Louis Peter Grijp (1954) studied the lute at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague and musicology at Utrecht University. In 1975, still a student, he joined Camerata Trajectina, which was founded a few months before. Together with Jan Nuchelmans he organized several early music events in Utrecht, which eventually led to the foundation of the Utrecht Early Music Festival. Grijp wrote a dissertation on Dutch songs (Utrecht University 1991) and became a specialist of early Dutch music. Now he is special researcher at the Meertens Institute of Dutch Language and Culture in Amsterdam and Professor of Dutch Song Culture at Utrecht University. He wrote many articles and was co-author of books a.o. Music and Painting in the Golden Age (Hoogsteder Exhibition 1994), in which he developed ideas which came back in several CD productions about painting: The Musical World of Jan Steen (1996) in cooperation with the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and Pickelherring. Music around Frans Hals (2004) with the Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem. Grijp was editor-in-chief of A Music History of the Netherlands (2001). As artistic leader of Camerata Trajectina he has created dozens of programs on all kinds of themes from Dutch history, literature and art. Besides the lute he also plays the diatonic cittern.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 73.3 x 64.5 cm.

The Royal Collection, The Windsor Castle

April 11, 2005

The Essential Vermeer: In the seventeenth century, Dutch painting reached one of the high points of Western art and a level of technical sophistication which has perhaps never been rivaled. Three painters of absolute genius, Frans Hals, Rembrandt van Rijn and Johannes Vermeer were born within less than 50 kilometers of each other and died only ten years apart. How might we compare the state of Dutch music in the same period? What are the most noticeable parallels and divergences between the musical and pictorial cultures of the time?

Louis Peter Grijp: As you say, in the Dutch Golden Age painting reached world level. Literature from this period is seen as a high point in national cultural history but music really had a decline. That had to do with political and religious developments. The northern Netherlands became independent from Spain and thus "lost" the court in Brussels. The stadtholders Nassau did not have the power and means to develop a rich court culture comparable with other European courts like France or England. They don't seem to have been very musical either. So there were no court ensembles in Holland until the eighteenth century. In the 1570s most cities converted to Calvinism, thus losing the rich musical culture of the Catholics. Instead of professional church choirs the Calvinists accepted only congregational singing and they even prohibited organ playing. Thus the two classical forms of musical patronage, court and church, disappeared. Only the cities had organ and carillon players in their service. So the possibilities for professional musicians were limited. Yes, they could play in weddings or parties, or become teachers. But the conditions for a splendid musical life were absent. Paradoxically, under these conditions one of the finest Dutch composers of all times worked in Amsterdam: Jan Pietersz Sweelinck. One could say: many people could afford paintings as well as musical instruments - to play on themselves, as amateurs. But nobody was rich enough to maintain an orchestra or professional choir—or wanted to spend his money on it.

What place did Dutch music occupy within the context of European musical culture?

Most music the Dutch played was from abroad. Popular song tunes came from France and England, and were sung with Dutch words. Even the psalms they sang in church were composed in France. Serious music, to be played and sung in collegia musica (amateur ensembles of wealthy burgers) was mainly Italian madrigals, Latin motets, French polyphonic chansons and just a few Dutch compositions.

A veritable army of Dutch painters worked from dawn till dusk to satisfy the voracious appetite of the local art market and for the first time paintings had become wares. Some Dutch painters were in demand abroad working for foreign connoisseurs and aristocracy. A number of Dutch painters had traveled to Italy to absorb the lessons of the great Italian masters and some returned home to spread the revolutionary realism of Caravaggio. What considerations might we make concerning the economics of Dutch music and about musicians' contacts with their colleagues outside of the Netherlands?

In some way or another the wealthy Republic did attract musicians from abroad, like the lutenist Nicolas Vallet, who founded a dance school in Amsterdam in cooperation with English musicians.

Those Dutch artists which are generally esteemed today received their training through a tried-and-proven master/apprentice relationship. This relationship was regulated by local Guilds of Saint Luke which also governed the commerce of their members and protected them from outside competition and most likely ensured the exceptionally high level technical of competency for which Dutch painting is renowned. Did there exist any analogous system of training and/or trade regulation among musicians? If not, how did musicians receive their training?

In a way, yes. We know of musicians accepting pupils, who lived with them and when they had made progress, they could play together at weddings and parties. Organ players had pupils; Sweelinck, for example, had many German pupils, even living in his house. These pupils hoped to become professional players. In Leiden, university students took lessons from various teachers, including Joachim van den Hove, who also had students in his house.

Netherlandish iconoclasts stripped Dutch churches of the art which had embellished them for years. It was held that the proper vehicle for transmitting the message of God was the Word and that visual images were fit only to inspire baser feelings, for which the churchgoer had no need. What was the prevalent attitude of the Dutch Protestant churches toward religious and secular music?

Psalms, psalms, psalms. No polyphony, no organ. This became a musical disaster, because the churchgoers could not sing all these different, difficult melodies. So after a long 'organ struggle' the organ came back to accompany the singing congregation. Before that, the organ could only be played before or after service, or just as public concerts.

In the Netherlands, who were the most popular musicians and esteemed composers of the decades when Vermeer was active? Are they also appreciated today to the same degree?

What I described is mostly about the first half of the seventeenth century. In Vermeer's time Baroque music was becoming more popular in Holland. On the other hand, much music was still rather old-fashioned, like the music by Anthony van Noordt, an organist in Amsterdam who published his Tablature Book in 1659. But what is actually more relevant for the understanding of Vermeer's paintings are harpsichord manuscripts like that of Anna van Maria Eyl, who received the book in Arnhem in 1671, when she was 15 years old. It was compiled by her teacher, Gisbert van Steenwick, who notated several pieces of his own hand and a lot of settings of songs and dances like Petite Bergere, Bel Iris, De May, Almains, Sarabands etc. This is the kind of music that must have sounded in Vermeer's interiors.

It has been calculated than less that 5% of the entire artistic production of the Dutch artist have survived. Have we been luckier with written forms of music and instruments produced in the same period?

I suppose less lucky with written music. Of the hundreds of harpsichord manuscripts that must have existed only a handful have been preserved, and even fewer manuscripts for the lute, cittern, viol or the carillon. In the case of instruments, it depends. I believe not one single Dutch harpsichord has survived, but a lot of Flemish have (Ruckers, Dulcken). And these were played in Holland, too. Dutch lutes and citterns from the seventeenth century are very rare now. The only citterns we are sure of that they are of certain Dutch origin were excavated from the mud of the Zuyderzee! But we still have shawms and recorders, made by famous Amsterdam makers like Haka, and also violins and viols.

To some degree or another, the cultural distance which separates us from the seventeenth century prevents us from fully understanding the meaning of Dutch art. Thanks to the efforts of Eddy de Jongh, Dutch painting, which had been originally understood as a straightforward portrayal of contemporary life, has been reexamined for its "hidden" symbolic meaning and supposed didactic content. On the other hand, Svetlana Alpers has drawn attention to the fact that the main motivation for Dutch realism is curiosity about the world which is accessible through sight and expressed in visual terms. Can you tell us something of the technical and philosophical problems encountered our interpretation of Dutch music of those times?

What is to some extent comparable with the symbolism in art is word painting in music, madrigalisms as well as baroque rhetorica. Certain musical figures can have a meaning, especially in combination with the text. Obvious are high notes for words meaning "high" or "mountain" or "heaven" and low notes for "deep" etc. But it is often more ingenious and emotional. Constantijn Huygens for instance (who composed a lot of music himself) uses repeated notes when singing "I am standing," or makes a long rest after "death" or "silence." Very effective. As in paintings one can discuss about these figures, how to interpret them or if they should be interpreted at all. Some composers seem to use them, others not. In popular song they are virtually absent.

Let's talk about Vermeer for a moment. Many of the objects in Vermeer's canvases are so accurately portrayed that they can be identified with existing models. Through a few carefully placed dabs and dots of paint, James Welu was able not only to identify the book which lies on the table* in the "Astronomer," but even the exact edition. How accurately were the various musical instruments portrayed in Vermeer's compositions? Have you noted any discrepancies worth pointing out?

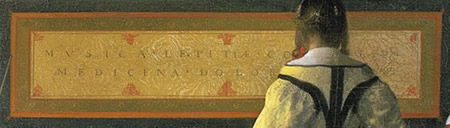

They are accurate, but they could be more accurate. Long ago I did research on cittern frets and compared the patterns of existing instruments and technical engravings with paintings. Jan Miense Molenaer and Cesar van Everdingen were my heroes, one could copy their fret patterns on real instruments. Vermeer just painted stripes on the cittern of The Love Letter, you cannot take it literally. But on the other hand the form of the instruments is very well done, e.g. the perspective of the viol on the floor in The Music Lesson in the possession of the Queen of England, or the cittern on the chair in the Drinking Lady in Berlin.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 51.4 x 45.7 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1667–1670

Oil on canvas, 44 x 38.5.cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1673

Oil on canvas, 53 x 46.3 cm.

Iveagh Bequest, London

Could you tell us something of the differences between the three different stringed instruments, the lute, cittern and the Baroque guitar, which appear in Vermeer's compositions ?

The lute is the most 'perfect' of these plucked instruments, with its six courses (that is five double strings and one single), or sometimes a few courses more (g'-d'-a-f-c-G, F, E, D, C). One can even play learned polyphonic music with different melodic lines at the same time, or when this becomes too complicated, one can suggest at least the polyphony. The cittern with its odd tuning (e'-d'-g-a) is much more limited: one can best play in G major or minor and even in these favorite keys one has to cope with the limitations of the diatonic frets. No polyphony, more emphasis on rhythm. An important difference between lute and cittern is the material of the strings: the gut strings of the lute sound rather soft and warm. The brass strings of the cittern sound much louder, also because they are played with a plectrum, whereas the lute is plucked by the bare fingers, without using the nails. A good cittern sounds a bit like the virginal. The guitar is something special. In Vermeer's time it had five courses, without much bass. It had gut strings and was played by the fingers, so the sound was comparable with the lute, although the construction of the sound box with upright sides makes it different. The lute has a round back, constructed with ribs; this gives another kind of sound projection. The most conspicuous characteristic of the baroque guitar is its playing technique, which is a combination of melodic fingers playing and so-called rasgueado's, the typical Spanish strumming of chords in a variety of ways. But it is still a delicate instrument, not as loud as the present flamenco guitar. So Vermeer's plucked instruments are different shades of delicacy.

It seems very likely that through his Delft patron Pieter van Ruijven, Vermeer had access to one of the most discerning connoisseurs of his time, Constantijn Huygens, himself an accomplished poet, musician and composer. Judging by the evidence in Vermeer's paintings, is it possible to make any judgment about Vermeer's own level of musical culture?

In general I suppose painters knew very well what they were depicting what they were depicting in terms of the way instruments are held when playing or the combination of instruments. That is true for Vermeer too, the music making of the women he painted seems very natural, and the rare combinations are fine, like the Trio once in Boston: singing, harpsichord and lute.

Do you think that the choice of instrument had any bearing on the symbolic content of the painting?

Maybe sometimes an amorous atmosphere is enhanced by the music, for instance by the cittern in The Love Letter. But I don't think one can interpret music so emblematically as in the paintings of e.g. Molenaer and others.

In Vermeer's Love Letter, a crumpled piece of sheet music appears on the foreground chair, it is painted accurately enough to make out at least part of the musical notation. Have you ever examined this case closely? Does it make any musical sense?

I can't remember this case exactly. Usually such paintings give you the feeling that you can read the music, but vaguely. Sometimes one is convinced that the painter must have used a real sheet of music as a model, and that if one had that sheet at hand, one would be able to recognize it. Unfortunately it is practically impossible to find the music and identify such pieces, unless the painter had the intention to make it recognizable. For instance, in the famous painting of Hendrick van Vliet in Delft one can read the title of the piece, or in the Family portrait by Abraham van den Tempel in Amsterdam. I once was lucky and recognized two pages of a song book of Bredero in a painting by Gerard Dou, who did not intend it to be recognizable. At least that is my opinion, Albert Blankert has another idea about this.

If you were to imagine the music being preformed in Vermeer's paintings of musical themes, do any particular pieces or composers come to mind?

As I said, I would take the amateur harpsichord manuscripts, and make my own arrangements for the cittern of popular tunes of the time as there are no cittern prints or manuscripts from that period. I think a Vermeer cd would be a great thing to make: most music would be rather quiet, no virtuoso display, just playing for oneself, filling in the silence. Virginals, cittern, lute, guitar, all delicate instruments. This Vermeer cd would sound completely different from the Jan Steen CD I made with Camerata Trajectina, with all its funny songs, folk music and loud instruments.

In Vermeer's time, various debates ensued regarding painting and the arts among elite connoisseurs. Artist and art theorist Gérard de Lairesse affirmed the superiority of history painting (the "Antique" mode) over what is now called genre painting (the "Modern" mode as de Lairesse termed it) of which Vermeer was a proponent. The Renaissance debate as to which of the two visual arts, painting or sculpture, was more faithful to nature, was still alive. In musical circles, which discussion would we have most likely heard?

In Vermeer's time probably the preference for either the Italian or the French style, or perhaps still about the Italian-inspired baroque music (seconda prattica) versus the traditional Dutch style which was still based on the sixteenth century renaissance-tradition.