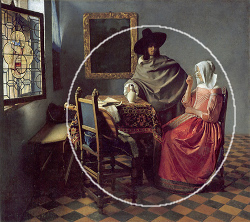

The Glass of Wine

(Het glas wijn)c. 1658–1661

Oil on canvas, 65 x 77 cm. (25 5/8 x 30 1/4 in.)

Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz,

Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

inv. 912C

The textual material contained in the Essential Vermeer Interactive Catalogue would fill a hefty-sized book, and is enhanced by more than 1,000 corollary images. In order to use the catalogue most advantageously:

1. Scroll your mouse over the painting to a point of particular interest. Relative information and images will slide into the box located to the right of the painting. To fix and scroll the slide-in information, single click on area of interest. To release the slide-in information, single-click the "dismiss" buttton and continue exploring.

2. To access Special Topics and Fact Sheet information and accessory images, single-click any list item. To release slide-in information, click on any list item and continue exploring.

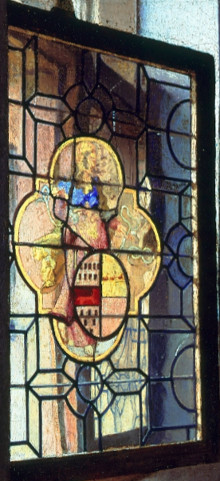

The stained-glass window

One of the most remarkable features of the painting is the colored stained-glass window, also depicted in Girl with a Wine Glass in Brunswick. The coat of arms is associated with Janetge Jacobsdr. Vogel, the first wife of Moses van Nederveen. Yet, how Vermeer obtained this emblem remains unclear. Vogel and her husband resided in Delft, relatively close to Vermeer. However, she passed away in 1624, eight years before the artist's birth.

According to traditional interpretation, the symbolism of the coat of arms is transparent and would have been easily comprehended in Vermeer's time. The female figure, holding a level and bridle, represents Temperantia or Temperance. This image bears a striking resemblance to a depiction in Gabriel Rollenhagen's Selectorum Emblematum from 1613. Accompanying Rollenhagen's illustration is the text: "The heart knows not how to observe moderation and applies reins to feelings when struck by desire." The level represents righteous actions, while the bridle signifies emotional restraint. It's likely that, paired with the solemn portrait on the opposite wall, this emblem served as a reminder of moderation—a cautionary note highlighting the central figures' apparent lack of discipline.

However, this interpretation has faced recent scrutiny from Dutch art expert Ariane van Suchtele and Huib J. Zuidervaart. Van Suchtele proposes that earlier observers misinterpreted the standing figure as embodying Temperance, assuming the item in her hand was a rein—a typical symbol of this cardinal virtue. In contrast, the woman in the window's central section holds not a rein, but the ornate straps of a coat of arms. The vibrant window bearing the elaborate family crest implies a lineage of sophistication, a trait seemingly at odds with the depicted youths.

Zuidervaart, instead, offers another theory suggesting that Vermeer's paintings The Glass of Wine and The Glass of Wine were commissioned as wedding gifts for the grandchildren of Moijses van Nederveen and Janetge de Vogel. Although there is no direct archival evidence supporting this theory, historical facts do not contradict it. The dating of the paintings aligns with the proposed scenario, and their origin and characteristics make sense within this context. The paintings feature a coat of arms, which can be explained in relation to the background of Vermeer's presumed client. Also that the presence of similar ceramic floor tiles in both paintings, differing from other Vermeer works, could be attributed to the mansion in front of the Nederveen-Van der Heul gunpowder factory, where the paintings might have been set up. This is further supported by the consistent lattice pattern in the window of the painting A Girl Interrupted in her Music, suggesting a third connection to the same location. Unlike the common belief that Vermeer's paintings were created in his studio, the author suggests that if Vermeer used optical equipment, it could be easily portable, similar to an optical projection device created by Johan van der Wyck in Delft in 1653.

Such variances in understanding Vermeer's ostensibly clear paintings remind us that, despite extensive research, the meanings behind Vermeer's pieces remain elusive. Subtle shifts in tone and significance remain subjects for further scrutiny.

The wooded landscape in the background

End of Village

Allart van Everdingen

Oil on canvas, 76 x 66.5 cm.

Szépmûvészeti Múzeum, Budapest

The intricately painted wooded landscape follows the stylistic tendencies of Allart van Everdingen, displaying a remarkable finesse. Allart van Everdingen, notable as the younger sibling of the artist Caesar van Everdingen, whose grandiose portrayal of Cupid makes multiple appearances in Vermeer's body of work, one of which was subsequently painted over. A similar picture-within-a-picture portraying a wooded lanscape also appears in the background Vermeer's later The Concert, perhaps with a similar symbolic function.

While Dutch art scholars have effectively showcased instances where figural paintings, maps and drawings concealed covert meanings within depicted scenes, landscapes primarily served as ornamental additions. Elise Goodman, instead, counters this notion, asserting that landscapes refers to Petrarchan lyrics which describe nature as the sympathetic witness to a wandering lovers' loneliness, and constitute "iconographically charged emblems that contribute to and expand on the meaning of the pictures." Consequently, the landscape in the current piece accentuates the amorous intent of the sophisticated cavalier, who communicates his affection through refined musical expression and wine consumption, in accordance with established norms of ritualized courtship. The practice of employing landscapes as metaphors for love finds frequent resonance in literature and popular love verses accompanied by music.

The opulent gilt frame significantly enhances the aesthetically opulent yet controlled delight of the composition.

The patient cavalier

With one hand resting on a wine jug and the other on his hip, the cavalier exhibits patient anticipation, poised to receive a refill from the elegantly attired young woman, ready to replenish his wine as soon as it is consumed.

While small rivers of ink have been expended to unravel the sentiments of Vermeer's female subjects, comparatively scant attention has been paid to the gentlemen who court them. In Vermeer's canvases, it is consistently the female figures who, ultimately, hold sway over the composition, relegating the male personas to an intriguingly passive disposition.

The gentleman depicted in this artwork would not have run afoul of decorum by retaining his hat. As noted by historian Timothy Brooks, during the era when this painting was crafted, "a courting man did not go hatless. The custom of removing one's hat while entering a building or greeting a woman was not yet observed. Europeans only bared their heads before a monarch, and since the Dutch had no monarchs, their hats stayed on."

Marieke de Winkel, an authority on Dutch attire in the context of art, has extensively examined the relationship between clothing and painting. She observed that in 17th-century Netherlands, "the hat was perceived as a sign of authority and male supremacy. In contemporary French and Dutch language, the word 'hat' could be used as a metaphor for a man, as opposed to 'coif,' denoting a woman. German and English travelers in the Netherlands were frequently taken aback by the fact that Dutch men retained their hats indoors, during meals, in social gatherings and even within places of worship. Individuals from the lower strata of society were expected to doff their hats in the presence of superiors. Outsiders often interpreted the Dutch nonchalance toward 'hat honor' as emblematic of their yearning for egalitarianism, personal autonomy and liberty."

The young girl's red tabbaard

Before Vermeer settled upon the elegant fur-trimmed yellow morning jacket for his female subjects, it appears that he initially gravitated toward a more formally designed full-length dress. Dutch attire authority Marieke de Winkel identifies this attire as a tabbaard, which comprises a stiffened bodice coupled with a coordinated skirt. The term itself originates from the Dutch language and referred to a particular type of ensemble that combined a structured bodice with a matching skirt. This garment was characterized by its closed back and heavily boned construction, which contributed to its rigid and well-defined shape. The tabbaard was often worn for formal occasions, as its structured design and boning created an elegant and polished silhouette.

Before Vermeer settled upon the elegant fur-trimmed yellow morning jacket for his female subjects, it appears that he initially gravitated toward a more formally designed full-length dress. Dutch attire authority Marieke de Winkel identifies this attire as a tabbaard, which comprises a stiffened bodice coupled with a coordinated skirt. The term itself originates from the Dutch language and referred to a particular type of ensemble that combined a structured bodice with a matching skirt. This garment was characterized by its closed back and heavily boned construction, which contributed to its rigid and well-defined shape. The tabbaard was often worn for formal occasions, as its structured design and boning created an elegant and polished silhouette.

The bodice of the tabbaard was designed to fit closely to the body, providing support and shaping to the torso. It was typically stiffened with boning, which could be made from materials like reeds, baleen or whalebone. This boning helped maintain the bodice's shape and structure, while also accentuating the wearer's figure. The skirt of the tabbaard would match the bodice in fabric and color, creating a cohesive and coordinated look. One of the distinctive features of the tabbaard was its closed back. Unlike some other styles of dresses that featured lacing or fastenings at the back, the tabbaard had a fully enclosed back panel. This added to the dress's formal and refined appearance. The closed back also contributed to the overall stiffness of the dress, enhancing its structured aesthetic but inflicting no little paint upon the woman who wore it..

The selection of this striking red satin gown, adorned with shimmering gold brocade of Vermeer's picture, intimates that the young woman harbored lofty expectations for her rendezvous with the sophisticated gentleman, thereby adorning herself to create a lasting impression.

In order to capture the remarkable shade of red that enlivens the cool blues and grays within the composition, the dress was initially painted using vermilion—the sole vivid, opaque red accessible to painters of the 17th century. As per a well-established formula, subsequent to thorough drying, the area was meticulously glazed with a fine, translucent coat of red madder, diluted with natural dyed oil. This technique lends the vermilion a stained-glass depth that could not be achieved through a direct blend of the two pigments.

The girl's white cap

The elegantly attired young lady delicately savors the final remnants of her wine, adeptly gripping the glass by its stem as dictated by the guidelines in etiquette manuals of the era. Her countenance remains veiled, with her left arm positioned squarely against her body—an act that appears to shield her from the discreet advances of her admirer.

A similar white cap worn by the young woman finds itself recurrently featured in various of Vermeer's compositions, as well as within numerous genre paintings from the same period. This cap is seen both secured and loosely fastened. Marieke de Winkel, an esteemed authority on Dutch attire, elucidates that these caps bore a dual purpose. While they held an ornamental role, they also served a practical function, safeguarding the wearer's hairstyle before and after dressing. In the inventory of Vermeer's wife, Catharina Bolnes, three such caps were meticulously cataloged as "drye witte kappen," although in Delft, this form of headgear was also referred to as a "hooftdoek." It was commonly donned during informal occasions and was typically crafted from white linen, occasionally from nettlecloth or cotton.

The ceramic tiled floor

Vermeer was not the first painter to incorporate tiled marble floors into his interior compositions. Such floors can be found in a plethora of depictions of the so-called "merry companies," a popular subject among artists like Anthonie Palamedesz, who embraced this motif over two decades prior. However, Pieter de Hooch, who operated in Delft and likely shared a close artistic rapport with Vermeer, stands as the pioneering artist to systematically integrate them within a coherent framework of linear perspective. His evocative box-like spatial arrangements may have served as the foundation for four of Vermeer's earlier interior works.

This type of expedited yet methodical perspective creates an awe-inspiring sensation of space and allows the figures and furnishings within the painting to assume a steadfast and precise connection with the floor. Even though the majority of Dutch floors were fashioned from large wooden planks, as seen in many interior scenes by Vermeer's competitor Gerrit ter Borch—a choice more suited for the chilly Dutch winters—tiled floors became a customary feature of Dutch genre painting.

Within this painting, Vermeer depicts relatively economical ceramic tiles, which were of a smaller size and significantly more prevalent compared to the grand black and white marble floors that would recurrently grace his interior compositions. Upon close scrutiny, subtle irregularities and chips become evident—quaint narrative details that would be eradicated in Vermeer's later creations. Ceramic tiles offered the advantage of being significantly more affordable than marble tiles, yet they came with the drawback of being relatively susceptible to chipping, as evidenced by some of the tiles within this painting.

During the 17th century in the Netherlands, crafting ceramic tiles for flooring was an artistry that blended practicality with decoration. This multistep process began with clay selection and preparation, combining different clay types for durability and color stability. Shaping the clay into uniform tiles followed, achieved through hand-molding, molding with intricate designs, or extrusion. Decorative techniques included impressing patterns, using liquid clay for contrasting hues and employing stencils to create geometric or nature-inspired designs.

After thorough drying to prevent cracking, firing took place in kilns, turning the clay into robust material. Glazing, an optional step, provided a glossy finish and protection from wear and fading. Tiles were then arranged to form interesting patterns on the floor. Installation involved embedding the tiles in mortar or adhesive with precise alignment.

The ceramic tiled floor

Vermeer was not the first painter to incorporate tiled marble floors into his interior compositions. Such floors can be found in a plethora of depictions of the so-called "merry companies," a popular subject among artists like Anthonie Palamedesz, who embraced this motif over two decades prior. However, Pieter de Hooch, who operated in Delft and likely shared a close artistic rapport with Vermeer, stands as the pioneering artist to systematically integrate them within a coherent framework of linear perspective. His evocative box-like spatial arrangements may have served as the foundation for four of Vermeer's earlier interior works.

This type of expedited yet methodical perspective creates an awe-inspiring sensation of space and allows the figures and furnishings within the painting to assume a steadfast and precise connection with the floor. Even though the majority of Dutch floors were fashioned from large wooden planks, as seen in many interior scenes by Vermeer's competitor Gerrit ter Borch—a choice more suited for the chilly Dutch winters—tiled floors became a customary feature of Dutch genre painting.

Within this artwork, Vermeer depicts relatively economical ceramic tiles, which were of a smaller size and significantly more prevalent compared to the grand black and white marble floors that would recurrently grace his interior compositions. Upon close scrutiny, subtle irregularities and chips become evident—quaint narrative details that would be eradicated in Vermeer's later creations. Ceramic tiles offered the advantage of being significantly more affordable than marble tiles, yet they came with the drawback of being relatively susceptible to chipping, as evidenced by some of the tiles within this painting.

During the 17th century in the Netherlands, crafting ceramic tiles for flooring was an artistry that blended practicality with decoration. This multistep process began with clay selection and preparation, combining different clay types for durability and color stability. Shaping the clay into uniform tiles followed, achieved through hand-molding, molding with intricate designs, or extrusion. Decorative techniques included impressing patterns, using liquid clay for contrasting hues and employing stencils to create geometric or nature-inspired designs.

After thorough drying to prevent cracking, firing took place in kilns, turning the clay into robust material. Glazing, an optional step, provided a glossy finish and protection from wear and fading. Tiles were then arranged to form intereting patterns on the floor. Installation involved embedding the tiles in mortar or adhesive with precise alignment.

The ceramic wine jug

The Music Lesson (detail)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 73.3 x 64.5 cm.

The Royal Collection, The Windsor Castle

With his right hand the courting gentleman grasps the white wine jug, which is, perhaps, literally and figuratively the heart of the scene. This type of all-white tin-glazed containers appears in the present painting was originally produced in Faenza, Italy. In the 1550s, they were exported to all over Europe and by the late 16th and early 17th century had become very fashionable. Vermeer must have been very fond of this type of wine jug since it appears in strategically important areas in three other compositions (see detail of the Music Lesson).

In Holland, such containers were imitated by local potters and became a favorite subject of a great many genre interior painters between 1650 and 1670. Although it is very difficult to distinguish between Italian and Dutch versions, historian of the Dutch decorative arts Alexandra Gaba-van Dongen believes that the ones in Vermeer's paintings are original Italian.

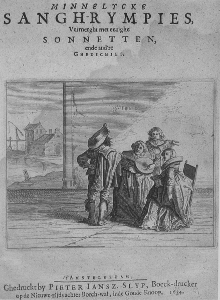

Music, love and Petrachan poetry

Title page from

Jan Hermanz. Krul

Minnelycke sang-rympies

Engraving, National Gallery, Washington, D.C.

Art scholars have increasingly concluded that Vermeer's paintings often contain subtle references to music, a prevailing metaphor in the 17th century representing love and harmony within familial, romantic, or social relationships. During this era, love songs were prominently featured in numerous 17th-century songbooks, as musical gatherings provided rare opportunities for social interaction among individuals of elevated social standing.

Elise Goodman, a respected art historian, underscores that the couple depicted in this painting belongs to the haute bourgeoisie—individuals who were adept in reading, writing and often conversing in multiple languages. They were enthusiastic collectors of European poetry that encompassed the latest expressions of love. Beyond their familiarity with Dutch music, their exposure extended to French and even English songbooks and part music. The youthful suitor might have sung a love song, potentially one authored by poets such as Pieter Hooft. Hooft's verses, inspired by the traditions of Petrarch and De Ronsard, often found musical accompaniment, some of which were featured in his renowned work Emblemata Amatoria (Emblems of Love).

In spite of the presence of Dutch songbooks, foreign publications enjoyed greater popularity. Unlike other cultural forms, many people were well-acquainted with the melodies and lyrics of songs that resonated with the concerns of everyday individuals. These songs vividly portrayed the lifestyle of the jeunesse dorée (gilded youth) of the period. Crafted for convenient transport to festive gatherings, their scarcity today can be attributed to their deliberate use and handling.

The suitor's cloak

From a technical standpoint, the subdued olive hue of the suitor's cloak serves to discreetly contrast with the vivid red satin dress of the seated girl. This color choice prevents visual division between the two figures that might have occurred with a more colorful cloak. The sweeping and monumental folds of the cloak, a departure from Vermeer's usual style, not only enhance the gentleman's stature but also possibly underscore his masculinity. Cloaks were versatile garments that could be worn over a range of clothing. They were often used to cover and protect more formal or fashionable attire, particularly when outdoors. This practicality made cloaks a staple in the wardrobes of Dutch men.

From a technical standpoint, the subdued olive hue of the suitor's cloak serves to discreetly contrast with the vivid red satin dress of the seated girl. This color choice prevents visual division between the two figures that might have occurred with a more colorful cloak. The sweeping and monumental folds of the cloak, a departure from Vermeer's usual style, not only enhance the gentleman's stature but also possibly underscore his masculinity. Cloaks were versatile garments that could be worn over a range of clothing. They were often used to cover and protect more formal or fashionable attire, particularly when outdoors. This practicality made cloaks a staple in the wardrobes of Dutch men.

One of the many exquisite details of the composition is the gentleman's partially-revealed ruffled cuff that gently cradles the white wine jug. Positioned at a respectful distance, the gentleman stands poised to refill the young lady's glass—a gesture that implies she is nearing the end of her first glass. In 17th-century Dutch fashion, detachable cuffs made of lace or linen cuff (in Dutch (poinetten) were part of a broader European fashion trend during that time. They were designed to be seen protruding from beneath the sleeves of a coat or doublet, adding an element of refinement and fashion-conscious detail to men's attire. Ponietten could be highly ornamental, featuring intricate lacework and embroidery, which demonstrated the wearer's wealth and social status. However, they were also practical because they could be washed separately from the garments, helping to maintain hygiene and extend the life of the more expensive outer garments.

Critics have proffered diverse interpretations of this intimate tête-à-tête, often centered around the body language of the two figures. Walter Liedtke surmised that the girl's arms closed firmly around her body suggest a degree of discomfort, "as if the courtship were a troublesome necessity." Worth noting is the absence of the suitor's hands in the depiction, potentially indicating his reluctance to overtly reveal his amorous intentions. However, it's improbable that the young girl would have permitted the suitor to enter her private chamber and accepted a glass of wine if she did not feel assured of his honorable intentions—or at the very least, her capacity to maintain control over the situation.

The "Spanish" chair

In parallel with other works by Vermeer, the themes of gallant courtship and music making intertwine. A cittern rests upon a so-called Spanish chair, accompanied by a pillow beneath it. On the table lie a few opened songbooks. It is conceivable that mere moments earlier, the gentleman had been serenading the young lady with lively cittern music before altering his approach. Perhaps he believes that a few glasses of wine will better soften her heart.

The interplay of light across the intricately carved head of the cittern and the back of the chair constitutes one of the most evocative passages in the artist's body of work.

The type of Spanish chairs seen in the present work is characterized by their rigid yet lightweight construction, lionhead finials, leather upholstery and gilt lozenge patterns. These chairs represent a distinctive furniture style that emerged during the 17th century. They were often referred to as "lion's head" or "savonarola" chairs. Other types of Spanish chairs appear in Vermeer's works, each with different upholstery and finials. An example can be found in Vermeer's Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, featuring distinct blue chairs with their unique characteristics. Some lack the finials altogether.

The Chairmaker's Shop

Caspar Luyken

1694

Material and Technique

Engraving on paper, 142 x 81 c.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The construction of these Spanish chairs involved a framework made from wood, which provided both stability and a sense of regal grandeur. The lionhead finials, positioned prominently at the tops of the chair backs, lent an air of majestic strength and authority, while the leather upholstery not only added to the chairs' durability but also provided a touch of comfort and luxury. The gilt lozenge patterns, ornate geometric designs often applied to the leather, further accentuated the opulence of the chairs.

Vermeer's white-washed walls

Few painters, apart from Pieter de Hooch and Jacobus Vrel, have bestowed such meticulous attention on the unassuming white-washed wall. Vermeer's own depictions of walls seem to be the product of keen observation, meticulously recording the most subtle interplay of light and the textural nuances of their surfaces. The walls within The Milkmaid, The Music Lesson and The Art of Painting are so convincingly rendered that viewers often overlook their painted nature. Even skilled realist painters struggle to distinguish between paint and illusion on the nude wall within Woman with a Pearl Necklace, arguably the artist's most masterful interpretation of this modest motif.

However, in the present artwork, the subtle play of color and the deliberate detailing of the wall's surface cracks and stains are largely absent.

Given that a wall's color is inherently uniform in its whiteness, how can a painter imbue it with substance, texture and luminosity? What pigments, and in what proportions, are requisite to capture the wall's gradual shading as it recedes from the light source? Furthermore, how can the ethereal qualities of cast shadows be faithfully conveyed?

In this particular work, the primary constituents of the wall's paint encompass raw umber, a muted yet remarkably versatile brown; natural ultramarine; and, naturally, white lead, a stable but toxic white pigment, eventually supplanted by titanium white in the 20th century. It's worth noting that a similar blend, albeit in varying ratios, also graces the Girl with a Wine Glass. The wall has a subtle blue tinge that is not often noticable in reporductions, but that imaprs and airiness to the otherwise dimmly lit n motif,

The Turkish carpet

The Annunciation (detail)

Pedro Berruguete

late 15th century

Oil on panel

Monastery of Burgos Maria de Mileflores, Burgos, Spain

As observed in other Vermeer paintings, the figures convene around a table adorned with a "Turkish" carpet, a common feature of the era. Oriental carpets, introduced to painting during the fourteenth century, were strategically utilized by artists to direct focus toward important individuals or highlight significant activities. Renaissance artworks often positioned Christian saints and religious scenes on sumptuous carpets, leveraging them to enhance the perception of perspective. Subsequently, these carpets found their place in secular contexts, consistently symbolizing opulence, luxury, wealth and social standing. Though initially accessible solely to the most affluent, Oriental carpets became coveted by merchants and burghers, who frequently incorporated them in their portraits as tokens of acquired prosperity. By the seventeenth century, carpet depictions proliferated across Europe, captivating the Dutch in particular, who relished showcasing their technical prowess. While more Renaissance depictions of Oriental carpets have survived than actual pre-seventeenth century carpets, the late 19th century saw increased efforts by scientists and collectors to unearth surviving Oriental carpets, facilitating detailed comparisons with their painted counterparts.

Contrary to meticulously filling a precisely outlined sketch, the intricate decorative pattern of the carpet in The Glass of Wine is loosely defined by intermingling daubs of varied colored paint. The table's upper surface, viewed from a notably oblique angle, presents distinct technical challenges. Despite the absence of a recognizable underlying pattern, the rapid application of dashes and dabs of colored paint coalesce to evoke the carpet's soft texture and the rhythmic arabesque of its vibrant design, surpassing the effect of a perfectly rendered meticulous detail.

Beneath the carpet, sections of the robust, bulbous legs of an extendable table emerge—a table that reappears seven times in Vermeer's oeuvre. It was a practical piece of furniture that could be readily expanded by pulling out its leaves to accommodate more guests or activities.

The Rijksmuseum and other Dutch museums house similar tables, whose l bun-shaped feet later inspired the Dutch term for this furniture style—balpoot. The frame beneath the tabletop showcases decorative volutes, and beneath this, the legs are united by a double Y-frame stretcher. The table's core material is oak, adorned with a delicate rosewood veneer. Selected portions feature intricate ebony detailing. The table's dimensions measure 78.5 x 125 x 84 cm.

During the 17th century, tables held great value due to their expense. Many households contented themselves with a few planks supported by two barrels.

The wooden bench

The present work is one Vermeer's most extraordinary masterpieces, which in its sheer beauty, technical refinement, and extraordinary details may seem to defy analysis, and yet few of Vermeer's works are so carefully calculated.

Among the minor imperfections of this picture is the wooden bench set against the side wall, which appears seomwhat overly foreshortened. However, the treatment of the fall of light is uncanny and well worth the minimal disturbance. On the back lies a blue velvet braided cushion, which appears to be the same kind as the one that sits on the foreground chair.

Velvet, a luxurious and soft fabric, has been produced for centuries. In the 17th century, velvet was primarily made using silk, making it a fabric reserved for the wealthy. The process involved weaving two layers of fabric simultaneously on a special loom. The two layers were then cut apart, producing the pile effect seen on velvet. The height of the pile determined the plushness of the velvet. After weaving, the fabric was dyed using various methods, often resulting in deep, rich colors. The production was labor-intensive, and skilled craftsmen were essential for producing high-quality velvet.

The signature

Inscribed lower right window pane: IVMeer (VM in ligature)

(Click here to access a complete study of Vermeer's signatures.)

Dates

c. 1662 Albert Blankert, Vermeer: 1632–1675, 1975

c. 1659–1660

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., The Public and the Private in the Age of Vermeer, London, 2000

c. 1659–1660

Walter Liedtke, Vermeer: The Complete Paintings, New York, 2008

c. 1661–1662

Wayne Franits, Vermeer, 2015

(Click here to access a complete study of the dates of Vermeer's paintings).

Critical assessment

The fine, plain-weave linen with a thread count of 14 x 15 per cm² retains its original tacking edges; on both left and right sides are selvedges; The support has been glue/paste lined. The double ground consists of a white layer, containing chalk, lead white and umber, followed by a reddish brown layer. The ground was left uncovered along several outlines of the figures and the wine jug. It extends a few millimeters over the tacking edges.

Parts of the window, red dress, chair and many of the highlights were painted wet-in-wet, with impasto in the highlights, the fruit and the red skirt of the figure in the window. Ultramarine is used extensively in the window, the background, the tablecloth and in the underpaint of the shadows of the girl's red dress. The position of the heads of the standing man and the girl and the bows in her hair, have been slightly altered. Some parts of the painting appear unfinished, such as the wall between the male figures, and the arm and cuff of the girl. There is degraded medium in the ultramarine mixtures and the pigment appears discolored.

* Johannes Vermeer (exh. cat., National Gallery of Art and Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis - Washington and The Hague, 1995, edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr.)

Provenance

- Jan van Loon sale, Delft, 18 July, 1736, no. 16;

- John Hope, Amsterdam (1774-d. 1784); Hope heirs (until 1794);

- Henry Thomas Hope, Deepdene, Surrey (d. 1862);

- his daughter, Henrietta Adela (d. 1884);

- her son, Henry Francis Pelham-Clinton-Hope, London (until 1898);

- [Colnaghi and Asher Wertheimer, London];

- purchased in 1901 by the Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin (inv. 912c).

Exhibitions

- Berlin April–May, 1929

Die Meister des holländischen Interieurs

Galerie Dr. Schaffer

"Nachtrag" no. 103a and ill. - Schaffhausen 1949

Rembrandt und seine Zeit. Museum zu Allerheiligen

76, no. 188 and ill. - Brunswick September 6–November 5, 1978

Die Sprache der Bilder: Realität Und Bedeutung in der niederländischen Malerei des 17. Jarhunderts

Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum

164–168, no. 39 and ill. - Tokyo April 24, 1984–June 10, 1984

Dutch Painting of Golden Age from the Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis

National Museum of Western Art - Madrid February 19–May 18, 2003

Vermeer y el interior holandés

Museo Nacional del Prado

168–169 no. 33 and ill. - Tokyo August 2–December 14, 2008

Vermeer and the Delft Style

Metropolitan Art Museum

176–178, no 28 and ill. - Brunswick December, 2009–May, 2015

Epochal

Dankwarderode Castle - Kassel November 18, 2011–February 26, 2012

Light Structure - The Light in the Age of Rembrandt and Vermeer

Museum Hessen - Rome September 27, 2012–January 20, 2013

Vermeer. Il secolo d'oro dell'arte olandese

Scuderie del Quirinale

210. no. 47 and ill. - Tokyo October 5, 2018 –February 3, 2019

Making the Difference : Vermeer and Dutch Art

Ueno Royal Museum - Dresden June, 4–September 12, 2021

Vermeer: On Reflection

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

(Click here to access a complete, sortable list of the exhibitions of Vermeer's paintings).

Picture-within-pictures

The Quack (detail)

Anonymous Dutch painter

c. 1619–1625

Oil on panel, 67 x 90.7cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Vermeer's compositions are full of so-called pictures-within-pictures and in a sense, art becomes its own subject. However, the abundance of pictures-within-pictures in Vermeer's works is not only a personal choice, it reflects a real-life situation: paintings were more abundant in the Netherlands than in any other place in the world.

Foreigners who visited the Netherlands in the 17th century were amazed by how many pictures they found. In an oft-quoted diary, British traveler Peter Mundy wrote in 1640: "As for the art of Painting and the affection of the people to Pictures, I think none other go beyond them." In fact, paintings were everywhere except in the Reformed churches. In addition to well-off merchants, Mundy reported that bakers, cobblers, butchers and even blacksmiths all possessed at least one painting.

Since painting was no longer primarily the preserve of church or aristocracy or even the very wealthy, the types of pictures produced and sold as well as their appearance was drastically altered. The newly empowered urban upper class had discovered that paintings, as well as luxury items, could become an effective symbol of power, objects to be avidly collected and proudly exhibited. Consequently, paintings could also become another form of easily transportable merchandise in Holland which had become the Mecca of world trade. The fact that they were easy to handle and were less bulky made it easier to place them on the market.

Courtship in Dutch painting

The Suitor's Visit (detail)

Gerrit ter Borch

c. 1658

Oil on canvas, 71 x 73 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington

The present work is a perfect example of a new type of Dutch painting which explored the changing social mores of the second half of the 17th century pioneered by Gerrit ter Borch and Frans van Mieris.

Just a few decades before, a gentleman would not have been seen in the company of a young woman in a domestic setting. Prevailing customs did not allow private meetings between the wooer and wooed. During Vermeer's lifetime, when peace had been ensured and the Netherlands had become the most prosperous nation in Europe, the rules of courtship began to relax. Romance became a factor to be reckoned with and the private home became an accepted venue for negotiating marriage. However, the conventions of well-to-do courtship became restrained and increasingly ritualized. Artists, who had formally specialized in mercenary love of the brothels, discovered a brand-new market for scenes of barely veiled flirtations amidst the finely appointed bourgeois home.

Pieter de Hooch & Vermeer

Young Woman Drinking

Pieter de Hooch

1658

Oil on canvas, 69 x 60 cm.

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Even if Vermeer's thematic intentions remain uncertain, it is clear he had a demanding intellectual program for his more complicated works. The theme of this picture, courtship and love, had already been pioneered by Dutch artists decades before. Vermeer's foray into the new field was probably inspired by Pieter de Hooch.

Although De Hooch is probably the direct source of inspiration for this particular composition, Vermeer's art distinguishes itself from De Hooch's because it addresses more complex compositional and thematic issues. Whereas Vermeer's figures are brought prominently into the foreground and appear naturalistic, often with considerable sensitivity to their psychological states, De Hooch's figures are stiff, even doll-like, and sometimes do not appear anchored within the painting's three-dimensional space. Their postures are less natural and their emotions are seldom as nuanced as those of Vermeer. Also, while Vermeer dealt with moral questions of a certain weight (e.g., Last Judgment, Vanitas and religious faith) De Hooch favored less lighter subjects, focusing on home and hearth contents. However, to De Hooch's credit the historian Simon Schama holds that the artist's interiors portray tender child-rearing, "the first sustained image of parental love that European art has shown us."

Art historian Peter Sutton adds the interesting proposition that the woman and child who appear in so many of De Hooch's works are likely the artist's own wife and son, and the familiar rooms probably those of his own house. None of Vermeer's sitters have been identified.

The cavalier's felt hat

Portrait of Isaak Abrahamsz Massa

Frans Hal

1626

Oil on canvas, 79.7 cm × 65.0 cm.

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Although this kind of wide-brimmed hat could be made of wool or other materials, felt made from beaver hair produced a hat that held its form and was more weather resistant. A hat like the one in the present painting was not owned by everyone.

As the historian Timothy Brook noted, during the 17th century, beaver pelts imported from the New World were at the center of a lucrative web of trade since the beaver population of Europe had been largely depleted. The beaver-rich New World territory—eventually named New Netherlands—came under the jurisdiction of the Dutch West India Company in 1621, as part of the conditions of the Company's charter. The pelts were first sent to Russia, where they were valued for their shiny outside fur. Russian customers would eventually sell the furs back into the trade. When worn, dirty and sufficiently greasy to be properly felted they were converted into felt hats, and resold. Hatters used mercury to mat beaver fur's dense, warm undercoat. Exposure to the toxic chemical, however, caused severe mental disorders and is the source of the otherwise strange expression, "mad as a hatter."

Dutch wine

Parental Admonition (detail)

Gerrit ter Borch

c. 1654

Oil on canvas, 71 x 73 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

While grapes had been grown in the Netherlands since Roman times, the lack of sunlight meant that they produced poor wine. Nonetheless, fine wines could be easily imported from France, Germany, Spain and Portugal. This trade made the fortunes of many. Although wine was initially affordable for only the upper classes, by the 1650s wine consumption had outstripped that of beer. Young white wines from France and Germany were mixed with honey and spices to counteract their natural tartness and a fine end to a large meal.

Recommended for children and adults alike, beer was still the most popular beverage among the lower classes. Since it was boiled during preparation, it was safer to drink than plain water. In the countryside, buttermilk and whey were acceptable alternatives to beer, especially at breakfast, but whole milk was largely distrusted.

Another alcoholic drink, jenever, was also widely available in the Netherlands. Due to the lack of refined distilling techniques herbs were added to mask the flavor. The result was a juniper-flavored and strongly alcoholic liquor that was initially sold as medicine. By the late 1680s, the Dutch were exporting over 10 million gallons a year. Traditional jenever is still very popular in the Netherlands and Belgium.

Music in 17th-century Netherlands

Interior with a Musical Company

Joost Corneliszoon Droogsloot

1645

Oil on canvas, 97.7 x 126.8 cm.

Centraal Museum, Utrecht

Music played a significant role in the daily life of the Netherlands despite restrictions imposed by the Calvinist church. Wealthy burghers loved to flaunt their newly gained lifestyle in elegant musical gatherings where the display of expensive musical instruments played an important part.

As noted by the music critic and historian Julie Anne Sadie, a key vehicle for the diffusion of music in the Netherlands was the so-called collegia musica, which flourished in many important cities. Surviving documents provide insights into both social and musical attitudes and reveal that their importance extends far beyond the dilettantism usually associated with such groups. Town councils sometimes support a collegia by making a room available for the musicians. As early as the 17th century and increasingly in the 18th, collegia musica, supported by a wealthy bourgeoisie, gave traveling foreign musicians the opportunity to make public appearances, thus anticipating organized public concerts. In the 17th century, their repertory consisted largely of polyphonic songs and madrigals and simple instrumental music, some of which were of local origin. Authentic information about historical collegia musica is often fragmentary and has been preserved only by chance.

An invisible bond

Before settling on the upright format, Vermeer executed two interiors that are wider than they are higher. The horizontal format had been favored by the pioneers in the Dutch genre interior such as Willem Buyteweck and Dirk Hals but was later abandoned by, perhaps, the most refined practitioner of the motif, Gerrit ter Borch.

Vermeer must have recognized that in the horizontal composition, the painter is naturally constrained to dispose of both the objects and figures in a frieze-like sequence from left to right and that the observer tends to view them separately one after another as they read words in a book. This kind of reading did not worry the early painters since personal dialogue or figural unity was the last of their concerns.

Vermeer, instead, was more attuned to the private dialogue between the figures and attempted to bond the figures visually and emotionally. He did not have to look far for the appropriate compositional solution since it was one that he had already successfully employed in two earlier pictures, the Diana and her Companions and the Christ in the House of Martha and Mary. In all three paintings, the principal motif is unified with a circular composition, a common compositional device developed during the Renaissance.

In the present work the circular composition effectively balances the perspectival pull towards the background wall and the dazzling pattern of the stained-glass window.

Listen to period music

![]() The Lady Nevils Delight (cittern) [688 KB]

The Lady Nevils Delight (cittern) [688 KB]

from: Ancient Instruments - by Various Artists -Tuxedo (no. 33)

What do Vermeer's paintings mean?

Do Vermeer's paintings really signify something other than the scenes they represent?

After many years of research, scholars have concluded that there exists no single interpretative key to unlock the presumed hidden meanings of Vermeer's painting. Moreover, there is a growing sense that the iconographical method may have reached its limits. Some historians have gone full circle and return to what Thoré-Bürger expounded 150 years ago: Dutch paintings might be taken literally for what they appear to be at first glance, remarkable descriptions of a particular situation and time.

The principal advocate of the iconographic method as applied to Dutch genre paintings is Eddy de Jongh. Rather than assuming naturalism as the default mode of representation, in De Jongh's system, everyday objects are interpreted as having symbolic meanings that, taken together, contribute to the meaning of the painting as a whole. While in the Vanitas imagery of Dutch still lifes symbolic meaning of certain objects and events was intentionally blunt—hourglasses, timepieces or spent candles signaled the ephemerally and futility of the material world—genre scenes of the kind painted by Vermeer demanded an all-encompassing approach. Their symbolic messages are embedded deeper within the apparently quotidian. Unlike Panofsky, the originator of iconographical studies of Renaissance painting, De Jongh spoke of "apparent realism," rather than "disguised symbolism" since the illusionist appearance in Dutch paintings is nonetheless its most remarkable trait. To support his readings, De Jongh marshaled an array of texts and prints which in turn help to produce a picture of the broader cultural context for viewing these works.

Many believe that beneath the extraordinary realism of Dutch art lies an allegorical view of nature that provided a means for conveying various messages to contemporary viewers. The Dutch, so it goes, with their ingrained Calvinist beliefs, were a moralizing people. While they thoroughly enjoyed the sensual pleasures of life, they were keenly aware of the consequences of wrong behavior. Paintings, even those representing everyday objects and events, helped provide reminders about the brevity of life and the need for moderation and temperance in one's conduct.

The iconographical approach to Dutch paintings has found detractors. Many believe that the average Dutchman had no need to be told what was morally right or wrong. In her groundbreaking study, The Art of Describing, Svetlana Alpers forcefully advanced the opposed notion of Dutch painting, unlike Italian painting, as essentially descriptive and non-narrative, supported by a fascinating array of ideas and data culled from different fields, including optics, perspective theory and cartography. In her view, Dutch painters participated in a distinctive visual culture that led them to value detailed realistic paintings of everyday life as a way of exploring and knowing the world, not as a way of presenting disguised moralistic meanings.

The latest development in the iconographical vein is that paintings were deliberately meant to have open-ended meaning, a sort of interpretative ambiguity where the final significance of the painting depends upon the emotions and cultural experiences of the viewer. Indeed, ambiguity is already latent in many important symbols. Mirrors, for example, were associated with both vanity and self-introspection.

Some scholars believe, in essence, that both are right. Dutch painters deliberately created open-ended works which viewers could interpret symbolically or delight in the astounding visual qualities represented therein.

Vermeer & the fijnschilders

Along with Gerrit Dou, Gerrit ter Borch and Frans van Mieris, Vermeer practiced what the Dutch called "fijnschilderei" or "fine painting." This new, ambitious form of painting catered to the quasi-aristocratic burgher tastes which had developed after the 1650s when religious inhibitions in regards to the accumulation and display of materials riches began to loosen. In this period, Dutch burghers, many of whom had retired from work and were able to live on their investments and land holdings, desired to distance themselves off from the rest of society. The construction of grand villas, luxurious city dwellings and formal gardens were among their favorite pastimes and art collecting became a means to not only boast their princely lifestyle but to define their social aspirations as well.

In order to gratify the burghers whose life-style had not yet been pictured, the fijnschilder painters focused on precious, expensive, cultivated things, above all clothes and interior furnishings. Favored motifs were conversation, gallant courtship, music making, poetry, letter reading and letter writing. The direct, emphatic display of emotion was banished in favor of self-containment and barely perceptible gesture. To convey the new social mentality, a consonant style and a technique were required. They favored polished, almost invisible brushwork and a detailed description of form necessary to capture the textures and colors of luxurious furnishings and costumes. The earlier drab earth colors, jumbled compositions and indistinct lighting practiced by painters of low-life tavern scenes and bare home settings gave way to clear, bright lighting, geometrically ordered compositions and rich colors. The surface of fijnschilder paintings remains virtually undisturbed by paint relief.

Gallant Conversation, Known as "The Paternal Admonition"

Gerrit ter Borch

c. 1654

Oil on canvas, 69 x 60 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Since this new type of painting required great skill and expenditure of time, prices rivaled those paid for the finest works of the venerated Italian masters. A good Dou could fetch over 1,000 guilders, the equivalent of the price of a modest Dutch house. Dou, Van Mieris and Ter Borch all had international reputations while the great part of Vermeer's oeuvre was acquired by the patrician Pieter van Ruijven of Delft who, in order to bolster his social standing, paid an astronomical sum of 16,000 guilders to acquire land near Schiedam, which brought with it the title of Lord of Spalant in 1669.

A new hypothesis on the origin of the painting

In a recent paper, Huib Zuidervaart has advanced an interesting theory on the origin of Vermeer's Glass of Wine and The Girl with a Wine Glass. Zuidervaart asserts that the two works, which represent an open window that features an identical coat of arms, were commissioned as wedding presents for two of the grandchildren of Moijses van Nederveen and Janetge de Vogel. Moijses van Nederveen came from a prominent Delft family which was one of the four local producers of gunpowder, delivered to the Dutch army. Although historians had previously identified the families to which the coat or arms belonged—the heraldic emblem is a combination of those belonging to the Van Nederveen and De Vogel families—no one had as of yet explained why Vermeer would have chosen to include such a conspicuous element into two ambitious compositions. Zuidervaart points out that dates given to both paintings by Vermeer experts coincide with the dates of the weddings in question. Moreover, the symbolic implications of the coat of arms (figure of female virtue holding a crest) would appear in agreement with the idea as a wedding gift as well as being consistent with the background of Vermeer's presumed clients. Given that both paintings present not only the same window but the same set of ceramic tiles, which Vermeer never painted again, it is also possible that the Delft master executed both works on the premises of the Van Nederveen/De Vogel residence in Delft.

special topics

- The 17th-century Dutch art market

- A new hypothesis on the origin of this painting

- The theme of courtship in Dutch painting

- Pieter de Hooch and Vermeer

- Hidden meanings?

- Vermeer and the fijnschilders

- The cavalier's felt hat

- Dutch wine

- Music in 17th-century Netherlands

- An invisible bond

- What do Vermeer's paintings mean?

- Listen to period music