publisher: Fokke, Simon

printmaker & designer: Hermanus Petrus Schouten

Etching on paper, 35.7 x 28.8 cm.

1774

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

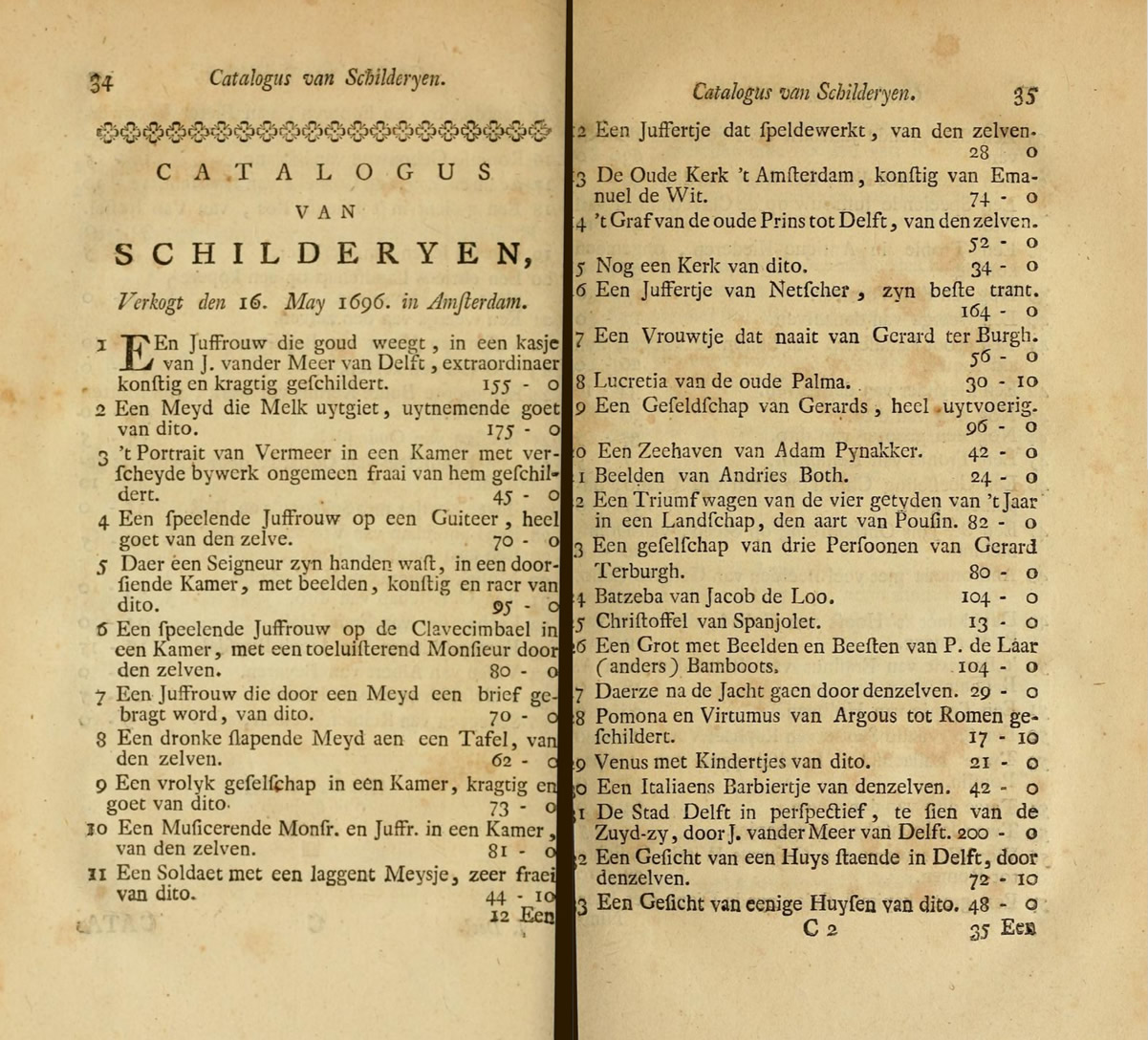

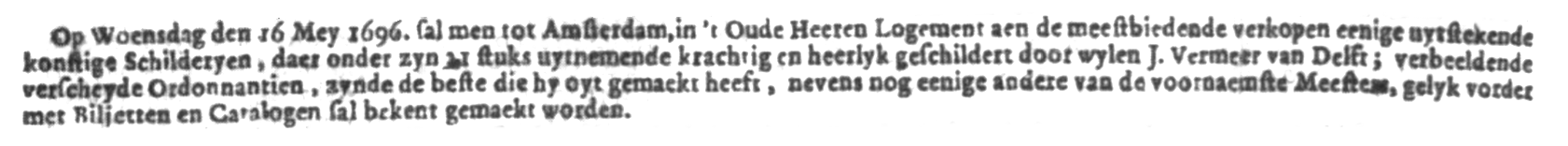

On 16 May 1696, 134 paintings from unnamed sources were auctioned at the Oude Heeren Logement (Old Men's Lodging House) (fig. 1, 2 & 3) in Amsterdam, perhaps in the building's courtyard where auctions were usually held. Included were listed twenty-one paintings by Vermeers that brought a total of 1,503 guilders and 10 stuivers, then a substantial sum, enough to buy a comfortable house. The auction lists more than ninety other paintings, some of which fetched higher prices than Vermeer's works, although we do not know whether all the paintings in the catalog came from Dissius. Included were three church interiors by Emanuel de Witte).

Save for the Rijksmuseum 2023 Vermeer retrospective with 28 (?) works, it was the biggest assembly of Vermeer paintings ever to have been brought together under one roof. Several weeks earlier, the Amsterdamsche Courant printed an announcement (fig. 1) that there would be sold "several outstandingly artful paintings, including 21 works most powerfully and splendidly painted by the late Vermeer of Delft; showing various Compositions, being the best he has ever made."

After the sale, most of the paintings disappeared from view for many decades, some for more than two centuries. Vermeer's name, too, quickly fell into oblivion; the fact that his oeuvre was small also made it easier for his name to be forgotten. Before the recovery of Vermeer's art, which was initiated in the mid-1800s by the French journalist and art critic Thoré-Bürger (1807–1869), a few paintings were given different signatures to increase their commercial value. Some turned up well into the 19th century. Three works listed in the catalogue have vanished since completely: no. 3 and 32 or 33).

Pierre Fouquet Jr.

1872

Hand colored print

British Museum, London

Today, the twenty-one works listed of the Amsterdam auction would be considered one of the premier art collections of the Western world, surpassed only by the Louvre, the London National Gallery and the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

It was long believed it was the Delft Jacob Dissius (1653-1695) who had amassed such an imposing collection, and yet, on 14 April 1680 he had been described as a "bookbinder with no means of his own."

Until recently authors still wrote: "Vermeer's most important customer was Jacob Dissius."The original list of Dissius' Vermeers had been discovered by, Thoré-Burger, who reprinted this list in his catalogue raisonné. He assumed it represented works left on Vermeer's hands at the then unknown time of his death. Following the research of Abraham Bredius,Bredius, Abraham. "Iets over Johannes Vermeer." Oud-Holland III (1885): 222. it had long been assumed that this collection is identical with that outlined far more summarily in the inventory drawn up early in 1683 of the estate and property of Dissius.

However, in 1989, the American economist John Michael Montias published his seminal Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History which showed that Dissius had not acquired the paintings himself but had inherited them via his marriage to the Delft burger Pieter van Ruijven's daughter Magdalena. In fact, the Delft archives reveal that Dissius was only twenty-two years old when Vermeer passed on. He, therefore, could hardly have been one of Vermeer's patrons.

Following Montias's discovery, with the exception of Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., specialists overwhelmingly concord that it was the well-to-do Delft burger and art-lovers Van Ruijven (1624–1674), and his wife, Maria de Knuijt (d. 1680), who had acquired the paintings, most likely directly from the painter, thereby steadfastly sustaining the artist's activity, a rare commitment in seventeenth-century Netherlands. Thus, the couple merits the honor of being remembered as the only patrons of Vermeer worthy of that title. The works they had collected presumably span from c. 1657 to c. 1673; from the time he began to paint genre scenes, cityscapes and his last highly-stylized works. None of the artist's surviving mythological or religious paintings seem to have been acquired by the Van Ruijvens.

The story is such.

"Pieter van Ruijven died in August of 1674 [one year earlier than Vermeer], just forty-nine years old, followed by Maria de Knuijt in February of 1681. In early April 1680, their only daughter, the twenty-four-year-old Magdalena, married Jacob Dissius, the son of the owners of the Vergulde ABC (The Golden ABC) printing house (fig. 4) located on the Markt. Their marriage, however, was short-lived: the young wife died just two years later, in June 1682, presumably in childbirth. Along with 39 other pictures, a Delft notary recorded no fewer than twenty paintings by Vermeer—and a few musical instruments, in the estate inventory that her husband had drawn up in their house on the Markt, April 1683. Magdalena had most likely inherited most of these works from her mother Maria two years earlier. The list reveals how the young couple lived among Vermeer’s paintings. Hanging in the front room were ‘acht schilderijen van Vermeer’ (eight paintings by Vermeer) and ‘drie dito van dezelfde in kastjes’ (three ditto by the same in boxes), another four in the back room, one in the kitchen, two in the cellar and two more elsewhere in the house, one fewer than the number auctioned in the 1696 sale. Dissius, too, died young, in October 1695, just shy of his forty-second birthday. As many as six of the nine paintings from the years 1657−1661 appear in the sales catalogue. Could the change of genre within Vermeer’s oeuvre in these years have been directly encouraged by Pieter van Ruijven and Maria de Knuijt? The overall list of paintings in the auction bolsters the suspicion that they bought Vermeer’s works over a longer period, most of them directly from the painter, and other pieces perhaps by De Knuijt after the death of both Van Ruijven and Vermeer from the latter’s estate."Roelofs, Pieter. In Vermeer, edited by Pieter Roelofs and Gregor Weber, 223-223. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2023l. Initially, and for reasons that are not clear, Van Ruijven's estate was divided between Dissius and his father Abraham. Among Abraham's share were fourteen paintings, including six by Vermeer. His son Jacob inherited these along with the rest of his father's estate when Abraham died in 1694.

In any case, critics and archivists have remarked the difference between the 21 paintings by Vermeer in the 1696 Amsterdam auction and the 20 cited in the auction after Jacob's death in 1695. At some point, one other Vermeer painting must have been added. The difference has been explained variously, including that one work by Vermeer had been identified erroneously as by another artist. Montias suggested that the twenty-first Vermeer was also listed in the 1683 Dissius inventory, where the notary must have failed to write "by Vermeer" after one item.

Two buyers at the Amsterdam auction are now known: a rich small arms manufactor Jacob Oortman (1696-1748) and the Mennonite merchant Isaac Rooleeuw (1650-1710 ), who managed to acquire two excellent works.

"A well documented case can now be added to our scarce knowledge on the position of Vermeer in early 18th-century collections. We knew already that Mistress and servant (Frick Collection, New York) was sold at an anonymous auction in 1738 to someone called Oortman. As it appears, this was Hendrik Oortman (1696-1748), who bought the picture by Vermeer in 1738 on the auction of the paintings that belonged to his father, Jacob Oortman (1661-1738), pistol and gun maker and one of the wealthiest men in Amsterdam at the time. Jacob possessed some 80 paintings, a dozen of which were probably bought at the Dissius auction of 1696, along with the Vermeer. They were kept in his house on Singel, Amsterdam. Thanks to the inventory of Jacob Oortman’s belongings made up after his death, we are able to document the disposition of these paintings in the house fairly well. Apart from a nice collection of porcelain, Oortman owned a couple of interesting pictures, among which Pieter de Hooch’s famous Mother’s Duty, now in the Rijksmuseum."Grijzenhout, Frans. "A writer by Vermeer. Jacob Oortman and the Dissius auction of 1696." Oud Holland 123 (2010): 65-74.

As for Rooleeuw, the first lot of the auction was hammered down to him for 155 guilders: ''A Damsel who weighs gold ... painted with extraordinary art and power." He also became the lucky owner of number two in the catalogue: ''A Maid who pours Milk, outstandingly good." Rooleeuw was even prepared to pay 175 guilders for it. He then let other paintings by Vermeer pass by, even though they were described as: " uncommonly handsome,"very good,"artful and rare,"powerful and good" and "very handsome." The most important painting, the View of Delft, went for 200 guilders to a yet unidentified art lover. In any case, Rooleeuw did not enjoy his two Vermeers for long: in 1701 he went bankrupt. After the assessor Jan Zamer had completed the inventory of the collection, the paintings were bound together in pairs and sealed with the Amsterdam city seal before being sold to the highest bidder.

After the auction, Vermeer's paintings were held privately for many years, sometimes centuries. When some resurfaced, they were incorrectly attributed to other Dutch artists, such as Pieter de Hooch and Rembrandt whose authorship at the time would have increased their monetary value.

The only informed Vermeer specialist who is remains suspect of the of the patronage of Van Ruijvens remains Arthur K. Wheelock Jr.

"The hypothesis that Van Ruijven was Vermeer's patron, although appealing, should be cautiously approached, for no document specifies that Vermeer ever painted for Van Ruijven. Moreover, no source confirms that Van Ruijven himself had any Vermeer paintings in his possession. In the agreement for the loan that he made to Vermeer in 1657, which Montias interprets as 'an advance toward the purchase of one or more paintings,' no such arrangement is stipulated. On the contrary, Vermeer and Catharina Bolnes [Vermeer's wife] promised to return the sum within a year ... together with interest ... until full repayment shall have been effected. Should they fail to meet their obligation, the couple declared themselves 'willing to ... be condemned by the judges of this city.' The agreement never mentioned paintings as an alternative form of payment.

While Van Ruijven may have acquired paintings from Vermeer, it seems unlikely that he assumed as important a role in the artist's life as Montias suggests. Should Van Ruijven have been Vermeer's patron, one would expect that the traveling Frenchman Balthasar de Monconys would have visited Van Ruijven in 1663 rather than a baker, presumably Hendrick van Buyten, upon hearing that Vermeer had no paintings at home. Similarly, the Vermeer enthusiast Pieter Teding van Berckhout would also have made an effort to see Van Ruijven's collection in 1669 on his two visits to Delft." Wheelock Jr., Arthur K. In Johannes Vermeer, edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Ben Broos, 22-23. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1995..

To art historians, the Amsterdam auction's chief importance lies in the catalogue descriptions of the 21 paintings which comprises one of the few solid historical foundations scholars have for determining which are genuine Vermeer paintings and which are not. Some of the auction descriptions are too vague to be of much use. But about 15 or 16 of those 21 listed have been identified today with reasonable certainty.

This list of the Dissius auction was garnered from the massive "Catalogus of Naamlyst van Schilderyen, met derselver Pryze" (Catalogue or List of Paintings with Their Prices) published by Gerard Hoet II (1698-1760), a multi-volume work published between 1752 and 1780 that provides lists of artworks sold at auctions, their prices and often the names of the buyers. Elisabeth Neurdenburg was the first to show that the paintings in the Hoet II catalogue could be traced to the art collection of DissiusNeurdenburg, Elizabeth. "Johannes Vermeer. Eenige opmerkingen naar aanleiding van de nieuwste studies over den Delftschen Schilder." Oud Holland 59, no. 3 (1942).

Click on the auction catalogue number or the Dutch title to view information about an eventual comparison with one or more of Vermeer's surviving work (paintings not by Vermeer's hand are not linked).

| NO. | TITLE | PRICE (guilders-stuivers) |

| 1. | Een Juffrouw di goud weegt, in een kasje J. vander Meer van Delft, extraordinaer Konstig en kratig geschildert. (A young lady weighing gold, in a box, by J. van der Meer of Delft, extraordinarily artful and vigorously painted.) |

155-0 |

| 2. | Een Meyd di Melk uytgiet, uytnemende goet van dito.

(A maid pouring out milk, extremely well done, by ditto.) |

175-0 |

| 3. | Portrait van Vermeer in een kamer met verscheyde bywerk ongemeen fraai van hem geschildert. (The portrait of Vermeer in a room with various accessories, uncommonly beautiful painted by him.) |

45-0 |

| 4. | Een speelende Juffrow op een Guiteer, heel goet van den zelve. (A young lady playing a guitar, very good by the same.) |

70-0 |

| 5. | Daer een Seigneur zyn handen wast, in een doorsiende Kamer, met beelden, konstig en raer van dito. (In which a gentleman is washing his hands in a perspectival room with figures, artful and rare, by ditto.) |

95-0 |

| 6. | Een speelende Juffrouw of the Clevicimbael in een Kamer, met een toeluisterend Monsieur door den zelven. (A young lady playing the clavicen in a room, with a listening gentleman, by the same.) | 80-0 |

| 7. | Een Juffrouw die door een Meyd een brief gebragt word, van dito. (A young lady who is being brought a letter by a maid, by ditto.) |

70-0 |

| 8. | Een dronke slapende Meyd aen een Tafel, van den zelven. (A drunken sleeping maid at a table, by the same.) |

62-0 |

| 9. | Een vrolyk geselschap in een Kamer, kragtig en goet van dito. (A gay company in a room, vigorous and good, by ditto.) |

73-0 |

| 10. | Een Musiceerende Monsr. en Juffr. in een Kamer, van den zlven. (A gentleman and a young lady making music in a room, by the same.) | 81-0 |

| 11. | Een Soldaet met een laggent Meysje, zeer fraie van dito. (A soldier with a laughing girl, very beautiful, by ditto.) |

44-10 |

| 12. | Een juffertje dat speldewerkt, van dem zelven. (A young lady doing needlework, by the same.) |

28-0 |

| 31. | De Stad. Delft in perspectief, te sien van Zuyd-zy, door J. vander Meer van Delft. (The Town of Delft in perspective, to be seen from the south, by J. van der Meer of Delft.) |

200-0 |

| 32. | Een Geschit van een Huys staende in Delft, door denzelven. (A view of a house standing in Delft, by the same.) |

72-10 |

| 33. | Een Geschit van eenige Huysen van dito. (A view of some house, by ditto.) |

48-0 |

| number 34. was skipped in the Hoet catalogue | ||

| 35. | Een Schyuvende Juffrouw heel goet van denzelven. (A writing young lady, very good, by the same.) |

63-0 |

| 36. | Een Paleerende dito, seer fraye van dito. (A lady adorning herself, very beautiful, by ditto.) |

30-0 |

| 37. | Een Speelende Juffrouw op de Clavecimbaerl van dito. (A lady playing the clavicen, by ditto.) |

42-10 |

| 38. | Een Tronie in Antique Kelderen, ongemeen konstig. (A tronie in antique dress, uncommonly artful, by the same.) |

36-0 |

| 39. | Nog een dito van Vermeer. (Another ditto by Vermeer.) |

17-0 |

| 40. | Een weerge van denzelven. (A pendant by the same.) |

17-0 |