Early Genre Works

- Early Genre Works and Life in Delft

- Vermeer and his Patron, Pieter van Ruijven

- A Maid Asleep

- Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window

- Breakthrough: The Milkmaid and Officer and Laughing Girl

- Camera Obscura

- Scenes of Haute Bourgeoisie Life

- Little Street

- The Pearl Pictures

- Violence

- The Music Lesson and The Concert

Whether Vermeer's initial impulse to be a history painter was encouraged by his master, his conversion to Catholicism or the hope of reaping princely commissions in the nearby Hague, he abruptly changed his subject matter and style of painting a few years after becoming a master in the Guild of Saint Luke.

Several factors may have influenced Vermeer's shift from his early ambitions as a history painter. Many of his contemporaries, like Nicolaes Berchem, Aelbert Cuyp, Paulus Potter, and Gabriël Metsu, began as history painters but later specialized in other genres, indicating a broader trend in the art world. Around 1656, Vermeer established relationships with collectors and potential patrons, notably Pieter Claesz van Ruijven and his wife, Maria de Knuijt. Exposure to artists like Gerrit ter Borch, who painted tranquil interiors, and Pieter de Hooch, who specialized in domestic scenes, showcased the rising demand for genre pieces over large history paintings. Vermeer's growing fascination with light and optics might have been fueled by Delft's scholarly and scientific community. It's noted that Vermeer's strengths were better suited to serene, introspective scenes rather than extroverted narratives. By 1656, he decided to leave history painting and large formats behind, possibly driven by market trends, personal preference, and a deeper exploration of the sacred within everyday life. Christian Tico Seife, "Early Ambitions: Vermeer’s Journey from Bible to Brothel," in VERMEER, ed. Pieter Roelofs & Gregor Weber, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2023, 132.

Perhaps he came to realize that although he was a talented painter of biblical and mythological scenes, his genius lay in the ability to convey a sense of dignity to images drawn from daily life. Except for the best paintings by Gerrit ter Borch (1617–1681), the intellectual depth and moral resonance of Vermeer's interiors find no parallel in Dutch genre painting.

Vermeer embarked on his career at an auspicious moment. The Dutch economy had surged with the end of the Eighty Years' War with Spain in 1648. The nation's economy would reach its peak within a few short years. Paintings of myriad styles and subject matters were bought and sold in staggering numbers. One historian estimated that from 5 to 10 million paintings were produced in the Gouden Eeuw (Golden Age) of Dutch art. Certainly, the fledgling artist must have known that he was pitting talents against some of the most skilled and highest-paid painters in the Netherlands, many of whom had been invited to work for prestigious European courts. Not only was competition fierce, but an aspiring genre painter also had to be skillful in navigating along the channels that might bring him into contact with elite Liefhebbers van de Schilderkonst (Lovers of the Art of Painting) who were both willing and able to purchase such costly luxury items (paintings of Dou, Ter Borch and Van Mieris could cost from 1,000 to 2,000 guilders—an average Dutch house might be worth 500 guilders). In effect, at that time, art galleries and public collections as we know them today did not exist, and painters were constrained to market their works by themselves.

Vermeer and his Patrons: Pieter van Ruijven and his wife, Maria de Knuijt

In November 1657, Vermeer and his wife Catharina were lent 200 guilders (to be repaid with a 4 1/2% interest) by Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven (1624–1674), a well-to-do Delft burger who was eight years older than Vermeer. Van Ruijven, who was a wealthy brewer's son, owned houses in Delft on the Oude Delft and the Voorstraat. He appears not to have had any other occupation than managing his investments. He married Maria Simonsdr. de Knuijt (1681), 1653. Maria de Knuijt was part of the Dutch Reformed Church while Van Ruijven adhered to a Remonstrant minority, barred from a political career in Delft. The couple probably lived in De Gouden Adelaar (The Golden Eagle), worth the considerable sum of 10,500 guilders. Van Ruijven and De Knuijt's estate was worth 24,829 guilders, making them one of the richest families in Delft.

Although it's been believed that Vermeer's 1657 debt to Van Ruijven and De Knuijt's 1665 bequest might have been related to painting deliveries, the depth of De Knuijt's connection to Vermeer as a primary client has only been recently emphasized. Both De Knuijt and Pieter van Ruijven likely were main patrons of Vermeer. Maria de Knuijt, as the lady of the house, would have been in charge of home furnishing, which included buying paintings. Paintings were seen as household items in the seventeenth century, with buyers often purchasing existing art or commissioning new works. A notebook from the Van Ruijven and De Knuijt household mentioned in their joint will titled "Disposal of my Paintings and other matters" further suggests De Knuijt's role as a collector, but its contents remain unknown. Moreover, De Knuijt, who was once a neighbor of Vermeer, lived a few houses away from the Mechelen inn, owned by her father. Though Maria was nine years older than Johannes Vermeer, she was close in age to his older sister, Gertruy, being only three years apart. Having grown up near the Vermeer family, Maria would have been familiar with the Vermeer siblings, possibly witnessing Johannes's childhood activities and interactions with his sister Gertruy.

Montias suggested that Van Ruijven's loan to Vermeer was an advance towards the purchase of one or more paintings. If this was not the case, chance has it that Van Ruijven and his wife, who could easily afford to buy expensive works of art, thereafter acquired a significant part, perhaps half, of Vermeer's lifelong production, or about twenty of the works. These paintings were later inherited by their daughter Magdalena and her printer husband Jacob Dissius (1653–1695). Both died young and their collection was sold in an Amsterdam auction on May 16, 1696. "The financial independence Vermeer enjoyed, partial and precarious as it was, gave him a greater opportunity to follow his own artistic inclination than most of his fellow members of the Guild, who had to adapt their art to suit market demand. He could paint fewer pictures than he might have had to, had he been forced to support his family exclusively from his art."John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 172. It seems apparent that Vermeer sold his paintings to a handful of affluent individuals who were capable of recognizing the extraordinary quality of his art, despite the fact that his fame was not nearly as widespread as that of the most renowned Dutch masters of the time. It appears likely that Vermeer's fame did not reach much farther than nearby The Hague or Amsterdam.

It has been speculated that Van Ruijven had modeled himself on his distant cousin Pieter Spiering (c.1594/7–1652, son of the famous tapestry weaver François Spiering), a rich art collector who had first option on the fijnschilder works of Gerrit Dou, the most sought-after Dutch painter of the time. By painting fine interiors for Van Ruijven, Vermeer may have wished to align himself with his patron's ambitious plans for "social rising." Van Ruijven had paid 16,000 guilders, an absolutely astronomical sum, to acquire land near Schiedam that brought with it the title of Lord of Spalant in 1669. If one is prone to biographical speculation, Vermeer's marriage into a much higher social level might be viewed as a part of a strategy to elevate his social and economic standing.

There is no indication that either Van Ruijven or his wife directly influenced the artist's choice of subject or style, although it is not out of the question. In the 1650s there already existed a strong market for exquisitely painted scenes of modern life. Nonetheless, Vermeer's pictures that ended up in the hands of the van Ruijven/De Knuit collection may be seen as a reflection of the painter's move upmarket, towards more sophisticated, burgerlijk (burgher-like) subject-matter. Many of the leisured young women in these pictures look more Oude Delft, where the Van Ruijvens resided, than humbler Voldersgracht. The Lord of Spalant's wife Maria and daughter Magdalena may have set the tone and even modeled for Vermeer.Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2002), 98-99.

Unfortunately, Van Ruijven would die three years earlier than Vermeer. After 350 years, the burgher's name is no longer confused among those of the many well-to-do Dutch of the time. Van Ruijven and his wife also owned works by the church painters Emanuel de Witte (1617–1692) and Simon de Vlieger (c. 1601–1653), two other painters who belonged to the so-called School of Delft.

The close relationship between Van Ruijven, his wife, and Vermeer is further demonstrated by a conditional bequest of 500 guilders to Vermeer in the testament of De Knuijt in 1665 (Vermeer's wife and children were not eligible if the painter predeceased them). Bequests to members outside one's family were a rarity. Van Ruijven also witnessed the testament of Vermeer's sister Gertruy in 1670.

Sometime in the mid-1660s, Vermeer painted his first genre interiors which in appearance have nothing to do with his inaugural history paintings or the boisterous Procuress.

A Maid Asleep

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1656–1657

Oil on canvas, 87.6 x 76.5 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Vermeer's first surviving domestic interior is the Maid Asleep (fig. 1), a view of a young maid who is either drunk, asleep, or suffering from melancholy. It is also the first painting to have entered into Van Ruijven's collection. Neither the theme nor the composition of the picture were not original. The composition can be easily traced to specific works of single-figure type of interiors pioneered by Nicolaes Maes (1634–1693) such as, A Young Woman Sewing (1655) and The Idle Servant (1655) (fig. 2). The Idle Servant supplied the budding painter with the young woman whose sleepy head is supported by her arm, the see-through doorway, and perhaps the warm palette dominated by comforting reds and browns, immediately abandoned by Vermeer after this picture.

In the Maid Asleep, every trace of technical bravado so conspicuously apparent in the Christ in the House of Martha and Mary has for some reason, evaporated. From a technical point of view, the surface of the canvas appears somewhat clogged. Modeling is labored and contours are tired, although the unattractive woolen effect of some key passages may owe to the work's modest state of conservation. The maid's fingers that are propped on the table are timidly rendered. The design on the flat surface of the carpet is confusing and the lion-head finials perched on top of the empty chair to the right lack sufficient definition. The lighting scheme is unusually erraticJudging by the fall of the soft shadows of the girl's face and figure we must assume that an open window was located more or less directly behind the viewer's shoulders where cool daylight filters in from above. However, the piece of clothing (?) which hangs between the Cupid and the door projects a shadow to its right which indicates a light source located outside the picture to the left-hand side of the painting. The soft shadow on the left-hand side of the white wine pitcher seems to indicate yet a third source of light somewhere to the right-hand side of the painting. While the rectangular background piece of white-washed wall behind the chair receives a discreet amount of light, the chair itself seems immersed in an inexplicable penumbra. The deep shadows cast on and to the right of the Cupid painting and the map cannot be explained at all. Although not at all impossible in reality, the light which comes from the left hand-side of the picture and rakes across the wall of the background room does not help the viewer interpret the disturbed lighting scheme of the foreground room where the maid sleeps. Perhaps the most attractive notation of light's activity is comprised by the two slender streaks of light paint which magically suggest the semi-gloss surface of the door's wooden frame. (various objects and architectural elements are lit from different directions) and the three-dimensional space, except for the see-through door that opens into another room, is almost as suffocating as the claustrophobic space of The Procuress. Perhaps the painting's most attractive passage is that of two slender streaks of light paint which suggest the soft glint of light on the semi-gloss surface of the door's wooden frame, an effect, however, which seems to have been borrowed from his less talented, but more inventive colleague, Pieter de Hooch.

Nicolaes Maes

1655

Oil on oak, 70 x 53.3 cm.

National Gallery, London

Clearly, the choice to depict contemporary subject matter in the refined style required Vermeer to rewire his technical, stylistic, and compositional approach to painting.

Despite the shortcomings of A Maid Asleep, the work prepared the young painter for one of his most interesting early works, Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (fig. 3), which may signal the artist's attention to the innovative Pieter de Hooch, who had settled in Delft and began to develop a new manner of portraying daily life, more objective than Nicolaes Maes. After marrying Jannetje van der Burch in 1654 and joining St. Luke's Guild in 1655, De Hooch may have worked at his brother-in-law Hendrick van der Burgh's studio until 1655. From the mid-1650s, both Vermeer and De Hooch began emphasizing domestic interior scenes in their artworks.

Thematically, the works of Vermeer and De Hoogh revolved around women in their everyday activities, the serenity of indoor domestic spaces, and the nuances of domestic life; both artists were also innovative in their use of linear perspective to render depth and space. Their paintings often showcase detailed architectural elements, furniture, and tiles, adding to the spatial depth of their compositions. Their meticulous attention to details, from fabric textures to intricate tile patterns, underscores their shared passion for capturing the minutiae of daily life. After relocating to Amsterdam around 1660, De Hooch continued painting scenes reminiscent of his Delft period, and it is possible that his works continued to influence those of Vermeer.

In essence, while it is hard to determine a direct influence without solid evidence, the fact that both worked in Delft during similar periods suggests that Pieter de Hooch and Johannes Vermeer may have shared a mutual artistic environment, each potentially influencing and drawing inspiration from the other.

Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1657–1659

Oil on canvas, 83 x 64.5 cm.

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

Despite the faulty composition of the Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (fig. 3) —the young girl is sunk too low on the picture plane—the sacramental dignity of the slender young figure makes it one of Vermeer's most poetic inventions. One art historian justly nominated it the most "beautifully imperfect"Walter Liedtke, Vermeer: The Complete Paintings (New Haven and London: Harry N. Abrams, 2008), 71. picture in Vermeer's oeuvre.

Unlike the majority of Vermeer's paintings, art scholars have had difficulties in uncovering a prototype for the Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window. The minuscule, hyper-detailed pictures of Frans van Mieris (1635–1681) are occasionally summoned to explain the single, standing-women motif (fig. 4), but Van Mieris' exasperated illusionism seems, in respects to Vermeer's broad manner, as an end in itself. However, the apparent tranquility of Vermeer's scene fails to suggest the momentous technical and intellectual struggle that was necessary to have brought such an ambitious work to completion. X-ray images reveal numerous major and minor alterations made during the painting process including the removal of a huge ebony-framed Cupid (which would eventually appear in two later works), the change of position of the girl's head, which originally looked away from the viewer, and the addition of the green trompe-l'œil curtain which conceals a large Roemer glass placed on the foreground table. Some critics have speculated that the young woman in profile, who resembles other women in Vermeer's paintings, was Vermeer's wife, Catharina. Having finally discovered his true "calling," the artist proceeded to slowly paint one masterwork after another.

Frans van Mieris the Elder

1661 - 1663

Oil on panel, 30 x 23 cm.

Berlin State Museums, Gemäldegalerie

Breakthrough: The Milkmaid and Officer and Laughing Girl

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1658–1661

Oil on canvas, 45.5 x 41 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In the late 1650s, Vermeer painted two small, intensely colored pictures: the Officer and Laughing Girl and The Milkmaid (fig. 5). While both are set in the left-hand corner of a room, they immediately stand apart from the somber A Maid Asleep and Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window for the cool, exceptionally vibrant light that bursts in through the window instilling life into all it meets, both figures and inanimate objects.

The theme of the Officer and Laughing Girl (fig. 6) is based on the popular Dutch guardroom motif in which military men are depicted engaged in gaming, drinking, rebel-rousing, or bothering young women. Perhaps Vermeer's composition is based on Gerrit van Honthorst's saucy bordello scene, The Procuress (fig. 7), but the Delft master has stripped his work of any sort of the motif's traditional low-life implications. Since the model is wearing a blue work apron over her dress (largely hidden in the shadow cast by the table) art historians have suggested that she had been surprised by an impromptu visit by the dashing military man during her morning chores. The window featured in the Officer and Laughing Girl is the same as the window in the Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window. While the map in the painting has been subject to various interpretations, it could also serve primarily as a compositional filler with an aesthetic rather than a symbolic function.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1655–1660

Oil on canvas, 50.5 x 46 cm.

Frick Collection, New York

Gerrit van Honthorst

1625

Oil on panel, 71 x 104 cm.

Centraal Museum, Utrecht

Camera Obscura

While no historical evidence confirms Vermeer's use of the camera obscura—a rudimentary photographic camera fitted with a lens but lacking film—the forced perspective, high contrast, and globular quality of reflections and highlights in his work have led most art historians to believe that he likely used this device as a painting aid. Although painters of the period were apparently aware of the camera, it has been closely associated mainly with Vermeer and Johannes van der Beeck (1589–1644) also known as Johannes Torrentius. Although Torrentius may have used the camera obscura as an aid to painting—only one such painting (fig. 8) has survived—contemporary documents suggest he may have desired to keep it secret.

The debate over Vermeer's use of the camera obscura extended from the early years of Vermeer studies until the early 2000s. It was Philip Steadman's publication, 'Vermeer's Camera,' that tipped the scales in favor of Vermeer having used the device.

Johannes van der Beeck

1614

Oil on panel, 52 x 50.5 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Steadman emphasized two principal uses to which Vermeer could have put his camera. "The first was as an aid to composition. The camera is a device…which collapses a scene into a flat picture onto a luminous screen. Vermeer would have set out his pieces of furniture and positioned his sitters in some provisional arrangement, chosen a viewpoint, set up his camera, and studied the resulting image on the camera's screen. He would have gone on to make adjustments to the positions of furniture and viewpoint, and alterations to the models' poses, always judging the consequences for his composition by reference to the optical image, until he was finally satisfied. He composed, that is to say, with the objects and human figures themselves—much like a studio photographer or a filmmaker. His second use of the camera would have been to trace detail and obtain accurate perspective outlines."Philip Steadman, "Vermeer's Camera: afterthoughts, and a reply to critics," http://www.vermeerscamera.co.uk/reply5.htm. Whether one believes that Vermeer employed the camera obscura methodically, occasionally, or never at all, the serious anomalies in anatomy, perspective, illumination, and proportion in Vermeer's first paintings disappeared as if by magic.

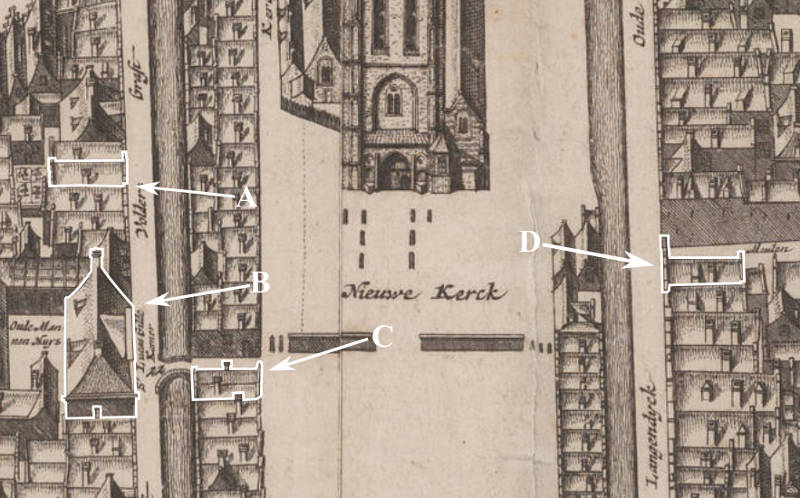

A. Flying Fox (Vermeer's presumed birthplace and inn of his father)

B. The Delft Guild of St. Luke (professional organization of artists and artisans)

C. Mechelen (a large tavern on the Market Square rented by his father where Vermeer and his family lived after the Flying Fox

D. Groot Serpent (studio & living quarters where Vermeer resided with his wife, children, and mother-in-law, Maria Thins?)

E. Trapmolen (studio & living quarters where Vermeer resided with his wife, children, and mother-in-law, Maria Thins?)

The Milkmaid, one of Vermeer's most powerful works executed when the artist was only in his mid-twenties, is kindred in both spirit and vigor to the Officer and Laughing Girl and must have been painted long before or after it. Despite the work's traditional title (milkmaids actually milk cows) the painting shows a kitchen maid in a plain room carefully pouring milk into an earthenware container (now commonly known as a "Dutch oven"). The stale bread, which lies in broken chunks on the vivid green tablecloth, is presumably, together with the milk that issues from the stoneware jug, an ingredient for making simple bread pudding. The picture's exceptional illusionistic impact, minute details and sympathetic treatment of the humble kitchen maid made the picture highly appraised in Vermeer's time and today. Never again did Vermeer portray a member of the lowly working class. Some critics have speculated that the woman who posed as the kitchen maid was a certain Tanneke Everpoel, probably employed as a maid in the Thins household. In 1663, years after The Milkmaid was painted, Tanneke would testify to a notary on behalf of Maria Thins.

Scenes of Haute Bourgeoisie Life

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1659–1660

Oil on canvas, 78 x 67 cm.

Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Brunswick

Immediately after the two breakthrough works mentioned above, Vermeer channeled his creative energies toward to a completely new and broader type of picture, such as the Girl Interrupted at Music, The Girl with a Wine Glass (fig. 9) and The Glass of Wine. All three of these complex scenes represent a moment of restrained courtship. In two of them, music-making is a subtheme. The figures and furniture that are placed in the middle ground of a deep, box-like space arrangement of windows and other elements create, as Walter Liedtke points out, a "self-sufficient" image.Walter Liedtke, ed., exh. cat. Vermeer and the Delft School (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001), 158.

In the Girl with a Wine Glass, the most carefully contrived on the three works, the artist employed various means to enhance the sense of spatial recession: overlap, one-point perspective, sharp, and blurred contours, and variations in color saturation—brighter colors which seem nearer to the viewer's eye are reserved for the foreground figures while the background figures are depicted with drab greens and browns. The small ochre and blue ceramic tiles of the Girl with a Wine Glass and The Glass of Wine betray problems in perspective, which were soon replaced by the wider and more "manageable" black and white marble floor tiles typical of the artist's subsequent interiors. The annotations of the chips and cracks of the ceramic tiles suggest that they were observed from life, perhaps in Vermeer's house, while the elegant marble tiles are almost certainly the fruit of artistic license. Due to their expense (marble had to be imported) and impracticality, marble floorings were rarely found in private homes, and then only in entranceways or corridors where they could be optimally appreciated by guests. Simple wood- planked floors were preferred by both the rich and humble for domestic use because they naturally insulated the Dutchmen's feet against the long gelid winter's cold. Unlike Pieter de Hooch (1629–1684), Vermeer always set the floor tiles obliquely to the background wall, presumably in order to temper the strong recessional effect of perpendicular tiles when created with one-point perspective.

Pieter de Hooch

c. 1657

67.9 x 58.4 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The left-hand corner of the room of these three interiors was certainly inspired by De Hooch's luminous interiors of Delft middle-class life such as The Visit (fig. 10) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This compositional model had already been experimented in other parts of Southern Holland but nowhere, except in the works of De Hooch, had space and the transient effects of daylight and naturalness of everyday gesture been married so happily.

The intense coloring and relatively uneven surface of the Glass of Wine connect it with the earlier Milkmaid and Officer and Laughing Girl while the Girl Interrupted in her Music and Girl with the Wine Glass are painted differently, with thin layers of paint. The gossamer surfaces and continuous modeling of the latter works recall the interiors of Ter Borch and Van Mieris rather than De Hooch's detailed but comparatively roughly painted Delft interiors. Importantly, the first signs of a strict geometrical order appear and will become a dominant concern until the end of the painter's short career. The tactile and sculptural qualities of Vermeer's early canvases are abandoned: form is no longer created via pictorial analogy or textural description but it is suggested with subtle shifts in tone and hue.

It is almost certain that Vermeer's early haute-bourgeoisie interiors do not reflect the artist's real living conditions—Vermeer's home was full of children, cribs, and an assertive mother-in-law—yet are artfully contrived mise-en-scène, and are intended to appeal to a restricted market of affluent and sophisticated clients. Historians have shown that middle-class Dutch homes were typically much darker and far more cluttered than are the pristine interiors of Vermeer.

The Little Street

Pieter de Hooch

Oil on canvas, 69.3 x 53.8 cm.

1656–1657

The Royal Collection Trust, London

It is likely that Vermeer painted The Little Street, and another lost street scene, some years before the last three interiors. It has been conjectured that it represents a view from the first story of the backside of Mechelen overlooking the canal on Voldersgracht. Many critics connect this work with the quietism of the Delft courtyard scenes (fig. 11) pioneered by De Hooch.

Unlike De Hooch, Vermeer, who would father 15 children in all before his death, never painted children except for the two figures playing quietly on the cobblestone sidewalk in the The Little Street.

Much has been written about Vermeer's models but nothing is really known about them. Most appear to be well behaved, cultured and in their mid twenties or early thirties. The heads of the four tronies are depicted so simply that the models could be either adolescents or young adults. No old women, men, or domestic animals are ever pictured (a dog originally stood back to the viewer looking through the open doorway of the A Maid Asleep but was painted out by the artist). All the figures in Vermeer's interiors hold poses that we would not expect to change quickly. It is principally through the figures' discreet gestures, rather than facial expressions, that we gain access, albeit limited, to their emotions and thoughts. Many writers claim that some of the women in Vermeer's pictures are in an advanced state of pregnancy while art historians are more cautious. Pregnant women were never portrayed in any type of Dutch painting, even in portraits of young married couples where pregnancy would appear to be statistically probable.

The relationship between De Hooch and Vermeer has been the source of considerable debate among art historians. It was initially assumed that De Hooch had exerted influence on Vermeer's work, but this verdict has been partially overturned, although it seems evident that the relationship was beneficial for both. Vermeer borrowed compositional motifs from the more inventive de Hooch, while Vermeer may have stimulated De Hooch to improve his draftsmanship, perspective, and application of paint. Certainly in a small town such as Delft, the two painters, who both belonged to the Guild of Saint Luke, could not have ignored each other's work.

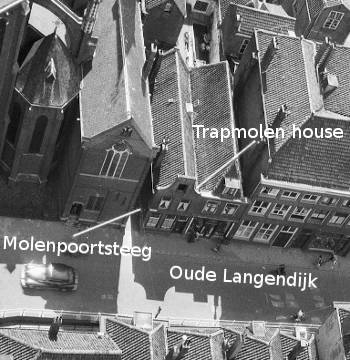

Little is known about Vermeer's civic or private life in these years. One of the few documents that refers to his life comes from the registry of the Oude Kerk in Delft and is dated December 27, 1660. It states laconically that a child of "Johannes Vermeer on the Oude Langendijk" was buried in a family tomb in the Oude Kerk (previously purchased by Maria Thins). At the time, Vermeer and his wife, who lived in his mother-in-law's spacious house, had three or four children, probably all girls.

It is not known exactly when Vermeer and his wife moved into Maria Thins' spacious house on Oude Langendijk, practically a stone's throw away on the other side of the Market Square; we know only that the burial record mentioned above confirms that he was living there by 1660. Some have suggested that Maria Thins would not have accepted the relatively poor and Protestant painter as a member of her patrician household, and that the young couple perhaps rented rooms somewhere before 1660.

G. Th. Delemarre

1962

Amersfoort, Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands

Historically, art historical literature has claimed that Vermeer and his family resided in the large Serpent house at the east corner of the Molenpoort and Oude Langendijk, owned by Maria Thins. However, recent in-depth archival research by Hans Slager indicates that Vermeer's family actually lived in the smaller Trapmolen house (fig. 12) on the west corner. The Serpent house, visually represented in the "Kaart Figuratief" mapThe Kaart Figuratief refers to a detailed, bird's-eye view map of the city of Delft in the Netherlands. Created between 1675 and 1678, it offers an illustrative representation of the city, capturing its layout, buildings, canals, streets, and other significant features. This map is particularly valuable for historians and researchers because it provides insight into the city's structure and appearance during the late 17th century. from the late 1670s, was an unusually large property with unique features, including a notable seven fireplaces. This significant number of fireplaces related to the former functions of the house as a malt house and inn. The Serpent house was later demolished in phases and replaced by the Maria van Jessekerk. The common belief that the Serpent house was Vermeer's residence stems from the assumption that it was owned by "Jan Tin," thought to be Jan Geensz Thins, Maria Thins's cousin. However, Slager's research revealed that this belief is flawed. It turns out the actual house Jan Geensz Thins purchased in 1641 was not the corner building but a different address nearby. Moreover, 1667 tax records show that Pieter van der Dussen, from a prominent Delft Catholic family, was the actual owner of the Serpent house, debunking the long-held belief about Vermeer's residence.

Christiaan Bos

publisher: J.J. Van Gessel, Delft, 1858.

Delft, Stadsarchief, inv. no. 65770

The first detailed depiction of the Trapmolen buildingThe house may have been extensively renovated quite recently, but the layout of the house appears to be largely the same as in Vermeer's time. There is still an 'indoor kitchen' on the ground floor with a chimney (rug), bellows, ash racks and a box bed. Here also a Frisian clock and lots of kitchen crockery. There is also a cellar, which the current owner told Slager that his predecessor had to close due to moisture problems. A number of 17th century Delft blue tiles were rescued from the cellar in advance and used as decoration elsewhere in the house. In 1801 we found wine racks, an egg rack and a remarkable amount of table cutlery in the cellar. There are also a few spittoons for spitting chewing tobacco. The upstairs front room, where Vermeer's studio was located in 1675, now contains a 'drop-leaf table' (with a fold-out table top), five chairs, a bedstead and a wardrobe. From: "Oude Langendijk 25," Achter de gevels van Delft, Kees van der Wiel, with contributions from Hans Slager and Wim Weve. is from an 1858 image by Leiden lithographer Christiaan Bos. (fig. 13) The illustration highlights notable architectural features, such as two chimneys, windows, a billboard on the Molenpoortsteeg, and the front door's central position, a common placement in seventeenth-century architectural design. Historical records dating back to1600 provide additional insights into the building's characteristics.

However, notwithstanding eventual initial reservations, Vermeer must have proven his trustworthiness via his conversion to Catholicism, a choice not without consequences, immediately before or after his marriage to Maria's daughter. "Furthermore, until she had her abusive son Willem confined to a house of correction in the 1660s (at a cost of 310 guilders a year) Maria Thins was remarkably tolerant of her son's hostile behavior. This suggests that she would not have punished her only other surviving child, Catharina, by keeping her and her new husband out of the large house on the Oude Langendijk. On the contrary, Maria Thins must have been cautiously supportive of the decent young man, about whom not a single negative remark is recorded apart from debts."Walter Liedtke, ed., exh. cat. Vermeer and the Delft School (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001), 149.

There is no indication that Vermeer ever traveled farther from Delft than Amsterdam. The idea that he had traveled to Italy has been proven unfounded.

The Pearl Pictures

In the early- and mid-1660s Vermeer executed five small canvases eloquently named the "pearl pictures," as named by Lawrence Gowing, which are among the artist's most lucidly conceived yet enigmatic works: Young Woman with a Water Pitcher, Woman in Blue Reading a Letter (fig. 14), Woman Holding a Balance, Woman with a Lute and Woman with a Pearl Necklace. These works are, remarkably enough, more noteworthy for their naturalistic qualities than his works of the late 1650s, in large part because even their most striking passages are subordinated to the impression made by the whole.Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., "Any literal description of such deceptively simple works can in no way prepare the viewer for the singularity these images," in exh. cat. Johannes Vermeer, eds. Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Ben Broos (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 134.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 46.5 x 39 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The subject matter of the pearl pictures is restricted to a single woman who momentarily engages in some discreet activity in a left-hand corner of a room, very near a window, sometimes in view,sometimes not. While persistent iconographical interpretations seem to have successfully illuminated the story behind the Woman with a Balance, the other works have largely resisted interpretative attempts. Nonetheless, a common theme that unites the women's activities might be that of thoughtful reflection.

Even by Vermeer's standards, the scenes of the pearl pictures are organized with exceptional economy utilizing as props only a table, a meager still life, a map or painting on the background wall and one or two chairs (infrared reflectograms reveal that the original version of Woman with a Pearl Necklace once displayed a large wall map behind the standing girl, later painted out). All the scenes are staged against a simple, whitewashed wall set parallel to the picture plane. The particular chromatic and tonal values of the walls are key to establishing the direction, intensity, and temperature of the incoming light. Despite their deceptively unproblematic appearance, Vermeer's walls constitute an unsung technical tour de force.

Two paintings of the same size in The National Gallery,A Lady Standing at a Virginal and A Lady Seated at a Virginal. London, are believed by some, including Walter Liedtke, to have been created by Vermeer as pendants—pieces that complement each other but can also stand alone. While some scholars doubt they were made as a pair and suggest different creation dates for each, Brown places both around 1670 but questions their relationship as pendants. Wheelock contends that they were created at different times between 1672-1675 and argues against them being a pair. Liedtke, on the other hand, argues that the paintings are complementary in their themes, and any stylistic differences are intentional to highlight the contrasting characters of the women portrayed. This viewpoint has gained acceptance and even led to one of the paintings being reframed in 2001 to match the other.Walter Liedtke, The Complete Works (London: Abrams, 2008), 170.

Violence

A sense of unspeakable serenity and balance reign over each of the pearl pictures. This achievement is all the more significant when we remember that in those years the artist's family life was filled with trauma. A glimpse of the hardship is revealed by a succinct notarial deposition made in 1663 by Gerrit Cornelisz., stone carver, and Tanneke Everpoel. Tanneke stated the following,

"That on various occasions Willem Bolnes [Maria Thins's jobless and irascible son] had created a violent commotion in the house—to such an extent that many people gathered before the door—as he swore at his mother, calling her an old popish swine, a she-devil, and other such ugly swear words that, for the sake of decency, must be passed over. She, Tanneke, also saw that Bolnes had pulled a knife and tried to wound his mother with it. She declared further that Maria Thins had suffered so much violence from her son that she dared not go out of her room and was forced to have her food and drink brought there. Also that Bolnes committed similar violence from time to time against the daughter of Maria's, the wife of Johannes Vermeer, threatening to beat her on diverse occasions with a stick, notwithstanding the fact that she was pregnant to the last degree."John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 161.

Tanneke added that she was able to prevent some of the violence herself. Another witness, Willem de Coorde, declared that on various occasions he had stopped Bolnes from entering the house and "several times thrust at his sister with a stick at the end of which there was an iron pin." As early as 1653 Willem was already making trouble calling on Maria Thins to lend him money. Maria's sister, Cornelia, had disinherited Willem in a last testament made shortly before she died in1641. After years of hesitation, Maria Thins had her son committed to a house of correction, and at least a semblance of domestic peace returned to the Vermeer household. Willem later escaped the house of correction with a maid with whom he had become sexually involved promising to marry her when he was free. Willem was later caught and he seems to have repented. No evidence has survived regarding how the painter had reacted to the spiraling violence; this seemingly apparent incoherency should warn us that the personal affairs of an artist may be very remote from the art he produces.

The Music Lesson and The Concert

Sometime in the 1660s, perhaps after the three box-like interiors and before the pearl pictures, Vermeer painted two of his most ambitious interiors, The Music Lesson (fig. 15) and The Concert (fig. 16). A number of Delft interior and church paintings dating from the early 1660s feature forced perspectives although the trend was not only limited to Delft but extended to Rotterdam, Dordrecht, and Antwerp. Both pictures have posed many interpretative problems to art historians, and some consider them a pendant, although the paint handing is different enough to suggest they were painted years apart; the compositional failings of The Concert are evident when it is compared side by side to its "companion," one of the artist's most original artistic statements.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 73.3 x 64.5 cm.

The Royal Collection, The Windsor Castle

c. 1663–1666

Oil on canvas

72.5 x 64.7 cm.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

A sequence of objects on the right-hand half of The Music Lesson lead the viewer from the foreground table into the cavernous depth of space, each one overlapping the other. The inscription on the lid of the virginal, MUSICA LETITIAE CO[ME]S / MEDICINA DOLOR[IS], means "Music is a companion in pleasure and a balm in sorrow." It suggests that it is the relationship between the man and the young woman that is being explored by the artist, but the current stage of that relationship is unclear. A painting of Roman Charity in the ebony frame to the extreme right of the composition, in which the Cimon is pictured bound in chains, may allude to the gentleman captivated by the smartly dressed virginal player. The Roman Charity was likely the work described as "A painting of one who sucks the breast" cited in the list of Maria Thins' belongings.

In 1662, on Saint Luke's Day, Guild members, from various crafts, convened to elect their officials for the upcoming year. Six nominees, representing different crafts, were proposed, from which the town's leaders selected three headmen. Vermeer was among those elected. At around the ager of thirty, Vermeer became one of the youngest to assume this position since the Guild's reformation in 1613. This election underscored the esteem he held among his peers, although many talented painters from the previous decade had either passed away or left town, leaving behind mostly mediocre talents. While Vermeer's youth made his appointment notable, the diminished competition made it less surprising. His Catholic faith did not hinder him, as other Catholic painters had held office in the past.John Michael Montias."Chronicle of a Delft Family." in Vermeer, edited by Albert Blankert, Gilles Aillaud, and John Michael Montias, (Woodstock and New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2007), 51.

On November 12, 1663, Vermeer was listed as an outgoing (second-year) headman of the Guild of Saint Luke in Delft. The incoming headman was Anthonie Palamedesz (1601–1673), a successful painter of interiors in Delft. In an inventory drawn up for the English sculptor who lived in The Hague, "a head by Vermeer" by Jean Larson was listed "a head by Vermeer."