Of many Arts, one surpasses all. For the maiden seated at her work flashes the smooth balls and thousand threads into the circle, ... and from this, her amusement, makes as much profit as a man earns by the sweat of his brow, and no maiden ever complains, at even, of the length of the day. The issue is a fine web, which feeds the pride of the whole globe; which surrounds with its fine border cloaks and tuckers, and shows grandly round the throats and hands of Kings.

Jacob van Eyck, 1651.

Lace (French, dentelle; Spanish, encaje; German, Spitze; Italian, merletto). Lace is a transparent fabric worked with needles, with bobbins, or with crochet hooks, by sewing, knotting, or intertwining threads of various materials including gold, silver, silk, cotton, aloe fibers, and most commonly, linen.

Hans Memling

c. 1485–1490

– Oil on oak panel, 130.3 x 160 cm.

Louvre Museum, Paris

The origin of lace, as a separate craft, is disputed by historians. One Italian claim cites a will from 1493 by a member of the Milanese Sforza family. A Flemish claim points to lace on the alb of a worshiping priest in a painting from around 1485 by Hans Memling (fig. 1). But since lace evolved from other techniques, it is impossible to say that it originated in any one place. However, some authors speculate that lace manufacturing began in Ancient Rome, based on the discovery of small bone cylinders in the shape of bobbins. Firm evidence of true lace appears in the fifteenth century, when Charles V decreed that lacemaking should be taught in schools and convents in the Belgian provinces. During this period of enlightenment, the making of lace was firmly based within the domain of fashion. Specifically, lace was designed to replace embroidery, allowing dresses to be easily transformed to follow varying fashion styles. Lace developed from the embroidery technique of cutwork, whereby a design is cut out of a woven cloth. The edges of the cut sections are then secured with thread, both to stabilize the design and to add decorative texture. During the sixteenth century, the technique of lacemaking was freed from a woven foundation, thus evolving into a distinct fabric in its own right.Melinda Watt, "Textile Production in Europe: Lace, 1600–1800," Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed November 28, 2023.

Bobbin Lace

Essentially, there are two kinds of lace: needlepoint lace and bobbin lace. Both involve the manipulation of fine linen thread, each being named after the tools used in its creation.. Needlepoint lace is made with a single-thread technique using embroidery stitches, while bobbin lace, which developed after needlepoint lace, employs a variety of multiple-thread weaving techniques. Bobbin lace, also known as pillow lace because it is worked on a pillow, and bone lace, is so named for the early bobbins that were made of bone.. Bobbin lace is represented in Vermeer's Lacemaker. It was developed to provide tough yet decorative elements for the borders of garments, caps, pillows, tablecloths, and more. The production of the finest laces required many hours. The technique was perfected to such a high degree during the eighteenth century that the pictorial possibilities were virtually limitless. Even after techniques for "part lace" (made in pieces or motifs that are joined together on a ground, net, or mesh, or with plaits, bars, or legs) were perfected and lace could be made in pieces by several workers, each specializing in a specific type of stitch or pattern, lacemaking remained a tremendously slow process, and high-quality lace remained extremely expensive.Melinda Watt, "Textile Production in Europe: Lace, 1600–1800," Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed November 28, 2023,

Lacemaking techniques quickly spread to Spain and from there north to the Spanish Netherlands, France, Germany, and England. "During the Elizabethan era, quintessentially known for its fashion, lace ruffs were worn in various forms by almost all social classes. Yards of lace were required for a single modest ruff, making the more elaborate ones extremely costly. However, ruffs were not the only lace items in demand at this time. Lace was used to trim anything from altar cloths to ecclesiastical vestments to tooth cloths (small napkins) and pillow beres (pillowcases)."Lara Cathcart, "Bobbin Lace," no longer accessible. By the late seventeenth century, lacemaking centers in northern Europe had surpassed Italy in producing the most fashionable designs. Although France set the trends, Flemish lace consistently rivaled the French, largely due to the unsurpassed quality of its linen thread.

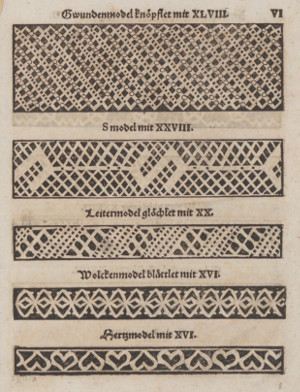

Given the scarcity of dated bobbin lace samples of the mid-sixteenth century, researchers rely heavily on early pattern books from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to chart the development of the art. The first known lacemaking pattern books originated in sixteenth-century Italy. The earliest documentation of bobbin lace—Vermeer's lacemaking girl clearly making bobbin lace—is the pattern book Nûw Modelbuch, Allerley Gattungen Däntelschn (fig. 2 & 3), by an author identified only as "R. M." The Nûw Modelbuch, a copy of which is preserved in the Zentralbibliothek Zürich, was printed in 1561 by Christopher Froschower in Zurich. "The title page of the Nüw Modelbuch is the earliest representation of a bobbin lacemaker known. The bobbins hang off the pillow (fig. 4), and the lacemakers appear to be working with an 'underhand' position, while securing the work with pins with the right hand. The bobbins themselves hang off the front of the pillow. This technique, surviving to this day and known as "working in the air," is especially useful for executing plaited laces. This contrasts with the Flemish technique where an overhand position is used, and the bobbins are laid flat on the pillow and manipulated with the fingers. This facilitates the turning of corners in the pattern."Laurie Waters, "A New Interpretation of Certain Bobbin Lace Patterns in Le Pompe, 1559," in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings (Paper 754), accessed November 27, 2023.

R. M.

Printed by Christoph Froschauer

Zûrich, 1561

R. M.

Printed by Christoph Froschauer

Zûrich, 1561

R. M.

Printed by Christoph Froschauer

Zûrich, 1561

Another early depiction of bobbin lace production is found in the work of Flemish painter, Maerten de Vos (c. 1534–1603), in a series of etchings called The Seven Ages of Man, which date from c. 1580–1585. The series is based on the planets and in the print called Venus, there is a young girl working on a lace pillow in the lower right hand side of the print (fig. 5).

Maerten de Vos

c. 1580–1585

Engraving on paper, 31.1 x 22.2 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In 1557, the Nûw Modelbuch was followed by Le Pompe, Opera Nova, nella qvale si ritrovano varie & dinerse sorti di mostre, per poter far Cordelle ouero Bindelle, d’oro, di Seta, di Filo, ouero di altra cosa … produced by the Sessa brothers in Venice. Following the aforementioned volumes, little was published until Isabetta Catanea Parasole's Speccio delle virtuose donne (The Mirror of Virtuous Women), published in Rome in 1595 (fig. 6). Unfortunately, the early pattern books contain no working instructions so interpretation of the patterns is left to the lacemaker. In any case, the pattern books bear evidence that bobbin lace did not start simple and become complex: rather they show from the beginning complexity and variety of working methods.

Isabetta Catanea Parasole

1595 (Rome)

Initially used by the clergy in the early Catholic Church as part of vestments in religious ceremonies but did not come into widespread use until the sixteenth century in the northwestern part of the European continent. The late sixteenth century marked the rapid development of lace, both needle lace and bobbin lace became dominant in both fashionas well as home décor. Lace was used for enhancing the beauty of collars and cuffs, needle. The popularity of lace increased rapidly and the cottage industry of lace making spread throughout Europe. But "lace was more than just a sumptuous and highly coveted luxury, affordable by only the privileged and well-born. It was also the product of an industry that provided a living to thousands of workers. It formed a considerable portion of the revenue of many nations, and played a role in history that goes largely unrecognized and unremarked today.""History of Lace," accessed November 27, 2023.

The Flanders, particularly Brussels, became one of the principal and renowned centers, became one of principal and renowned centers for lacemaking and its trade in Northern Europe. Lacemaking, together with linen weaving and whitework, was nevertheless practiced in the Northern Provinces as well, and the particularly fine woven linen from Holland had been already praised by Fynes Moryson after his journeys through the Low Countries in the 1590s.Patricia Wardle, "Needle and Bobbin in Seventeenth-century Holland," Bulletin of the Needle & Bobbin Club CXVI (1983): 3, accessed November 27, 202. The English diarist Samuel Pepys often wrote about the lace used for his, his wife's, and his acquaintances' clothing, and on May 10, 1669, noted that he intended to remove the gold lace from the sleeves of his coat "as it is fit [he] should," possibly in order to avoid charges of ostentatious living.

"For lower-class women, needlework and lacemaking could serve as vital sources of income. While upper- and middle-class ladies might have possessed the skill to make lace, the demand to supply a large household's needs could have exceeded their capabilities, unless they sought assistance, such as hiring a local woman to provide these services. Enlisting the help of another woman to create lace allowed the housewife to maintain appearances within her home, while providing a working-class woman with a source of income. Consequently, these skills could serve as a reliable means of support if a working-class family faced financial hardship. Commercializing a woman's lacemaking abilities also alleviated the strain on family resources, and it even enabled her to save for her own dowry. In this manner, lace and lacemaking became intertwined with domestic life, filling the physical home and exemplifying a woman's moral integrity and industrious nature." "Ideals of Femininity in the Dutch Republic: Analyzing Systems of Class, Gender, and Power in Caspar Netscher's 'Lacemaker' (1662)", "Lacemaking in the Dutch Republic," accessed November 29, 2023.

Demand for lace was so high and widespread that many women became lacemakers. Noblewomen founded lace schools for village girls, their patronage being paid for in lace, no doubt. Children of both genders were enrolled at about age five or so, with boys usually leaving as they grew strong enough for harder labor; in the seventtenth century the craft of lace making was a female domain. Girls as young as nine would be fully trained lace makers. Life for a lacemaking student was not easy. Even children worked from dawn till dusk, often in crowded, unventilated rooms without even the most primitive of sanitary facilities. Far worse were the conditions of the many Dutch women and children who made their livelihood with needlework, forced to spin the incredibly fine threadThese days, these strains of flax have been lost because the use of modern day fertilizers has meant that the plant fibers are no longer as fine as they once were. used to make the lace. These poor souls plied their trade in damp and darkness. The fiber would break if it dried out, so the spinners frequently worked in basements lit by a pinhole in a shutter that allowed only a single beam of light to fall upon their thread. It is not unheard of that these girls would be blind by the age of 30. Once trained, lacemakers were, however, no longer a burden on the family's resources. A girl could save towards her own dowry. She could continue to make lace after she married to contribute to her household's income and if she was widowed, she could support herself and her children. This newfound economic empowerment, coupled with the Queen as a role model, may have sown the seeds for social change, leading towards today's concept of female independence.

Dutch Lace

In the Netherlands, needlework was normally done by the women of the household whether rich or poor. It was a matter of course that young girls were taught sewing, embroidery and lacemaking, frequently in order to provide economic support for their parents. However, alongside these household women, there were also a considerable number of professional needleworkers, known as naaisters, who did sewing and needlework for a livelihood. A sharp distinction was made between those who worked with wool and those who worked with other materials. Those working with wool were organized into guilds, while the latter, perhaps because they were simply too many and would have been impossible to control, were not. The reason for naming it Dutch lace is simple: the lace was made in the Flanders province for export to Holland. Dutch lace is also called Cauliflower or Chrysanthemum lace because of the pattern. In the many portraits of that period, we can see that Dutch lace was a thick, closely worked, strong lace. It formed a nice effect and contrast on their costumes. Dutch laces became famous because of the quality of its flax thread. The Flemish thread was bleached in Harlem (Holland) and was considered the best flax thread in the world.

Stories written down by English travelers from the seventeenth century tell us that Dutch houses were full of lace. Dutch lace was used not only to decorate garments but also for adorning household objects. Even their brasses and warming pans were muffled in laces. The people of Holland had unusual customs with lace. For example, they tied lace around the door knocker of their home to announce a new born baby. This was intended not only as a decoration but it also had a practical purpose. The baby would not wake up from knocking because the lace deadened the sound of the door knocker. Dutch lace was exported to other parts of Europe and America through Holland.

Dutch cities maintained orphanages, like Amsterdam (the Maagdenhuis), Haarlem, or Dordrecht (the Holy Ghost orphanage) where the young girls, beside the regular school lessons received lessons in needlework by special sewing-mistresses. At the same time they worked long hours each day to earn some money.

Furthermore, there existed religious communities, like "De Hoek" in Haarlem, normally Catholic, which ran schools for children of needy parents in which the girls were contemporarily instructed in the Catholic religion and taught sewing and bobbin lacemaking as trades. Similar schools attached to communities were found in Gouda and Delft and it is likely that Vermeer would have been aware of their presence due to his tie to the Catholic faith. The women who taught needlework in these schools were called klopjes, Catholic women who were neither nuns nor laywomen, but lead a life dedicated to their religion. In the villages these schools, which were always private, were for the most part little more than child-minding establishments, where young children were taught to knit and sew along with the Alphabet as well. In the towns they provided a form of apprenticeship opportunity, whereby girls could learn a trade. The girls where placed at these schools at the age of around ten to twelve and later began to earn something.Patricia Wardle, "Needle and Bobbin in Seventeenth-century Holland," Bulletin of the Needle & Bobbin Club CXVI (1983): 6–7, accessed November 27, 2023.

The lacemaking industry in Holland had never reached the dimensions that it did in the Southern Netherlands, and the great part of the lace used there came from Flanders. Nevertheless, a considerable amount of bobbin lace, known in those times as speldewerk ("pin work"), was made in Holland even though it was of inferior quality. In some cases special bobbin lace workrooms (e.i., Groningen in 1674) were so profitable that the authorities decided to set up such workrooms in a house next to the orphanage, where the girls could be supervised by the mistresses.

The trade of the speldewerkster or bobbin lacemaker was normally a separate one from that from linen seamstress, although some of the seamstress were also able to make lace and teach lacemaking.

As fashion became more refined, lace patterns, particularly for collars and cuffs, evolved. from relatively simple ones to very fine, elaborately made pieces, whereby special patterns soon became closely related with a single town, where it had come from. For example, in portraits by Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck from Haarlem, we can identify certain types of lace (fig. 7) which may be a local fashion or have come from a local source, such as the Haarlem school "De Hoek."Patricia Wardle, "Needle and Bobbin in Seventeenth-century Holland," Bulletin of the Needle & Bobbin Club CXVI (1983): 10–11, accessed November 27, 2023.

Johannes Cornelisz. Verspronck

1640–1664

Oil on canvas, Oil on canvas, 81.3 x 66 cm.

Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede

The woman's collar displays borders of bobbin lace using additional colored threads.

The Technique of Bobbin Lacemaking

Bobbin laceUnfortunately, there were only two pattern books which where published in the 16th century that where devoted to bobbin lace. These two books where both published around 1560. The first, Le Pompe, was published in two volumes in 1557 in Venice. The second was published in 1560. Nüw Modelbuch was printed in Zurich (Switzerland) in 1561. can be conveniently divided into two groups based on the working methods involved: first, non-continuous laces (à pièce rapportées), and second, so-called "straight" or continuous laces (fig. 8 & 9). Bobbins serve several functions: they store the thread for the lace, act as handles to move the thread, and weight the threads to maintain tension against the pins.. "Bobbin lace is worked on a firm pillow over a pricked pattern. Thread is wound on bobbin pairs and twisted around pins set in the pattern or "pricking" until the tension of the work holds the design in place. Bobbin lace was sometimes called "pillow lace" for the pillow used to hold the pins, or "bone lace" because fish bones were used by lacemakers who couldn't afford pins (and/or because small bones were sometimes used as bobbins). Bobbins are wound and used in pairs. It is best to wind half of the thread onto one bobbin and then the other half onto the other. It is important to always wind the thread onto the bobbin in the same direction.

the pattern (kantbrief) and the bobbins (kantklosjes)

All bobbin lace is the result of two simple movements—the "cross" and the "twist" just as the most intricate knitted designs are formed of the basic "knit" and "purl" stitches. Regional differences in lace patterns and in shapes of lace bobbins arose but "Torchon" was a basic style of bobbin lace made through out Europe. Usually made from linen thread, it was a surprisingly sturdy lace (the name means "dishcloth," probably a comment on its washablity). (also called "ground") or woven to form solid shapes, depending on the type of lace to be made."Lara Cathcart, "Bobbin Lace," no longer accessible. An experienced lacemaker (speldewerker or kantkloster today) is able to work with one hundred or even more bobbins very quickly.

The patterns (patroons or kantbrieven) were originally made of parchment for increased stability. The threads were normally made of linen, cotton or silk although human hair was used exceptionally. For costly designs gold and silver threads are inserted, others employ additional colored threads or ornamental elements attached after the lace was completed.

In Vermeer's painting The Lacemaker, we can clearly distinguish the bobbins, the brownish kantbrieven, the light blue lacemaking cushion, and even a unique three-legged adjustable lacemaking table.

"The Flowers of Flanders: Seventeenth-Century Flemish Bobbin Tape Lace"

During the first half of the seventeenth century, bobbin-lace techniques multiplied and spread throughout Europe. The result, in the United Provinces of Flanders, was the production of fine tape laces known as Flemish bobbin tape laces. The dark, rich colors of fine wool and velvet clothing showed off the dense, wide textured white laces to perfection.

The prosperous burghers and members of the upper classes of society whose portraits were painted by Rembrandt and other artists of the period wore clothing heavily decorated with Flemish tape laces. Rembrandt's Portrait of a Woman (fig. 10) offers a fine example of the Flemish bobbin tape lace of the period. The subject is dressed in characteristically modest but fashionable attire. Her clothing includes three different Flemish tape laces. A wide, flat insertion forming the central portion of the broad collar is connected to a wide edging of deep symmetrical scallops. A third lace, comprising small rounded scallops of separate petals joined by tiny braids and sewings, edges her cap. In the collar, a relatively small plain linen section extends from the middle of the neck to the collarbone and acts as a base for both the square lace insertion and the scalloped lace edging. The shape and depth of the former copy the squared necklines of fashionable gowns of the period. In this lace, flowing, circular floral forms alternate with smaller, four-petaled flowers. At the inner corners of the insertion, a vase motif with a narrow base and broad top lets the lace change direction in a symmetrical and continuous line without having to be folded or overlapped. A more complex version of this simple vase shape recurs in the wide lace edging.Marini Harang, "The Flowers of Flanders: Seventeenth-Century Flemish Bobbin Tape Lace," PieceWork: All this by Hand, June 1994, accessed November 23, 2003.

Rembrandt van Rijn

1635

Oil on panel, 77.5 x 64.8 cm.

Cleveland Museum of Art

The entire insertion band has been worked in a continuous line of dense bobbin-lace cloth-stitch tape that has been curled back upon itself and joined with simple sewings. The spaces between the large, circular flowers and the smaller, four-petaled flowers, as well those between the floral motifs and the vase motif, have been filled with small two- or four-strand braids and narrow lace tapes.

Two layers of deeply scalloped tape lace in a vase and floral design extend the collar to form a small cape over the woman's torso and shoulders. The upper layer rests upon the lower one in soft folds: the lower layer is made in the same overall design as the upper, but its motifs are larger. The entire collar is full enough to meet and slightly overlap in the front without a closure.

The delicate Flemish bobbin-tape laces shown in the Rembrandt portrait represent a step in the development of bobbin lace techniques in Europe. They reflect a prosperous time, and the people, especially the members of a well-to-do merchant class, who helped create the prosperity, benefited from it, and were pleased to wear its finely made products.

Resources

- Blankert, Albert, and Louis P. Grijp. "An Adjustable Leg and Book: Lacemakers by Vermeer and Others, and Bredero’s Groot Lied-boeck in One by Dou." In Shop Talk: Studies in Honor of Seymour Slive Presented on his Seventy-Fifth Birthday, edited by Cynthia P. Schneider, William W. Robinson, and Alice I. Davies. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1995.

- Burkhard, Claire. Nüw Modelbuch facsimile published as part of Fascinating Bobbin Lace. Haupt, 1986.

- Dye, Gilian. Silver Threads & Going for Gold. The Lace Guild, 2001.

- Earnshaw, Pat. Identification of Lace. Shire Publications, 1989.

- Hopkin, David. "Legends of Lace: Commerce and Ideology in Narratives of Women’s Domestic Craft Production." Journal Fabula, accessed November 28, 2023. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/fabula-2021-0013/html?lang=en.

- Levey, Santina. Lace, a history. Maney, 1990.

- Nottingham, Pamela. The Technique of Bobbin Lace. Batsford, 1976. ISBN 0-7134-3230-6.

- Ploeg, Sophie. The Lace Trail - Fabric and Lace in Early 17th Century Portraiture. An Interpretation in Paint. Blurb Bookstore, 2014. https://www.blurb.co.uk/bookstore/detail/5410344-the-lace-trail.

- Shepherd, Rosemary. An Early Lace Workbook. Lace Daisy Press, 2009.

- Toomer, Heather. Antique Lace: Identifying Types & Techniques. Schiffer Publishing Ltd (US), 2001.

- Wardle, Patricia. "Needle and Bobbin in Seventeenth-century Holland." Bulletin of the Needle & Bobbin Club CXVI (1983): 6–7, accessed November 27, 2023. http://www2.cs.arizona.edu/patterns/weaving/periodicals/nb_83.pdf.

- Watt, Melinda. "Textile Production in Europe: Lace, 1600–1800." Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed November 28, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/txt_l/hd_txt_l.htm.

Websites

- Cathcart, Lara. "Bobbin Lace." No longer accessible.

- Brassac, Esther. "Short History of Bobbin Lace"

- The History of Lace, Lacemlkaers's Lace. Accessed November 29, 2023.

- Marla Mallett, "The Structures of Antique Lace." No longer accessible.