Vermeer and the Musical Instruments

"In the seventeenth century as now, music was an integral part of Dutch culture at all levels of society. In sophisticated circles, intimate musical gatherings were not only a pleasurable means for escaping everyday cares, but a popular and widely accepted vehicle for facilitating social contacts, particularly with members of the opposite sex. Indeed, many seventeenth-century songbooks published for domestic use were exclusively devoted to amorous love songs."Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Gerard ter Borch (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2005), 174. Music played a significant role in the daily life of the Netherlands in spite of the restrictions from the Calvinist church. Wealthy burghers loved to display their newly gained life-style in elegant musical companies in which expensive musical instruments played an important part. But the love of music was common to the lower classes as well.

Numerous paintings by Jan Steen teach us much about the contemporary folk instruments used by the lower classes, like the fiddle, the hurdy-gurdy, the "rommelpot" or the "bombas." These instruments, however, do not appear in the compositions by Vermeer. Instead, he depicted instruments in vogue among the upper class: the virginals, the viola da gamba, the lute and above all, the cittern. Musicologist James Melo writes: "It has been remarked that Vermeer painted the very essence of stillness and silence…Compared with the lively and busy atmosphere of paintings appropriately entitled merry company or a musical gathering, Vermeer's rendering of musical instruments is almost clinical and detached at first sight…It is, however, significant that he never painted musical scenes that could be related to the lower classes in the social scale of the time. One looks in vain in his paintings for the boisterous drunkards and peasants that populate the genre paintings of several of his contemporaries."James Melo, "From Boisterous Noise to Inner Silence: The Depiction of Musical Instruments in Vermeer's Paintings," in Music in Art XXVI/1-2 (2001): 148.

In thirteen of the thirty-six known Vermeer paintings, a remarkable variety of musical instruments are portrayed even though they are not always clearly visible and in some cases they appear as a symbolic prop. But nonetheless, their frequency suggests that they held significant interest for the painter.

In Vermeer's paintings we find four muselar virginals, one harpsichord, three bass viols, five citterns, two lutes, a guitar, a trumpet and a recorder. In eight or nine compositions, music-making is the central theme. We do not know whether Vermeer himself kept any musical instruments in his household. Not a single one was listed in the inventory of 1676. However, it is very likely that Vermeer's patrician mother-in-law, Maria Thins, had at least one instrument, perhaps a lute, and that he often had the chance to observe them first-hand at the home of his patron Pieter van Ruijven. In Van Ruijven's inventory, a viola da gamba, a violin and two flutes, together with several music books were mentioned.Edwin Buijsen, "'Music in the Time of Vermeer," in Dutch Society in the Age of Vermeer, edited by M. C. van der Sman (Zwolle: Waanders, 1996), 115. Vermeer may also have had direct access to them at the home of the wealthy Delft brewer Cornelis Graswinckel whose remarkable collection of music books contained a large part of vocal music, several editions for keyboard instruments and tablatures for flutes.Frits Noske, Music Bridging Divided Religions. The Motet in the Seventeenth-Century Dutch Republic, Vol. I (Wilhelmshaven: Florian Noetzel Verlag, 1989), 22–23. Many critics have speculated on Vermeer's ties with Constantijn Huygens who is considered one of the foremost figures of Dutch culture. Huygens was an accomplished musician, composer and art connoisseur and if indeed Vermeer did know him, he would have certainly taken the hour's walk to the nearby Hague to admire his important collection of musical instruments.

Most of the instruments that Vermeer portrayed in his paintings are well known in our time, thanks to the increasing interest in the early music. But what do we really know about the different models of lutes or the history and technique of the cittern, the viola da gamba, or the trumpet? This study attempts to shed some light on the history of the musical instruments in general and on Vermeer's instruments in particular.Information to the virginals is to be found in the study Vermeer and the virginals and is not treated here. The same goes with the harpsichord, a keyboard instrument similar to the virginals. The harpsichord generates sound in the same manner by plucking the strings with a jack, but it has a triangular shape and consequentially, there are differences in the number, length and arrangement of its strings.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 51.4 x 45.7 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Love Letter (detail)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1667–1670

Oil on canvas, 44 x 38.5.cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1675

Oil on canvas, 51.5 x 45.5 cm.

National Gallery, London

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 73.3 x 64.5 cm.

The Royal Collection, The Windsor Castle

Johannes Vermeer\

c. 1662–1668

Oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Girl with a Flute (detail)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1665–1670

Oil on panel, 20 x 17.8 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1663–1666

Oil on canvas, 72.5 x 64.7 cm.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston<

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1673

Oil on canvas, 53 x 46.3 cm.

Iveagh Bequest, London

How Accurate are Vermeer's Paintings of Musical Instruments?

In a recent interview, an early Dutch music expert points out that the instruments "are accurate but they could be more accurate." Albert-Pomme de Mirimonde ("Les Sujets musicaux chez Vermeer de Delft") wrote that the musical annotation on the crumpled sheet of paper lying on the foreground chair in Love Letter does not make musical sense. Moreover, the structure of the flute in the Girl with a Flute does not seem entirely convincing, a fact, together with other anomalies in the work, have brought many Dutch painting experts to doubt the painting's authenticity. In other cases, such as the virginal in The Music Lesson, seems to have been rendered with near mthamatical precision. All in all, despite their occasional and relatively minor inccuracies, the musical instruments in Vermeer's paintings seem to be coherent with his overall system of representation.

Early Sources: Classification Systems

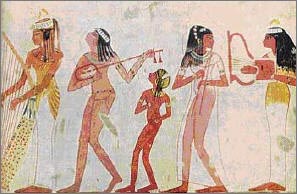

The first musical instrument was, of course, the human body with its capability of generating vocal or percussive sounds (singing, whistling, clapping hands). Stones served as early percussion instruments, most likely for the purpose of sending signals rather than for enjoyment. The first hand-made instrument was undoubtedly a bone flute. One was found in a cave and was made about 45,000 to 50,000 years ago by the Neanderthal man. Several instruments are mentioned in the Bible (e.g. the harp, the cythara, the trumpet), and one of the oldest depictions of musical instruments comes from the ancient Egyptian culture. Thus, musical instruments have always been an important companion to all cultures and races.

The evolution of crafts and the institution of corporative guilds in the Middle Age spurned further development and refinement of the various kinds of musical instruments. Demand by European courts increased enormously.

Old Egyptian mural painting.

Thebes, Dieserkere-Seneb's Tomb.

Once music had been established as a science (later the "musicology") in the Baroque period, it became necessary to classify all existing instruments. One of the first to provide an extensive overview of the contemporary musical instruments and their practice was the German composer and organist Michael Praetorius (1571–1621). His Syntagma musicum (Wolfenbüttel 1614–1620) in three volumes deals firstly with religious music, its principles and its liturgical contents (tomus primus: Musicae artis analecta 1614–1615). Then, detailed information follows about the instruments themselves (tomus secundus: De organographia, with the pictorial supplement Theatrum instrumentorum, 1618–1619) and lastly a dictionary dealing with contemporary musical forms. The dictionary also provides detailed considerations of purely technical aspects of music such as notation, proportions, solmization, transposition and polychoral writing (tomus tertius: Termini musici, 1618–1619). The importance of Syntagma musicum lies less in its influence on the succeeding generation of composers than in its documentary value. It reflects the extraordinary spread of instrumentation, numerous families of instruments and performance in the early Baroque period.

One of the central figures in the seventeenth century for science and music was the French mathematician, philosopher and music theorist Marin Mersenne (1588–1648). His works combine Renaissance and Baroque ideas summing up the accomplishments of the past. It poses difficult questions for the future inherent in new attitudes of his own time. In his most important work, Harmonie universelle (Paris 1936/37), Mersenne developed both theoretical and practical ideas regarding music and even shows concern about techniques for teaching of children and beginners. His classification of musical instruments (partly indebted to Praetorius) and his extensive presentation of the structures and capabilities of both occidental and oriental instruments then known to him are of great importance to the organology.

The Co-operation of Musicology and the Art of Painting

from: "Conclusions and Perspectives"Certainly, here is the footnote formatted in Chicago Manual of Style: 1. "Conclusions and Perspectives," in The Hoogsteder Exhibition of Music & Painting in the Golden Age, edited by Edwin Buijsen and Louis Peter Grijp (Zwolle: Waanders Publishers, 1994).

There are two ways of looking at a painting with musical elements: as a work of art, or as a document on the practice of music; through the spectacles of an art historian or a musicologist. In the most favourable situation these two co-operate, that is, they use each other's knowledge and insight. For example, the art historian can ask the musicologist the names of the instruments in a painting, whether they are accurately portrayed and whether the context is meaningful—all this in order to establish the degree of realism and symbolism in a painting. And in the turn the musicologist, perhaps studying the history of an instrument, may ask the art historian to date a painting and suggest where it was made, together with the conventions attached to the images used and symbolic interpretations that will help to understand correctly the information given in the painting.

Dutch painting of the seventeenth century is thoroughly studied by those who investigate the history of instrument making. Thanks to the realism with which these paintings are done it is often possible to deduce facts about the instruments that do not become clear from examining those that we have inherited. Many instruments in museums today have undergone changes and adaptations over the years so that it is scarcely possible to discover what they were originally like. Often the range of pitch has been altered—usually expanded. Harpsichords are given more keys, lutes more strings and a longer neck, woodwinds more keys. When we look at these paintings we appear to see the instruments in their original state.

The first universally accepted classification of musical instruments was devised by Victor-Charles Mahillon, curator of the instrument museum of the Brussels Conservatory. He compiled a catalogue of the collection which began to appear in 1880. It became the basis of later systems, such as that of the Austrian ethnomusicologist Erich Moritz von Hornbostel (1877–1935) and the German musicologist Curt Sachs (1881–1959). Their new system, first published 1914 as Systematik der Musikinstrumente: ein Versuch, became famous world wide. It was called the "Hornbostel-Sachs-system" and was the most significant work in the last two hundred years and the foundation of the modern organology (in German: "Instrumentenkunde"). The system, which has been continually developed and readapted, divides instruments into four main groups according to the manner in which they generate sound.

- Idiophones, which produce sound by vibrating themselves (e.g. the xylophone);

- membranophones, which produce sound by vibrating a membrane (like the drums);

- chordophones, which produce sound by vibrating strings (the viols or the lute);

- aerophones, which produce sound by vibrating columns of air. (the organ or the flute).