"Constantijn Huygens (fig. 1) is almost unknown to English readers and students—if he is known at all, it is in that peculiarly frustrating and gratifying fashion, as the father of a famous son, Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) (fig. 2), the physicist.

Christiaan Huygens, Jr.

1657

Engraving

C. de Visscher

Hollanders were better known outside their country than Constantijn Huygens. He has been a victim of his country's decline in international importance, and it is our loss not to know Huygens, for he was among whom many-faceted personalities who flash back to us the brilliance of their age…and epitomize the great period of Holland in which he lived."Rosalie L. Colie, "Some Thankfulnesse to Constantine," A Study of English Influence upon the Early Works of Constantijn Huygens (The Hague: 1956), 1.

The present study hopes to remedy a small part of this lacuna and bring one of the most outstanding personalities of the Dutch seventeenth century closer to today's readers although it is naturally impossible to do justice to every facet of Huygens' life and work. "'Indeed, whoever wishes to understand our seventeenth century must…keep his Huygens always by his hand'. This true virtuoso, 'secretary to two princes of Orange, diplomat, a polyglot man of the world, a highly sensitive connoisseur of both the ancients and moderns, a fine musician, a deeply religious man…and much more besides'"Rosalie L. Colie, "Some Thankfulnesse to Constantine," A Study of English Influence upon the Early Works of Constantijn Huygens (The Hague: 1956), 1 with note 1 Huizinga 1941. reflects in his life an entire century—Netherlands' true "Golden Age."

Caspar Netscher

1671

Oil on canvas, 30 x 24 cm.

Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague

Adriaen Thomas Key

c. 1570–1584

Oil on panel, 56 x 47 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Birth and Childhood

Huygens was born on September 4, 1596, in The Hague, Nobelstraat (near the Grote or Sint Jacobskerk), as the second son of Christiaan Huygens Senior (fig. 4) who was a personal secretary to William of Orange, Prince of Orange (1533–1584, also called "William the Silent") (fig. 3) was hailed as the Pater Patriae and first stadtholder of the young "Republic of the Seven Northern Provinces (the northern part of the former Spanish Netherlands). After William's assassination in Delft, Christiaan Huygens Senior had become one of the five secretaries to the "Raad van State" (the Council of State) demonstrating his unconditional loyalty to the House of Orange through a careful choice of his sons' names. The first-born son Maurits (b. 1595) was named after his godfather Maurits, the son and successor of William of Orange as the stadtholder. Constantijn derived his own name from the "constancy" of Breda (city in Brabant and Christiaan's hometown) for having supported the House of Orange in its struggle against the Spaniards. Christiaan declared in a letter to the Burgomasters and Councillors of Breda, that "in view of their worshipful Constancy" he wished his son "to bear the memory thereof in his name."Peter Davidson and Adriaan van der Weel, A Selection of the Poems of Sir Constantijn Huygens (1596–1684) (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1996), 9. Clearly, the Huygenses did not come from a low social standing. As Christiaan Huygens Senior jokingly phrased it: "we are born from respectable folk, are not washed to shore on a straw, or pissed down at the horse-fair." Theirs was a world of culture and civility.

(1551-7th February, 1624)

Unknown artist

c. 1580

Oil on panel

Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

Michiel van Mierevelt

c. 1629–1632

Oil on panel

Huygens Museum Hofwijck

(on loan from the Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem)

Constantijn's mother was Suzanna Hoefnagel (1561–1633) (fig. 5) who came from a family of wealthy merchants in Antwerp, and was niece of the painter Joris Hoefnagel (1542–1601). Constantijn's father came from Brabant, and although the Huygenses were not of noble birth, Christiaan's position and close relationship to the House of Orange assured his sons a successful career. Constantijn's father took extraordinary care in his sons' education in all fields, laying the ground for true and faithful servants of the House of Orange and the young Republic. The Huygens family was completed by the four daughters Elizabeth (b. 1598), Geertruyd (b. 1599), Catharina (b. 1601), and Constantia (b. 1602), among whom Elizabeth and Catharina died young, at fourteen and seventeen, respectively.

Constantijn's father devoted considerable time to his two little boys. For instance, he made a Latin grammar for them which they should read and chose the authors that should be read. For subjects beyond his expertise, he hired tutors, typically promising young men from affluent families who were still studying. "The boys received lessons in logic, rhetoric, mathematics, law, riding, fencing, dancing, and, like all Dutch children, ice skating. To guarantee them a prestigious diplomatic career, Christiaan arranged studies in modern languages, beginning with French, the language of the court and diplomacy. In sum, Constantijn had been trained from birth to be a perfect courtier.

Six years after Constantijn's first Latin lessons, at the age of eleven, he began to study Greek, which he never abandoned during his life. In the same year, Constantijn wrote his first verse in Latin, but his parents were mindful that he did not become a bookworm. Constantijn received his first lessons in Italian in 1614 from an Italian protegé of Henry Wotton, English Ambassador to The Hague, during their visit to Holland where they were neighbors of the Huygens family. Later, in his autobiography, Huygens wrote affectionately about his childhood education:

In 1599 and 1600 I started to learn reading and writing. I easily took in the material because we were always invited playfully and my father never called us with a serious expression on his face. This was the method my good father employed because he wanted to prevent in every possible way that our tender childish souls would come to hate learning.

Education and First Travels

When Constantijn was just two years old, his mother realized that her son was able to sing back to the tunes she sang so she taught him to sing a rhymed version of the Ten Commandments,The Ten Commandments are a set of ethical and moral principles in the Judeo-Christian tradition, found in the Bible. They are attributed to God's direct revelation to Moses and provide guidelines for ethical behavior. These commandments emphasize monotheism, the prohibition of idols, respect for God's name, observance of the Sabbath, honoring parents, avoiding murder, adultery, theft, false testimony, and coveting. They serve as a foundational moral code and have influenced legal and moral systems worldwide. which was in use for the congregational singing in the Calvinistic churches—the only form of music the Calvinists allowed for religious services. When he was five, his father took over the musical lessons for the boys, using the modern musical system with seven notes rather than the traditional hexachord system. Music would play a significant role throughout Constantijn's life. In the following years, Huygens became closely connected to England, not only through his personal acquaintances. Both countries excelled in a visually and technologically oriented culture, although the English contributed to it through their texts and the Dutch through their images.

In May 1616, Maurits and Constantijn were sent to the University of LeidenThe University of Leiden, founded in 1575, is one of the oldest and most prestigious universities in the Netherlands. Located in Leiden, South Holland, it is known for its academic excellence, research contributions, and notable alumni. The university offers a diverse range of programs, maintains international collaborations, and houses extensive libraries and museums. It has a rich history of scholarly and scientific achievements and is a respected institution in various academic disciplines. to study the law. Here Constantijn began his first studies in English, which would be of great benefit to him in the near future. In those times it was far from unusual that young men remained at the university for many years. Maurits left in 1617, returning to The Hague to begin his service to the State. Only one year later Constantijn finished his studies in Leiden with a Latin dissertation in law. He was sent to Zieriksee to deepen his studies in law with a prominent attorney, but with scarce enthusiasm. Fortunately, more compatible arrangements were made for him.

Father Christiaan followed the urgent suggestion of Noël de Caron, Dutch Ambassador in London, and sent Constantijn with the company of Dudley Carleton, English Ambassador to the Netherlands and a good friend, to England where he should gain knowledge of diplomatic policy and technique. Young Huygens must have been well-prepared for England, especially by Carleton, as he knew what to expect. The enthusiastic Huygens arrived with the highest expectations. As a visitor he had spare time to improve his English but at the same time to learn all he could get about the country: its literature (at first poems by Philip Sidney, a model of a "verray parfit gentil knight" who had fallen at Zutphen in the Netherlands; later, the metaphysical poet John Donne John Donne (1572-1631) was an English poet known for his metaphysical poetry, which explored themes of love, religion, and human experience. He began as a secular poet but underwent a religious conversion, becoming an Anglican priest later in life. Donne's poems are characterized by their intellectual depth, complex metaphors, and blending of the spiritual and the sensual. He is famous for works like "The Flea," "A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning," and "Holy Sonnets." Donne's influence on later poets and his profound impact on English literature make him a significant figure in literary history. (1572-1631)– to Huygens' translations of Donne see right: excursus R. Colie); its sciences (notably the famous philosopher Francis Bacon, whom Huygens met on a later journey to England) and last but not least its music and arts. Huygens, a gifted viola da gamba-player from childhood, learned to play the English viola da gamba during his visits at Henry Wotton in the Dutch Embassy, a more complicated instrument producing more varied sounds but "as sweet as an ordinary viola."To Huygens' experiences with the "Engelsche Viool'" see: Tim Crawford, "Constantijn Huygens and the Engelsche Viool," in Chelys, published by the Viola da Gamba Society of Great Britain, London, XVIII (1989), 41–60. Thanks to Noël de Caron, Huygens had the opportunity to meet King James VI, and although the King was not fond of music, Huygens delighted him so much with his most excellent viol playing that the King commanded to play again for him on subsequent evenings. Five years later (1621), on Huygens' next trip to England, James VI knighted him, as an expression of this musical enjoyment. So Huygens was thereafter entitled as "Sir Constantine," a title in which he regarded with a certain pleasure, as he put eques ("knight") on the title-pages of his later publications.

The painter Jacob de Gheyn II (c. 1585–1629), introduced Huygens to the English arts. Together they visited the picture gallery of Prince Henry (who unfortunately died young) and traveled to Cambridge and Oxford, where Huygens had the chance to meet Sir Thomas Bodley, an old friend of his father and owner of the later-to-be world-famous Bodleian Library. In his autobiography, he complained that the artist of his choice, Jacob de Gheyn II, an old family friend and neighbor, was unwilling to serve as his teacher and consequentially he was not given the opportunity to learn the art of rapidly rendering the forms and other aspects of trees, rivers, hills and the like, which northerners, as Huygens justly claims, do even better than the ancients. Huygens instead studied with Jodocus HondiusJodocus Hondius (1563–1612) was a Flemish cartographer and engraver known for his significant contributions to cartography during the late 16th and early 17th centuries. He updated and expanded Gerardus Mercator's maps, published influential atlases, and played a vital role in advancing geographic knowledge in Europe. His work remained influential for many years, and his legacy continued through his son, Henricus Hondius. (1563–1612), a print-maker whose hard and rigid lines were better suited to representing columns, marble, and immobile structures than moving things like grass and foliage, or the charm of ruins.

The English journeys were of considerable importance for Huygens: at first for his diplomatic career, but as well as for his intellectual and poetic apprenticeships. "England was the first foreign country he visited, and experience in one's first country always has a peculiar value. He observed English language and customs with an eye especially acute. More important even than this was the effect upon him of both English literature and English science. Their influence on his ideas and his work was greatest in the early part of his life."Rosalie L. Colie, "Some Thankfulnesse to Constantine," A Study of English Influence upon the Early Works of Constantijn Huygens (The Hague: 1956), 10.

But not everything went well for the young Constantijn. During his stay in England his younger sister Catharina, who had already been ill when he left, died at the age of seventeen. This was a hard blow for him, and he felt earnestly sick, but recovered gradually thanks to the care of Mr. Caron for his young guest. On November 2, 1618, he came home to The Hague, full of experience and new impressions, and ready to begin his service for the House of Orange.

Beginnings as a Diplomat and Marriage

Jan Maurits Quinkhard

c. 1738-1748

Oil on panel, 25 x 19 cm.

Amsterdam Museum, Amsterdam

From the very first, Constantijn supported his father and, with him, the House of Orange against their opponents. In 1620, he became the private secretary to François Aerssen, Lord of Sommersdyk, (an earlier neighbor of the Huygens family). Also in 1620, he traveled with Aerssen, who was now the Dutch ambassador, to Venice. During this journey, Huygens was able to take advantage of his early Italian lessons, as he was the only one in the company who could speak the language. In Venice, apart from his various duties as a private secretary, he had the chance to experience the famous culture there first-hand. He even had the opportunity to listen to the music of Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643), the great Italian Renaissance composer, which deeply impressed him as an excellent Dutch amateur musician.

In 1619, with the Hoefnagel relations of Constantijn's mother Suzanna and their Amsterdam connections, he became acquainted with Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft (1581–1647) (fig. 6), the central figure, together with Joost van den Vondel (1572–1631) (fig. 7), in Holland's literary life of that time. He also met Anna Roemers Visscher (1583–1651) and her sister Maria Tesselschade (1594–1649), both daughters of the wealthy merchant and poet Pieter Roemers Visscher (1547–1620) (author of a well-known emblem-book) and likewise poetesses of great ability. With both these ladies Huygens maintained a lifelong sincere friendship and a poetic correspondence. Together with the singer Francisca Duarte, sister of Gaspar Duarte, a highly cultivated Jewish merchant of Antwerp, they were the central figures of a fine literary and musical party, called later the "Muiderkring" (Muiden Circle) after Hooft's official residence Muiden, near Amsterdam. (For more on the Muiderkring and Huygens' relationship to the Duarte family, see Music in the Times of Vermeer, chapters 3 and 4).

Philip Koninck

1665

Oil on panel, 56 x 47 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Huygens intensely enjoyed these meetings with the literati of the young Dutch Republic, which is reflected in his own poems. Through his fluency in several languages this homo universalis was able to hold, next to his diplomatic epistolary exchange, an intensive correspondence with literary figures, theologians, philosophers, scientists and composers from all over the Continent.

Huygens read and wrote incessantly. His personal library is said to have been half the size of that of the King of France. The smaller part of his library, that in total counted approximately 8,000 books, was sold in the 1688 auction after he had died.The remainder of his library was distributed among his eldest sons and parts of it was sold in the 1695 auction soon after Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) had died and in the 1701 auction some years after the death of Constantijn Huygens Jr. (1628–1697). Huygens possessed a deep fondness for puns: they convey something of the rich and involved cleverness of his verse, the qualities which he developed from his reading of Ben Jonson and John Donne. Although his pointed and satirical shorter poems are sometimes easier to get to grips with, the extracts from longer pieces are often impressive and moving.

In 1621, Huygens became the secretary of the Dutch embassy in England and at the end of the year made his second trip there with another embassy under Aerssen. This was a further indication that he was increasingly seen as worthy of trust. During this stay in England, he met among others Francis Bacon (1561–1626) and Cornelius Drebbel (1572–1633), the Dutch inventor. Huygens had a deep admiration for both scientists and studied their works thoroughly.To investigate the influence of Bacon and Drebbel on Huygens' occupations with philosophy and the natural sciences see Svetlana Alpers, The Art of Describing (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983), chapter 1, "Constantijn Huygens and the New World" (1–25).

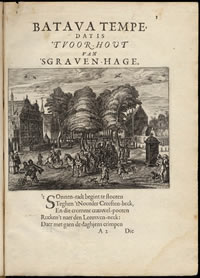

In the same year Huygens published his first large poem about the place where he grew up: Batava Tempe (fig. 8) (from the Vale of Tempe in ThessalyThe Vale of Tempe is a narrow gorge located in Thessaly, Greece, between Mount Olympus and Mount Ossa. Known for its natural beauty and historical significance, it has ties to Greek mythology and the Muses. The region is a popular tourist destination, offering opportunities for hiking, exploration, and a glimpse into ancient Greek culture. Today, it is a protected natural area with ecological importance., which in antiquity was seen as the most beautiful spot on earth)–Dat is 't Vor-hout van 's-Gravenhage. "Dat is 't Vor-hout van 's-Gravenhage" translates to "That is the Voorhout of The Hague" in English. The Voorhout is a historically significant square and park in The Hague, Netherlands, known for its impressive architecture, cultural institutions, and role as a cultural and social hub in the city. It is surrounded by stately buildings, including the Mauritshuis art museum, and has a rich history dating back to the 17th century.

Constantijn Huygens

1621

In 1614, Father Christiaan had been moved from Nobelstraat to this fine diplomat's quarter near the Royal palace of the stadtholder. His profound love of gardens (which became especially evident in his later life) is already expressed in his poem, the Hollandse Tuin ("The Dutch Garden") which deals with the wide avenues of the Voorhout (fig. 9),Lange Voorhout is a historic avenue in The Hague, Netherlands, known for its stately architecture, tree-lined promenades, and cultural significance. It was originally a tournament field in front of the Binnenhof, housing the Dutch parliament. The avenue features elegant buildings, cultural events, museums, and outdoor art exhibitions. It's a popular spot for leisurely strolls and a showcase of the city's rich history and culture. its limes and little flowers which in Huygens' eyes was perfection, a second Tempe.

Jan van Call

c. 1690

Watercolor and pen on paper, 17.6 x 27.3 cm.

Haags Gemeentearchief

On February 7, 1624, Father Christiaan Huygens died. This marked a turning point in Constantijn's life, who, although a diligent and serious-minded young man, allowed himself a certain amount of leisure. Now, together with his only one-year-elder brother Maurits, he had to bear the entire responsibility for the family. However, on February 26, Constantijn had to leave The Hague again for his third diplomatic trip to England.

Besides his current career as secretary to Prince Frederik Hendrik of Orange (1584–1647), after the death of his half-brother Maurits in 1625 the new stadtholder, Huygens dedicated himself to his own family. During Constantijn's courtship for a planned but then failed marriage of his brother Maurits with Suzanna van Baerle (b. 1599) (fig. 10),To the attribution of this painting and its history, see: Julius S. Held, "Constantijn Huygens and Suzanna van Baerle: A Hitherto Unknown Portrait," The Art Bulletin: A Quarterly Published by the College Art Association, New York, December 1991, Vol. LXXIII, no. 4, 653–668. To the musical aspect in this painting see: Frits Noske, "Two Unpaired Hands Holding a Music Sheet: A Recently Discovered Portrait of Constantijn Huygens and Suzanna van Baerle," in Tijdschrift van de Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis, XLII-1, 1992, 131–140. To the acquisition of this painting by the Mauritshuis The Hague see: Gary Schwartz, "How Sterre Came Home," Schwartzlist no. 226, accessed December 10, 2023. daughter of Jan Hendrik Baerle and Jacomina Ham, a cultivated and humanistic family, he felt in love with Suzanna and wrote many poems for her, calling her his sterre (star). Suzanna hesitated to give her consent for some time, but finally they were married on 6th April 1627.

Jacob van Campen

c. 1635. Mauritshuis, The Hague

Adriaen Hannemann

c. 1640, Mauritshuis, The Hague

Suzanna gave birth to five children: Constantijn (b. 1628), Christiaan (b. 1629, later the famous physicist), Lodewijk (b. 1631), Philips (b. 1632) and daughter Suzanna (b. 1637) (fig. 11) . For ten years Huygens lived a virtually perfect life. He enjoyed both a secure profession and a private happiness together with his beloved wife and his prospering children, although he was often away for months in order to accompany Prince Frederik Hendrik on various campaigns or "summer-camps." But Huygens felt that his felicity would not last, and he was right. On May 10, 1637, about three months after daughter Suzanna's birth ( March 13, 1637) which left the mother fatally ill, his Sterre died.

Huygens' grief was beyond all imagination. Earlier he had begun to write a poem about the happiness of his marriage, describing it as the period of one day, called Daghwerck. Huys-raed ("The Day's Work. The Order of the House"). Now he was not longer able to continue. The last part became a lament of his loss and an unrestrained loneliness and unease as is clear from the touching lines below:

Kent wat ick lijd', en troost: Mijn wederwilligh spreken

En sal den stracken draed van uw gesegh niet breken;

Tot spreken hoort noch kracht; de mijne gaet te niet:

Spreeckt, vrienden, ick besw....Maer, Leser, 'tkan bestaen, veel minder war genoegh;

Waer 'tkind volmaeckt, ten sou syn' vader niet gelijcken.(Know at last what I suffer. Console me My voice

Protesting will never cut the thread of your discourse.

Speech requires strength, all strength I had has now left me.

Speak, friends, I succ....Reader, enough, much less would be too long:

Flawed poem, child of the imperfect man.)

Ten years later, in 1638, following the encouragement of his friends, he was able to publish this memorial to Suzanna and the happiness of his married life. Since October 1627 Huygens and his family had lived in a house at Lange Voorhout (fig. 12). In March 1634, Frederik Hendrik had given Huygens a building lot at the 'Plein', close to the government's buildings in the 'Binnenhof' and near to the Mauritshuis (designed 1638 by Jacob van Campen and Pieter Post for Count Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen, nephew of Frederik Hendrik and Maurits, called de Braziliaan). Huygens began immediately to plan a stately home, according to the advice of Pieter Post and Jacob van Campen, the painter of his double portrait and one of Holland's leading architects in that time (he was also the architect of the impressive city hall of Amsterdam).