Our virtual exploration of Johannes Vermeer's Delft commences at the Kolk (fig. 1), the distinctive triangular harbor situated at the city's southern boundary. Here, Vermeer immortalized his magnificent View of Delft (fig. 2).

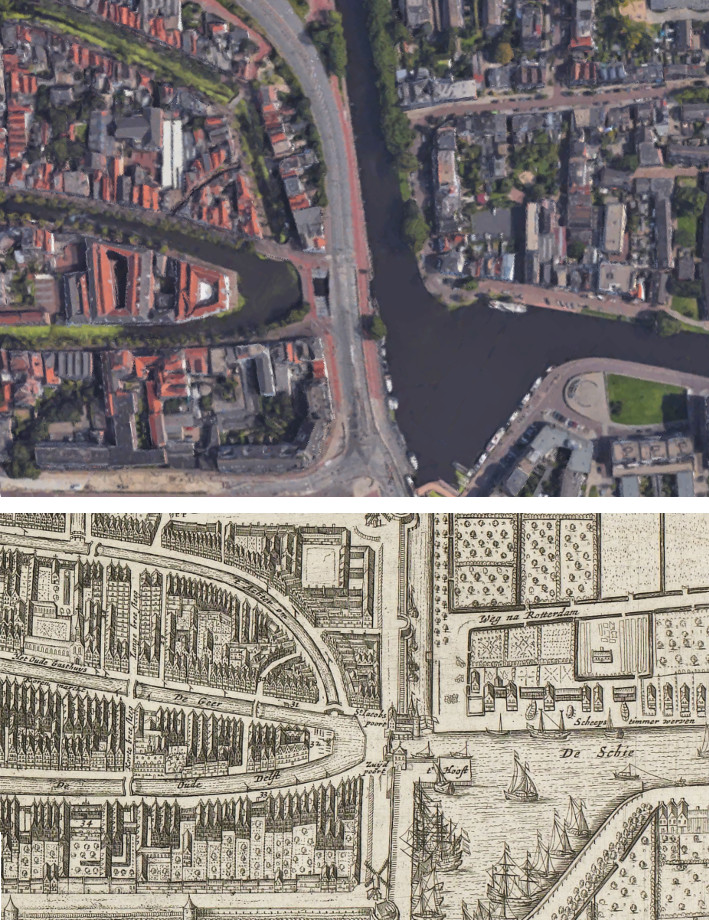

From a cartographic perspective, the geographical contours of this diminutive segment of the Dutch landscape have remained remarkably unchanged. This fidelity is evident when juxtaposing Willem Blaeu's 1648 map of Delft with a contemporary satellite image of the corresponding locale (fig. 3). Presently, the Kolk retains its original configuration and scale, and it is not uncommon to discover a vessel moored at the precise location depicted by Vermeer, where the sizeable tow barge initiated service in 1655, facilitating transport to Rotterdam. It is hypothesized that the sun-kissed rooftops in Vermeer's painting belong to a sequence of buildings along the Geer canal, immediately to the left of the prominent tower (fig. 2). The observer's gaze is invariably attracted to this illuminated segment, as well as to the radiant tower of the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church).

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1660–1663

Oil on canvas, 98.5 x 117.5 cm.

Mauritshuis , The Hague

Vermeer's warm ochre yellow sand bank in the foreground has been replaced by concrete and asphalt and a busy road now runs along the banks of the distant shore where the artist had depicted a smalschipA 17th-century Dutch smalschip was a small, narrow vessel designed for navigating the shallow, narrow waterways of the Netherlands, including canals and rivers. Typically flat-bottomed and constructed of wood, it featured a single mast with a square or gaff-rigged sail, and sometimes oars for propulsion. Smalschips were essential for local trade, transporting goods like produce, timber, and peat, as well as serving as passenger ferries and fishing vessels. Their size and design made them versatile and integral to the Dutch Republic's economy and daily life during the Golden Age, perfectly suited to the country's extensive waterway network. and a wijdtschipA wijdtschip was a broader, more spacious vessel used in the 17th-century Netherlands, primarily for transporting bulkier or heavier cargo over longer distances. Its name, translating to "wide ship," reflects its wider beam and larger cargo capacity compared to a smalschip. Wijdtschips typically had a deeper draft and were used in coastal and maritime trade, as well as on major rivers. They were equipped with a single or multiple masts, rigged for efficiency in open waters. This type of ship played a significant role in the thriving trade economy of the Dutch Golden Age, connecting inland and overseas markets. resting peacefully while a few early morning creatures stroll oblivious to their surroundings, most likely, waiting for the tow barge to leave its moorings. The clock was used by ferryboats leaving the harbor to go to Rotterdam, Schiedam, or Delfshaven. "Given the orientation of the scene, the full green foliage and the active maintenance works on these two ships which are moored at the Delft shipyard—getting ready before June 1st—it follows that the intended scene or the actual conception of this painting must be dated at an early morning in the first half of May."Kees Kaldenbach, "Tow barges, freight ships and herring buses on Vermeer's 'View of Delft'," (accessed October 29, 2023).

- For a thorough examination of the relationship between the actual historical site and Vermeer's rendering, consult: http://www.xs4all.nl/~kalden/verm/artibus-hist1982.htm

- Explore Vermeer's View of Delft with a detailed, interactive map featuring detailed rollover functionality.

The Kolk

The Kolk, formally known as Zuidkolk, is a sizable, triangular harbor situated on the southern flank of Delft, encompassing three city gates that are discernible in Vermeer's painting. Integral to the Schiedam watercourse, which joins the Maas River, the Kolk lies mere kilometers from the bracing waters of the North Sea. This pivotal locale served as a confluence from which thoroughfares and waterways fanned out to Rotterdam, Schiedam, and Delfshaven.

Originally, Vermeer's depiction of Delft's distinctive skyline was rendered with stark clarity, the water portrayed as a glassy expanse, unbroken by any hint of movement. Subsequently, Vermeer altered the canvas, imparting a subtle disturbance upon the water's surface to suggest the caress of a zephyr. The reflections of the Rotterdam and Schiedam Gates were extended, seamlessly binding the skyline to the quayside.

The genesis of the Kolk's unique geometry can be traced back to a bastion erected in 1573 amidst the modernization of the city's defenses. By 1614, efforts were undertaken to excavate the Kolk, resulting in the establishment of a more utilitarian harbor. At the time, it was considered too shallow and too small: insufficient for docking ships. The construction was terminated in 1620.

In 1655, the construction of the Schie Canal was realized, complete with a towpath on its western periphery. This development, orchestrated by the Delft city council, was designed to boost commerce from Delft to Delfshaven. The trekschiuten, or tow-boat ferry service, commenced from the Zuidkolk, in proximity to the Kethel or Schiedam gate, offering hourly departures and facilitating connections to Overschie, near the Maas River. This service provided a direct route to Delfshaven and branching paths to Rotterdam and Schiedam. With a schedule of thirteen to fifteen daily services to Rotterdam, excluding Sundays, Delft emerged as a strategic node in the transport network of Southern Holland. The endeavor required intricate negotiations with a host of landowners and the creation of essential infrastructures such as bridges and toll exemptions, coupled with the establishment of right-of-way agreements. Once completed, the Kolk was the main point of departure to other cities and to other countries via the Schie and Maas. One could access Rotterdam, Schiedam, and Delfshaven as well as the Flanders and Brabant, France, England and thereon to every corner of the world.

Other than the triangular form of the waterway, little remains of the Kolk in Vermeer's View of Delft. Both of the gates and the town wall were pulled down in the 1830s. Most of the stepped-gables in the painting have been replaced by modern facades. In Vermeer's representation, only the towers of the Nieuwe Kerk and the Oude Kerk (Old Kerk) have survived even though the present stone spire of the Nieuwe Kerk dates from 1875. The original wooden spire caught fire when it was struck by lightning three years earlier.Michel van Maarseveen, Vermeer of Delft: His Life and Times (Amersfoot and Brugges: Bekking & Blitz, 2001).

Presently, the Kolk serves as a harbor for various moored vessels and facilitates the passage of both small and large watercraft. It constitutes a section of the Rijn-Schiekanaal, providing a navigable route between the cities of Leiden, Delft, and ultimately Rotterdam. The canal is pivotal for a range of activities, particularly commerce, with numerous commercial vessels transporting essential goods for trade. Additionally, it is a destination for recreational boating, where private vessels traverse the picturesque waterway for pleasure and tourism.

The Kolk in Vermeer's View of Delft

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1660–1663

Oil on canvas, 98.5 x 117.5 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

Vermeer's View of Delft represents the city of Delft as seen from the south. Beyond the harbor lies the deep brown city walls which are broken only by the small Kethel Gate and the larger Schiedam Gate with its clock tower. The Rotterdam Gate is recognizable for its twin tower. None of these architectural features has survived. It should be noted that Vermeer chose a rather uncharacteristic profile of Delft for his painting.Kees Kaldenbach, "The Genesis of Johannes Vermeer and the Delft School a Wall Chart on the Cultural Heritage of Seventeenth Century-Delft," (accessed October 29, 2023). In the harbor are several horse-drawn barges and a few freight ships, and at the right near the shipyard two herring busses under repair. In the gently rippling water we see the elongated reflection of the city wall and the buildings on the quay, with the Schiedamse poort (Schiedam Gate) on the left and the Rotterdamse poort (Rotterdam Gate) with its twin towers on the far right. It is striking that Vermeer did not depict the entrance to the city in bright daylight, as every other painter depicting a comparable setting had done up to that time. The two gates, with the small bridge, the Kapelsbrug, in the middle, the city wall with the salmon-colored roofs of the arsenal and the towers of the Oude Kerk and De Papegaey (the parrot) brewery on the left, lie in the shadow of one of the clouds drifting over. Vermeer illuminated the scene from the right and placed the city center with the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk in the background in dazzlingly bright light.Pieter Roelofs,"Venturing into Town," in VERMEER, ed. Pieter Roelofs & Gregor Weber, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2023, 142. Traditional cityscapes of Delft generally emphasized its most distinctive landmarks. The Oude Kerk, one of the most venerable monument of all, rendered in muted gray tones that can barely be discerned in the distant left center of the composition (fig. 4).

The photograph above (fig. 5) was taken from a position very near to the point where Vermeer painted his picture, more or less at the same height from the ground. Historians believe that the artist worked from the second story of an inn that has been long since torn down. The perfect peacefulness which reigns over the scene no longer remains unless one seeks to find it within. But we should remember that the peacefulness of Vermeer's picture was probably the painterly artifice rather than historical fact given that this part of Delft was one of the city's busiest.

With a little luck and the right timing (the time is indicated by the clock of the Schiedam gate about 7:15 to 7:30 A. M.) the typical low flying cumulous clouds and cool Dutch light inevitably suggests something of the atmosphere of Vermeer's sublime masterpiece. To be sure, the shoreline is still in the right place, the spire of the Nieuwe Kerk still can be seen and a tiny sliver of the bizarre tower of the Oude Kerk peers over the clean modern skyline.

But even if the expanse of Dutch sky is there and the two key monuments tell us we are aligned correctly, and even if we are able to ignore the differences in architectural design and construction materials and remember the red masonry and deep green vegitation of Vermeer's picture, that today's viewer generally walks away from the Plein Delftzicht with the sensation that something is jarringly different from the setting in Vermeer's time. The background shore is distant, much farther away than in Vermeer's painting.

Precisely at this juncture, one is assailed by the doubt that the painter took great liberties in his interpretation and that his poetic vision is rooted in something else than a literal transcription of a long lost world. "As usual, Vermeer created a reality whose bits and pieces can be disputed in terms of factual accuracy but whose artistic "rightness" is overwhelming."Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2001), 110.

Although Vermeer's View of Delft depicts a gleaming, clean city, the reality for the painter and his peers was likely quite different due to the numerous potteries, distilleries, breweries, and soap-rendering plants that would have produced constant clouds of smoke. Fires for cooking and smoking products meant that they would have been a perpetual presence in the city center where people lived and worked. Additionally, Delft's lack of a sewerage system and the existence of a central burial ground created a terrible stench. The city had measures in place, like a fifteenth-century recycling station called de Stille Putten for waste processing and strict waste disposal regulations enforced by city governors. Waste was collected and sold for profit, suggesting an early form of recycling. Despite these efforts, the city struggled with odor problems, leading to continuous revisions of waste management laws, indicating that residents often flouted these rules."Ingrid van der Vlis et al., "In the Footstep of Vermeer," in Vermeer's Delft, edited by David de Haan, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Babs van Eijk, and Ingrid van der Vlis (Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, Museum Prinsenhof Delft, 2023), 129-133.

MICROSOFT'S Search Maps

Comparative portrayals John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989).

For credible comparisons, we must rely on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century drawings and topographical maps, none of which is perfectly accurate. These comparisons reveal that in the course of execution, Vermeer moved toward greater compositional simplicity, at the expense of literal realism. Vermeer seems to have played down the three-dimensionality of the site, emphasizing, instead, its overall frontality. A comparison of Vermeer's painting with topographic views taken from more or less the same angle, such as the one drawn by Abraham Rademaker (1677–1735) in the early eighteenth century, indicates that Vermeer made the houses in the foreground of the city more uniform in size and less closely packed than they were in reality. He apparently introduced these changes to achieve a more isokephalism, frieze-like effect; in the manner of a classical theorem (except that he was portraying houses rather than people lined up in a row as in a Roman bas-relief). He also reduced the size of the figures on the shore in the foreground so as not to distract the viewer's eye from the structures beyond the river. Except to a viewer who was extremely familiar with the site, the alterations he introduced must have enhanced the illusion of reality. Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627–1678), Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. points out, does not recommend that paintings copy nature but that they give the appearance of having copied nature. And if Vermeer used an optical device such as a camera obscura, it was not so that he could get the view of Delft "just right," but to create special effects, to enhance the sensation of reality by stressing contrasts of light and dark, and to help him render his colors more vivid.

Compare Vermeer's rendering with other artworks of the same scene. Click on image to enlarge.

View of Delft (detail)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1660–1663

Oil on canvas, 98.5 x 117.5 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

A View of Delft (detail)

Gerrit Toorenburg

c. 1750

Teylers Museum, Haarlem

Abraham Rademaker

1700–1710

Drawing and wash, 66 x 106 cm.

Stedelijk Museum Het Prinsenhof, Delft

Jan de Bisschop

c. 1650–1660

Graphite, pen and brush amd brown ink

9.5 x 15.5 cm.

Amsterdams Historisch Museum, Asmterdam

Jan van Kessel

c. 1649–1669

Black chalk, pen and brown ink, 17.9 x 24.4 cm.

Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels, De Grez Collection