John Michael Montias was an American economist who became one of the foremost Vermeer scholars. Via a scrupulous analysis of a paper trail of note, letters, receipts, and legal documents, he was able to peel back the layers of the lives of Vermeer and his extended family, opening the door for a new genre of art history in which artists are analyzed in the context of their societal and economic surroundings, rather than merely their work (Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History, 1989).

Among his many discoveries, Montias revealed that there was at least a small number of people who acquired Vermeer's paintings during his lifetime or shortly thereafter, and that at least one of these, a wealthy collector named Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven, may be rightly called a patron or Maecenas. Montias believed that Van Ruijven and his wife, Maria Simonsdr de Knuijt, may have protected Vermeer and his family during his lifetime from the vicissitudes of the national economy. Montias's position on Van Ruijven, however, has recently been revised to the effect that many now see De Knuijt as the principal collector, given she is known to have had an active interest in art and had a much closer relationship with the Vermeer family, having grown up just a few doors away from the Vermeers' house called Mechelen. Moreover, she had brought to her marriage a considerable inheritance.

Below, in alphabetical order, is a list of those individuals known to have bought one or more paintings from Vermeer, with a commentary for each.

A Brief Overview of Vermeer's Clients and Patrons

Frans van Mieris

1660

Oil on oak, 54,5 cm × 42,7 cm.

Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Gemäldegalerie, Vienna

After reviewing all surviving records concerning Vermeer's professional life, two facts are apparent. First, the artist's paintings commanded relatively high prices compared to those of the majority of his most esteemed Dutch contemporaries in the genre mode. The price of 600 livres (probably meaning guilders) that a Delft baker thought reasonable for one of his paintings with a single figure appears in line with the six hundred livres asked by Gerrit Dou (1613–1635) for his Woman in a Window to the Frenchman Balthasar de Monconys (1611–1665). However, it should be kept in mind that it's not out of the question that the baker made an attempt to impress a well-to-do foreigner or, being a practical man, might have purposely inflated the price for the sake of bargaining. Furthermore, the works of Dou or Frans van Mieris (1635–1681) could occasionally reach 800 to 1,000 guilders, or even more if the purchaser happened to be a prince. In 1660, Van Mieris's Cloth Shop (fig. 1) was bought by the Archduke of Tuscany for the astonishing price of two thousands guilders. In those days, one could acquire a reasonable house for one thousands guilders, and it was rare for a painting to fetch more than fifty guilders.

Moreover, in the Amsterdam auction of 21 twenty-one works by Vermeer in 1696—Vermeer died in 1675—the highest price fetched for a single-figured work (The Milkmaid) was only 175 guilders, while the monumental View of Delft went for a "mere" two hundred guilders. Cornelis de Helt, who died fourteen years before Vermeer, had acquired a picture whose value was esteemed at twenty guilders and ten stuivers when it was sold in the estate sale the year of De Helt's death. The relatively low price of the work could have depended on various factors, including its dimensions or subject matter. Even tronies of the most important Dutch painters were sold for comparable sums. In addition, a painting by Vermeer owned by the sculptor Johan, Jean, or Johannes Larson was auctioned for ten guilders in 1664, although it was described as "a principal by Van der Meer," thereby emphasizing that this was an original work by the Delft master. This could suggest the painting was a small-scale work or, alternately, that the six hundred guilders quoted by Van Buyten for his single-figure work were wildly exaggerated. To muddy the waters further, in 1699, the Allegory of Faith, which today is not considered among the artist's most inspired compositions, was sold to Herman Stoffelsz van Swoll for the respectable sum of four hundred guilders a few years later. And more importantly, perhaps, when the Dissius collection was auctioned in Amsterdam in 1696, not a single one of the listed twenty-one Vermeer paintings fetched the high price Van Buyten had found appropriate many years earlier.

Thus, the limited evidence available today may suggest that the prices of Vermeer's paintings may have fluctuated over a relatively short period of time, perhaps due to imponderable factors.

Nonetheless, it appears apparent that Vermeer sold his paintings to a handful of affluent individuals who were capable of recognizing the extraordinary quality of his art, despite the fact that his fame was not nearly as widespread as that of the most renowned Dutch masters of the time. It appears likely that Vermeer's fame did not reach much farther than nearby The Hague or Amsterdam.

There is considerable evidence that Vermeer worked for the upper echelon of Delft society. Van Ruijven and his wife, Maria de Knuijt, were very wealthy Delft patricians who could purchase any paintings they wished without making a dent in their finances. When Hendrick van Buyten, a baker who owned four Vermeers, died, he left the astronomical sum of 28,829 guilders, one of the largest sums Montias had uncovered in Delft archives. He had accepted two pictures from the painter's widow as security for a debt of more than six hundred guilders, which demonstrates not only that Vermeer had encountered financial difficulties toward the end of his life but also that his paintings commanded steep prices.

Even those occasional clients who had acquired only a single work by Vermeer belonged to the upper class. The Delft patrician Willem van Berckel was a "Commissioner of the Finances of Holland." Nicolaes van Assendelft, a Delft regent, was known to have assembled a remarkable art collection that included numerous major Dutch masters. Another occasional collector, Johannes de Renialme, who had frequent dealings in Delft but lived in Amsterdam, was an affluent art dealer. Diego Duarte was an immensely wealthy banker and diamond dealer from Antwerp who had formed a huge collection of paintings. His love for the arts brought him into contact with Constantijn Huygens, a veritable Dutch Renaissance man, and other members of the international cultural elite. Twenty years after Vermeer's death, one of the richest men in Amsterdam, Jacob Oortman, purchased the Mistress and Maid at the Dissius auction of 1696.Franz Grizenhout, "Een schrijfstertje van Vermeer. Jacob Oortman en de Dissiusveiling van 1696," Oud Holland 123, no. 1 (2010).

Although some points regarding the nature of Vermeer's relationship with his patrons Van Ruijven and Maria de Knuijt are subject to scrutiny, it seems almost certain that the art-loving couple had acquired a number of works directly from Vermeer. In fact, Van Ruijven's son-in-law, Jacob Dissius, had twenty Vermeers in his home at the time of his death, which he had inherited through his marriage to Van Ruijven's daughter, Magdalena. If we accept Montias' estimate of the total number of works from Vermeer, ranging from fourty-four to fifty-four, Van Ruijven and his wife had acquired approximately half of Vermeer's entire artistic output.

Montias firmly believed that "the relationship between Van Ruijven and Vermeer went clearly beyond the routine contacts of an artist with a client." Van Ruijven lent Vermeer money. He witnessed the will of Vermeer's sister Gertruy in her own house shortly before her death. More significantly, Maria de Knuijt left Vermeer a conditional bequest of five hundred guilders in her wil, a sizable amount that might buy a small house. Such a third-person bequest was extremely unusual at the time.

The eminent Vermeer scholar Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. expressed doubts about the exact nature of Vermeer's and Van Ruijven's relationship. "The hypothesis that Van Ruijven was Vermeer's patron, although appealing, should be cautiously approached, for no document specifies that Vermeer ever painted for Van Ruijven. Moreover, no source confirms that Van Ruijven himself had any Vermeer paintings in his possession. While Van Ruijven may have acquired paintings from Vermeer, it seems unlikely that he assumed such an important role in the artist's life as Montias suggests. Should Van Ruijven have been Vermeer's patron, one would expect that the French diplomat Balthasar de Monconys would have visited Van Ruijven himself in 1663, rather than the baker, Hendrick van Buyten, upon hearing that Vermeer had no paintings at home. Similarly, the Vermeer enthusiast Pieter Teding van Berckhout would also have made an effort to see the Van Ruijven collection in 1669 on his two visits to Delft." Wheelock further states: "While it is probable that some of the twenty Vermeer paintings listed in the inventory of 1683 (the inventory taken after the death of Van Ruijven's daughter) came from Van Ruijven, others may have been acquired by his daughter Magdalena, Jacob Dissius, his son-in-law, or his father, Abraham Jacobz Dissius, at a sale of twenty-six paintings from Vermeer's estate held at the Saint Luke's Guild Hall on May 15, 1677."Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Ben Broos, Johannes Vermeer (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 23.

Nicholas van Assendelft

Jacob Willemsz. Delff

1619

Oil on canvas, 97 x 275 cm.

Museum Het Prinsenhof, Delft

Nicholas van Assendelft (1630–1692) was a Delft alderman and member of the Council of Forty who had assembled a large art collection containing many works by the most important Dutch masters. His collection included a portrait of himself painted by the fashionable Johannes Verkolje (1650–1693), as well as works by Jan Steen (c. 1625–1679), Adriaen van Ostade (1610–1685), and Philips Wouwerman (1619–1668).

He was the eldest son of the notary Willem Claeszn van Assendelft, portrayed as a sergeant on the militia piece called The Officers of the White Flag (fig. 2 & 3), painted by Jacob Willemsz. Delff in 1648 and present in the Museum Het Prinsenhof in Delft.

In 1657, he married Agnetha Hendricksdr van Mierop (1630–1667), with whom he had a son, Willem Nicolaeszn. In 1668, eleven years after the death of Van Mierop, he married Maria Magdalena Willemsdr van der Hoeff, sister of Adriaen Willemszn van der Hoeff (1624–1711), who was also a Delft alderman. He was one of the judges who decided on the disposition of Vermeer's estate.

In February 1677, in his role as Lord Alderman of the town of Delft, Van Assendelft approved the agreement between the curator of Vermeer's estate, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, and the spinster Jannetje Stevens, a merchant to whom Vermeer had accrued significant debts. The dispute involved the twenty-six paintings that the artist Jan Colombier had bought from Vermeer's widow, Catharina, to help settle an estate debt with Stevens. It was ruled that the paintings would return to the estate to be sold, and the merchant would be repaid by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek with 347 guilders. The auction of the paintings was scheduled to take place on May 15 at the premises of St. Luke's Guild Hall. In the agreement, it was established that if the proceeds exceeded 347 guilders, the excess up to five-hundred guilders would go back into the estate. Little is known about those twenty-six paintings: who and how many were the authors, their subject, who bought them at the auction held in May 1677, or how much they were sold for.

Jacob Willemsz. Delff

1619

Oil on canvas, 97 x 275 cm.

Museum Het Prinsenhof, Delft

Nicolaes van Assendelft died in December 1692, and Maria Magdalena van den Hoeff survived him for nineteen years.

In the 1711 inventory of the property of Van Assendelft's widow, there appeared "Een juff.r spelende op de Klavecimbel door Vermeer" (A lady playing the clavichord, by ditto), appraised at forty guilders. This description is very similar to that of number thirty-seven in the Dissius sale "Een Speelende Juffrouw op de Clavecimbaerl van dito" (A young woman playing the clavichord, by ditto). The term "Juff.r" or "juffr." is likely an abbreviation for "juffrouw." The valuations of the two works are also very similar: forty guilders for the first, and forty-two guilders and ten stuivers for the other. In seventeenth-century Dutch documents, especially handwritten ones, abbreviations were often used to save space and time.

There is no proof that Van Assendelft bought the painting directly from Vermeer, but this is not out of the question. It is not known whether Van Assendelft's widow continued to expand the inherited collection in these years. In this case, she might have purchased the painting of the virginal player during or after the Dissius sale.

The description of Van Assendelft's Vermeer could fit one of two extant works, A Lady Seated at a Virginal (fig. 4) or A Lady Standing at a Virginal (fig. 5), both in The National Gallery of London. However, there may have once existed another painting(s) by Vermeer that could match the succinct inventory description.

Thus, Van Assendelft can be considered an occasional buyer of Vermeer rather than a client or patron.

In January 1640, Van Assendelft's father, Willem van Assendelft, visited Vermeer's father, Reynier Jansz. Vos, twice to discuss matters related to Reynier's house named Mechelen. The first visit was to collect overdue and future rent. During the second visit, he inquired whether Reynier was interested in purchasing the dwelling. Reynier, however, stated that he did not wish to buy the house and preferred to stick to his current lease, which had one more year to run before expiring.

Of William van Assendelft's twelve children, Gerard, like his father and brother Nicholaes, was also a notary. On January 27, 1776, Catharina Bolnes, the widow of the late painter, appeared Gerard. She declared the sale and transfer of two paintings by Vermeer to Hendrick van Buyten, a master baker in Delft. One painting depicted two people, one writing a letter, and the other with a person playing the lute. The sale price was 617 guilders and six stuivers, which was the amount Bolnes owed to Van Buyten for bread he had supplied. The agreement included a condition that the debt would be considered null and void.

Furthermore, the agreement stipulated that if Bolnes paid Van Buyten fiftey guilders annually on May 1, starting in 1677, until the full amount of 617 guilders and six stuivers was repaid, she could reclaim the paintings. Additionally, 109 guilders and five stuivers were also due for previous bread deliveries. If Bolnes' mother passed away before the debt was fully repaid, any remaining balance would have to be paid at a rate of two hundred guilders per year, including an interest of four percent per annum from her mother's death until full settlement. If Bolnes failed to pay the fiftey guilders annually as agreed, the same interest would apply.

In the event of complete repayment, Van Buyten would be obligated to return the two paintings to Cahttharia or her heirs. The contract also mentioned that Van Buyten agreed to this restitution arrangement after being moved by Bolnes' earnest request and persistent urging. If Bolnes failed to meet her obligations, van Buyten was permitted to sell the paintings. The solicitors for Bolnes were Floris van der Werff and Philippus de Bries. A second version of the contract included minor changes, emphasizing Van Buyten's decision to agree to the restitution settlement due to Bolnes' serious plea and urgent persistence.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1673

Oil on canvas, 51.7 x 45.2 cm.

National Gallery, London

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1675

Oil on canvas, 51.5 x 45.5 cm.

National Gallery, London

Willem van Berckel

On March 24, 1716, a now-lost history painting, presumably from the beginnings of Vermeer's career entitled "Jupiter, Venus en Mercurius door J. ver Meer" (Jupiter, Venus and Mercury by J. ver Meer) was auctioned in Delft from the estate of the Delft patrician Willem van Berckel (c. 1620–1686). Willem's collection had been formed earlier in the century by his father, Gerard van Berckel (c. 1620–1686), a one-time burgomaster of the city of Delft, who may have acquired the work himself before his death. "This mythological scene, presumably in possession of the distinguished Delft family for a long time, may be considered evidence of the interest in Vermeer's work in the upper social strata of Delft society."Wheelock and Broos, Johannes Vermeer (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 48. Since the picture was listed in the inventory of 1657, it must have been created in or before this year, when Vermeer was in his early twenties. However, the painting is lost and no description or visual record of it is known.

Initially, Montias held that Diana and Her Companions represented Vermeer's only foray into mythology since Jupiter, Venus and Mercury do not appear jointly in any known subject drawn from mythology. In any case, the title given to Van Berckel's Vermeer by the auctioneer may have been a misnomer, for this kind of subject almost always featured Virtue or Psyche rather than Venus. According to Montias, if this painting was by Vermeer, it surely would have been executed early in his career to complement the mythological theme of Diana and Her Companions.

"Dosso Dossi's painting of Jupiter, Mercury and Virtue (shown as a female figure) is conserved in Vienna (fig. 6). Raphael is known to have made a drawing of Mercury introducing Psyche to Jupiter."John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 140.

However, Michiel C. Plomp revealed the existence of "a drawing (fig. 7) by the Delft painter Leonaert Bramer (1596–1674) after a painting by Jacob Jordaens (1593–1678), the subject of which is taken from the legend of Psyche in Apuleius's Golden Ass. It shows a jealous Venus complaining to Jupiter in Mercury's presence about Psyche's charms. This unpublished drawing...was once part of the album of about 110 drawings made by Bramer after paintings that belonged to Delft collectors in 1652–1653. It is quite possible… that Vermeer had seen the Jordaens painting not long before he painted his own version of the subject (presumably before 1656, the date of The Procuress, his first genre painting). The Jordaens composition would have appealed to his own interest in women attending, or deferring to men (as in Christ in the House of Martha and Mary)."Montias, "A Postscript on Vermeer and His Milieu," Mercury, 1991.

The young and ambitious Vermeer may have painted this mythological scene and the Diana in response to the prevailing classical tastes of the Dutch court in the rich and nearby The Hague.

Dosso Dossi

c. 1480–1490

Oil on canvas, 111.3 x 150 cm.

Collection, Wawel Castle, Krakow

Leonaert Bramer after Jacques Jordaens

c. 1652−1653

Black chalk on paper, 29.2 x 34.6 cm.

Cambridge MA, Estate of Seymour and Zoya Slive

Hendrick van Buyten

Hendrick Ariaensz. van Buyten (1632–1701) was a prosperous boulanger (baker), head of the Bakers' Guild in 1668, and a prominent Delft citizen. He owned a house on the south side of Choorstraat and possibly also one on Delft's most prestigious street, Oude Delft. On Koornmark, he owned two more houses: one on the east side In het Witte Paert (In the White Horse), sold in 1683, and one on the west side De Gulden Cop (The Golden Cup) at number thirty-one.Kees Kaldenbach, "Nicolaes Assendelft, Vermeer Patron," http://kalden.home.xs4all.nl/dart/d-p-assendelft.htm. Van Buyten was born in the same year as Vermeer. After losing his first wife, named Machtelt van Asson (a baker's daughter), he married Adriana Waelpot in November 1683. Adriana's father owned an important printing press in Delft, comparable to that of Abraham Dissius, whose son would inherit twenty paintings by Vermeer. In contrast to Pieter van Ruijven, Vermeer's principal patron, along with his wife Maria de Knuijt, Van Buyten came from fairly humble origins. His father, Adriaen Hendricksz. van Buyten, was a shoemaker.

We know Van Buyten owned at least three paintings by Vermeer, more likely four. It is remarkable that all five of the painters cited in Van Buyten's inventory—Vermeer, Bramer, Anthony Palamedes, (Nicholas) Bronckhorst, and Pieter van Asch—were born in Delft, became masters of the local guild, and died in Delft. Thus, compared to the Van Ruijven-Dissius collection, Van Buyten's appears to have been somewhat provincial and old-fashioned.Montias, "Vermeer's Clients and Patrons," The Art Bulletin 69, no. 1 (March 1987): 75.

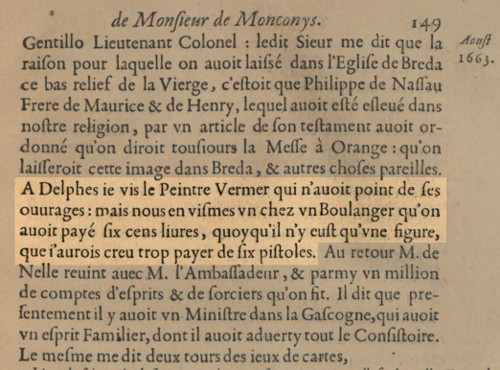

In August 1663, after claiming he had nothing to show him in his own studio, Vermeer directed the French Catholic, traveler, diplomat, physicist, and magistrate Balthasar de Monconys (1611–1665) to the home of Van Buyten to see a single picture. After visiting De Buyten, De Monconys wrote in his diary journal, later published in 1666, the year of his death: "In Delft I saw the painter Verme(e)r who did not have any of his works: but we did see one at a baker's, for which six hundred livres (probably guilders) had been paid, although it contained but a single figure, for which six pistoles would have been too high a price (fig. 7) (about ten times less than the six hundred guilders)." Curiously, "no one has yet explained why De Monconys was steered to Van Buyten, who apparently had only one picture by him, rather than to Pieter van Ruijven, who presumably had at least a half-dozen of them by this time: the baker, being a tradesman, was more likely to sell than the patrician."Montias, "Vermeer's Clients and Patrons," The Art Bulletin 69, no. 1 (March 1987): 74.

According to Montias, "Monconys's observation that Vermeer had no paintings to show him would seem to imply that the artist had no stock in trade. Unlike many other Dutch painters of the period who produced "on spec" and kept at least some of their works in their atelier in the expectation that clients and visitors would choose and buy those they liked from the available stock, Vermeer by this time probably worked mainly on commissions or at least on paintings he thought he had a good chance to sell to one of his clients or patrons. As I shall attempt to show..., he painted so slowly completing only two to three paintings a year that he could not operate like many of his contemporaries, who had enough paintings on hand to garnish their walls. In this respect, as well as in some others, he resembled Gerrit Dou, Frans van Mieris, and the other 'fine painters' of his day who also worked mainly on commission."Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 181.

du Roy en ses Conseils d'Estat & Privé,

& Lieutenant Criminel au Siège Presidial de Lyon

Balthasar de Monconys

2 vols., Lyon, 1665–1666. page 148–149

In any case, two days later, de Monconys was quoted the same price for a single-figure painting by the renowned highest painted Dutch fijnschilder (fine painter) Gerrit Dou, whose patron, Johan de Bye (also visited by the Frenchman), had purchased more than two dozen of his precious works. Montias has speculated that the exorbitant price asked by Van Buyten for his one-figure Vermeer may have been inflated for the sake of bargaining. The picture which had scandalized de Monconys could have been one of various surviving single-figured compositions by Vermeer, as well as a painting that has not survived.

In a disposition of January 1676, a month and a half after Vermeer's death, the artist's wife, Catharina, appeared before a notary to acknowledge that she had sold and transferred two paintings by her late husband to Van Buyten. Catharina further declared that she had been paid 617 guilders for the two paintings, which she owed to Van Buyten for bread delivered. He would return the paintings, "two persons, one of whom is sitting writing a letter" (fig. 8?) and "a person playing on a cittern" (fig. 9?) if she paid all her debts. It would appear that Van Buyten retained the former pictures until his death in 1701, after which they were acquired by Josua van Belle (d. 1710), a merchant in Rotterdam. The late Dutch art scholar and Vermeer specialist Walter Liedtke suggested that the former picture may now be lost, because "the chances of it being identical with the Dissius painting are remote, for several reasons."Walter Liedtke, Vermeer: The Complete Works (London, 2008), 172.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1671

Oil on canvas, 71.1 x 58.4 cm.

National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1673

Oil on canvas, 53 x 46.3 cm.

Iveagh Bequest, London

Diego Duarte

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1675

Oil on canvas, 51.5 x 45.5 cm.

National Gallery, London

Diego Duarte (1612–1691) was an immensely wealthy Portuguese jeweler/banker from Antwerp, as well as an accomplished organist and composer. Besides music, however, Duarte had other artistic interests.

Perhaps following in the footsteps of his father, Duarte became a fervent collector of paintings. His collection is mentioned several times in reports from travelers who passed through Antwerp, such as de Monconys, Constantijn Huygens, and the Swedish architect Nicodemus Tassin (1687). The visitors invariably praised the collection's Italian paintings by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century masters such as Raphael, Titian, and Tintoretto, as well as seventeenth-century Flemish paintings, especially those by Rubens and Van Dyck.

In 1682, Duarte composed a catalog of his collection. It provides not only insights into the formation of the collection but also the prices he paid for his paintings and, in some cases, their provenance. As a discerning art connoisseur, he also possessed "Een stuckxken met een jouffrou op de clavesingel spelende met bywerck van Vermeer kost guld. 150" (A young lady playing the clavecin with accessories, by Vermeer, valued at 150 guilders). Ben Broos speculated that either Constantijn Huygens Jr. or Senior may have given Diego Duarte of Antwerp one of Vermeer's late works, possibly the Lady Seated at the Virginal, (fig. 10) or at least advised him to buy it. If so, it was the first Vermeer to leave Dutch hands that we know of. However, according to Wheelock, several facts argue against such a hypothesis. If Duarte owned only one of the two works by Vermeer considered pendants—Lady Standing at the Virginals and Lady Seated at the Virginal—works, "they almost certainly would not have been separated at such an early date."

Duarte maintained a lengthy correspondence and friendship with Constantijn Huygens, one of the most influential diplomats and cultural figures of seventeenth-century Netherlands. Like the sculptor Johan Larson, who had purchased a tronie from Vermeer, Huygens lived in The Hague.

Duarte's house in Antwerp was known as the Antwerp "Parnassus (fig. 11)," a meeting place for his family (fig. 12) and intellectuals to enjoy art and music. William III of England (1650–1702) repeatedly stayed at the house between 1674 and 1678. Diego's brother Gaspar Duarte II was also an art collector, and his sister Leonora was a composer. Among Duarte's sisters, Francisca, nicknamed Rossignol Anversois (Antwerp Nightingale), was frequently mentioned in the correspondence of both Constantijn and his brother Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695), known for his scientific discoveries. From Constantijn's letters from the 1630s, we learn that she sang duets with Maria Tesselschade Roemers Visscher (1594–1649; nicknamed Tesseltjen), accompanied by the Delft composer Dirk Janszoon Sweelinck (159–1652), son of the Amsterdam composer and organist Jan Pieterszoon, at the harpsichord. The beauty of this unique vocal combination inspired Huygens's brother-in-law to compose an epigram in their honor, Ad Tesselam and Duartam cantu nobiles.

Gonzales Coques

c. 1644

Oil on canvas, 65.8 x 89.5 cm.

Szepmueszeti Muzeum, Budapest

Photograph Antwerp, City Archives

Duarte's inventory of his stock of some two hundred paintings is now in the Royal Library in Brussels. It was published by Frederick Muller in 1870.[Frederick Muller], "Catalogus der schilderijen van Diego Duarte, te Amsterdam in 1682, met de prijzen van aankoop en taxatie," De Oude Tijd (Haarlem, 1870), 397–402.. The assumption that Diego Duarte lived in Amsterdam was not warranted, and a revised version by Mr. G. Dogaer was republished in 1971.G. Dogaer, "De Inventaris der schilderijen van Diego Duarte," Jaarboek van het Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, 1971, 195–224..

At the time of the 1683 inventory, Duarte's stock of paintings had been valued at over 38,000 fll. At the time of his death, the collection was smaller by perhaps a third, but its value was still substantial.

Duarte left no children. Some two hundred of his paintings were inherited by his nephew Manuel Levy Duarte. Most were sold between 1693 and 1696.

Cornelis Cornelisz. de Helt

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 73.3 x 64.5 cm.

The Royal Collection, The Windsor Castle

Cornelis de Helt (?-1661) was a cooper and innkeeper in Delft. In his estate (May, 1661), a Vermeer painting was listed "Int Voorhuys [:] In den eersten een schilderye in een swarte lyst door Jan van der Meer" ("In the front parlor [:] Firstly, a painting in a black frame by Jan van der Meer) of the Young Prince Inn. On the following June 14, the painting was auctioned for twenty guilders and ten stuivers. While this sum was adequate (in 1642, a Delft cloth-worker earned close to one guilder a day) for a painting in those years, it does not compare with the sum of six hundred guilders that the Delft baker Van Buyten claimed his Vermeer was worth to the skeptical de Monconys.

Nothing can be deduced from the meager description of the painting by Vermeer, who, like many other Dutch painters, used black (ebony or ebonized) frames, a few of which hang on the back walls in his own compositions. Ebony frames were also used for mirrors (see The Music Lesson; fig. 13). Dutch frame-makers were known for their ability to imitate costly exotic woods. Incidentally, the husband of Vermeer's sister, Gertruy, was a frame maker. The subject matter of this painting remains a mystery.

Johan (Jean) Larson

Johan Larson (after)

c. 1680-1700

Gilt-lead, h. 50,2 cm.

Amsterdams Historisch Museum, Amsterdam

Johan, Jean, or Johannes Larson (?–1664) was a sculptor who worked in London and The Hague. He was born into a family of artists active in the first half of the 17th century in London and The Hague. Given their name, the Larsons probably came from Sweden, although no clear traces of their origins have been found there. Larson was another friend of the well-connected Constantijn Huygens.

In an inventory of Larson's goods drawn up on August 4, 1664, a painting described as "Een tronie van Vermeer" (a tronie by Vermeer) was listed. This is the earliest date assigned to any of the four known, and six cited, in 17th-century inventories. The painting was valued at ten guilders. Montias suggested that he may have purchased this painting directly from Vermeer during a business trip to Delft in 1660.

Given the almost sculptural torsion of the figure, Larson may have purchased Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Earring.

When Larson died, Vermeer was thirty-two years old and had recently been headman of the Guild of Saint Luke in Delft twice already.

Johannes de Renialme

Johannes de Renialme (c. 1600–1657) was a prosperous art dealer registered in the Delft guild of artists and artisans. He had traded works by Rembrandt, Hercules Segers, and Jan Lievens, among others, and counted Friedrich Wilhelm, the Great Elector of Brandenburg, as a client. In his estate, there was a painting by Vermeer described as "Een graft besoeckende van der Meer 20 gulden" (a picture of the grave visitation by Van der Meer, twenty guilders). Its value was assessed at twenty guilders, which is not an unreasonable price for a work by a relatively young painter (Vermeer was 24 years old in late 1656).

It remains unclear, however, whether the words "grave visitation" describe a biblical, New Testament theme (fig. 14), showing the visit of the three Maries to the tomb of Christ on Easter Sunday, or alternatively, to a contemporary scene depicting the tomb of William of Orange in Delft's New Church (fig. 15). The tomb was a major attraction and the subject of many paintings and drawings.

De Renialme worked in Amsterdam but also maintained close contacts with Delft, where he bought paintings regularly. He also had a house in Delft and was registered as an art dealer in Delft's Guild of Saint Luke in 1644. When De Renialme died in 1657, he left four hundred pictures, many of which can be found in famous collections today, such as Rembrandt's Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery. In addition to works by Rembrandt, a great number of notable painters of the past and of the time were part of his art collection, including those of Ter Borch, Steen, Potter, Hals, Dou, Rubens, Titian, Bassano, Holbein, and Claude Lorrain.

Annibale Carracci

c. 1604

Oil on canvas, 92.8 x 103.2 cm.

National Gallery, London

Delft, with the Tomb of

William the Silent

Gerard Houckgeest

1650

Oil on panel, 126 x 89 cm.

Hamburg, Kunsthalle

Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven and Maria Simonsdr de Knuijt

Pieter van Ruijven (1624–1674) was a wealthy Delft burger who inherited his fortune from his family's brewery investments. For many years, he had been almost unanimously accepted as Vermeer's primary, and perhaps only, patron. However, recent research suggests that Van Ruijven's wife, Maria de Knuijt (1623–1681), may have played a far more important role than previously understood.

The art historian Judith Noorman, an Associate Professor at the University of Amsterdam and the Principal Investigator of the The Female Impact Project, maintains that De Knuijt not only influenced Vermeer's choice of subject matter but may have also been instrumental in acquiring nearly half of Vermeer's known output. She may have influenced the artist's decision to pivot from the history mode of painting of his early career to the more genteel genre mode for which Vermeer is universally appreciated today.

Recent research and interpretation by Noorman and Piet Bakker has culminated in the study "Women’s Vermeers: Maria de Knuijt and New Archival Documentation on Vermeer’s Primary Patron,Piet Bakker and Judith Noorman, "Women's Vermeers Maria de Knuijt and New Archival Documentation on Vermeer's Primary Patron," in Closer to Vermeer: New Research on the Painter and His Art, ed. Anna Krekeler, Francesca Gabrieli, Annelies van Loon, and Ige Verslype (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum / Veurne: Hannibal Books, 2025). challenging the long-held notion that Pieter van Ruijven and his wife, Maria de Knuijt, jointly formed the central collecting force behind Vermeer's career. For decades, the couple had been treated as a unit, with Pieter cast as the principal patron who purchased a substantial portion of Vermeer's output and provided the economic stability that allowed the painter to pursue his distinctive artistic path. The new archival findings complicate this picture in important ways and propose that Maria de Knuijt herself played the leading role in acquiring Vermeer's paintings.

A crucial clue lies in a rediscovered entry from 1665, in which Maria bequeaths a sum of two hundred guilders to Vermeer. It is highly unusual for a woman to make such a bequest to a non-relative, and even more so when no comparable gift from her husband survives. This single documented act establishes a direct, personal connection between Maria and Vermeer, suggesting a relationship grounded in admiration or sustained patronage. When viewed in the context of the paintings later found in the Van Ruijven–De Knuijt collection, the bequest signals that Maria may have been the motivating agent behind the couple’s acquisitions.

Other newly examined documents reinforce the impression that Maria operated as an independent economic actor. Her inheritance, her management of family funds, and her legally recorded decisions reveal a woman fully capable of directing purchases in her own right. Moreover, patterns in the couple's estate—particularly the manner in which Vermeer paintings were transferred to their daughter Magdelena—align more naturally with Maria's documented preferences and financial behavior. While Pieter certainly participated in the household#39;ss collecting habits, the evidence suggests, accpording to Bakker and Noorman, that the initiative, taste, and possibly the sustained loyalty to Vermeer originated soundly with Maria.

This revised view reshapes our understanding of Vermeer's professional environment. Rather than depending on a male patron who quietly ensured his livelihood, Vermeer may have been supported over many years by a woman of discernment whose engagement with his work was both personal and deliberate. The implications extend beyond biography. If Maria was indeed the driving force, her preferences may help explain Vermeer's focus on interior scenes centered on women—images marked by quiet introspection, domestic authority, and subtle emotional states. While this connection cannot be proved, it gains plausibility when set alongside the new archival picture of a knowledgeable female collector with a clear affinity for Vermeer’s subjects.

In presenting Maria de Knuijt as Vermeer's primary patron, the recent research invites a broader reconsideration of the painter’s social and economic network, the role of women as cultural agents in the Dutch Republic, and the motivations that sustained Vermeer’s finely crafted paintings across two decades.

In any case, the Van Ruijvens would likely have considered themselves as Liefhebbers van de Schilderkonst (Lovers of the Art of Painting), a fast-growing but distinct group of people interested in art and artists, composed principally of members from the upper classes.

Given their economic status as patrons, it is tempting to imagine that the Van Ruijvens visited Vermeer's studio and conversed with him about the fine points of the art of painting. Despite the lack of direct documentary evidence that the Van Ruijvens collected Vermeer's work, circumstantial evidence links their names to the twenty-one paintings of Vermeer sold at the Dissius auction held in Amsterdam in 1669. As Montias has shown, the Van Ruijvens most likely acquired the bulk of this collection directly from the artist. It is generally accepted that the Van Ruijvens' collection was inherited by Jacob Dissius through his marriage to Van Ruijven's daughter, Magdalena. Upon Dissius's early death, the entire collection was auctioned in Amsterdam in 1696, which is crucial for understanding the market value and demand for Vermeer's works during the late seventeenth century. Additionally, the Dissius auction catalog serves as an important historical artifact, documenting the existence of several Vermeer paintings that are now lost or have not yet been identified. It provides a glimpse into Vermeer's artistic output beyond the works that have survived to this day.

It is believed that Van Ruijven became wealthy through his shrewd investments. He died in 1674, about sixteen months before Vermeer.

However, according to some Vermeer experts, such as Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., the speculation that Van Ruijven was an intimate patron of Vermeer's work should be cautiously approached and it is not out of the question that "despite the near steady income that Vermeer possibly depended upon from Van Ruijven, this arrangement could also have been injurious. If indeed a significant proportion of Vermeer's works remained in the family collection until twenty-two years after Van Ruijven's death, the question can be legitimately raised as to whether this limited the spread of the artist's reputation beyond his native city. There is, however, increasing evidence that Vermeer's circle of buyers and devotees, albeit limited, stemmed from the very upper echelons of society in Delft and beyond. For example, two other members of the patrician class (one of the wealthiest and most august social groups in the Netherlands) in Delft, Gerard van Berckel and Nicolaes van Assendelft, likely owned paintings by Vermeer."Wayne Franits, "An Overview of His Life and Stylistic Development," in The Cambridge Companion to Vermeer, ed. Wayne E. Franits (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 19.

More about Pieter van Ruijven

In 1669, Van Ruijven paid 16,000 guilders—an astronomical sum—to acquire land near Schiedam that brought with it the title of Lord of Spalant. His acquisition may be considered a case of "social rising," a phenomenon already underway by the end of the sixteenth century and that reached its climax during the economic boom of the decades following the Treaty of Munster. Van Ruijven's father had owned a brewery, "The Ox," on the Voorstraat, which closed down in the mid-1650s. It was one of many Delft breweries to succumb to out-of-town competition. "He was related to some of Delft's most prominent families including the Van Sanitens and the Graswinckels. His cousin Jan Hennansz. van Ruijven married Christina Delft, the sister of the painter Jacob Delft, who was the son of the engraver Willem Delft and the grandson of the portrait painter Michiel van Miereveld. It was perhaps because some of the Van Ruijvens had been accused of Remonstrant sympathies in the aftermath of the Oldenbarnevelt episode that they were barred from the highest municipal posts."Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 246.

He married well in August 1653 to Maria de Knuijt, who brought with her a considerable inheritance. It's likely that her preferences were considered, and more than one specialist believes she may have influenced, to some degree, the choice of subjects in Vermeer’s paintings. They eventually owned at least three Delft houses: two in the Voorstraat and one on Oude Delft, the city's most prestigious street, in a house called "Den Gouden Arent" (The Golden Eagle), valued in 1671 at 10,500 guilders. One of the Voorstraat houses was damaged in the Delft Thunderclap, and Van Ruijven claimed compensation for it.

Later, the Van Ruijvens moved to the Oude Delft house. Though they were living in The Hague in July 1671, they apparently moved back to Delft, to the Voorstraat, shortly before Van Ruijven's death at the age of forty-nine, in 1674. Vermeer died one year later. In 1657, Van Ruijven loaned Vermeer and Catharina two hundred guilders, perhaps expecting to receive paintings in return. In 1665, Maria de Knuijt bequeathed Vermeer, excluding Vermeer's wife Catharina, a legacy of five hundredguilders. From 1668 to 1672, Van Ruijven served as the master of the "Camer van Charitate" (the municipal chamber of charity), just as his father, a brewer, had in the 1620s. The Van Ruijvens were sympathetic to the Remonstrants, which, given the political realities of the time, excluded them from the higher civic offices they otherwise would probably have served in.

Montias has argued that De Knuijt ensured that only Vermeer, and not his Catholic wife, would benefit from it if Catharina survived him. But it may be too much to read any anti-Papist or anti-Jesuit sentiment into this, particularly if Vermeer himself was regarded as a more-or-less converted Catholic. Maria may simply have wanted to assist the artist professionally, and not provide funds for his relatives after his death. The friendship her husband Pieter felt for the Vermeer family seems evident in the fact that, in 1670, he witnessed the last testament of Vermeer's sister Gertruy and her husband, the picture-framer Antony van der Wiel, who were described as well-known to the notary and the witnesses.

Please note that there exists absolutely no historical evidence that would suggest that Pieter van Ruijven was a predatory lecher as he was portrayed in the fictional movie Girl with a Pearl Earring, based on Tracy Chevalier's novel of the same name.

Herman Stoffelsz van Swoll

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1674

Oil on canvas, 114.3 x 88.9 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Herman van Swoll (1632–1698) was the Protestant Amsterdam postmaster of the Hamburg mail service. At least according to his estate, which was settled on April 22, 1699, he had acquired Vermeer's Allegory of Faith (fig. 16) possibly directly from a (Delft?) commissioner or from his heirs. The painting was described in the Amsterdam auction, item twenty-five, as "Een zittende Vrouw met meer beteekenisse, verbeeldende het Nieuwe Testament kragtig en gloejent geschildert" (A seated woman rich in meaning, representing the New Testament vigorously and glowingly painted, for fl. 400). Four hundred guilders was a substantial sum, the highest reported in the seventeenth century for a work by Vermeer. "This fact shows that when Vermeer painted in the flat classical mode that was in vogue at the time, he could produce a painting that was nearly as valuable as any sold by the most fashionable painters of the period."Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 246.

Van Swoll owned a house built on the Amsterdam Herengracht in 1668, where he lived until his death. The highly esteemed Italianate landscape painter Nicolaes Berchem (1620–1683) and probably the classicist Gérard (de) Lairesse (1641–1711), executed decorations with mythological and allegorical figures in Van Swoll's house. His collection included many Italian paintings as well as the most distinguished representatives of "modern" Dutch art. His art collection contained "singers, by Gabriel Metzu," a piece that fetched sixty-five guilders at the sale of his estate. He also owned many Italian works. It is known that he employed Nicholas Verkolje to make copies of the originals, for which Van Swoll was charged twelve guilders a copy. It is not known when he started buying art.