 x 119.4 cm.

Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, Ohio

During his formative years, Vermeer explored a wide range of artistic possibilities and melded them with his innate sense of measure and moral seriousness.

One of the Dutch paintings related to Vermeer's Christ in the House of Martha and Mary is Hendrick ter Brugghen's Saint Sebastian Tended by Irene and her Maid, known for its tightly composed figures. The young Vermeer also found other aspects of Ter Brugghen's art intriguing, such as his control of light and the simplicity of his modeling. While the brushwork of the renowned Frans Hals and Rembrandt might more immediately captivate the eye, Ter Brugghen's manipulation of paint ranks among the most masterful in European easel painting, and this skill was recognized in his time. During a visit to Amsterdam, Peter Paul Rubens, the foremost painter in Europe, even stopped by Ter Brugghen's studio while passing Rembrandt's.

In Ter Brugghen's Saint Sebastian, form emerges through sweeping brushstrokes of vibrant paint. Only at this level of technique does painting feel like a natural activity. When Vermeer painted the head and headgear of the kneeling Mary, he might have aimed to imitate the compactness of the illuminated head in the central figure of Ter Brugghen's composition. He might have realized that only broad, robust brushwork could harmonize such a large-scale composition while conveying the gravity and stillness he was striving for.

Painting ancient costumes

Christ Washing the Disciples' Feet(detail)

Garofalo

c. 1520–1525

Oil on panel, 35.9 x 52.1 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Dress has always held a significant role in history painting and portraiture. A fundamental tenet of traditional history painting, such as Vermeer's present work, was the imperative to avoid contemporary dress at all costs. This was partly due to the recognition that most historical figures could be identified through traditional attire, and partly because the prevailing thought was that contemporary fashion inadequately conveyed the universal principles deemed the pinnacle goal of painting by art theorists.

However, there was no definitive consensus on the precise attire most suitable for history painting. Costume expert Marieke van Winkel noted that art theorists offered only broad guidelines for appropriate clothing (and even colors) for the main protagonists. For instance, kings of any era were expected to wear a medieval crown and an ermine cloak, while youth were to be clad in brightly colored garments. Nevertheless, despite the attempts of art theorists to guide artists' choices and encourage consultation of classical texts, each painter addressed the challenge of visualizing an unfamiliar past in their own unique manner. In practice, ancient texts provided scant details that could be practically applied, and even the Bible, a primary source of history painting subjects, remained silent on this matter.

In general, artists favored simple, loose costumes adorned with flowing drapery that eluded association with any specific time or place. Such attire allowed for painterly interpretation and inherently conveyed a sense of timelessness. While a painter might incorporate accessories from their collection, most drew upon their imagination or prints of old master paintings. Regardless, achieving a certain natural flow was an essential aspect of successfully depicting drapery.

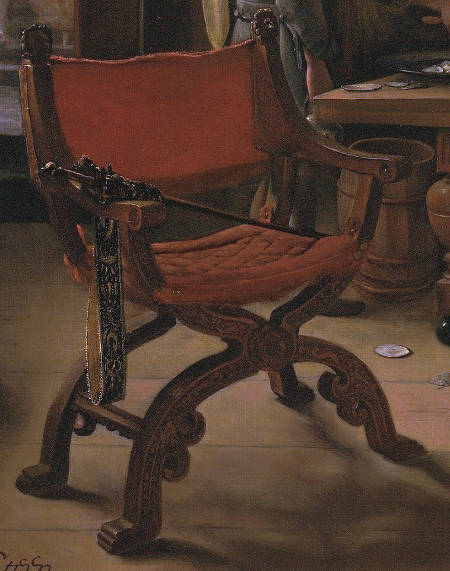

Christ's chair

The Artist Eating Oysters in an Interior (detail)

Jan Steen

c. 1660

Oil on canvas, 102.8 x 133.9 cm.

Private collection

Vermeer's robed Christ is depicted seated upon a customary, sturdy, x-framed armchair, a seat often reserved for figures of authority. Similar chairs can be found in paintings with comparable themes, as well as in various Dutch interior artworks. For numerous centuries, chairs held a symbolic significance of state and dignity, thereby absent from lower- or middle-class households. Ordinary individuals sat on basic three-legged stools, benches, or "barrel chairs," while chairs for children were nonexistent. During the Renaissance, chairs evolved into a standard piece of furniture accessible to those who could afford them. Toward the end of the 16th century, weighty oak armchairs, intended for the household head, gained popularity in the Netherlands. Subsequently, throughout the 17th century, an array of chair designs emerged, increasingly featuring upholstery composed of leather and luxurious fabrics.

Listen to period music

![]() Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach

Recitativo, Siehe, ich stehe vor der Tür (Behold, I stand at the door) (1.48 MB)

from cantata BWV 61 Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland

http://www.amazon.de/Kantaten-BWV-140–161-36/dp/B0000035PF/ref=sr_1_22?ie=UTF8&s=music&qid=1258281314&sr=1-22

Siehe, ich stehe vor der Tür und klopfe an.

So jemand meine Stimme hören wird und

die Tür auftun, zu dem werde ich eingehen

und das Abendmahl mit ihm halten

und er mit mir.

Behold, I stand at the door and knock.

If anyone hears My voice and

opens the door, I will come into him

and will dine with him,

and he with Me.

(Revelation 3,20; version American Standard Bible 1993)

Catholics vs. Protestants: he same story but two differnt interpretations

The story of Christ in the house of Martha and Mary can be found in the Gospel of Luke 10:38-42. In this passage, Jesus visits the home of Martha and Mary. While Martha busies herself with serving, Mary sits at Jesus' feet, listening to his teachings. When Martha complains that Mary isn't helping with the chores, Jesus responds that Mary has "chosen the better part."

The general interpretation of this passage in both Catholic and Protestant traditions is an affirmation of the importance of spiritual devotion over being overly concerned with worldly duties. However, the emphasis and nuances in interpreting this story can differ between the two traditions.

Catholic Interpretation:

Active vs. Contemplative Life: The Catholic tradition often uses this story to highlight the balance and tension between the active life (represented by Martha) and the contemplative life (represented by Mary). Both paths can lead to holiness, but the story suggests that the contemplative path holds a special place.

Veneration of Mary: In Catholicism, Mary, Martha's sister, is sometimes seen as a prototype of the Virgin Mary, representing pure contemplation of Christ. This association is not typically made in Protestant interpretations.

Sacramental Perspective: Some Catholic interpretations might link Martha's service to the sacramental life of the Church, where physical actions (like the sacraments) lead to spiritual grace. Yet, the story suggests that the spiritual (Mary's choice) should not be neglected for the sake of the physical (Martha's chores).

Protestant Interpretation:

Personal Relationship with Christ: Many Protestant interpretations emphasize the personal relationship with Jesus, as shown by Mary. Being in a direct, personal relationship with Jesus (by reading the Bible, praying, etc.) is valued over mere activity or service.

Caution against Works-Righteousness: Some Protestant traditions may use this story to caution against relying solely on "works" for salvation (represented by Martha's activities) and stress the importance of faith and grace (Mary sitting at Jesus' feet).

Universal Priesthood of Believers: Protestants often emphasize the direct access of all believers to Christ. In this context, Mary's direct approach to Jesus and her choice to learn from him can be seen as an affirmation of this belief.