Click here to view the list of Vermeer paintings classified according to popularity.

Click here to see the a bar graph of Vermeer paintings classified according to popularity.

Perhaps no other artist except Vermeer can boast such an outstanding ratio of masterworks to total artistic output. At least eight, almost a quarter of the artist's known production, can be considered masterworks of universal import. And as never before art historians, art critics, novelists, poets, film directors and ordinary lay people are inebriated by his canvases. In a recent public poll in the Netherlands, Vermeer advanced for the first time past the great Rembrandt van Rijn as the nation's most cherished painter. One critic (Peter Schjeldahl in the New Yorker) wrote that admiration has grown such that Vermeer is now "displacing Raphael as Europe's cynosure of artistic perfection."

occasion of the Vermeer's Women exhibition (2011).

However, Vermeer did not enjoy such unbridled esteem in his own time or in the years following his premature death. His resurrection and subsequent apotheosis began much later in the 1860s when French art critic and left-wing politician Théophile Thoré-Bürger published a series of articles eulogizing the painter's forgotten works. From then on Vermeer's star has steadily risen.

During the 1920s, Vermeer's canvases came into the sights of moneyed American art collectors who scoured the European continent in search of any painting that resembled a Vermeer and could be dislodged from its owner. This explains why almost half of Vermeer's oeuvre, and a number of forgeries, are in American collections. The post-WWII discovery of a failed Dutch artist who had forged various Vermeer paintings which had been enthusiastically accepted by leading Dutch scholars sobered the global art market overnight. The scandal and international trial that ensued had two beneficial consequences: Vermeer's fame was boosted to new heights and his oeuvre pared down more or less to its present-day dimension of 35 (36?) paintings.

By the 1950s, Vermeer's name had been consolidated among the art-going public but following the legendary Washington/The Hague Vermeer exhibitThe Washington venue of the exhibition tallied more than 330,000 visitors notwithstanding a government shutdown and gelid winter. of 21 authentic paintings in 1994–1995—considered one of the most important art exhibitions of all time—the artist's fame breached the periphery of the art world and became a familiar household name.

And yet, the Washington exhibition was topped only twenty years later. In February 2022, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam hosted its most successful exhibition ever, showcasing 28 of the 36 works—two of which had been restored since the Washington exhibition—generally attributed to Vermeer. These masterpieces were sourced from collections around the globe. The exhibition, which concluded after a 16-week run, was lauded by the national art and history museum of the Netherlands as an unparalleled success. It drew an impressive 650,000 visitors from 113 countries. Due to high demand, tickets had to be reissued and exhibition hours extended, even though the interest in attending this extraordinary event greatly exceeded availability. In addition to the exquisite paintings, the exhibition was commended for its meticulous organization and decor, designed by the French architect, Jean-Michel. Each artwork was surrounded by a simple semicircular balustrade, facilitating close examination while also managing the flow of the crowd. Thick velvet curtains separated the paintings, muffling sound and providing an intimate viewing experience. Minimal texts and the absence of comparative works or distracting videos further enhanced the ambiance. This minimalist approach allowed Vermeer's intricate details to captivate visitors, turning the minute into the magnificent. The exhibition received overwhelming praise from the media, earning standing ovations and numerous five-star reviews. Some critics even hailed it as "the exhibition of the century," despite there being seventy-five years left in the century.

Vermeer's mystique: is it overrated?

While Vermeer's appeal is universal, it should be noted that the taste of the general public does not always align itself with that of art specialists, who, in any case, are wont to avoid making personal value judgments, especially negative ones regarding the master's works. In public scholars prefer to discuss each work in terms of "meaning" or the relation that one painting may bear to others by the same artist or to comparable Dutch paintings. An example of the disparity between popular sentiment and scholarly interest can be easily understood by comparing the amount of literature dedicated to deciphering the presumed symbolic meaning hidden behind the icy façade of the London A Lady Standing at a Virginal against the handful of visitors who delay their gallery stroll no more than a few seconds to view the painting and quickly walk away to view more amenable images.

Ivan Gaskell, one of the few scholars who has addressed the matter of Vermeer's fame at any length, utilized a comparison between Rembrandt and Vermeer to explain the latter's mystique and unstoppable rise to the upper echelons of world culture.

But not all art historians, or even painters, view Vermeer's overwhelming popularity in the same manner. In an interview, the famous English painter Francis Bacon stated, "Everybody likes Vermeer, except me. He doesn't mean anything, he has no significance." Princeton specialist in Early Modern European History Theodore K. Rabb compares Vermeer to Rubens in an informative article that directly challenges Vermeer's claim to fame. Rabb questions why we prefer to quietly "ponder, explore and relish the limited but subtle beauties of Vermeer" in respect compared to the universal values of Peter Paul Rubens, the grandiose Baroque painter who defined his own age and left a lasting impact on the course of art history. Vermeer's painting had a negligent impact on the artists of his own time and none on those who followed.

Here are some attentive reflections from Rabb:Theodore K. Raab, "Why is Vermeer so revered?" The Art Newspaper 208 (December 2009): 39–40.

That such deification [of Vermeer] has taken place prompts an obvious speculation: why should this be? Taste is, of course, ineffable, but two considerations may be worth pondering. The first is the steady devaluation of history in both British and USA culture. As a serious pursuit, it is in steady decline, shrinking as a classroom subject and as a basis for public discourse. In that context, an artist's historical importance is easily devalued. That Raphael, like Rubens, owed huge debts to his forerunners, and in turn shaped the future, gives him little credit when aesthetic judgment comes to the fore. A second consideration is that recent generations have lost the capacity to appreciate the Biblical, classical and historical references that infuse Rubens's paintings. As cultural horizons contract, the private and domestic supplant the public and the grand. It may not be irrelevant that a Vermeer is likely to be visible only to a few people at one time, whereas a Rubens can tower over a crowd. We may be living, in other words, in an age that prefers small pleasures to large. We cannot settle into dreamy contemplation of Rubens. He overwhelms. He demands soaring, energetic attention.

Why are Vermeer's paintings so popular but so different from contemporary art?

If we are to trust the iconographers who have unearthed the messages that Vermeer's paintings were presumably intended for his contemporaries, such messages have not aged particularly well over the distance of 350 years. Moderation, temperance, and balance are no longer prime social values in a century which, instead, openly cultivates transgression, disinhibition, and an individualist search for freedom and pleasure, alongside traditional values. And no one needs to be reminded that 20th-century artists, often willfully abstruse, have made every effort to dismantle foundational artistic values of the past.

Obviously, the busy half-century of iconographic research loses none of its value for the scholarly world, and by now even most laymen would agree that it is important to know what were the artist's intentions were and how his contemporaries viewed his paintings even if such values no longer match our own. "The more we know, the better," is the cultural anthem that few are willing to debate.

Even though the didactic contents of Vermeer's paintings appear largely unusable for the great majority of those who profess love of his paintings, his tiny works command undiminishing respect on the part of both laymen and specialists. It may be that the artist's popularity relies substantially not so much on non-pictorial meanings or the moral messages but on the subjects themselves as they immediately appear to the eye and by the exquisite manner in which these subjects are depicted. Curiously, many of the artistic values of Vermeer's painting—in effect, the manner in which they are composed and depicted—seem to be at complete odds with those of the most successful art of our own age.

Could the global increase in the popularity of Vermeer's work indicate a spontaneous trend towards unmediated visual experience and artist/viewer communication? Is the concept of art as an educational instrument losing traction? Here is how Vermeer's work stacks up against the works of today's competitors.

Vermeer's art vs. contemporary forms of art

- Vermeer's works are small, even by seventeenth-century Dutch standards. Today's cutting-edge artists are inclined to work on a large, if not monumental, scale. Vermeer's hand-painted representations are "scaled down" versions of reality, such as the minuscule Lacemaker, while today's artist tends to "scale up"—see Jeff Koons's £12.9 m. Hanging Hearts.

- Vermeer produced a paltry number of paintings (35, perhaps 36 have survived but he probably made no more than 60) and very likely did not employ techniques to produce multiples. Today's artists seek out prominent platforms, both public and private, to exhibit their work, such as art fairs and public museums that attract thousands of viewers. The most famous and avidly collected painter of the twentieth century, Andy Warhol, left a countless number of works in an endless variety of techniques.

- Vermeer's paintings were created for private viewing. They were destined to be hung in discreet bourgeois family dwellings where only a select few could see them (public collections and commercial art galleries did not exist in the seventeenth century). Today's artists demand prominent, public or private platforms to exhibit their work including art fairs and public museums frequented by thousands of viewers.

- Vermeer's art is undemonstrative and evasive. Cutting-edge art tends to be invasive, brash, and deliberately disturbing.

- As far as we can understand, Vermeer proffered no substantial critique of any known artistic or social norm. Today's artist is almost universally critical of one or more aspects of his society, and his work is frequently conceived as a vehicle to direct social change.

- Vermeer's art represents daily life, or at least, a very close approximation of it.

- There is nothing overtly provocative, spectacular, miraculous, shocking, humorous, supernatural or extraordinary in Vermeer's subject matter. While he carefully staged his mise-en-scène interiors and contrived his compositions with painstaking attention, he never painted anything that could not have existed. His works evoke states of meditative calm. Frequently, the value of a contemporary work of art is judged by its novelty and its capacity to shock and provoke public debate.

- Vermeer accepted, and in one case rhetorically glorified, the canons of art of his age (see The Art of Painting). Today's cutting-edge artist challenges prevailing concepts of the art.

- Vermeer's art does not lend itself to the spoken word; it is essentially silent. The artist left no written documents regarding his art. Any of today's artists emphasize their point by adding explanatory documents, like exhibition catalogues, to their works or by giving widely publicized interviews

- Vermeer was deeply committed to his craft. An ever-increasing number of contemporary cutting-edge art is not physically created by the artist themselves. Moreover, classical easel painting is generally perceived as inferior to conceptual art forms.

- The appeal of Vermeer's art is simultaneously populist and lofty while today's art favors low-brow dialect (kitsch and vernacular) but comes across as elitist. Vermeer's art is inclusive where much of today's art is exclusive.

Below are listed 35 (36?) extant Vermeer paintings according to their popularity. This list is based on the number of unique page views that each painting receives on a yearly basis at the Essential Vermeer website. The almost totality of these visits originate from the index of the catalogue where at a glance the navigator may survey the titles and thumbnail images of Vermeer's complete oeuvre displayed in chronological order. There are some surprises. For example, the once iconic Lacemaker, reproduced on countless twentieth-century periodicals and advertisements, currently occupies only the twenty-second place with less than one-third of the visits received by the Girl with a Pearl Earring or The Milkmaid.

Vermeer's paintings listed according to popularity

This list was compiled utilizing the number of visits to Vermeer's paintings over a period of one full year on this Essential Vermeer website. Click on the thumbnail to access a high-resolution image of the painting. Click on the painting's title to access the interactive study of that painting.

Girl with a Pearl Earring

c. 1665 –1667Oil on canvas

46.5 x 40 cm. (18 1/4 x 15 1/4 in.)

Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, The Hague

museum contact

61,587 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

The popularity of the iconic Girl with a Pearl Earring necessitates no comment. An endless stream of posters, postcards, homemade photographic look-alikes, copies, slick advertisements, book covers, novels, and films that refer to the picture attest to its ever-widening fame. On the other hand, at the 1696 auction of 21 Vermeer paintings, this simple tronie (characteristic head study) fetched only 36 guilders (a bit above the average price for work of a good painting by a Dutch painter) while his own Milkmaid of comparable dimensions reached the considerable sum of 175 guilders, or almost 5 times the price of the former.

Incredibly, the painting was purchased in 1881 for next to nothing. In that year it was offered at a sale at an auction house in The Hague as a part of an art collection of a certain Mr. Braams. Victor de Stuers, an important art historian, recognized the exceptional quality of the painting and urged his friend Arnold des Tombe to buy it. In order not to arouse suspicion, De Steurs and De Tombe agreed not to bid against each other. Des Tombe acquired the painting for a mere two guilders, plus the buyer's premium of thirty cents.

The painting was not intended as a portrait but a so-called tronie, and there is no evidence regarding who might have posed for the picture.

The Milkmaid

c. 1657 –1661Oil on canvas

45.5 x 41 cm. (17 7/8 x 16 1/8 in.)

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

museum contact

34,583 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

This simple, dignified image of a kitchen maid pouring milk has come to represent both Dutch culture at large as a symbol of domestic virtue. It remains one of the few works by Vermeer that held its own after the artist died (subsequently, his oeuvre was dispersed throughout Europe and his name largely forgotten). The painting, like the Girl with a Pearl Earring, has been the subject of countless "elaborations" in the twentieth century, some tasteful, many not.

Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window

c. 1657 –1659Oil on canvas

83 x 64.5 cm. (32 3/4 x 25 3/8 in.)

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

(Old Masters Picture Gallery), Dresden

museum contact

25,192 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

This rather large canvas is one of Vermeer's most beloved works. The atmosphere of suspended time it emanates is so intense that it is impossible for the viewer to withdraw from the picture's simple story and cavernous space. It is also of great interest to the scholarly community because it is the first example of Vermeer's left-hand-corner-of-the-room motif and because the final layers of paint hide the many drastic revisions that the budding young artist made during the working process. These changes are of tantamount importance to understand the iconographic agenda of the painting and the artist's technical evolution. Its compositional failings are rarely noticed. Walter Liedtke wrote that no other work by the artist is so "beautifully imperfect."

The Art of Painting

c. 1662–1668Oil on canvas

120 x 100 cm. (47 1/4 x 39 3/8 in.)

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

museum contact

20,187 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

This large-scale canvas entrances laymen and savvy art scholars alike. Few painters could have pulled off such an unlikely studio setup (the picture hardly represents real working conditions of a seventeenth-century Dutch painter) or tamed such an accumulation of objects. The perfect perspectival construction draws one into the space in which light seems to fall as in a most natural manner. One may easily understand the impression that an art lover of the seventeenth century would have had when entering into the artist's studio.

The Girl with a Wine Glass

c. 1659–1662Oil on canvas

78 x 67 cm. (30 3/4 x 26 3/8 in.)

Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Braunschweig (Brunswick)

museum contact

18,142 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

The Girl with a Glass of Wine is a popular favorite even though it reproduces poorly and is housed in a small museum far from the international tourist trail. Many are puzzled by the girl's awkward grin although, it has been speculated that it may have been retouched. However, the exquisite treatment of rich-red satin dress, the pure, natural light that filters through the stained glass window and the almost physical sense of spatial depth of the painting were far beyond the reach of any other Dutch painter of the time.

Young Woman with a Water Pitcher

c. 1662–1665Oil on canvas

45.7 x 40.6 cm. (18 x 16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

museum contact

18,114 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

The Young Woman with a Water Pitcher is perhaps one of the very few paintings by Vermeer of which the composition finds no direct precedent. The figure's statuary pose, bird-like lightness and the room flooded with immaculate morning sunlight make this one of the most mesmerizing works of the artist's oeuvre. The knowledge of iconographic references seems superfluous to appreciate this work, perhaps one of the artist's most spiritually enlightening images. Its only shortcoming is that the museum-goer is not allowed take it home.

Woman with a Pearl Necklace

c. 1662–1665Oil on canvas

55 x 45 cm. (21 5/8 x 17 3/4 in.)

Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

museum contact

15,796 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

Similar to the Young Woman with a Water Pitcher, this work requires neither book learning nor familiarity with European painting traditions to appreciate in full. The blank wall, unique in European painting, creates a luminous frame of light for the young girl who sports a fancy fur-trimmed satin morning jacket and the latest hairdo. She is momentarily absorbed in her own image reflected across the room by a mirror hung on the shadowed wall on the opposite side of the picture. No reproduction, however faithful, can convey the impact of this simplest of Vermeer's interior scenes.

Woman in Blue Reading a Letter

c. 1662–1665Oil on canvas

46.5 x 39 cm. (18 1/4 x 15 3/8 in.)

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

museum contact

15,796 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

The Woman in Blue Reading a Letter is closely related to the two pictures above in composition and technique. The incredibly refined paint handling, that can only be truly appreciated by those who have had the fortune to see the real painting, makes it one of Vermeer's most delicate and profound testimonies of feminine nature, or at least that part of feminine nature that can be comprehended by a man. The woman appears to be enveloped in an invisible envelope of space that tenderly embraces her in cool morning light.

The Love Letter

c. 1667–1670Oil on canvas

44 x 38.5.cm. (17 3/8 x 15 1/8 in.)

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

museum contact

15,626 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

Strangely,this small but complex painting—the figures almost resembling miniatures—exerts a direct appeal that is at odds with the elaborate scene which attempts to keep the viewer at bay. In recent years, the painting's popularity may have been reinforced by its frequent travels as the star of temporary exhibitions all over the globe.

View of Delft

c. 1660–1663Oil on canvas

98.5 x 117.5 cm. (38 3/4 x 46 1/4 in.)

Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, The Hague

museum contact

15,521 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

View of Delft is one of the few works by Vermeer that had held its own after the death of the painter. In À la recherche du temps perdu, Marcel Proust dedicated a long passage to its "petit pan de mur jaune" (a little patch of yellow wall) that appears on the left-hand side of the painting. Near death, Proust's fictional writer Bergotte, weighs his own art against Vermeer's precious passage. "His dizziness increased; he fixed his gaze, like a child upon a yellow butterfly that it wants to catch, on the precious patch of wall. 'That's how I ought to have written,'s he said. 'My last books are too dry, I ought to have gone over them with a few layers of colour, made my language precious in itself, like this little patch of yellow wall.'s Meanwhile he was not unconscious of the gravity of his condition. In a celestial pair of scales there appeared to him, weighing down one of the pans, his own life, while the other contained the little patch of wall so beautifully painted in yellow. He felt that he had rashly sacrificed the former for the latter."

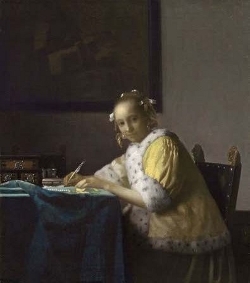

A Lady Writing

c. 1662–1667Oil on canvas

45 x 39.9 cm. (17 3/4 x 15 3/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

museum contact

15,490 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

A Lady Writing is one of Vermeer's simplest interiors. Although it does not reproduce well, this small canvas never fails to arrest the museum-goer even if the coloring appears a bit sour. The chiaroscural scheme is so effective that the viewer hardly questions just how the strong light that strikes the figures does not illuminate the background wall. This is one of the few pictures by Vermeer which calls directly on Rembrandt, in both the compositional scheme and the dramatic use of light.

The Music Lesson

c. 1662–1665Oil on canvas

73.3 x 64.5 cm. (28 7/8 x 25 3/8 in.)

The Royal Collection, The Windsor Castle

museum contact

14,757 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

The Music Lesson is one of Vermeer's most complex and accomplished works, a masterpiece of composition, perspective, light, and story-telling. The picture must be seen to appreciate its almost supernatural stillness. Unfortunately, it is infrequently on public display, but for any Vermeer devotee, it is alone worth a trip when it is accessible.

Officer and Laughing Girl

c. 1657–1660Oil on canvas

50.5 x 46 cm. (19 7/8 x 18 1/8 in.)

Frick Collection, New York

museum contact

14,439 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

It is impossible to anticipate the effect of this small picture through reproductions, even though the lighting at the Frick Collection is sorely insufficient.. The combination of the crisp morning light which plays upon the figures and furnishings, as well as the cheerfulness of the smartly dressed girl is so utterly convincing that few pass by this small picture without smiling.

The Procuress

1656Oil on canvas

143 x 130 cm. (56 1/8 x 51 1/8 in.)

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Old Masters Picture Gallery), Dresden

museum contact

14,221 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

Although the big, boisterous Procuress seems to share very little with the Vermeer most are familiar with, we should always remember he grew up in his father's inn which was no convent. And even if sex peddling, commonly practiced in inns, wasn't among his father's trades, the young boy couldn't have very well avoided scenes of prostitution elsewhere in Delft. Pictures of brothels had been immensely popular before Vermeer painted The Procuress, even though the motif was a bit dated.

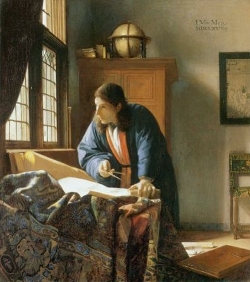

The Geographer

c. 1668–1669Oil on canvas

53 x 46.6 cm. (20 7/8 x 18 1/4 in.)

Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

museum contact

14,118 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

Girl with a Red Hat

c. 1665–1667Oil on panel

23.2 x 18.1 cm. (9 1/8 x 7 1/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

museum contact

13,743 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

Woman Holding a Balance

c. 1662–1665Oil on canvas

42.5 x 38 cm. (16 3/4 x 15 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

museum contact

13,729 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

This work was highly appreciated in its own time. In 1696, it was sold for 155 guilders at a posthumous auction of 21 Vermeer's paintings. With respect to its dimensions, the Woman Holding a Balance reached the second-highest price after The Milkmaid (175 guilders). Moreover, the painting was described in the sales catalogue as being "in a box," presumably a protective device reserved for the most precious works of art.

The Concert

c. 1663–1666Oil on canvas

72.5 x 64.7 cm. (28 1/2 x 25 1/2 in.)

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

museum contact

13,530 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

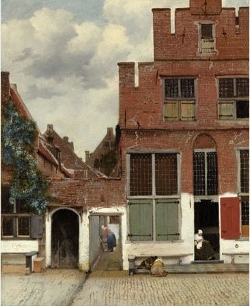

The Little Street

c. 1657–1661Oil on canvas

54.3 x 44 cm. (21 3/8 x 17 3/8 in.)

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

museum contact

13,305 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

The Little Street is one of Vermeer's most touching canvases, greeted with enthusiasm by all those who have the opportunity to see it. The sense of tranquility and intimacy can be appreciated only in front of the real picture.

A Maid Asleep

c. 1656–1657Oil on canvas

87.6 x 76.5 cm. (34 1/2 x 30 1/8 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

museum contact

13,296 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

Few museum visitors cast more than a sidelong glance at this somber canvas. It is far more popular among art historians who find the iconographical interpretation of this apparently straightforward interior, the first in the artist's career, particularly challenging. Although technically imperfect, it nonetheless signals a definitive break from the mode of history painting.

Christ in the House of Martha and Mary

c. 1654–1656Oil on canvas

160 x 142 cm. (63 x 55 7/8 in.)

National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

museum contact

12,364 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

The Lacemaker

c. 1669–1671Oil on canvas (attached to panel)

24.5 x 21 cm. (9 5/8 x 8 1/4 in.)

Musée du Louvre, Paris

museum contact

12,191 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

Towards the middle of the twentieth century, The Lacemaker was one of the most popular and most reproduced paintings by Vermeer (also a favorite of the Spanish surrealist painter Salvador Dalí). It is hard to imagine how such a subtle yet powerful image does not make it a favorite alongside the Girl with a Pearl Earring and The Milkmaid. The painting is nothing else if not a perfect exemplar of technique and composition.

12,151 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

Saint Praxedis

1655Oil on canvas

101.6 x 82.6 cm. (40 x 32 1/2 in.)

Kufu Company Inc., on long-term loan to the National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo

12,068 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

The authenticity of this painting is currently upheld by only one Vermeer authority, Arthur L. Wheelock Jr. Most laymen are puzzled by its subject matter, dimensions, and its broad execution so unlike anything Vermeer ever painted.

A Young Woman Seated at the Virginals

(attributed to Vermeer)Oil on canvas

c. 1670

25.2 x 20 cm. (9 7/8 x 7 7/8 in.)

The Leiden Collection, New York

11,984 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

After years of languishing in critical limbo, this painting was recently accepted as an authentic Vermeer by two foremost Vermeer experts, Walter Liedtke and Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. Although it is not always on public display (along with The Music Lesson in the Royal Collection, it is the only Vermeer in private hands) laymen generally find it more agreeable than art specialists who tend to believe it was painted in order to alleviate the artist's disastrous economic condition brought on by the war with France and the weight of his exceptionally large family.

Diana and her Companions

c. 1653–1656Oil on canvas

98.5 x 105 cm. (38 3/4 x 41 3/8 in.)

Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, The Hague

museum contact

11,822 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

The mythological subject, the somber mood and the rather sketchy quality of this early work do not attract many lookers in the Mauritshuis where it displayed only a few meters from the iconic Girl with a Pearl Earring.

Girl Interrupted in her Music

c. 1658–1661Oil on canvas

39.3 x 44.4 cm. (15 1/2 x 17 1/2 in.)

Frick Collection, New York

museum contact

11,205 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

This small work is one of the least popular interiors by Vermeer and one of the most neglected by art historians as well, owing, very probably, to its poor state of conservation. Nonetheless, a few exquisite passages (the windows, the still life and the lion-head finial chairs) have resisted the ravages of time and tell us something about the work's original air of hushed silence and delicacy of paint handling.

Mistress and Maid

c. 1666–1668Oil on canvas

90.2 x 78.7 cm. (35 1/2 x 31 in.)

Frick Collection, New York

museum contact

10,844 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

It is not entirely clear why such an opulent, delicately painted work has not become not a public favorite. The figure of the mistress, calm yet perplexed by the letter her maid is handing to her, is one of the artist's great interpretations of the female psyche, perhaps the finest.

Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid

c. 1670–1671Oil on canvas

71.1 x 58.4 cm. (28 x 23 in.)

National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

museum contact

10,463 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

For some reason, the hushed atmosphere and the fine accouterments of the writing mistress do not endear this work to the general public even though it was voted by the Irish the most beloved painting in their country. On the other hand, it is one of the most discussed by art historians who find its iconographic ramifications as subtle as the work's painting technique and compositional layout.

The Guitar Player

c. 1670–1673Oil on canvas

53 x 46.3 cm. (20 7/8 x 18 1/4 in.)

Kenwood House English Heritage as Trustees of the Iveagh Bequest, London

9,877 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

Some modern viewers are disturbed by the curious, generalized treatment of the girl's face (who is no conventional beauty). However, the canvas is preserved particularly well and is one of the few paintings of the seventeenth century that remains tacked on its original stretcher and has never been relined (even the wooden tacks are original). Unfortunately, the viewing conditions at the Kenwood House where this work hangs are almost prohibitive.

Allegory of Faith

c. 1670–1674Oil on canvas

114.3 x 88.9 cm. (45 x 35 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

museum contact

9,539 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

The religious subject, the rhetorical pose an accumulation of seemingly dsiparate objects in a bourgeois room make this work one of Vermeer's most neglected compositions. However, a few years after the artist's death it was sold at a considerable price compared to those reached by Vermeer's paintings a few years before, demonstrating that the perception of a work of art is deeply influenced by prevailing cultural bias.

Woman with a Lute

c. 1662–1665Oil on canvas

51.4 x 45.7 cm. (20 1/4 x 18 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

museum contact

8,848 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

Tthe Woman with a Lute is in a poor state of preservation, enough of the paint surface has survived to show that it is an authentic work by Vermeer. The foreground colors have darkened and the carpet which hangs on the table and the bass viol that lies on the floor are almost entirely illegible. Nonetheless, the intricately balanced composition and yearning attitude of the young lutenist lend the work a particular pathos, unique in the artist's oeuvre.

Study of a Young Woman

c. 1665–1674Oil on canvas

44.5 x 40 cm. (17 1/2 x 15 3/4 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

museum contact

8,418 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

This work has had the double misfortune of representing a rather homely young girl and being immediately comparable to the iconic Girl with a Pearl Earring. Otherwise, the painting is in an acceptable state of conservation and is full of its own moon-like mystery.

A Lady Seated at a Virginal

c. 1670–1675Oil on canvas

51.5 x 45.5 cm. (20 1/4 x 17 7/8 in.)

National Gallery, London

email contact

8,188 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

That art specialists do not respond to pictures in the same way as the museum-going public is clarified by comparing the lack of public enthusiasm for this work and the amount of art historical literature that has been dedicated to this London canvas. It is easy to have the picture all to one selfeven when the National Gallery is crowded.

Girl with a Flute

c. 1665–1670Oil on panel

20 x 17.8 cm. (7 7/8 x 7 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

museum contact

7,864 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

The Girl with a Flute has nt been well-preserved, which may be one of the reasons why laymen do not warm up to this little panel. The face of the young girl is only summarily rendered and may have never been brought to completion. The lack of finesse and the highlights make the eyes and skin seem particularly opaque. The psychological nuance that belongs to its companion work, the Girl with a Red Hat, was long stripped away by poor restoration. Nonetheless, viewers can console themselves with the brilliant passage of the fur trim (the left-hand sleeve has been clumsily overpainted) and the bizarre, oriental-looking hat, headgear that is rarely seen in Dutch painting.

The Glass of Wine

c. 1658–1661Oil on canvas

65 x 77 cm. (25 5/8 x 30 1/4 in.)

Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

museum contact

7,763 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

It is truly odd that this work is not among Vermeer's most popular paintings. It displays many of the artist's most characteristic motifs and details that would be envied by almost any Dutch interior painter of the time. Moreover, the brilliant original color scheme has been uncovered by recent restoration.

A Lady Standing at a Virginal

c. 1670–1674Oil on canvas

51.7 x 45.2 cm. (20 3/8 x 17 3/4 in.)

National Gallery, London

email contact

7,731 page views per year

(click here to see bar graph below)

Bar graph of the relative popularity of Vermeer's paintings

The bar graph below displays the total number of yearly website visits to each of Vermeer's paintings listed in the Complete Vermeer Catalogue. The vertical bar represents the number of visits each painting received. For example, the first bar to the extreme left shows that painting no. 1 received about 62,000 unique visits. The progressive numbers on the graph's horizontal axis refer to the order of the paintings by popularity. Thus, painting no. 1, which received 62,000 visits, refers to the Girl with a Pearl Earring.

Most visits to the individual paintings come from Complete Vermeer Catalogue index page where each painting is represented by a small thumbnail image, title, and other basic information arranged in chronological order. By clicking on the index titles, the visitor can access a page that provides in-depth information about the work.

It is evident from this graph that the greater part of Vermeer's paintings are grouped within a relatively limited range of approximately 15,000 to 11,000 visits per year. Occasionally, the difference between contiguous paintings is one hundred visits or less which may not express a meaningful preference. In one case, only fourteen visits separate two pictures.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1665–1667

Oil on canvas, 46.5 x 40 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1674

Oil on canvas, 51.7 x 45.2 cm.

National Gallery, London

The first six paintings constitute a relatively distinct group. The difference between the first three and last three paintings of this second group is marked. We might consider the first three as "Vermeer's most popular paintings" with certainty. In order of preference they are: The Girl with a Pearl Earring, The Milkmaid and the Dresden Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window. Owing to their iconic status, the positions of the first two come as no surprise.

A third group is composed of eight paintings each of which received less than ten thousand visits. The four "least popular" Vermeer's are A Lady Seated at a Virginal, Girl with a Flute, The Glass of Wine and A Lady Standing at a Virginal. One reason these pictures might rank low has little to do with their appeal and more with their placement on the page. Three of the four are among Vermeer's last paintings, located at the bottom of the index, making it less likely for visitors to scroll down and view them.. The lower position makes it less likely that the average visitor will scroll all the way to the bottom of the page before settling on one particularly eye-catching work. On the other hand, the colorful (and very "typical") Glass of Wine has received very few visits even though it is near the top of the catalogue list..

Other anomalies might be considered the famous Little Street, which is in position no. 19 and the iconic Lacemaker in position no. 21. Both works have been reproduced countless times in both popular and art history literature. Moreover, the Musée du Louvre boasts that their Lacemaker is its second most popular painting after Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa.

Although it has hardly drawn critical praise by experts, the recently attributed A Young Woman at the Virginals (New York private collection) stands at a healthy no. 25 while the wonderfully conserved (and signed) Guitar Player lags behind at a depressing no. 30. The placement of Saint Praxedis at position no. 24 might be due to its atypical style, leading visitors to question its attribution to Vermeer rather than its aesthetic appeal.