Vermeer's Reputation Before Le Brun's Découverte

There are several indications that Vermeer was relatively well-known during his lifetime. His name was mentioned in two contemporary travel journals and cited in relation to a dispute on Italian paintings.1 Thanks to these testimonies and the fact that he had been nominated two times as the head of St. Luke's guild of Delft, it could be said that during the artist's lifetime his was work reasonably esteemed. He had a discreet reputation in and around Delft, and he was at least known in the highest echelons of the seventeenth-century art trade outside Delft.

Vermeer's name also emerges in a few historical surveys of the time. In Dirk van Bleyswijk's Descriptions of the City of Delft (1667) he is mentioned as one of the city's artists. In the same survey a commemoratory poem by Arnold Bon on the painter Carel Fabritius describes Vermeer as Fabritius' worthy successor. Arnold Houbraken (1660–1719), the most influential early eighteenth-century writer on seventeenth-century Dutch artists, repeated what Van Bleyswijk had written, but failed to describe in greater detail the painter or his work. Houbraken also quoted Bon's poem on Fabritius but excluded the part which mentions Vermeer. According to the art historian Ben Broos, Houbraken must have known more—for example, about the existence of the relatively well-known Milkmaid—and could have written more about the painter, had he wished.2 In Broos' view the scarcity of information on the painter and the omission of his name in Bon's poem dampened the development of Vermeer's reputation in the years that followed. In the eighteenth and nineteenth century, Houbraken was followed by most, if not all, other art writers. For example, Jacob Campo Weyerman and Johan van Gool failed to even mention the name of Vermeer. In the June 1727 edition of the French periodical Mercure de France, however, Antoine-Joseph Dezallier d'Argenville cites Vermeer's name in a list of painters worthy to be included in a serious Flemish or Dutch art collection.3

Despite Houbraken's scarce attention to Vermeer and the art historical disregard that followed, there seems to have been a growing awareness and appreciation of his work among some art connoisseurs and collectors during the eighteenth century. His emerging reputation is testified by auction descriptions, beginning with the well-known Dissius Amsterdam sale of 1696 in which 21 paintings by Vermeer were sold. It is also demonstrated by enthusiastic descriptions of The Milkmaid in a series of eighteenth-century auction catalogues. Apart from a few paintings in foreign aristocratic collections, justly ascribed or not to the Delft painter, knowledge of Vermeer's art was limited to a few Dutch art dealers, collectors and connoisseurs.

It is only in 1792 that Jean-Baptiste Pierre Le Brun (1748–1813) wrote more extensively about Vermeer, although this découverte has always been eclipsed by Thoré-Bürger's (1807–1869) later rediscovery.

Le Brun and Vermeer

Galerie des peintres flamands hollandais et allemands

1792

Paris, France

Le Brun was probably the most gifted connoisseur in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century France. Trained as a painter, he took over his father's art business in 1771. He wrote in various publications about artists and artistic education, predominantly about the painters of the Écoles du Nord. During the French Revolution, he was involved in the foundation of the Muséum National. In an article, published in 1956, the French art historian Albert P. de Mirimonde concluded that Le Brun had a "[…] curious spirit and a fine eye, a taste for the rare and a feeling for the precious […] as he loved seeing and traveling, he never ceased developing these."4

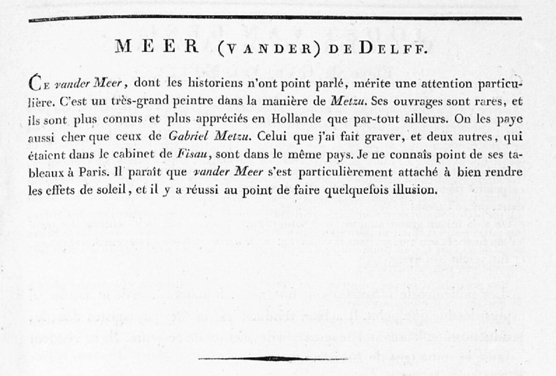

By 1792, Le Brun had traveled twenty-three times to the Low Countries.5 Through contacts with local dealers and art collectors, he acquired an incomparable knowledge of Dutch painting. At the same time he must have become acquainted with the growing appreciation of Vermeer among discerning connoisseurs and collectors. As a result, between 1792 and 1796 Le Brun published a comprehensive survey of northern school painters called Galerie des peintres flamands, hollandais et allemands (fig. 1 & 2). In the Table alphabétique he listed 1,350 Flemish, Dutch and German artists known to him at that time. He made a selection of the 157 best and most collectible painters, whom he discussed individually. From the works of these selected masters Le Brun had a total of 201 paintings engraved. The vast editorial project was published in both Paris and Amsterdam, and was partly financed by Pierre Fouquet Jr., Le Brun's principal business partner in the Netherlands.

Galerie des peintres flamands hollandais et allemands

1792

Paris, France ( list of 201 painters with engraved images, with Vermeer's name [MEER, Jean vander])

The aim of Le Brun's Galerie was to inform amateurs about Northern painters as well as to point out which of these were eligible for a good collection. Above all, he desired to vindicate the unknown masters whose names had fallen into oblivion. In Rediscoveries in Art, the English art historian Francis Haskell wrote that Le Brun was, in fact, "the first connoisseur to break with the prevailing habit of trying to attribute as many pictures as possible to the great and established names and to insist instead on the value of rarity and unfamiliarity. His whole book was designed to bring to light hitherto neglected artists such as Saenredam, and was specifically intended to replace name snobbery by snobbery of the unknown, which was to open up infinite possibilities for historians and collectors."6

Interestingly, Thoré's over-enthusiasm in reconstructing Vermeer's oeuvre seems perfectly in line with the abovementioned prevailing habit among connoisseurs that Haskell rejects.

In the Galerie, Le Brun described the Delft master for the first time in art history and praised him as artistically equal to Gabriel Metsu, who was one of the most highly esteemed Dutch painters at the time. Indisputably, Vermeer was Le Brun's greatest découverte. Or as Haskell wrote: "[…] his greatest warmth on this as on other occasions, is reserved for Vermeer."8 De Mirimonde also praised Le Brun's courage for comparing the almost unknown Vermeer to the well-respected Metsu.9

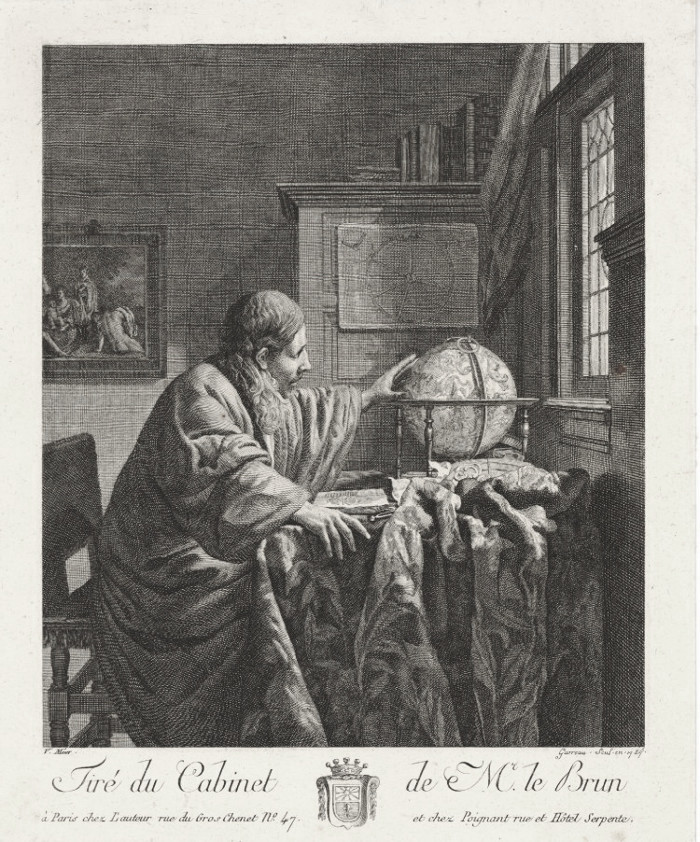

In addition, Le Brun was the first to have a work by Vermeer engraved and published. In 1784 he had Louis Garreau, a French engraver residing in Amsterdam, make an engraving of The Astronomer (fig. 3).

In Recueil de gravures au trait (1809), Le Brun published a series of simplified engravings of paintings which he said to have purchased during a journey in 1807 and 1808.11 In the Recueil he discussed Vermeer's Mistress and Maid, the second work by the artist ever to be reproduced (fig. 4). In total, two Vermeer paintings had gone through Le Brun's hands. Le Brun acquired the Mistress and Maid and A Maid Asleep, the latter of which he sold in 1811.12 Another interesting sale, which will be discussed later, regards a copy of a painting by Gabriel Metsu, in 1806. In an auction catalog entry of 1811, Le Brun described a painting by Jacob Lucasz. Ochtervelt (1634–1682) in relation to the work of Vermeer.13 For Le Brun, then, Vermeer became the point of reference, which indicates Vermeer's growing reputation in France at that time.

Johannes Vermeer

The Astronomer

1784

Engraving, 220 x 170 mm.

Receuil de Gravures au trait

1809

Paris, France

TheEffects of Le Brun's Découverte

What was the influence of Le Brun's découverte in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century?

Published both in Paris and Amsterdam, the Galerie was well known among art professionals and amateurs in France, and to some extent to those in the Netherlands and the rest of Europe as well. Auction records show that Vermeer paintings were sold with increasing frequency in the last decades of the eighteenth century.14 In most of the auction descriptions, whether the painting was correctly attributed to Vermeer or not, the Galerie was explicitly quoted. For example, on January 8, 1810, The Concert was sold for FF 131 and described thus:

Three figures in an apartment, paved with marble, busy making music. The highly esteemed works of this painter are very scarce. This one has certain, somewhat serious effect. (See what Mr. Le Brun says about this artist in his historical work about Flemish and Dutch painters).15

Gabriel Metsu

c. 1664–1666

Oil on wood panel, 52.5 x 40.2 cm.

National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

In auction descriptions Vermeer was sometimes compared to De Hooch, but more frequently to Gabriel Metsu (fig. 5), most probably owing to Le Brun's Galerie. On October 3, 1806 Le Brun auctioned his own commercial stock and part of his private collection. On this occasion, a copy of Man Writing a Letter, which is now considered one of the most Vermeer-like Metsus, was sold as a Vermeer. The sale of this painting has thus far never come to light and provides interesting information about the relationship between Le Brun, Metsu and Vermeer.

The catalogue entry reads:

"The interior of a room with a sitting young man, dressed in black, in a Spanish fashion, writing a letter on a table, covered with a Turkish carpet, placed before an open window; in the back, on the wall, a painting can be seen representing a landscape, that appears to be by van der Does. A strong and sharp lighting, a rich colour, revoking the beautiful paintings of Metsu. Some have attributed this painting to Pierre de Hogger."16

Whether Le Brun knew that he was selling a copy of a painting by Metsu as a genuine Vermeer or not, the fact that he attributed it to the Delft master is in itself meaningful, in as much as Le Brun—art critic, connoisseur, but above all businessman—must have held that an attribution to Vermeer was commercially advantageous. Most importantly, however, Le Brun's attribution and subsequent sale of the picture demonstrates that Vermeer's work enjoyed certain familiarity among French art professionals and amateurs.

Given the Galerie's distribution and eminence, it may be asked why Vermeer's newfound appreciation among the circle of art specialists did not lead directly to a greater public awareness and a definite recovery. On the one hand, Vermeer's total oeuvre is very limited and only a handful of his paintings were known at that time. Although a few works, such as The Milkmaid, were known to various dealers, collectors and connoisseurs, not until 1822 was there a single of his works on public display.17

In this regard, two important events took place in the first quarter of the nineteenth century. In 1816 Van Eynden and Van der Willigen published a history of Dutch painting, Geschiedenis der vaderlandsche schilderkunst, in which Vermeer was spoken of with great enthusiasm, confirming a certain familiarity of Vermeer among art professionals and amateurs. More importantly, in 1822 Vermeer's View of Delft was acquired for the intended national collection through the involvement of King Willem I, making it accessible to the public thereafter.

The public exhibition of the painting was picked up in 1833 by the English art dealer and writer John Smith, who, in his Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish and French Painters, wrote: "One of his best performances in this branch, representing a view of the town of Delft, at sunset, is now in the Hague Museum. This superb picture was purchased for the King of Holland […]"18

Broos suggested that rather than Thoré, King Willem I and John Smith should be considered Vermeer's true rediscoverers.19

The last act in Vermeer's recovery began with Thoré' in 1842. The French art critic must have read John Smith when he wrote: "Au musée de La Haye, un paysage superbe et très-singulier arrête tous les visiteurs […]."20 According to art historian Broos, the View of Delft sparked the French critic's interest and became the benchmark for his subsequent research.21 While Le Brun was the first to have created an interest in Vermeer among art lovers, the public display of View of Delft prompted Thoré to further investigate this great painter of whom so little was known. In the Musées de la Hollande (1858) Thoré accompanied the reader on his exploration of Dutch art paying particular attention to the "Sphinx of Delft," who seemed to intrigue him more and more by every page. The three monographic publications by Thoré on Vermeer in Gazette des beaux arts in 1866 can be considered the final act of the artist's recovery, after which followed the artist's definitive apotheosis.

What role did Le Brun's Découverte Play for Thoré's Publications?

Thoré adopted Le Brun for his argumentation and attributions in general and for his reconstruction of Vermeer's oeuvre in particular. In this respect, there are two interesting examples.

First, Thoré based his attribution of Vermeer's Mistress and Maid on Le Brun's engraving in the Recueil and praised his words: "A propos de cette peinture, Lebrun juge même assez bien l'auteur" (With regard to this painting, Le Brun makes a good estimation of its maker).22 Second, Thoré attributed the aforementioned Metsu copy Man Writing a Letter to Vermeer and seemed to base this attribution—according to the provenance he had recovered—on the Le Brun sale of 1806.23 Likely, Thoré confided in Le Brun's expertise. On the one hand, he quoted Le Brun's auctions and Recueil, and praised him for his judgment. Nonetheless, in relation to Vermeer, Thoré never mentioned Le Brun's major work, the Galerie, let alone the novelty of the découverte. It would seem that Thoré exploited Le Brun for his own argumentations, but avoided attracting attention to Le Brun' much earlier discovery. This reasoning is in line with that of art historian Frans Grijzenhout, who argues that the nineteenth-century researchers tactically exaggerated Vermeer's obscurity during the eighteenth and early nineteenth century in order to exhibit their results in a more appealing light.4

The Meaning of Le Brun's Découverte

In general, Le Brun's découverte has always been interpreted as a relatively inconsequential starting point of the appreciation of Vermeer. Le Brun was often mentioned, but has practically never been credited for Vermeer's discovery.

In the eighteenth century, there arose a growing familiarity with and appreciation of Vermeer's works among dealers, collectors and connoisseurs in the Netherlands. There, Le Brun must have learned about the Delft painter's name and fame. Being the first to write about Vermeer, he laid the foundations for a greater familiarity among art professionals and amateurs in France. However, Le Brun's discovery is of more significance.

Firstly, Le Brun explicitly focused on the discovery of unknown masters, of which he judged Vermeer to be the greatest. The concept of the découverte was central to his approach. Thus, Vermeer was anything but an accidental passage. Secondly, for the first time in art history, the painter Johannes Vermeer from Delft was mentioned, described, but also praised through a comparison with Gabriel Metsu, one of the most esteemed Dutch painters of the time. Moreover, Le Brun ordered and published the first reproduction ever of a Vermeer painting. He showed not only prescience and judiciousness, but also courage, initiative and explicitness. Le Brun effectively established a reputation for Vermeer and cleared the way for the final breakthrough.

† FOOTNOTES †

- During his visit to Vermeer in 1663, the French diplomat and traveler Balthasar de Monconys (1611–1665) was surprised by the high amount of fl. 600,- a Vermeer painting with only one single figure was sold for; the price of a Gerard Dou in those days. Furthermore, Pieter Teding van Berkhout (1643–1713) referred to the Delft master as a "célèbre peijntre."

- Broos, Ben. ‘Un Peijntre nommé Verme[e]r' In: Wheelock, Arthur K. en Ben Broos. Johannes Vermeer. New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1995: 58.

- Interestingly, Antoine-Joseph Dezallier didn't speak of Vermeer in his survey Abregé de la vie des plus fameux peintres […], which was published in 1762 in four volumes.

- Mirimonde, Albert P. de. ‘Les Opinions de M. Lebrun sur la peinture hollandaise.' Revue des Arts, nr. 6 (1956): p. 214.

- Le Brun, Jean-Baptiste Pierre. Galerie des peintres flamands, hollandais et allemands; Ouvrage enrichi de Deux Cent Une Planches gravées d'après les meilleurs Tableaux de ces Maîtres, par les plus habiles Artistes de France, de Hollande et d'Allemagne. Paris, Amsterdam 1792–1796. Volume 2: p. 79.

- Haskell, Francis, Rediscoveries in Art: Some Aspects of Taste, Fashion and Collecting in England and France. New York: Cornell University Press, 1976: p. 32.

- Le Brun, Jean-Baptiste Pierre. Paris 1792–1796. Volume 2: p. 49.

- Haskell, Francis, 1976: p. 35.

- Mirimonde, Albert P. de. 1956: p. 214.

- Admittedly, a year earlier Johannes Anton Riedel had made an engraving of Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window in Dresden, but this painting was ascribed to Govert Flinck at the time. Gaskell, Ivan. ‘Tradesmen as scholars: Interdependencies in the Study and Exchange of Art.' In: Mansfield, Elisabeth, red. Art History and its Institutions: Foundations of a Discipline. London: Routledge, 2002: p. 29.

- The supposed foreign origin did not apply to Mistress and Maid; Le Brun bought it in January 1809 and sold it in March of the following year.

- A Maid Asleep was sold by Le Brun on April 16, 1811 at an auction in Paris. Getty Provenance Index. Lot nr. 0150 from auction F-309 http://www.getty.edu/research/tools/provenance/sales_catalogs_files.html.

- Getty Provenance Index. Lot nr. 0156 from auction F-309 http://piprod.getty.edu/starweb/pi/servlet.starweb?path=pi/pi.web .

- http://piprod.getty.edu/starweb/pi/servlet.starweb?path=pi/pi.web.

- Trois personnages dans un appartement pavé de marbre, et occupés à faire de la musique. Les productions fort estimées de ce peintre amateur, sont de toute rareté. Celle-ci est d'un effet général un peu sérieux. (Voir ce que dit M. Le Brun de cet artiste, dans son ouvrage historique des peintres flamands et hollandais.)″ Getty Provenance Index. Lot nr. 059 from auction F-228. http://piprod.getty.edu/starweb/pi/servlet.starweb?path=pi/pi.web.

- Bürger, William (Théophile Thoré). ‘Van der Meer de Delft.' Gazette des Beaux Arts, (December 1866): p. 564.

- Apart from aristocratic collections like in Dresden.

- Smith, John. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish and French Painters. London 1829–1842. Volume 4, p. 110.

- Broos, Ben. 1995: p. 59.

- Bürger, William (Théophile Thoré). ‘Van der Meer de Delft.' Gazette des Beaux Arts, (October 1866): p. 298.

- Broos, Ben. ‘Un Peijntre nommé Verme[e]r' In: Wheelock, Arthur K. en Ben Broos. Johannes Vermeer. New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1995: p. 33.

- Bürger, William (Théophile Thoré). Musées de la Hollande. Amsterdam et la Haye. Études sur l'École Hollandaise. Paris 1858: p. 70.

- Bürger, William (Théophile Thoré). ‘Van der Meer de Delft.' Gazette des Beaux Arts, (December 1866): p. 564.

- Grijzenhout, Frans. ‘Een schrijfstertje van Vermeer: Jacob Oortman en de Dissius-veiling van 1696.'Oud - Holland, nr. 123 (2010): p. 66.