"The depiction of women and young girls employed in needlework such as lace-making was no rarity in Vermeer’s time. These activities stood for diligence, docility, and female domestic virtues in general. Lace-making was part of a young girl’s education, preparing her for her future role as housewife. In a painting from 1654, the Leiden artist Quiringh Gerritsz van Brekelenkam (1622/29–1669/79), depicted three girls making lace under the instruction of an older woman (fig. 1). It is evidently an educational establishment, as besides the four cushions in use there are another four stored on the shelf on the wall. A further related type of picture belongs to the next phase in the life of a young woman: while she is occupied with her needlework, a young man pays her court. However, most of the paintings feature older women busy with their needlework; Nicolaes Maes (1634–1693) in particular repeatedly places them in charming domestic scenes (fig. 2)."Gregor Weber, "Up Close," in VERMEER, ed. Pieter Roelofs & Gregor Weber, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2023, 198.

Quiringh Gerritsz van Brekelenkam

1654

Oil on panel, 62.5 × 86.5 cm.

Private collection

Nicolaes Maes

1655

Oil on panel, 38.8 x 35.9 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

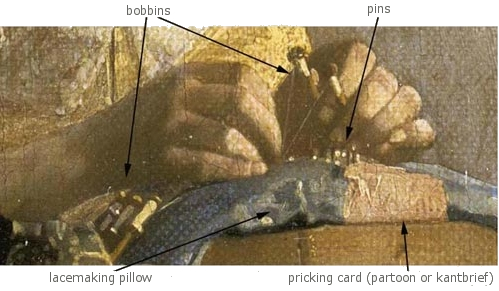

Although we cannot directly see the kind of lace the girl is making, we can draw some conclusions from her tools which Vermeer has rendered with sufficient precision (fig. 1). The girl rests her hands on a rather flat, light-blue lacemaking pillow, nowadays called a "cookie"-pillow,The "cookie"-pillow is typically round and relatively flat, resembling a large cookie, which is where its name likely comes from. This shape is quite distinct from the longer, cylindrical bolster pillow. This type of pillow is generally used for making shorter pieces or strips of lace, as opposed to the longer continuous strips that are created on a bolster pillow. It's well-suited for projects that require turning the work frequently, such as doilies or circular lace patterns. Like other lacemaking pillows, the "cookie"-pillow is filled with a material that is firm enough to hold pins securely yet soft enough to allow for easy pinning. The "cookie"-pillow can accommodate a variety of lace patterns and is especially useful for geometric designs that involve frequent direction changes. owing to its round form. This kind of pillow served to make shorter pieces or strips of lace. Another long, thick, tube-like "bolster"-pillowA "bolster" pillow, in the context of lacemaking, is a specific type of pillow used for creating bobbin lace. Its distinct cylindrical shape sets it apart from other types of lacemaking pillows, like the flatter "cookie" pillows. It is typically long and cylindrical, resembling a bolster cushion used for bedding. This tubular shape allows for the making of longer continuous strips of lace. The cylindrical shape is particularly suited for making yardage, which are longer strips of lace. The lace pattern develops along the length of the pillow, and the worked lace can be rolled around the pillow as the work progresses. Unlike some other lacemaking pillows, bolster pillows are generally less portable due to their size and shape. was frequently employed to produce yardage (long strips of lace) but does not seem to be the case in Vermeer's The Lacemaker (fig. 3).

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1669–1671

Oil on canvas on panel, 24.5 x 21 cm.

Musée du Louvre, Paris

The light brownish pricking card (patroonPatroons act as a blueprint for the lace-making process, outling the arrangement of stitches, knots, and other elements required to produce a particular lace pattern. Since onsistency is essential in lace making to ensure that the lace piece has a uniform and cohesive appearance, patroons help lace makers maintain consistent patterns and sizes throughout their work. Thus, they are also indespensible tools for both learning and teaching lace making. Beginners can follow patroons to practice and improve their skills, while experienced lace makers can design and share their own patterns. Many lace-making traditions have unique and intricate patterns that are passed down through generations. Patroons play a crucial role in preserving these traditional designs. or kantbrief) in Vermeer's painting, is partly visible, fixed on the blue pillow (fig. 2). In former times, the patroon was made of parchment.In the seventeenth century, patroons were often made of parchment due to several reasons. Parchment, made from animal skin, was more durable than paper. This durability was essential for lace patterns, as they needed to withstand frequent handling, pinning, and unpinning during the lace-making process. Its smooth and firm surface was ideal for preserving the fine details of lace patterns. This allowed for precise creation and replication of complex lace designs. Parchment could also endure the repeated insertion and removal of pins without tearing or deteriorating as quickly as paper would, and it tends to be more stable than paper in different environmental conditions. It's less prone to warping or reacting to humidity, which is crucial for maintaining the accuracy of the lace pattern throughout the intricate and detailed process of lace making. The strength and durability of parchment made it reusable. Patterns could be used multiple times, making them more cost-effective over time, especially important for popular designs that were in frequent demand. Although they are obviously not visible in Vermeer's painting, little holes were pricked onto this card to establish the desired pattern. Pins were inserted carefully into every hole. This preparatory phase was, and still is, very time consuming work requiring complete concentration in order to avoid any mistake that would afterwards destroy the whole work.

The little silvery pins with their globular reflections (they closely recall an optical phenomenon produced by the camera obscura called halations or disks of confusion) (fig. 4) from the incoming light are visible quite well in Vermeer's painting even though they have been somewhat abstracted. Around these pins the threads, furnished by the bobbins, are interwoven and crossed according to the pattern. The principal movements are the "twist" and the "cross," but there are numerous other techniques.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1669–1671

Oil on canvas on panel, 24.5 x 21 cm.

Musée du Louvre, Paris

The bobbins appear to be the common ones used during the sixteenth and seventeenth century. In the sixteenth century they may have been made of bone. Bobbin lace was commonly referred to as bone lace in that time but normally bobbins were made of wood, with the typical drop-like butt at the end for the weight to hold the threads in tension.

The bobbins are always used in pairs, which Vermeer rendered quite correctly. New pairs are added gradually as the work proceeds, so that at the end there are often hundreds of bobbins in use, which an experienced lacemaker is able to distinguish. Nowadays little colored balls help distinguish one from another. It would appear that Vermeer's young girl at the beginning of her work since she is working on the upper part of the card, with only a few visible bobbins.

The taut threads are miraculously rendered in Vermeer's painting with two hair-thin lines of light-colored paint. In order to appreciate the precision of such a passage it should be remembered that the whole painting is little more than eight inches wide (23.9 x 20.5 cm.).

Bobbin Lace

There are two principal groups of bobbin lace according to their working methods: the so-called non-continuous and the continuous lace. For the non-continuous lace each motif is made separately, later sewed together. In the non-continuous method both the ground (or "mesh") and the pattern are made all in one from the beginning to the end, using always the same number of bobbins resulting in a large number of bobbins from the start.

A very common kind of lace in Vermeer's day was (and still is) the stropkan, torchon-lace (from French for "towel" or "dishcloth"), sometimes also called "beggar's lace," probably due to the relative simplicity with which it is made together with its somewhat broader appearance caused by the coarser threads. It has a linear, geometrical design rather than with flowers or leaves. This makes it suitable for beginners since there are only a few curves to be done. It is based on a rectangular grid with angles of ninety and forty-five degrees. This makes it a strong fabric withstanding wear and washing better than other laces.

What Kind of Lace is Vermeer's Girl Making?

So what kind of lace may the girl in Vermeer's painting actually making? Of course, we must take to account that Vermeer most likely did not paint exactly what he saw with photographic precision. However, an educated guess would be that she is working on a rather short piece of lace, perhaps a geometric motif for non-continuous lace or a short stripe later to be attached to a piece of linen, for instance for a small tablecloth or runner or for a cushion. She is certainly not making a very complicated pattern or non-continuous lace, for which she would have far more bobbins at hand and would probably use a "bolster" pillow.