Thoré, [Etienne-Joseph-] Théophile

: 1807, La Flèche, France

:

1869, Paris, France

:

Dictionary of Art Historians

https://arthistorians.info/thoret

The "rediscovery" of Vermeer is predominantly attributed to scholar, collector, French Salon critic and co-founder of L'Alliance des arts, Etienne Joseph Théophile Thoré (1807–1869), sometimes, Thoré-Bürger, Thoré or Willem Bürger.

Thoré wrote criticism beginning in the 1830s, during the regime of the July Monarchy (1830–1848). By the 1840s his art criticism was wide ranging encompassing aesthetic and political views. He extolled the work of Eugène Delacroix, Théodore Rousseau and other Barbizon school painters, chiding the conservative painters such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres as well as the more popular artists such as Paul Delaroche and Horace Vernet. In 1842 he and Paul Lacroix (1806–1884) founded a private agency to sell and promote art, the Alliance des Arts.Also known as the Société de l'Alliance des Arts, a French association founded in 1842 with the aim of promoting a union of all the arts: architecture, sculpture, painting, music, and poetry. The idea was to encourage collaboration between these various disciplines to achieve greater artistic harmony. This aspiration to unite the arts was not unique to this society but was part of a larger 19th-century movement that sought to break down barriers between different art forms. Such interdisciplinary collaborations and movements were responses to rapid industrialization and urbanization during that period. Artists and thinkers were exploring ways to create more holistic artistic experiences that could counterbalance the fragmenting effects of modern life. The Alliance des Arts might not be as renowned today as other artistic societies from the same period, but it was indicative of broader trends and discussions happening in the artistic communities of 19th-century Europe. They also published a Bulletin. Between 1844–1848, Thoré was the art critic for Le Constitutionnel. Because of his support of some of the radicals in the 1848 revolution, (he was a Saint-Simonist and exponent of Pierre Leroux, (1797–1871) was forced into exile in 1849. He returned in 1859, continuing to write under the government of Second Empire. After living in London, Brussels, and in Switzerland, he returned in 1859, continuing to write under the government of Second Empire (1851-1870). In 1855, he began using the Dutch-sounding pseudonym "Willem Bürger," focusing his writing on northern European art. An active archival researcher and connoisseur, he is credited with the rediscovery of Johannes Vermeer and significant re-evaluations of of other seventeenth-century Dutch artists, including Frans Hals.

His criticism derided French Baroque painting as too heavily influenced by Italy, terming it as inauthentic of a national identity. He lauded Dutch seventeenth-century naturalism and what has subsequently come to be seen as the acme of Netherlandish painting, the art of the Dutch Republic. It's direct appeal to simple human virtues, he declared made it an art for the people ("l'art pour l'homme"). He continued to deplore the dark history painting of the Academie and the Second Empire, particularly that of Jean-Léon Gérôme and Alexandre Cabanel, in favor of Realism painter such as Gustave Courbet (his favorite), Jean-François Millet, and the Impressionists Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, and Auguste Renoir. As early as 1860, Thoré began purchasing Vermeer paintings. A Lady Standing at a Virginal (1672–1673), National Gallery, London) was acquired sometime before 1876, Woman with a Pearl Necklace (1664, Berlin, Gemäldegalerie) was bought from Henry Grevedon in June 1866. A Lady Seated at a Virginal (1675, National Gallery, London) was purchased for a mere two thousand francs in 1867. The sale of his collection by in 1892 brought the Vermeers and other works into more public collections.

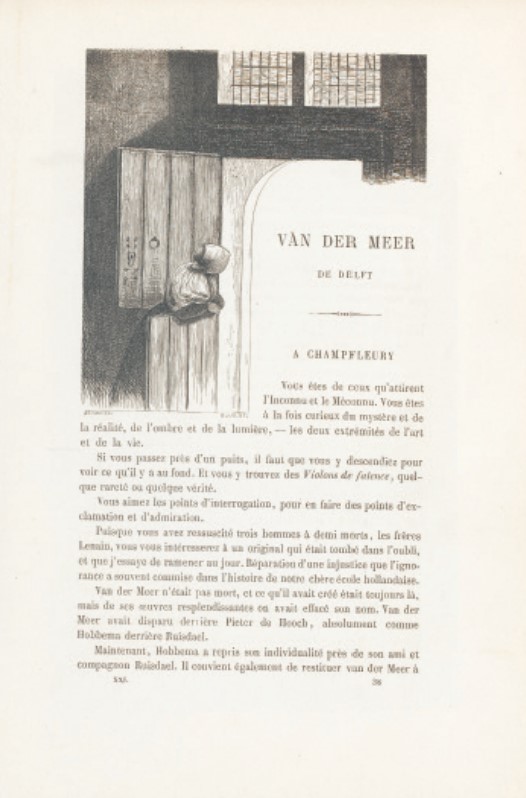

Oct. 1, Nov. 1, Dec. 1 1866 3 articles on "Van der Meer de Delft"

Noël Eugène Sotain, after Étienne Bocourt, after a painting by Jacobus Vrel, Title vignette of article by W. Bürger (Théophile Thoré), ‘Van der Meer de Delft’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts 8 (1866), p. 297 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum Research Library, S TS GAZE

Noël Eugène Sotain, after Étienne Bocourt, after a painting by Jacobus Vrel, Title vignette of article by W. Bürger (Théophile Thoré), ‘Van der Meer de Delft’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts 8 (1866), p. 297 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum Research Library, S TS GAZE  MUSEES DE AL HOLLANDE

MUSEES DE AL HOLLANDE1807–1869

Click here to read the book online.ì

John Nash

"Rediscovery," in Vermeer ( 2002)J. M. Nash, "Rediscovery," in Vermeer (London: Phaidon Press, 1991), 102–104.

Théophile Thoré, the French critic and politician, in the first major study of Vermeer, published in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts in 1866 under the pseudonym of W. Bürger. "A dozen years ago, Jan van der Meer of Delft was almost unknown in France," wrote Thoré. "His Name was missing from the biographies and histories of painting; his works were missing from the museums and private collections."

T. THORE

(W. BURGER)

1807–1869 HE WAS A MAN

SHAKSPEARE

IL FÛT UN HOMME

Thoré devoted twenty years of travel and research, in part as a political exile (hence the pseudonym), on this study of Vermeer, and in it he established not only the foundation but much of the edifice of our modern understanding of Vermeer. He begins his study with an account of his own first encounter with the View of Delft. "In the museum at the Hague, a superb and most unusual landscape captures the attention of every visitor and powerfully impresses artists and connoisseurs. It is the view of a town, with a quay, old gatehouse, buildings in a great variety of styles of architecture, garden walls, trees, and, in the foreground, a canal and a strip of land with several figures. The silver-gray sky and the tone of the water somewhat recalls Philip Koninck. The brilliance of the light, the intensity of the color, the solidity of the paint in certain parts, the effect that is both very real and nevertheless original, also have something of Rembrandt.

"When I visited the Dutch museums for the first time, around 1842, this strange painting surprised me as much as The anatomy lesson and the other remarkable Rembrandts in the Hague museum. Not knowing to whom to attribute it, I consulted the catalogue: View of the Town of Delft, beside a canal, by Jan van der Meer of Delft's . Amazing! Here is someone of whom we know nothing in France, and who deserves to be known!

"Even after seeing the Night Watch, the Syndics [by Rembrandt] and the other marvels of the Amsterdam museum, I retained an indelible memory of its masterpiece—by van der Meer of Delft! Well! In those days, we all thought of painting as something to please the eye and to write elegant descriptions for, without worrying too much about the history of art and artists.

"Later, even before 1848, having returned to Holland several times, I also had the opportunity of visiting the principal private galleries, and in that of M. Six van Hillegom—the happy owner of the celebrated portrait of his ancestor, Burgomaster Jan Six, by Rembrandt—there I found two more extraordinary paintings: a Servant pouring milk and the Façade of a Dutch house,—by Jan van der Meer of Delft! The astounding painter! But, after Rembrandt and Frans Hals, is this van der Meer, then, one of the foremost masters of the entire Dutch School? How was it that one knew nothing of an artist who equals, if he does not surpass, Pieter de Hooch and Metsu?

"Later after 1848 having become, of necessity, an exile, and, by instinct, a cosmopolitan, living in turn in England, Germany, Belgium, and Holland, I was able to explore the museums of Europe, collect traditions, read, in all languages, books on art, and attempt to untangle somewhat the still confused history of the Northern schools, especially the Dutch school, of Rembrandt and his circle and my 'sphinx's van der Meer.

"In the first volume of The Museums of Holland, in 1858, drew attention to the landscape in the Hague museum and the two pictures in the Six van Hillegom collection In 1860, in the second volume of The Museums of Holland, I authenticated more than a dozen van der Meers, and brought together a quantity of information that enabled me later to recover almost the entire oeuvre of the painter of the View of Delft. "This obsession has caused me considerable expense. To see one picture by van der Meer, I traveled hundreds of miles: to obtain a photograph of another van der Meer, I was madly extravagant. I even retraced my steps all round Germany in order to verify with conviction works dispersed between Cologne, Brunswick, Berlin, Dresden, Pommersfelden, and Vienna. But I was amply recompensed, more especially as I had the pleasure, not only of admiring the works in museums and galleries, but in acquiring more than a dozen, some that I bought for my friends MM. Pereire, Double, Cremer, and others; others that I bought for myself.

"At the same time as I was researching van der Meer's pictures, I was gathering together all the written documents and traditions concerning the man: I leafed through old books, old catalogues, the Dutch archives. vOn the biography, it is true that I have still only some chronological landmarks and a few certain facts.

Thoré knew little of Vermeer's life. He knew nothing of his marriage or even the date of his death. When he found the catalogue of the sale in Amsterdam of 16 May, 1696, at which, in addition to the View of Delft, twenty other Vermeers were listed, he surmised that the sale may have followed the recent death of the artist, or had been of the effects of another Van der Meer, of Haarlem (1656–1705), who had also been a picture dealer and had died, so he had learned, in 1691."