In Vermeer's The Little Street (fig. 1), one of the most evocative details is the pair of children, engrossed in their play. Though they are but a small part of the canvas, their presence infuses the scene with an added warmth that is indispensable to the painting's ambience. True to Vermeer's enigmatic signature style, he shields both their faces and the specifics of their game from view.

From the attire, one could speculate that the child donned in darker hues with a broad-brimmed hat is a boy, while the other, in distinctly feminine dress, is a girl. By having them turn away from us and obscure their activity, Vermeer invites the audience to delve into their own recollections of youth. This masterstroke ensures that viewers arenvt just passive observers, but also co-creators, breathing life into the quiet narrative of the artwork.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1657–1661

Oil on canvas, 54.3 x 44 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The poignancy of this painting becomes even more evident if we remember that Vermeer had eleven children: Maria, Elisabeth, Cornelia, Aleydis, Beatrix, Johannes, Gertruy, Franciscus, Catharina, Ignatius and one child whose name is unknown (see Vermeervs family tree for biographical notes). Four had died in infancy or early childhood. One was buried on 27 December, 1660 and three others were also buried in the Oude Kerk in a grave bought by their grandmother Maria Thins in December 1661, on 10 July, 1667 and on 27 June, 1673.

All of Vermeervs children were likely baptized in a Jesuit church, and their names were largely influenced by Catharina's Catholic family, particularly her mother Maria Thins, and various Catholic saints. For example, their firstborn daughter was named Maria, likely in honor of Maria Thins and the Virgin Mary.

The pattern of naming and the fact that their children were raised in the Catholic faith suggests, according to Gregor Weber,Gregor J.M. Weber, Johannes Vermeer: Faith, Light and Reflection (Rotterdam: nai010 Publishers, 2023), 31. that Vermeer did not just marry into a Catholic family but likely converted to Catholicism himselfIn seventeenth-century Netherlands, mixed marriages might be frowned upon or lead to a certain level of ostracization. However, the extent of this would largely depend on the specific community and how strictly they adhered to religious doctrines. In terms of civic rights, a Catholic woman marrying a Protestant man would not typically lose her civic rights outright, but she might face social scrutiny or discrimination. However, the couple could face obstacles if they wanted to hold certain positions within the established Dutch Reformed Church or community institutions that required a "pure" Protestant background.. This is supported by the naming choices, the children's Catholic upbringing, and the fact that their grandchildren were also baptized in the Jesuit church, with one even becoming a Catholic priest. The archival material strongly implies that Vermeer was not just superficially connected to Catharinavs Catholic faith, but that he and his wife raised their family deeply rooted in Catholicism.

While the era's high child mortality rates meant that many families experienced such loss—with nearly half of all children not reaching adulthood—the pain for each family was deeply personal.Several factors contributed to this high mortality rate. Epidemics such as smallpox, diphtheria, and measles could quickly wipe out large numbers of children in a short amount of time. There were no vaccines, and medical knowledge was limited. Sanitation in urban areas was not as advanced as it is today. Contaminated water sources and lack of proper waste disposal meant that diseases could spread easily. While the Dutch were advanced in many areas during the Golden Age, understanding of nutrition, hygiene, and medicine was still in its infancy. This lack of knowledge contributed to higher mortality rates. While the Dutch Golden Age was prosperous for many, there were still pockets of poverty. Children in poorer households had higher mortality rates due to malnutrition, lack of medical care, and other factors. Particularly among the Dutch, who were reputed to have a singular attachment to their children compared to the rest of Europe. This deep familial bond is further attested to by the plethora of Dutch paintings depicting children compared to those of the rest of Europe, a fact testified by a countless number of paintings that show children in all attitudes and activities (fig. 2 & 3).

Click here to access Vermeervs interactive family tree

"At the rate of almost one birth a year, the Vermeers had five or six children by 1661, three of four of whom survived. The first children who apparently lived into adulthood were all girls: Maria, Elisabeth, Cornelia, Aleydis, and Beatrix. With an eventual eleven living children, Vermeer may well have pondered how to divide his energies; his slow production of paintings meant he completed only some three pictures for every child. The poet Yeats later put the dilemma as which to choose, perfection of the life or of the work? A ruthless genius may opt for the latter. A more difficult task faces the home-loving artist who tries for both.

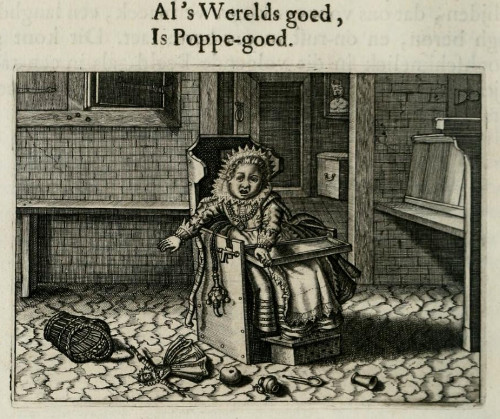

Sinnepoppen

Houghton Library

Harvard University

"We havenvt much to go on regarding daily details. We assume the children were got safely to and from school, taken to Mass on Sundays and holy days, made to say their prayers at night, and taken to city events such as fairs. They will have played the childhood games shown on Delft tiles of the time. In the winter of 1660 Vermeer apparently bought an ice-boat for the large sum of eighty guilders. Michael Montias has found a record of a debt for that amount owed by vJohan van der Meerv for such a craft in the estate accounts of a sailmaker, Daniel Gilliszoon de Bergh; that it was owed by our Vermeer seems probable given that those who witnessed the accounts were both painters, De Berghvs sons, Gillis and Mattheus."Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2002), 103–104.

"From what we know of their later lives, none of them seem to have inherited Vermeer's artistic skills or pursued distinguished careers. Vermeer's wife, Catharina Bolnes, who must have been pregnant for much of the time, also had the burden of looking after her mother. Although Maria (Catharina's mother) lived to be eighty-seven, surviving Vermeer, she was already nearly seventy when the family moved in and was presumably getting frail. Caring for eleven children, an aging mother, and an artist must have taken most of Catharina's time, even with the help of a maid. After Vermeer's death, she claimed to have known little about his business affairs since she had never concerned herself further or otherwise than with her housekeeping and her children. Martin Bailey,. Vermeer. (London: Phaidon Press, 1995), 207–208.

"The Vermeers's sixth surviving child and first son, also called Johannes, was having his education paid for out of income from farmland in Schoonhoven that had been Willem Bolnes's . The boy may have been sent to a Catholic college in Mechelen in the southern Netherlands; in which case, it may have been Johannes who was the child of Vermeer's who in 1678 was mentioned as being 'piteously wounded's in an explosion on a vessel carrying gunpowder from Mechelen. But young Johannes, if he was the wounded person, survived that minor ontploffing. He seems to have become a lawyer in Bruges, preserving his links with the Catholic south, and had a son, another Johannes, who preserved the artist's name but was brought up in Delft by his aunt Maria and her husband Johannes Cramer—despite which the boy doesn't appear to have learned to write (he put a cross rather than a signature on a power of attorney in 1713). He married a Delft girl but moved to Leiden where their five children—Vermeer's great-grandchildren—were baptized as Catholics. Another son of Vermeer, Franciscus, became a master surgeon in Charlois, a village near Rotterdam, and later moved to The Hague. Apart from Maria, Beatrix was the only one of Vermeer's daughters to marry. Aleydis, the fourth girl, lived until 1749 when she died in The Hague. Continuing remittances from their grandmother Thins's estates and from the Gouda Orphan Chamber apparently helped the unmarried daughters (including Aleydis, Gertruy, and Catharina, named after her mother) to subsist. Of the girls, Maria seems to have been the most fortunate through her marriage to Cramer; the couple had a number of children who were well provided for, and one of whom became a Catholic priest."Bailey, Vermeer. (London: Phaidon Press, 1995), 9.

In June 1674, one year before her father's death, Maria, about twenty years old, married the son of a prosperous Delft silk merchant named Gilliszoon Cramer. The wedding ceremony was held in Schipluy, where Maria's parents had been married, likely with Catholic sacraments.

Johan de Brune (1588–1658)

Publisher: T'Amsterdam

Vermeer's family was unusually large. "In the Dutch Republic of the seventeenth century, the family was the keystone of society and had many unique and advanced characteristics. The family unit was small and insular in orientation: the average of three or four children, and close relatives, such as grandparents, rarely shared the home. Children were treated by their parents with a respect and understanding unusual for the times, and received their moral instruction in the home, where they generally lived until their mid to late twenties." Montias, John M., and John Laughman. Private and Public Spaces: Works of Art in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Houses. (Zwolle: Waanders Books, 2000), 13. John Michael Montias, who has written the most exhaustive study of Vermeer's family, has noted the "chance factors affecting child-bearing activities, or the lack of it, of different members of the family played a major role in determining the same family's fortunes. The fact that Reynier Jansz. Vos alias 'Vermeer's (Vermeer's father) had only two children helped the family's ascent, just as the numerous progeny of the artist contributed to the family's downfall. The financial collapse would have been even more precipitous were it not for the penchant of Maria Thin's (Vermeer's mother-in-law) family for celibacy: her aunt Diewertje died a spinster, not one of Maria's four brothers and sisters ever married; her son Willem was briefly betrothed but remained a bachelor. On Vermeer's side, even his sister Gertruy had only one child, who apparently died in infancy. Johannes and Catharina and their numerous children profited from the failure of all these related to leave viable heirs. Unfortunately, these multiple windfalls could only palliate the disastrous effect of Catharina's unbridled fertility." John M. Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 245.

Children in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Paintings

During the seventeenth century, Dutch painters vividly captured the essence of their times, with depictions of children playing a singular role. These artworks shed light on various facets of life during this era.

Foremost, depictions of children in paintings often focused on scenes of daily life, or "genre." Children were portrayed engaging in playful activities (fig. 4), domestic chores or interacting with adults, providing a window into the customs and lifestyles of the period. But not all depictions of children were rosy. Some pictures, reflecting the broader societal realities, portrayed children engaged in hard labor, underscoring that leisure was a luxury not all could afford.

Beyond just pictorial representations, many of these works were meant to convey moral and didactic messages. Whether it was a depiction of a child's mischief or an illustration of virtuous pursuits, such images were more than just visual treats; they were lessons in paint and canvas. Interestingly, while the Italian Renaissance artists often portrayed children, especially the Christ child, in a stylized manner, Dutch and Flemish artists opted for more realistic and personalized renditions in attempts to capture their infinite moods.

The affluence of Dutch seventeenth-century society is evident in the numerous portraits commissioned by wealthy families. These portraits, while showcasing the opulence of the period through attire and accessories, also had a somber side. Given the high child mortality rates in the period, portraits of deceased infants occasionally served as mementos(fig. 5).

Religious themes also found their way into these paintings of children. They were less prominent in the Protestant Northern Netherlands compared to the predominantly Catholic south, where children often appeared in biblical narratives—from the innocence of the Christ child to the tales of young saints.

Judith Leyster

c. 1630

Oil on panel, 25.81 x 21.7 cm.

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester NH

Bartholomeus van der Helst

c. 1645

Oil on canvas, 63 x 86.5 cm.

Museum Gouda, Gouda

Where are Vermeer's Children?

It is difficult to imagine that the father of eleven children was not in some way or another influenced by their presence. Many critics have noticed the apparent discrepancy between Vermeer's perfectly ordered interiors and what may have been the artist's daily life with a brood of children. Where are the cradles, beds, and chairs that, according to the inventory of movable goods taken after his death, were strewn about the house? Contrary to many Dutch genre painters such as Jan Steen, Nicolaes Maes and Gabriel Metsu, who frequently represented children, Vermeer assigned them only two minor roles.

The issue is not as complex as it might appear. Simply put, Vermeer's paintings were not intended biographical statements. Even though they do represent contemporary settings and modes, they were not meant to reflect the conditions of his personal life. Vermeer worked within a well-defined genre where the painter created a subtle mix of convention and invention.

Montias notes that although the absence of domestic turmoil may seem conspicuous, the artist's "subjects and the way he handled them are rooted in much earlier experience and were invariant to the things that happened to him in his adult years."

Curiously enough, Vermeer directly portrayed children only two times in thirty-five paintings, once in The Little Street (fig. 1) and a second time in The View of Delft (fig. 6) where a young girl can be seen with an infant in her arms to the extreme left of the foreground. There are, however, more than a few indirect representations of children in other paintings. A painting-within-a-painting of Cupid appears either partially or entirely in three other works and at close inspection, we can see that children are represented, although highly abstracted, on the tile baseboards in The Milkmaid, A Lady Standing at a Virginal (fig.7) and A Lady Seated at a Virginal.

c. 1660–1663

Oil on canvas, 98.5 x 117.5 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

c. 1670–1674

Oil on canvas, 51.7 x 45.2 cm.

National Gallery, London

These hand-painted tiles were common in Dutch homes and had a wide export market (fig. 10). They protected the lower part of the white-washed walls from wet mops. However, while Vermeer's tiny depictions of the children might convey some of the childrenvs naive simplicity, they were likely incorporated to comment on the main theme of the artwork. In the case of A Lady Standing at a Virginal, the little Cupid on the tile directly to the left of the lower portion of the woman's silk gown (fig. 9) subtly reinforces the representation of the large-scale painting of a Cupid which hangs on the back wall in an ebony frame. It is similar to the fishing Cupid in a print from Hooft's Emblemata amatoria (fig. 8). "Hooft's emblem plays on the conventional comparison of courtship to fishing. In Vermeer's Cupid tile, the fishing rod is visible, the proportions of the figure are consistent with Cupid, and the dark shape on his back can only be his stubby wings. (The same figure may be repeated on a tile to the right, partially obscured by the virginal's leg.) Prints like that from Hooft's book often served as patterns for tiles. Contemporary viewers who were familiar with these recurring designs on their own walls would readily have identified the Cupid in Vermeer's tile."Nevitt Jr., H. Rodney. "Vermeer on the Question of Love." In The Cambridge Companion to Vermeer (Cambridge Companions to the History of Art), edited by Wayne Franits, 98. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Emblemata amatoria (1611)

Pieter Cornelisz. Hooft

Fig. 9 (right) A Lady Standing at a Virginal (detail)

c. 1670–1674

Oil on canvas, 51.7 x 45.2 cm.

National Gallery, London

Fig. 10 Delft baseboard tiles featuring children playing games

Fig. 10 Delft baseboard tiles featuring children playing gamesFrans Hals Museum

Haarlem