The Milkmaid

(De Melkmeid)c. 1657–1661

Oil on canvas, 45.5 x 41 cm. ( 17 7/8 x 16 1/8 in.)

The Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

inv. A2344

The textual material contained in the Essential Vermeer Interactive Catalogue would fill a hefty-sized book, and is enhanced by more than 1,000 corollary images. In order to use the catalogue most advantageously:

1. Scroll your mouse over the painting to a point of particular interest. Relative information and images will slide into the box located to the right of the painting. To fix and scroll the slide-in information, single click on area of interest. To release the slide-in information, single-click the "dismiss" buttton and continue exploring.

2. To access Special Topics and Fact Sheet information and accessory images, single-click any list item. To release slide-in information, click on any list item and continue exploring.

A simple window

This rustic window, presumably the same one in the earlier Officer and Laughing Girl, differs in structure and rendering from the more intricate ones that populate Vermeer's later pictures. Slight interplays of light and texture, like a broken piece of one of the panes, are captured with exceptional precision and creative verve.

Leaded windows, constructed by joining small pieces of glass with lead cames, were a prominent feature in both modest and extravagant buildings in 17th-century Netherlands. They varied from the more straightforward designs in common households, like the one in The Milkmaid, to the intricately detailed construction such as those in Vermeer's The Glass of Wine. These windows were often divided into multiple panes, sometimes featuring colored glass and highly ornate patterns.

The Crown method

During the 17th century, the production of glass for windows—the "Crown" method— involved a meticulous and traditional process that followed a series of well-defined steps. First, artisans began by sourcing high-quality raw materials, including silica-rich sand, soda ash and lime.

The next step was to melt the glass batch in a furnace heated by wood or charcoal. The intense heat caused the mixture to melt and fuse into molten glass. Skilled glassblowers used a blowpipe to gather a portion of molten glass, shaping it into a hollow bubble through controlled blowing. This annealing process relieved internal stresses and prevented cracks from forming. Once cooled, the glass bubble was reheated and spun on a flat surface to create a flat, circular glass sheet.

This sheet was then cut into smaller rectangular pieces through scoring and gentle breaking along the scored lines. The edges of these glass panes were meticulously smoothed, less they chip, and refined using techniques like grinding and polishing, ensuring their safety and usability.

Assembling the windows involved carefully fitting the smaller glass panes into larger ones using lead cames—lead strips with varying profiles. The lead cames were shaped to encase the edges of each glass pane, forming an intricate lattice that held the panes together. These joints were then soldered to secure the glass panes and provide structural stability. The production method of making glass naturally resulted in waves, bubbles and other irregularities. When light passed through these imperfections, it would refract in unpredictable ways, giving the glass a wavy or distorted look, which we can clearly see in Vermeer's Officer and Laughing Girl.

To weatherproof the windows and enhance stability, craftsmen applied glazing putty around the edges of the leaded glass. This putty was a mixture of linseed oil, chalk and pigment.

Compositional dynamics

Critics have always noted that almost every compositional element in Vermeer's works is determined with the utmost care to direct the spectator's eye to the points of thematic interest and create an indivisible expressive unit. The cascade of the black frame, the basket and the brass marketing pale all lead the eye down towards the thematic center of the painting: "the pouring milk." At the same time, each of these three objects preserves its distinct form and texture, which are immediately distinguishable. The critic Edward Snow wrote that The Milkmaid "is a melody of contrasting textures. The pair of hanging baskets provide the key: rough and smooth, hard and soft, woven and molded, curved and angular, open and shut." Consider especially the shifting interplay of organic and manufactured forms (the bread and milk against the containers and the table; the wicker basket against the metal one..."). In any case, even though there are many different objects in the painting, a sense of benign order reigns throughout.

The wicker bread basket, presumably, held bread, the lifeline of any Dutch family, was hung high on the wall away from mice. Wicker baskets, crafted from pliable materials such as willow and reed, were a staple of 17th century Dutch households. The wicker's flexibility allowed for intricate weaving patterns that ensured durability and provided ventilation, keeping bread fresh.

Curiously, when Vermeer died he owed the considerable sum of 617 guilders to the baker and occasional painting client, Hendrick van Buyten. This debt was probably not unusual for the time. After the painter's untimely death, his widow, Catharina Bolnes, turned over two paintings as collateral, a rather generous gesture on the part of the baker. Similar pails appear in many Dutch interior paintings of the time although Vermeer's is smaller and more finely decorated than most.

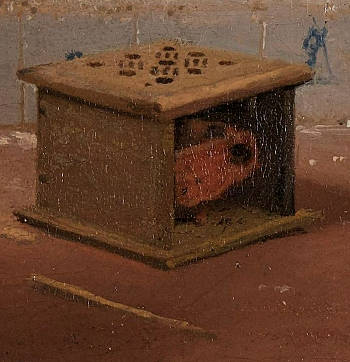

The Dutch footwarmer

In many Dutch homes, one would have stumbled across a foot warmer or foot stove ("stoof" or "stoofje" in Dutch), a little wooden box with a perforated top and sometimes perforated sides. Inside these curious objects was a receptacle of pottery or metal filled with hot coals that served to keep one's lower parts warm during the long, gelid Dutch winter, a necessity particularly in damp, poorly heated houses with stone or brick floors. They would have only been found in middle-class homes. While the one featured in Vermeer's Milkmaid is a simple affair, some footwarmers were decorated with elaborate carving, which commemorates family ties, religious beliefs, or national preoccupations. Sometimes they were carried on long carriage or barge trips, although the poor are said to have had to make do with hot potatoes. Curiously, the base was often as elaborately carved as the other sides because when they were not in use, foot warmers were hung from a ceiling beam to save space. They appear an infinite number of times in Dutch interior paintings. The types of footwarmers used by the Dutch were also common in northern Germany.

Although Vermeer may have depicted the foot warmer as an incidental slice of daily life, he may have intended to convey some symbolic meaning. In emblematic literature of the day, footwarmers were sometimes associated with a lover's desire for constancy and caring, an idea reinforced by the cupid images on the tiles directly behind it. As Walter Liedtke pointed out, it may allude to the maid's inner warmth or even have a sexual implication since the warmth of the coals moved upwards under the skirt towards the lady's private parts.

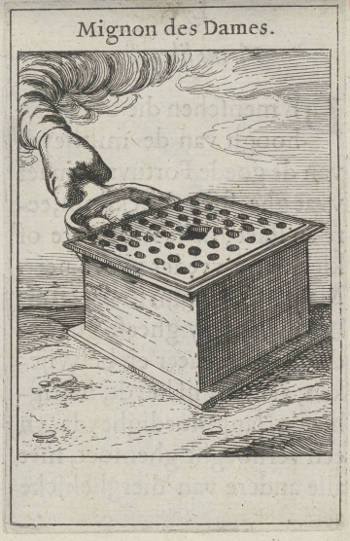

"Mignon des Dames" from Sinnepoppen

Roemer Visscher

1614

Engraving

Universiteits-Bibliotheek, Amsterdam

The foot warmer motif appears in the famous emblem book Sinnepoppen by Roemer Visscher, in which a stove with a firepan is referred to as "Mignon des Dames" or "Love of the Ladies." The text reads that in winter, women cherish their warm stoves above all else. And should a man come along, even if he tries his hardest, he can only hope to be second best.

Emblem books were a popular genre in the 16th and 17th centuries. They featured an illustration, an aphorism and an explanation (typically in rhyme) on each page. None of these elements could be fully understood without the other two. In 1612, several of Visscher's poems were printed in Leiden without his consent. In response, he commissioned the renowned Amsterdam publisher Willem Jansz Blaeu, particularly known for his atlases, to publish his own edition of Sinnepoppen.

During the initial two decades of the 17th century, Visscher's residence on Geldersekade in Amsterdam served as a hub for the city's cultural elite. The Dutch poet Vondel described the revered Roemer's home as a place "Whose floor is daily trod, whose threshold even worn bare by painters, artists, poets and singers from all around."

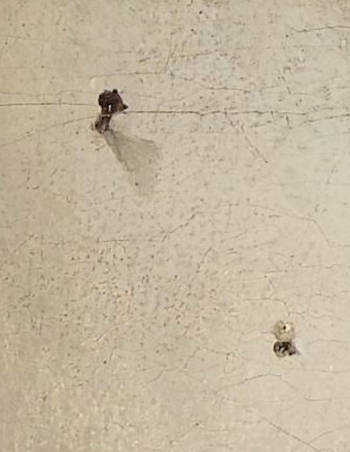

A humble nail

This nail—another large nail is above the hanging bread basket—presumably held a framed painting or decorative map. It casts a small shadow on the plaster to the right, signaling the light originates from the left. To the right of the figure's head appear a few nail holes.

Until around 1600, wrought handmade nails ("wrought" means beaten into shape by hammer blows rather than cast in its final shape by pouring liquid iron into a mold), nails one by one was one of the blacksmith's many jobs. To make nails the blacksmith first made a square iron rod, for the nails' so-called shank. Heated in a forge, the rod would be hammered on all four sides to form a point. The pointed nail rod was then reheated and cut off. Then, each nail was forced into a hole in a nail header or anvil and beaten with several glancing blows of the hammer to form the nail's head. One of the most common types of nail head was a convex hammer-rounded "rose," made with four or five hammer blows. Being made by hand, nails were relatively scarce and expensive. Nails were so valuable in the early American settlements that in 1646 the Virginia legislature had to pass a measure to prevent colonists from burning down their old houses to reclaim the nails when they moved. Nails provide one of the best clues to help determine the age of historic buildings.

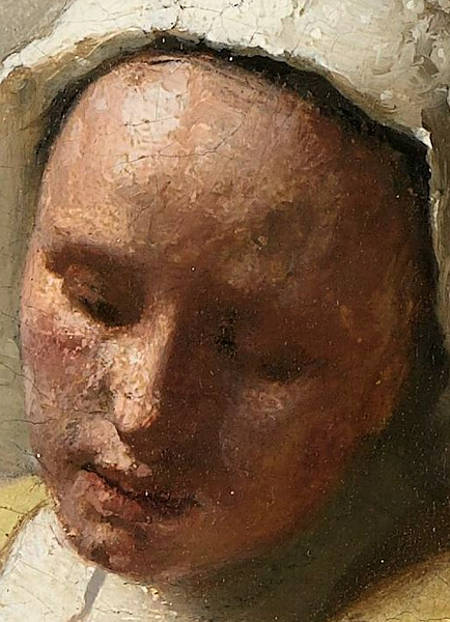

The model: Vermeer's wife Catharina?

The extraordinary tactility of this picture is particularly evident in the modeling of the woman's head and bodice. Small touches of paint—white, light ocher, reddish-brown, brown, greenish-gray—coalesce magically in the form of a solid head that seems to think and breathe. Brushstrokes, albeit tiny, are boldly juxtaposed with little or no blending. The buildup of paint is so pronounced that one has the impression that Vermeer was attempting to sculpt rather than paint the head.

Critics have frequently speculated that the model for this painting was Tanneke Everpoel, Vermeer's family maid. Through archival documents of 1663, we know something of her temperament. She had once defended Vermeer's wife Catharina from an attack by her lone and wild-tempered brother, Willem Bolnes, which had occurred some years earlier.

The events were recorded in a notary public deposition of several people, Willem de Coorde, Gerrit Cornelisz., stone carver and Tanneke herself, who testified concerning Willem's abusive character. Tanneke and Gerrit the stone carver testified: "That on various occasions Willem Bolnes had created a violent commotion in the house—to such an extent that many people gathered before the door—as he swore at his mother, calling her an old popish swine, a she—devil, and other such ugly swear words that, for the sake of decency, must be passed over. She, Tanneke, also saw that Bolnes had pulled a knife and tried to wound his mother with it. She declared further that Maria Thins had suffered so much violence from her son that she dared not go out of her room and was forced to have her food and drink brought there. Also, Bolnes committed similar violence from time to time against the daughter of Maria, the wife of Johannes Vermeer, threatening to beat her on diverse occasions with a stick, notwithstanding the fact that she was pregnant to the last degree."

Luckily, on this occasion, Tanneke was able to prevent some of this violence herself. Moreover, De Coorde declared that on several occasions, warned by Tanneke, Willem had blocked Bolnes from entering the house: "He also had seen Willem several times thrust at his sister with a stick at the end of which there was an iron pin."

Vermeer's mother-in-law, Maria Thins, eventually succeeded in having Willem committed to a house of correction. Many specialists have drawn attention to the fact that the crude domestic violence which plagued the Vermeer household never once found its way into the artist's peaceful compositions.

The maid's yellow bodice

The milkmaid is dressed in various layers of clothes. She wears a sturdy, leather yellow bodice top with rough, reddish stitching and a blue apron over a heavy red wool skirt, suggesting that the picture was painted in the winter. Maids and other domestic workers in Dutch paintings of the 17th century are often portrayed in relatively simple and utilitarian clothing, suitable for work. These were typically made of durable materials that could withstand daily chores. The colors were often muted, such as dark blues, browns, or blacks, as these would not show dirt and wear as readily. With this in mind, the milkmaid's yellow bodice would have easily been soiled so it may have been fruit of artistic licence rather than a faithful recording of a particular garment.

The bodice is modeled much with the same technique as the maid's down-turned face and the still life, composed of an interminable series of briskly applied dabs of thick yellow and brown paint, a technique which imitates the rough texture of the garment itself. The yellow pigment used to depict it has been identified as lead-tin yellow, the brightest yellow pigment available in Vermeer's time. The same pigment is to be employed in later representations of the famous fur-trimmed morning jackets adorned by elegant women.

After The Milkmaid, Vermeer never again turned his attention to a working-class theme.

The maid's "mess sleeves"

Woman with a Child in a Pantry (detail)

Pieter de Hooch

c. 1656–1660

Oil on canvas, 65 x 60.5 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

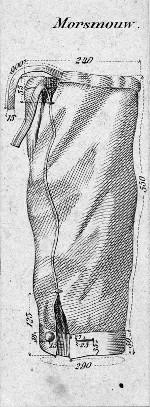

18th-century diagram of morsmouwen

These curious roughly stiched green work sleeves (chamois leather?) are called morsmouwen or "mess sleeves." Made of wool or heavy silk, they are not a part of the yellow bodice but are worn separately to protect against staining. They can be occasionally observed in the works of other painters, such as Pieter de Hooch's Woman with a Child in a Pantry (image above left).

In this detail, Vermeer displays his ability to create very different colored draperies from a limited palette. First, the sleeves were modeled in shades of monochrome brown, defining the meandering folds with chiaroscural values. The lightest areas were accentuated with a pale admixture of white and ultramarine blue. Once dry, the outer parts were glazed with a transparent yellow, creating a greenish tint. The turned-up, underparts remained unglazed.

The earthen pot and a bit of milk

Whatever symbolic or practical meaning Vermeer had wished to assign to the milk which falls into the stoneware receptacle below, it is the focal point of the painting as well as the maid's attention. It has been pointed out that the artist chose not to depict the milk inside the jug, which, instead, would have been visible given that the artist's viewpoint was above the lower lip of the jug. In linear perspective, the horizon line represents the viewer's eye level. Anything below this line should, in theory, show its top surface to the viewer if the object is tilted in the viewer's direction, and vice versa for objects above the line. Given the placement of the horizon line in The Milkmaid (which is determined by the height of the left-hand arm of the figure), the top surface of the milk inside the jug should be visible if the jug is tilted towards the viewer. Thus, the flow of the milk from the jug and its flat surface should be observable until the pouring action is entirely ceased.

The two-handled bowl and pitcher are examples of redware, which in this period was mostly produced in the town of Oosterhout in North Brabant. The pot served for prolonged cooking. Stoneware was made of clay that produces a gray or brown color when it is fired at a temperature of around 1250 degrees Celsius. It is exceptionally hard and only slightly porous. Moreover, stoneware does not acquire a taste and is easy to clean. It is an ideal material in which to preserve liquids and from which to drink. Around 1300, stoneware acquired something of a mass market and remained popular until glass and Delftware took its place in the 17th century.

In order to intensify the rich brick color of the stoneware vessels, the artist applied dabs of light blue here and there where one might expect to find reflections, a technique unusual for the time when objects were described strictly with their local colors and anonymously colored dark shadows.

Picturing light & Westerwald pottery

More ink has flowed to describe the poetic and optical qualities of this still life than perhaps for any other detail in Vermeer's oeuvre. The bread, basket, pitcher and bowl display such vibrancy and tactility that they effectively vie with the woman as the focus of the painting.

To achieve the extraordinary luminosity emanating from this work, Vermeer reconstructs, rather than represents, the activity of light with a complex layering of paint. Thick impasto paint is used to render the rough textures of the objects, while thin glazes nuance local color and deepen shadows. The famous pointillés, or spherical dabs of thick opaque paint clearly evident in this detail, suggest nothing more than light as it flickers off the fractured topography of the bread, stoneware and basket. Their presence implies that the artist used a camera obscura as an aid to the painting process.

The studded beer jug with a pewter lid was most likely manufactured in the Westerwald region of the Rhineland, situated in the southeastern part of the Netherlands.

Pottery production in the Westerwald region is known from the beginning of the 15th century, but an influx of migrant potters from Siegburg and Raeren helped establish the stoneware industry toward the end of the 16th century. The industry grew in the 17th century and remained strong well into the 18th and 19th centuries, with exports not only to Britain but also to Australasia, Africa and America. Westerwald stoneware displays colors ranging from light to mid-gray, with their surfaces usually treated with a salt glaze, resulting in the characteristic "orange peel" effect. Additionally, cobalt blue and manganese purple painted details are added. These two colors were the only ones capable of withstanding the high-firing temperatures of the stoneware kilns.

A workday apron painted with precious natural ultramarine

The dark blue apron and the similarly colored cloth that drapes from the table possess a stunning inner luster that cannot be adequately captured in reproduction. To achieve this effect, Vermeer applied one or two thick transparent layer(s) of the costly natural ultramarine (made of crushed lapis lazuli imported from Afghanistan) over a vigorously defined monochrome underpainting, most likely executed in strongly contrasting shades of black and white, a standard practice since oil painting was invented.

The transparent layer of paint, called a glaze, produces an effect analogous to that of stained glass. For painting blue objects, contemporary painters, instead, usually employed the cheaper blue called azurite, which, however, does not possess the depth or the prized purplish undertone of true ultramarine. Some scholars have speculated that it was Vermeer's rich Delft patron Pieter van Ruijven who supplied the artist with such costly pigment, seeing that only a few years before The Milkmaid was painted, the young Vermeer did not have enough money to pay in full the entrance fee to the Saint Luke Guild, the trade organization of Delft's artists and artisans.

The costume historian Marieke de Winkel explained that the aprons were worn by maids—unlike the white aprons worn by ladies of the house—were often dark blue to mask stains. As in Vermeer's Milkmaid, many Dutch paintings portray maids wearing deep blue aprons. The blue hue was achieved using indigo, a dye sourced from the indigo plant. Indigo was one of the few dyes in pre-industrial times that could produce a strong and fast blue color. The blue hue in the aprons was often achieved using indigo, a dye sourced from the indigo plant (Indigofera tinctoria). Indigo was one of the few dyes in pre-industrial times that could produce a strong and fast blue color. Although indigo is generally a somewhat dull blue—think of blue jeans—, the highest quality, used, for example, in tapestry production, can be particularly brilliant.Blue aprons are seen on the servants in Vermeer's Mistress and Maid and in A Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid.

The green tablecloth

Although it cannot be fully appreciated in many reproductions, the green tablecloth, which softly glows in the original, mediates between the lustrous blue of the maid's wrap and the yellow warmth of the basket and bread.

Despite their apparent realism, we can never be sure that the colors of the objects we see in Vermeer's paintings were those that the painter observed before him. Altering the color of simple objects, especially drapery, is a simple task for the trained artist, who had at his fingertips an array of recipes, some of which made their way into art manuals of the period, for coloring objects realistically.

Occasionally, these texts would provide specific guidance for depicting particular objects, surfaces, or effects. For example, how to render the sheen on a pearl, the texture of a particular fabric, a the hide of a white mare or the play of light on different metal or glass surfaces. However, even with these guides, artists were advised to observe nature directly to best render it in their works. It's worth noting that while many recipes and techniques were shared in such manuals, others were closely guarded secrets passed down within workshops or between masters and their apprentices. Sometimes, these recipes could be quite specific, like how to color the body of a white mare.

Delft hand-painted tiles

The decorated white tiles, seen in more than one work by Vermeer, were made in Delft and were used for covering the lower areas of inside walls and the inside of the hearth. They hid the damp spots on the ground-floor walls and provided a skirting that protected the plaster from the daily assault of brooms and mops. Such tiles were little works of art in their own right and often displayed games of children, Cupids and other amusing themes which Vermeer utilized to tell part of the story of his paintings. The refined and world-renowned Delftware was produced only in the later years of Vermeer's life. Delft porcelain, which initially imitated Chinese imports for local use, became so desirable that it was soon exported not only to Flanders, France England and Spain, but to the West Indies as well.

One of the tiles which Vermeer added displays a fairly recognizable Cupid with a cocked bow trapped midway between the milkmaid's voluminous skirt and the footwarmer. Two leading scholars, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Walter Liedtke, have favored specific interpretations of this minuscule detail. According to Liedtke, the Delft tile to the left of the foot warmer suggests that Vermeer's milkmaid was meant to be seen not in any narrative context but as a "discreet object of desire."

The same description would serve for most of the women in Vermeer's early work and would suit the great majority of milkmaids and kitchen maids in Dutch art, except that there is usually nothing discreet about them. And yet Wheelock has celebrated the milkmaid as a madonna of the cow-meadows who embodies everything pure and wholesome, indeed "an ideal of human dignity" with a "physical or moral presence unequalled by any other figure in Dutch art."

However, since no period text documents that genre painters availed themselves of such symbolic refineries, some scholars remain skeptical. For example, Taco Dibbits observed that similar Cupids were found on tiles all over Dutch houses, and that the Cupids presence may be merely coincidental and that in the present context need not mean anything very much at all.

The Dutch maid

From the point of view of the 21st-century observer, it is hard to imagine a more wholesome image than Vermeer's Milkmaid. In Vermeer's time, instead, the handsome young milkmaid may, as Walter Liedtke has written, have been seen as "a discreet object of desire." Liedtke relates that 17th-century Dutch viewers, like Vermeer's patron Pieter van Ruijven, were "well acquainted with the reputation of kitchen maids and especially milkmaid, who were known for their sexual availability." Liedtke cites examples of Netherlandish prints which propagate this common opinion.

Although the theme of the "available" milkmaid was largely domesticated in the works of the Leiden painters of the fijnschilder school, Vermeer nonetheless knew he could count on its familiarity when he contrasted the rough leather sleeves with the fleshy nudity of her exposed forearm, which as Liedtke puts it, "is frankly alluring in its own way."

In any case, the figure pouring milk in Vermeer's painting is not actually a milkmaid, but more properly, a kitchen maid. Milkmaids milk cows, kitchenmaids work in kitchens.

The maid's mess sleeves

Woman with a Child in a Pantry (detail)

Pieter de Hooch

c. 1656–1660

Oil on canvas, 65 x 60.5 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

18th-century diagram of morsmouwen

These curious green and blue work sleeves are called morsmouwen or "mess sleeves." Made of wool or heavy silk, they are not a part of the yellow bodice but are worn separately to protect against staining. They can be occasionally observed in the works of other painters, such as Pieter de Hooch's Woman with a Child in a Pantry (image above left).

In this detail, Vermeer displays his ability to create very different colored draperies from a limited palette. First, the sleeves were modeled in shades of monochrome brown, defining the meandering folds with chiaroscural values. The lightest areas were accentuated with a pale admixture of white and ultramarine blue. Once dry, the outer parts were glazed with a transparent yellow, creating a greenish tint. The turned-up, underparts remained unglazed.

The red petticoat

A petticoat is essentially an underskirt, often worn to give volume to the skirts worn over them. By the 17th century, the petticoat could also be an outer garment, worn visible underneath an open-fronted gown or dress. Women might wear several petticoats.

Red petticoats are commonly pictured in Dutch interior paintings. The popularity of this garment is testified by the fact that they were worn by both ladies of the household and maids. Materials ranged from luxurious silks for the wealthy to simpler wool or linen for the common folk. The kind of material and the quality of the petticoat would give hints about the socio-economic status of the depicted person.

Various red dyes were available in the 17th century. Among these were madder, one of the oldest known red dyes, which is derived from the root of the Rubia plant. Cochineal is another dye, coming from the cochineal insect primarily found in South and Central America. Kermes, derived from a Mediterranean insect, and Brazilwood, a red dye sourced from the heartwood of trees such as Brazilwood, were also commonly used. Madder was most likely the dye used to give color to the red petticoat of the milkmaid. While not as brilliant as some insect-derived reds, madder was widely used for centuries due to its relative affordability and accessibility.

Since 17th-century painters lacked a deep red of the kind shown in the paintings, red objects were first modeled in shades of vermilion, a popular orange-toned pigment, and black for the deepest shadows. When dry, the whole passage was glazed with a thin layer of a highly transparent pigment called red madder. The layer of madder not only deepened the vermilion without hiding the tonal contrasts but protected it from turning black. Given its vibrant depth, Vermeer must have layered this passage with more than one glaze of madder.

Vermilion (mercuric sulfide), also known as cinnabar, was found in mineral extraction localities that yielded mercury, notably at Almadén (Spain). This mine was in operation from Roman times until 1991 and remained for centuries the preeminent cinnabar deposit worldwide. Vermilion's well-known propensity to turn black over time is evident in works from ancient Roman frescoes to Baroque paintings by Peter Paul Rubens. Although the cause of this defect was previously unknown, researchers have determined that elemental mercury is responsible. The chemist Katrien Keune demonstrated that the compound can degrade through a series of chemical reactions initiated by chlorine ions—particularly abundant in coastal air—in conjunction with light.

Painting white-washed walls

Although rarely discussed, the prosaic white-washed wall which set the stage for the artist's quiet little dramas are crucial components of Vermeer's interiors. These walls not only mark the furthest limits of pictures' implied three-dimensional space but silently orchestrate the mood of each scene and establish the broader scheme of illumination by which the chiaroscural and chromatic relationships of the architectural features, figures and movable objects can be appropriately gauged.

A Merry Company (detail)

Anthonie Palamedes

1633

Oil on panel, 61 x 89 cm

.

Hallwyl Museum, Stockholm

Interior with a Merry Company

Joost Cornelisz. Droochsloot

1645 Oil on canvas, 98.5 x 127.9 cm.

Centraal Museum, Utrecht

In oil painting, the naturalistic rendering of a brightly lit wall, such as those found in the Delft works of Pieter de Hooch, Antonie Palamedesz. or Vermeer, is a challenging undertaking. However, while Vermeer's colleagues depicted walls in a fairly summary and standardized manner, attentive examination shows that Vermeer experimented with a more refined and broader range of techniques just as he had done with others of his preferred motifs (e.g. leaded windows, floor tiles, wall maps etc.). Vermeer's exceptional powers of observation and pictorial synthesis allowed him to capture nuances of light, shade and texture in his walls that his colleagues either ignored or were unable to represent.

In Vermeer's walls, the broader left-to-right chiaroscural variation immediately establishes the direction and intensity of the incoming light and how it gradually diminishes as it flows obliquely over its surface. Nail holes, cracks, crevices and other minor surface irregularities are recorded with discreet variations in the paint's tonal values. In some works, such details are "literally" depicted with darker and lighter paint; in others, by digging the stiff-bristled brush into the wet, light-toned paint, exposing here and there the underlying darker ground. Sometimes paint is used metaphorically. By piling up thick paint impasto in the lighter areas of the wall, the painter evoked not only the strength of the light that illuminates its surface but also their crusty texture produced by repeated coatings of lime that were necessary to maintain the walls clean, fully reflective and hygienic. Minor cast shadows, instead, were often painted with thin, semi-transparent layers of darker paint to suggest their insubstantial nature. The contours, tones and shapes of the shadows cast by the windows, paintings-within-paintings, maps, etc. provide more precise information about the intensity and direction of the light as well as information about the morphological characteristics of the objects which cast them.

Painting White-Washed Walls

Although rarely discussed, the prosaic white-washed walls that set the stage for the artist's quiet little dramas are crucial components of Vermeer's interiors. These walls not only mark the furthest limits of picture's implied three-dimensional space but silently orchestrate the mood of each scene and establish the broader scheme of illumination by which the chiaroscural and chromatic relationships of the architectural features, figures and movable objects can be appropriately gauged.

A Merry Company (detail)

Anthonie Palamedesz.

1633

Oil on panel, 61 x 89 cm

.

Hallwyl Museum, Stockholm

In oil painting, the naturalistic rendering of a brightly lit wall, such as those found in the Delft works of Pieter de Hooch, Anthonie Palamedesz. or Vermeer, is a challenging undertaking. However, while Vermeer's colleagues depicted walls in a fairly summary and standardized manner, attentive examination shows that Vermeer experimented with a more refined and broader range of techniques just as he had done with others of his preferred motifs (e.g. leaded windows, floor tiles, wall maps etc.). Vermeer's exceptional powers of observation and pictorial synthesis allowed him to capture nuances of light, shade and texture in his walls that his colleagues either ignored or was unable to represent.

In Vermeer's walls, the broader left-to-right chiaroscural variation immediately establishes the direction and intensity of the incoming light and how it gradually diminishes as it flows obliquely over its surface. Nail holes, cracks, crevices and other minor surface irregularities are recorded with discreet variations in the paint's tonal values. In some works, such details are "literally" depicted with darker and lighter paint, in others by digging the stiff-bristled brush into the wet, light-toned paint exposing here and there the underlying darker ground. Sometimes paint is used metaphorically. By piling up thick paint impasto in the lighter areas of the wall, the painter evoked not only the strength of the light which illuminates its surface but their crusty texture produced by repeated coating of lime which necessary to maintain the walls clean, fully reflective and hygienic. Minor cast shadows, instead, were often painted with thin, semi-transparent layers of darker paint in order to suggest their insubstantial nature. The contours, tones and shapes of the shadows cast by the widows, painting-within-paintings, maps etc. provide more precise information about the intensity and direction of the light as well as information about the morphological characteristics of the objects which cast them.

The rustic floor

In keeping with the humble kitchen setting, the pavement of the floor shows no fancy ceramic or marble tiles, but a simple bare floor with a rustic footwarmer and a few pieces of what appear to be bread crumbs and loose straw scattered about, most likely from a matress used for sleeping in the colder months. Modern art-goers remain transfixed by the light and seemingly monumental character of the picture. However, the humble subject matter of the painting was not accepted by all art lovers of Vermeer's time.

Although it is hard to understand today, in the 17th century, there existed a clearly defined hierarchy of subject matter in painting that was based on a conceptual distinction between art that was produced by an intellectual effort to "'render visible the universal essence of things" (imitare in Italian) and that which merely consisted of "mechanical copying of particular appearances" (ritrarre). Gerard de Lairesse, a well-known art theoretician of the time, held that appropriate subjects were not those extracted from the artist's imagination or personal circumstances, such as those seen in Vermeer's interior paintings, but from texts: the Bible and Classical literature and mythology. Paintings of street peddlers, cuckolded husbands, kitchen maids, unruly country bumpkins and buxom courtesans would not do, despite the fact that they were eagerly collected by Dutch art buyers, giving birth to a veritable army of highly specialized Dutch painters.

One of the most popular categories of painting was the kitchen scene, which had been developed in the Southern Netherlands in the late part of the sixteenth century and had reached an unimaginable level of technical refinement. It is hard to understand if Vermeer's humble milkmaid owes anything to the great Flemish tradition, but the artist must have been aware not only of classicist prescription but of the fact that in the Netherlands, kitchen maids were often associated with licentious conduct.

Despite their popularity, De Lairesse recommended that paintings of kitchens should only be hung in kitchens because of their inherently vulgar subject matter. But evidently, Dutch buyers thought differently. Of seventy-two kitchen paintings described in specific rooms in Dutch inventories from 1600 to 1679, only three were found in kitchens. Moreover, Vermeer's humble milkmaid was sold at a posthumous now-famous Dissius auction held in Amsterdam for the considerable sum of 175 guilders: more than any of the 21 Vermeer's at the same auction, except for the View of Delft, which is many times larger than The Milkmaid.

special topics

- What is the milkmaid cooking?

- Milk, cheese, and cleanliness

- Dutch bread

- Vermeer's big mistake?

- Dutch women in the 17th century

- The right time to enter the art market

- What was Vermeer's kitchen like?

- Emblematic meaning in painting

- A missing clothes basket

- Who posed for the milkmaid?

- The painting's history

- Vermeer's palette

- Whitewashed walls

- Dutch bakeries

- Listen to period music

The signature

No signature appears on this work.

(Click here to access a complete study of Vermeer's signatures.)

Dates

1660–1661

Albert Blankert, Vermeer: 1632–1675, 1975

c. 1658–1660

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., The Public and the Private in the Age of Vermeer, London, 2000

c. 1657–1658

Walter Liedtke, New York, 2008

c.1658–1659

Wayne Franits, Vermeer, 2015

(Click here to access a complete study of the dates of Vermeer's paintings).

Technical report

The closed, plain-weave linen still has its original tacking edges. The thread count is 14 x 14.5" per cm². The canvas was relined with wax/resin in 1950 over an existing paste lining.

The ground is a pale brown/gray, containing chalk, lead white and umber. Apart from a strip above the milkmaid's head along the upper edge of the painting, there is a dark underpainting in the background. Infrared reflectography shows broad, black undermodeling in the shadows of the blue apron. A pinhole with which Vermeer marked the vanishing point of the composition is visible in the paint layer above the right hand of the maid.

A red lake glaze is used as an underpaint in the flesh color of the maid's right hand. It is followed by an ocher layer in the shadows, and a white layer followed by a pink layer in the highlights. Several areas were painted wet-in-wet: the glazing bars, the maid's white cap and the details of her yellow bodice. The still life is richly textured with a combination of glazing, crumbling and thick impasto. The bright blue edge to the maid's skirt is created by the luminosity of the underlying white layer.

* Johannes Vermeer (exh. cat., National Gallery of Art and Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis - Washington and The Hague, 1995, edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr.)

Provenance

- (?) Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven, Delft (d. 1674); (?) his widow, Maria de Knuijt, Delft (d. 1681);

- (?) their daughter, Magdalena van Ruijven, Delft (d. 1682);

- (?) her widower, Jacob Abrahamsz Dissius (d. 1695); Dissius sale, Amsterdam, 16 May, 1696, no. 2;

- Isaac Rooleeuw, Amsterdam (1696–1701);

- Rooleeuw sale, Amsterdam, 20 April, 1701, no. 7;

- Jacob van Hoek, Amsterdam (1701–1719);

- Van Hoek sale, Amsterdam, 12 April, 1719, no. 20;

- Pieter Leendert de Neufville, Amsterdam (before 1759);

- Leendert Pieter de Neufville, Amsterdam (1759–1765);

- De Neufville sale, Amsterdam, 19 June, 1765, no. 65, to Yver;

- Dulong sale, Amsterdam (H. de Winter and J. Yver), 18 April, 1768, no. 10, to Van Diemen;

- Jan Jacob de Bruyn, Amsterdam (1781);

- De Bruyn sale, Amsterdam, 12 September, 1798, no. 32, to J. Spaan;

- Hendrik Muilman sale, Amsterdam, 12 April, 1813, no. 96, to J. de Vries for Van Winter;

- Lucretia Johanna van Winter (Six van Winter, after 1822), Amsterdam (1813–1845);

- Jonkheer Hendrik Six van Hillegom, Amsterdam (1845–1847);

- Jonkheers Jan Pieter Six van Hillegom and Pieter Six van Vromade, Amsterdam (1847–1899/1905); Six van Vromade heirs;

- purchased in 1908 by the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (inv. A2344).

Exhibitions

- Amsterdam 1872

Katalogus der tentoonstelling van schilderijen van oude meesters

Arti et amicitiae

21, no. 142 - Amsterdam 1900

Catalogus der verzameling schilderijen en familieportretten van de heeren jhr. P. H. Six van Vromade, Jhr. J. Six en jhr. W. Six

Stedelijk Museum

17, no. 70 - Paris 1921

Exposition hollandaise. Tableaux, aquarelles et dessins anciens et modernes

Jeu de Paume

10, no. 105 - London 1929

Exhibition of Dutch Art, 1450–1900

Royal Academy of Arts

144, no. 302, and pl. 77 - Amsterdam 1935

Vermeer tentoonstelling ter herdenking van de plechtige opening van het Rijksmuseum op 13 July, 1885

Rijksmuseum

27, no. 163, and ill. - Rotterdam 1935

Vermeer, oorsprong en invloed. Fabritius, de Hooch, de Witte

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

35, no. 81 and ill. 62 - New York 1939

Masterpieces of Art. New York World's Fair

194–195, no. 398 and pl. 71 - Detroit 1939

Masterpieces of Art from Foreign Collections. European Paintings from the New York and San Francisco World's Fairs

Detroit Institute of Arts

19 and ill. 52 - Detroit 1941

Masterpieces of Art from European and American Collections. Twenty-Second Loan Exhibition of Old Masters

The Detroit Institute of Arts

19 and ill. 62 - Montreal February 5–March 8, 1942

Loan Exhibition of Masterpieces of Painting (Exposition de chefs-d'oeuvre de la peinture)

Museum of Fine Arts, Art Association - New York October 8–November 7, 1942

Paintings by the Great Dutch Masters of the Seventeenth Century

Duveen Galleries

87, no. 67 and ill. - Chicago November 18–December 16, 1942

Paintings by the Great Dutch Masters of the Seventeenth Century

Art Institute of Chicago

64, no. 41 and ill. - Zurich 1953

Hollander des 17. Jahrhunderts

Kunsthaus

72, no. 171 and ill. 28. - Rome January 4–February 14, 1954

Mostra di pittura olandese del seicento

Palazzo delle Esposizioni

90, no.176 and ill. 31, as "La cuciniera" - Milan February 29–April 25, 1954

Mostra di pittura olandese del seicento

Palazzo Reale

no. 176 and ill. no. 31, as "La cuciniera" - The Hague June 25–September 5, 1966

In het licht van Vermeer

Mauritshuis

no. 2 and ill. - Paris September 24–November 28, 1966

Dans la lumière de Vermeer

Musée de l'Orangerie

no. II and ill. - The Hague March 1–June 2, 1996

Johannes Vermeer

Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis

108–113, no. 5 and ill. (not shown in Washington) - Amsterdam 2000

The Glory of Golden Age: Dutch Art of Seventeenth Century

Rijksmuseum

197, no. 136 and ill. - New York March 8–May 27, 2001

Vermeer and the Delft School

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

no. 69 - London June 20–September 16, 2001

Vermeer and the Delft School

National Gallery

no. 69 - Tokyo June 26, 2007–September 26, 2007

"The Milkmaid" by Vermeer and Dutch Genre Painting: Masterworks from the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

The National Art Center

48, no. 1 and ill. - New York September 9–November 29, 2009

Vermeer's Masterpiece '"The Milkmaid'"

The Metropolitan Museum of Art - Paris February 22–May 22, 2017

Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry

Musée du Louvre - Tokyo October 5, 2018 –February 3, 2019

Making the Difference : Vermeer and Dutch Art

Ueno Royal Museum - Amsterdam April 1–May 15, 2022

Dutch Heritage Amsterdam

Hermitage Amsterdam - Amsterdam February 10– June 4, 2023

VERMEER

Rijksmuseum

no. 7 and ill.

(Click here to access a complete, sortable list of the exhibitions of Vermeer's paintings).

Milk, cheese & cleanliness

Still life with Glass, Cheese, Butter and Cake

Floris Gerritsz. van Schooten

First half of the 17th century

Oil on panel

Private collection

It is well known that the Netherlands, and particularly its women, had an international reputation for cleanliness. Between 1500 and 1800, numerous travelers reported the habit of housewives and maids who meticulously cleansed the interior and exterior of their households. Why so? Historians Bas van Bavel and Oscar Gelderblom have argued that "it was the commercialization of dairy farming that led to improvements in household hygiene. In the 14th century, peasants but also urban dwellers began to produce large quantities of butter and cheese for the market. In their small production units, the wives and daughters worked to secure a clean environment for proper curdling and churning."

The two historians have estimated that at the turn of the 16th century half of all rural households and up to one-third of urban households in Holland produced butter and cheese, for which hygiene is of paramount importance. Cows have to be milked with proper care to prevent the transmission of diseases between them. Small farmers may have to save up raw milk for several days before they can start dairying. Without the use of modern equipment, the production of butter and cheese requires several days.

A German professor of veterinary medicine noted that cleanliness in stables was very important for dairying which explained why Dutch butter was so much better than German butter. Dutch milkmaids were noted for their hygiene and the speed with which they churned. Presumably, such good care would be able to produce butter of equal quality and the higher price this fetched would compensate for their extra efforts.

Even the eyes of the most sophisticated viewers rarely fail to be mesmerized by the glistening stream of white liquid issuing from the pitcher in Vermeer's Milkmaid. But milk was rarely drunk in urban areas because it was likely to spoil before it could be consumed.

In many historical references, the Netherlands' emphasis on cleanliness wasn't solely a product of dairy farming. Urban development, the growth of trade and advancements in science and medicine all contributed to a cultural shift towards hygiene. The canals, for instance, were not just for transportation. They played a vital role in waste disposal, leading to cleaner streets and reduced disease spread. This culture of cleanliness and orderliness could also be seen in their well-maintained public squares, gardens and homes.

Historical records from the time show travelers expressing admiration for the Dutch attention to cleanliness. A prominent French traveler once remarked that the streets of Amsterdam were so clean, one could eat off them. This wasn't just hyperbole; it underscored a genuine appreciation for Dutch cleanliness standards that surpassed much of Europe at the time.

The Dutch Golden Age, spanning the 17th century, also saw rapid advancements in science and art. This period of cultural, scientific and artistic proliferation further influenced the Dutch way of life, with an emphasis on precision, attention to detail and a greater understanding of the environment.

In all, while dairy farming might have played a pivotal role in highlighting the importance of hygiene, the story of Dutch cleanliness is multifaceted, rooted in the nation's socio-cultural evolution over centuries.

Dutch bread

Still Life (detail)

Pieter Claesz.

1633

Oil on oak panel, 64 x 88.5 cm.

Museum Schloss Wilhelmshöhe, Kassel

Although the northern Netherlands' soil proved too wet for large-scale wheat farming, the Baltic grain trade allowed the nation ample access to this staple crop. By the 17th century, the Dutch virtually controlled wheat and rye production in Poland, East Prussia, Swedish Pomerania and Livonia. Silos in the Dutch cities of Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Middelburg stored large grain surpluses, thereby safeguarding against price fluctuation and bread shortage. As a result of these government-enforced measures, the Dutch enjoyed greater food stability than their counterparts throughout much of 17th-century Europe.

At least two meals per day in a typical Dutch household included sliced bread, usually topped with butter or cheese. The more affluent enjoyed herenbrood—"white" bread made from wheat flour—on a regular basis, while the less prosperous typically depended on semelbrood, "black," rye-kernel bread, for their daily starch. During times of extreme food scarcity, some peasants turned to bread made from ground chestnut meal.

Once, Van Buyten showed the French aristocrat Balthasar de Monconys one of his works by Vermeer, which he estimated as being worth 600 livres. After the artist's death, he received two more paintings from Vermeer's wife, Catharina Bolnes, as a security for the debt for bread of more than 600 guilders.

The economist and art historian John Michael Montias reckons that this sum covered about 8,000 pounds of white bread at the prices of the time, roughly three years' worth of supplies for a household of that size. When Vermeer died, he left his wife with 11 children.

The influence of bread within Dutch society went beyond mere sustenance. Bread was symbolic of Dutch industriousness and innovation. Their mastery over trade and their ability to control significant portions of the grain market testified to their commercial prowess. The bakeries and bread-making processes became symbols of a flourishing Dutch domestic economy. Dutch painters, inspired by the daily lives of their countrymen, frequently painted scenes of domesticity where bread, alongside cheese or wine, featured prominently. It wasn't just a source of nutrition but also an emblem of the home and hearth. Bread, being a staple, played a crucial role in societal rituals and traditions. Special bread was baked for festivals, marriages and other significant occasions. In many ways, the story of bread in the 17th-century Netherlands is not just about food. It's about commerce, art, society and tradition all intertwined.

Dutch women in the 17th century

Lady at her Toilette (detail)

Gerrit ter Borch

1660

Oil on canvas, 76.2 x 59.7 cm.

Institute of Arts, Detroit

Jonathan Israel, a historian of the Golden Age of the Dutch Republic, notes that "no aspect of Dutch freedom in the golden age struck contemporaries, particularly foreigners, more than that enjoyed by women of all classes and types. Everyone agreed that in Dutch society, wives were less subservient to their husbands than elsewhere." Simon Schama goes even further than Israel by asserting that "the Netherlands possesses one of the oldest and richest traditions of feminism in Europe."

Regrettably, first-person descriptions of Dutch women, whether in the form of books, letters, or diaries, are exceedingly rare. The sole noteworthy autobiography was penned by Anna Maria van Schurman, an extraordinary, highly educated woman who excelled in visual arts, music and literature, as well as being proficient in 14 languages. Otherwise, we know little about the actions of real Dutch women.

We understand quite well how Dutch women were expected to conduct themselves, at least in theory. Conduct books, child-rearing manuals and various moralistic writings, second in popularity only to the Bible, speak loudly and clearly. First and foremost, women were expected to find complete fulfillment through marriage, child-rearing and housekeeping. The home was the designated place for the woman, and it was also the safest place, preventing succumbing to temptation. Domestic virtue was not only seen as the prime regulator of male/female relationships but also as one of the keys to the stability and prosperity of the Dutch nation itself. Perhaps no other painting of the Golden Age conveys this quintessential value as convincingly as Vermeer's Milkmaid, if not the more discreet Lacemaker.

However, in daily life, Dutch women must not have blindly adhered to the strict guidelines laid down by the moralists. In a surprising number of eyewitness accounts, particularly those of foreign visitors, we encounter an entirely different kind of women, especially outside the domestic setting.

An auspicious time to enter the art market

Book and Picture Shop

Salomon de Bray

1628

76 x 76 mm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

When Vermeer began producing his genre paintings in the late 1650s, he could not have started his career at a more opportune moment. The Dutch economy virtually flourished after the cessation of hostilities with Spain in 1648; indeed, the nation's economy would reach its peak within a few short years.

After a few initial attempts at history painting in the mid-1650s, Vermeer abruptly changed his focus to fully dedicate his attention to his now-famous genre interiors, a new artistic style pioneered by Dutch painters decades earlier.

Though the prevailing notion suggests that genre pictures capture essential glimpses, or "snapshots," of daily life, in reality, they depict only a small portion of daily experiences in Dutch living. For instance, individuals engaged in intellectual or entertaining activities far outnumber those shown at work. Despite the lengthy and harsh wars that the Dutch had to constantly wage to preserve their independence and prosperity, very few actual battle scenes were painted. Soldiers were predominantly portrayed in elaborate military attire as they participated in harmless activities like card-playing or mercenary lovemaking. And while countless ships and marinescapes attest to the Dutch reliance on maritime trade, the sailors are usually depicted with a few skillful brushstrokes as they move about the intricate riggings and naval fixtures. They are seldom shown up close while working on specific tasks or given a recognizable face.

Though the widespread distribution of paintings in the Netherlands might have been exaggerated by contemporary accounts, a considerable portion of the population could indeed afford at least a painting or two. In an era when average working-class wages totaled around 500 to 700 guilders, a high-quality genre painting could be acquired for 10 guilders or even less. One tronie (a single head) by Vermeer, purchased by a Danish sculptor, was valued at 10 guilders, although his more complex works must have commanded much higher prices. A prosperous Delft baker once mentioned that a single-figure work by Vermeer was valued at the astounding sum of 600 guilders.

Emblematic meaning of the Dutch maid

Amoris divini emblemata (titlepage)

Otto van Veen

1615

None of the sitters, including the young woman who posed for The Milkmaid, have ever been identified, even though there persists a sentimental tendency to associate her with a maid of the Vermeer household, Tanneke Everpoel. Whether she is Tanneke or not, the painting was certainly not intended as a portrait.

In Dutch emblematic and popular literature, maids were often depicted in their subservient role and as a threat to the honor and security of the home, the center of Dutch life. In effect, maids were considered the most dangerous women of all. Kitchen maids, and especially milkmaids, were known for their sexual availability. Nonetheless, some of Vermeer's contemporaries, like Pieter de Hooch or Michael Sweerts, portrayed maids in a more neutral role. Certainly, Vermeer's empathetic interpretation of this maid stands virtually alone if not for a few pictures by Sweerts who had a predilection for painting characters who rarely appeared in formal portraits of the time. Sweerts' Young Maid Servant is a rare example of a dignified treatment of a specific individual from the lower class of Dutch society.

A missing clothes basket

An infrared radiography image reveals that the subtle tonal shift (pentimento) behind the milkmaid's red skirt indicates the presence of a large and noticeable clothes basket, which Vermeer later painted over. This instance was not the only occasion when Vermeer simplified his compositions by removing substantial objects from his paintings. In A Maid Asleep, a dog previously occupied the open doorway, and a cavalier stood in the adjoining room. Certain critics speculate that these elements were eliminated to more accurately emphasize the symbolic significance of the works.

The most common explanation for the disappearance of the basket is the potential enhancement of aesthetic balance within the composition. However, scholar Paul Taylor recently asserted, "contemporary art theoretical texts written in Dutch provide no evidence that 17th-century Dutch and Flemish artists tried to achieve an overall balance of design. Although Dutch authors wrote at some length about composition, ordinantie, they never suggested that 'visual balance' was part of the concept as they understood it." Essentially, "composition was first and foremost the attempt to tell a story clearly and logically."

Therefore, it's likely that Vermeer omitted the basket to clarify the narrative of the painting rather than to enhance its formal balance. Taylor suggests, "The maid would have to be a rather heedless person if she gathered all the laundry of the house, took it down to the kitchen, and then left it on the floor while she made a meal with bread and milk."

A Fire Basket

Jacobus Dorsman

c. 1800

Pen and watercolour, 19 x 15.6 cm.

Universitaire Bibliotheken Leiden, Leiden,

However, recent technical investigations carried out at the Rijksmuseum have clarified that what was formerly understood as a clothes basket was, in fact, a different object with a different function: a vuurmand (fire basket). This curious object served as a portable heating device, especially beneficial for women in childbed. Thanks to its tall, domed woven structure, it also facilitated the drying of swaddling clothes. A metal container for holding hot coals was placed at the very bottom. The object was later covered with white-washed wall, Delftware tiles, anda a foot stove, shifting the focal point of the scene to the act of pouring milk.

Moreover, affixed to the plaster wall, in the right-hand portion of the composition, at the height of the girl's head, Vermeer initially sketched in a shelf, a plank of wood, adorned with hanging lidded jugs hanging from knobs. A similar ensemble can be found in the cooking kitchen of the doll's house of Petronella Oortman, c. 1690-1710, in the Rijksmuseum. A preliminary sketch in black paint depicts a shelf with several jugs hanging on hooks. The jug holder, a plank of wood with knobs, would have been used in 17th-century kitchens for hanging ceramic jugs by their handle. Vermeer had a similar version in his home pantry.

Who posed for the milkmaid?

A Young Maid Servant

Michael Sweerts

c. 1660

Oil on canvas, 61 x 53.5 cm. Fondation Aetas Aurea

Vaduz, Liechtenstein

Documents in the Delft archives show that a certain Tanneke Everpoel lived with Maria Thins, Vermeer's mother-in-law, and the Vermeer-Bolnes family in 1663.

Maria's son, the irascible Willem Bolnes, stoked by his ogre father, tormented Maria and her daughter while they lived in Gouda. After Maria's divorce, when she had moved with her daughter to the more tranquil Delft in the hopes of starting a fresh new life far from her ogre husband and deranged son, Willem continued his troublesome behavior. Despite forbearance on the part of Vermeer's wife, Willem turned up on several occasions in 1663 at the house on the Vermeer residence at Oude Langendijck and caused trouble. According to a legal document, several witnesses, including Tanneke, testified that Willem had created a violent commotion, attracting people outside to come to the front door and listen. Willem swore at his mother, calling her "an old popish swine, a she-devil and other such ugly swearwords that, for the sake of decency, must be passed over," and pulled a knife on his mother and tried to stab her. With a long history of violence, Willem also committed acts of violence against Catharina, threatening on one occasions to beat her with a stick with a pointed metal cap, even though she was in the last stages of pregnancy. The witness Tanneke Everpoel testified that Willem would actually have beaten his sister had she not intervened herself.

The witnesses were in agreement that Willem was not entirely in his right mind. And indeed, his violent and abusive acts echoed the appalling behavior of his father toward his mother twenty years earlier. Reynier Bolnes, at that time, had forced his wife to eat all her meals alone; he had constantly insulted her and had also beaten her with a stick when she was pregnant. Such a pattern of violent acts, repeated from one generation to the next, is a familiar phenomenon in our day as well.

Tanneke would probably have been responsible for most of the shopping, which would have required no small amount of physical strength. The Thins domicile housed herself, Vermeer, his wife, and Vermeer's ever-expanding family. It appears that she was so well-liked that she was listed as a beneficiary in one of Maria Thins' wills.

In Dutch emblematic and popular literature, maids were often depicted in their subservient role and as a threat to the honor and security of the home, the center of Dutch life. They were considered the most dangerous women of all. Kitchen maids, and especially milkmaids, were known for being sexually available. However, some of Vermeer's contemporaries, like Pieter de Hooch, began to depict maids in a more neutral role. Certainly, Vermeer's empathetic and dignified interpretation of this maid stands almost alone, if not for a few pictures by Michael Sweerts, who had a preference for painting characters rarely found in formal portraits of the time. Sweerts' Young Maid Servant provides a rare example of treating a specific individual from the lower class of Dutch society with dignity.

The painting's history

Throughout its history, the small painting titled "The famous Milkmaid, by Vermeer of Delft, artful" has enjoyed renown. Its 1719 title already speaks volumes, indicating the familiarity of "Vermeer of Delft" among Amsterdam's connoisseurs.

When Jacob van Hoek, an Amsterdam merchant-collector, passed away in 1719, the painting formed part of his estate. Likely obtained at the 1701 Rooleeuw auction, the Mennonite merchant Isaac Rooleeuw (c. 1600-1710) had purchased this "famous Milk Maid" for 175 guilders along with "Woman Holding a Balance" at the 1696 Dissius sale. Rooleeuw's acquisitions highlighted his appreciation for Vermeer's style, with his collection eventually being sold due to bankruptcy shortly after his acquisition.

Pieter Leendert de Neufville, an Amsterdam merchant, became the first known owner of The Milkmaid after Jacob van Hoek. Despite a 1730 bankruptcy, his collection endured and was later inherited by Leendert Pieter de Neufville, who faced further misfortune in business. In 1798, the painting was acquired by J. Spaan, possibly acting for wealthy Amsterdam banker Hendrik Muilman).

Jan Rinke, "The Minister P Rink and the Milk

Maid from the Six Collection," cartoons from Her

Vaderland, 9 November 1907.

Following Muilman's 1813 death, his impressive collection of paintings, including Vermeer's Lacemaker, was auctioned. The painting found a new home with Jonkvrouwe Lucretia Johanna van Winter, a prominent Dutch woman collector. The renowned "Creejans" van Winter had already inherited significant artworks, including The Little Street, which she brought into her marriage with Jonkheer Hendrik Six van Hillegom. Traveling in Holland in 1781, the successful English portrait painter Joshua Reynolds saw The Milkmaid and was impressed by the fidelity of Vermeer's artistic vision, wrote (to Edmund Burke) that "Dutch pictures are a representation of nature just as it is seen in a camera obscura."

The Six Collection, featuring The Milkmaid, was a major attraction in 19th-century Amsterdam. Professor Jan Six, a descendant of the owners, reflected on the collection's enduring popularity. Despite public resistance, the painting was acquired by the Dutch State. The issue of acquiring the Six Collection's artworks sparked debate through Frits Lugt's brochure. The Director of the Mauritshuis, Abraham Bredius, and parliament ultimately favored preserving national heritage, leading to the painting's acquisition.

Bredius was convinced that the American magnate-art collector J.Pierpont Morgan desired the painting. After significant dispute in the press, the matter found resolution in parliament. The opposition, led by socialist Troelstra, advocated for modern art acquisition, while Victor de Stuers, a member of the Dutch parliament and leading defender of Dutch cultural heritage, advocated maintaining the painting in the Netherlands, at any cost The parliamentary majority aligned with the latter perspective, resulting in the purchase of The Milkmaid. Cartoons humorously depicted "Holland's best-looking milkmaid" rejecting her American suitor, "Uncle Sam." On January 13, 1908, thirty-nine artworks from the Six Collection were displayed in an easterly cabinet of the Rijksmuseum.

Vermeer's palette

Like his contemporaries, Vermeer possessed a limited number of pigments compared to those available to the modern artist. Throughout his career, he appeared to use no more than 20 different pigments, though he rarely employed more than 10 regularly. The only divergence in Vermeer's palette was his preference for the costly natural ultramarine, crafted from crushed lapis lazuli and imported from Afghanistan through Venice. Other painters opted for the more common and cheaper azurite. While The Milkmaid shares much with the technique seen in the previous Officer and Laughing Girl, it boasts one of the most brilliant color schemes in his works. Even though the use of brilliant pigments such as lead-tin yellow, vermilion and natural ultramarine are used copiously, the use of strong local color is not sufficient in itself to explain the exceptional luminosity in this piece.

Regardless, artists during Vermeer's time typically organized their palettes differently each day, including only the necessary pigments for the day's tasks. After a monochrome underpainting adequately outlined basic forms and lighting, each section was refined individually, one at a time.

White-washed walls

Although a number of painters working in Delft, such as Anthonie Palamedesz and Pieter de Hooch, prominently featured white-washed walls in the background of their interior scenes, none seem as real as those of Vermeer. Even though the wall behind the standing milkmaid is virtually featureless, it stands as one of the painter's most remarkable technical achievements, which can only be appreciated when one stands in front of the real painting.

A Merry Company

Anthonie Palamedesz.

1634

Oil on canvas, 51 x 83 cm.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

The humble walls illuminated by daylight of varying intensities present one of the most challenging pictorial problems in Vermeer's oeuvre. When comparing similar representations of walls by his contemporaries to those of Vermeer, one cannot help but notice the diverse tones of gray pigment used. Instead, in Vermeer's renderings, these same or similar tones appear inseparable from the illusion of the natural light as it rakes across the uneven texture of the plastered surface. Surprisingly, the palette Vermeer employed for painting the wall in this piece is simple yet effective: white lead, umber and charcoal black. This uncomplicated formula for painting white objects was widely known, but among contemporary genre painters, perhaps no artist was more effective in its application than Vermeer.

Whitewashing served several fundamental purposes in 17th century Netherlands, reflecting both cultural values and practical considerations. Firstly, it was closely tied to hygiene and cleanliness. The Dutch of that era placed a strong emphasis on cleanliness, and whitewashed walls contributed significantly to creating a fresh and orderly atmosphere within indoor spaces. In fact, the Dutch were renowned for their cleanliness then as today, and Delft, where Vermeer lived and worked all his life. Foreigners often find it amusing to learn that the earlier Dutch word schoon stands for both "beautiful" and "clean."

Additionally, whitewashed walls played a role in optimizing the available natural light. Given the often overcast weather conditions in the Netherlands, effective use of light was crucial. Whitewashed surfaces were adept at reflecting light, enhancing the overall brightness of interiors.

Beyond aesthetics, however, whitewashing had health-related benefits. The belief that it possessed disinfectant properties was prevalent. Lime, a common component of whitewash, had antimicrobial qualities that were thought to help curb the spread of germs, contributing to a healthier indoor environment, important to the making beer or cheese, which were commonly done at home.

Moreover, whitewashing was practical from an economic standpoint. It offered an affordable means of maintaining and revitalizing the appearance of walls. It served as a protective layer, guarding against moisture and wear, which prolonged the lifespan of plastered surfaces.

Whitewash consisted of a mixture of water, lime and pigment. Lime was obtained by heating limestone, yielding a fine powder that, when combined with water, formed a paste. The lime paste was blended with water in a sizable container, creating a solution of slaked lime. To achieve various shades of whitewash, pigments like clay or charcoal could be incorporated. The resulting whitewash mixture was then spread onto walls using brushes, rollers, or manual application. It was layered thinly onto the plastered surface. As it dried, the whitewash solidified into a durable coating.

Missing objects

The Shoemaker's Shop (detail)

Quiringh Gerritsz. van Brekelenkam

Oil on panel, 59.4 x 82.6 cm.

Norton Simon Art Foundation, Pasadena CA

From the outset of his career, Vermeer spared no pains to achieve the most powerful, communicative image possible making scores of major and minor alterations in the composition during the painting process. It may come as a surprise that the present work, whose design is so stark and so solid as to seem inevitable, was achieved after considerable reworking. In fact, two large objects that were part of the original composition were painted out by Vermeer himself. In the lower-left behind the maid's skirt there once stood a large, open clothes basket with laundry issuing from it. A large rectangular object whose horizontal form suggests that it may have been a mantelpiece once stood behind the maid. The Delft wall tiles and the footwarmer were, instead, afterthoughts.

What is the milkmaid cooking?

A Kitchen

Hendrick Sorgh

c. 1643

Oil on panel, 52.1 x 44.1 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

To truly grasp the exceptional impact of this canvas, one that leaves a lasting impression on anyone fortunate enough to behold it, delving into Vermeer's intentions can be enlightening. Curiously, despite the extensive scrutiny Vermeer's Milkmaid has undergone, the question of her actual activity has largely been overlooked by art historians. While it's evident that she is pouring milk in a contemplative manner, the underlying reason has rarely been explored. Art historian Harry Rand has researched this matter, and although not universally accepted, his theory is expounded upon below.

Primarily, it's important to recognize that the woman depicted by Vermeer isn't the proprietor of the household; she is, in fact, a common servant. This distinction is crucial, as she shouldn't be confused with other attendants, referred to as kameneir, who catered to the personal needs of upper-class women while also acting as their protectors.

Vermeer's unassuming maid is in the process of slowly pouring milk into a stout earthenware vessel known as a Dutch oven. The vessel's recessed rim indicates its design for accommodating a lid, rendering it airtight for baking purposes. These Dutch ovens were typically employed for extended, gradual cooking, and they were fashioned from iron or, as seen in this painting, ceramic. Rand's interpretation centers on the broken pieces of bread before her in the still life. This suggests she may have already prepared custard, with the bread and egg mixture now being soaked. The milk is then poured over the concoction to submerge it, as without liquid simmering during baking, the upper crust of the bread would dry out unappetizingly instead of forming the delectable upper layer of the pudding. The meticulousness with which the milk is poured stems from the necessity of precise measurements and thorough mixing for a successful bread pudding.

Rand's hypothesis finds further support in the presence of a foot warmer with smoldering embers on the floor. This indicates that the maid's kitchen lacks proper heating. In well-to-do households, it was common to have two kitchens: one for "hot" daily cooking like meats and bread, and a "cold" kitchen reserved for creating pastries and confections. The cold kitchen facilitated the melting of crucial butter and provided ample time for incorporating it into dough or crusts.

Consequently, Vermeer's portrayal transcends being a mere visual depiction of a commonplace scene; it conveys ethical and societal values. It captures a precise instant in which the household maid is diligently engaged with ordinary culinary ingredients, reviving otherwise inedible stale bread and transforming them into a fresh and enjoyable creation. Her composed demeanor, unpretentious attire and careful preparation of food subtly and eloquently communicate one of the prevailing virtues of 17th-century Netherlands: domestic rectitude.

Of course, the maid's endeavor might have been simpler than Rand's pudding, possibly involving a basic dish like pap for young children, crafted from bread and milk, ingredients unmistakably present in Vermeer's composition.

Dutch bakeries

The Bakery

Job Berckheyde

Oil on canvas

c. 1681

Worchester Art Museum, Massachusetts

It is more likely than not that the bread in Vermeer's Milkmaid was not made at home but purchased at a bakery, perhaps from one of Vermeer's collectors, Hendrick van Buyten, who owned the largest bakery in Delft. It is known that the Vermeer family had accumulated a considerable debt for bread. Following the death of her husband, Catharina, Vermeer's wife, settled this debt with Van Buyten by giving him a painting by her late husband. This gesture was notably sympathetic toward the painter's widow, considering the significant amount owed to the baker was 617 guilders, a sum sufficient to purchase a modest Dutch house.

The number of bakeries in 17th-century Holland was significant, and like most merchants, bakers typically set up their operations in their own homes. Due to the fire threat their ovens posed to neighboring properties, they often resided and conducted business in stone buildings.

Rye bread was the primary food source for the populace. The price and quality of the rye bread were strictly regulated, though often considered low by the bakers. Attempts were made to decrease the bread's size, leading the authorities to appoint official controllers—certainly not popular figures—to measure and weigh the bread in stores.

In addition to common rye bread, bakers made fine bread of various qualities and flavors. Regulations for white bread and other luxury bread types were not as stringent as those for rye bread. Bread bakers were prohibited from producing biscuits, pies, or pastries. Since 1497, the guild had divided, with each specialty having its dedicated guild.

In a work by Job Berckheyde, a baker is depicted blowing a horn to herald his fresh batch of bread, rolls and pretzels, signaling they are ready for purchase.

Listen to period music

![]() Contredanse [1.16 MB]

Contredanse [1.16 MB]

Iep Fourier, hurdy-gurdy

http://vls.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iep_Fourier

From the album Speelman, Gij Moet Strijken

With kind permission by Davidsfonds, Belgium

http://www.davidsfonds.be/

Vermeer's big mistake?

Vermeer specialists have long been puzzled by a presumed anomaly of the perspectival construction of the clothe-covered table. Only recently has its real construction been understood. However, upon close examination, it can be shown that the table does not possess the expected rectangular top. Based on Keith Cardnell's geometric reconstruction of the tabletop's surface, various 17th-century Dutch art experts now concur that what we observe is actually half of the top of a 17th-century gateleg drop-leaf table, which, when opened, has an octagonal top. Such a piece of furniture would have been easily recognized by Vermeer's contemporaries.The defining characteristic of gateleg tables is their set of legs that swing out, like a gate, to support leaves (flaps or extensions) of the table. When not in use, these leaves can be dropped down, saving space and making the table much narrower.

In the diagram below, the white lines trace the visible orthogonals, which, correctly converging at the picture's vanishing point, inform the height of the painter's eye as he painted the picture. The yellow lines trace to the perimeter of the folded table.

What was Vermeer's kitchen like?

Dolls' house of Petronella Dunois

Anonymous

c. 1676

h c.200 cm x w c.150.5 cm x d c.56 cm.

Rijksmusuem, Amsterdam