Dr. André Lehr,

who died on March 27, 2007 André Lehr, born in 1929 in Utrecht, had a distinguished career as a campanologist (bell expert). He started working at the Royal Eijsbouts bell foundry in Asten in 1949 and later became its director, serving until 1991. Lehr co-founded the National Carillon Museum in Asten in 1969, which was reopened in 1975 by Prince Bernhard. In 2004, he retired as the museum's head curator. Lehr's interests extended beyond bell technology and music; he was also passionate about their history, conducting extensive research and publishing numerous works. He received several honors, including the Knight of the Order of Orange-Nassau in 1982, an honorary doctorate from Utrecht University in 1986, and the Silver Carnation from Prince Bernhard in 1994. André Lehr passed away at the age of 77 on March 27, 2007, and was buried in the churchyard next to the Asten church.

Very few observers note that the sunlit spire of the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church) in Vermeer's View of Delft is depicted without a single bell. It is very probable that Vermeer depicted this passage shortly before the first twenty bells of the new carillon were hung on May 4, 1660, after the old bells had been taken down.Kees Kaldenbach, "The 'View of Delft' by Johannes Vermeer, a Guided Art History Tour, accessed November 27, 2023. But Vermeer must have had a deeper relationship with the art of the carillon long before and long after he completed the painting.

Like all of the approximately 20,000 inhabitants of Delft, carillon music accompanied every event of Vermeer's life. It must have also provided a melodic background for his daily painting sessions. In fact, Vermeer lived his entire life in the midst of bells. His youth was passed a mere stone's throw away from towering Nieuwe Kerk, first in Voldersgracht, then in his father's tavern Mechelen on the Markt. From about 1660 on, he lived with his ever-expanding family in the house of his mother-in-law Maria Thins at Oude Langendijk, just across from Mechelen. For the painter, it must have been impossible to escape the imposing sounds from the bells of the Delft city hall, those of the Nieuwe Kerk or of the Oude Kerk (Old Church) which had the Netherlands' largest bell, the Trinitas, or Bourdon-bell, 1570 cast by Hendrik van Trier.The "Trinitas" i weighs about 8.750 kg and has a diameter of about 230 cm.

(19th-century Italian saying).

In precisely the years of Vermeer's artistic activity, bell-founding and carillon-mounting had reached the peak of a first flourishing in the Netherlands thanks to the unsurpassed craftsmanship of the brothers François (1619–1680) and Pieter Hemony (c. 1609–1667) born of a noted family of bell founders in Lorraine. The carillon spread throughout the Low Countries stimulated by important technological developments in clock-making, general mechanics and metal working. Since the art of the carillon remains one of the most important facets of the Netherlands's cultural heritage and as it is the largest, heaviest, and perhaps most complicated of all musical instruments, it is worth a closer look at its history and amazing technical complexity. Then, returning to Delft, we will get acquainted with the Saint Ursula-Beiaard of the Nieuwe Kerk, Vermeer's daily musical escort.

Classification: The Bell

The Carillon

Dutch/Flemish: klokkenspel, beiaardFrench: carillon

German: Glockenspiel

Italian: cariglione

According to the Hornbostel-Sachs-system a bell (the principal part of a carillon) is an idiophone which creates sound primarily by vibrating itself when struck with a "tongue," known as the "clapper," suspended within the bell or with a separate mallet or hammer struck by the performer outside of the bell. Furthermore, the bell is classified as a percussion vessel. Certain types (e.g. pellet bells), however, are vessel rattles.

Since each separate note is produced by an individual bell, a carillon's musical range is determined by the number of bells it has. Different names are assigned to instruments based on the number of bells they contain. According to the definition of the World Carillon Federation, a carillon must possess at least twenty-three bronze bells, which, apart from the lowest three bells, must form a fully chromatic scale. Modern carillons encompass at least four chromatic octaves.

The Origins of Bells

Bells are among the oldest musical instruments of the world even though they were not primarily used for music making. They are typically made of metal (most often bronze, an alloy of circa twenty percent tin and seventy to eighty percent copper, even though we have evidence about bells made of stone, wood, hard fruit skins (e.g. coconuts) or special kinds of shells, often with teeth serving as clappers dating back to prehistoric times. Today, bells can be made of porcelainSee for instance the carillons in the Frauenkirche (Our Lady's Church) Meissen/Germany from 1929, the first well-tuned porcelain carillon world wide, or in the so-called Glockenspielpavillon in the Dresden Zwinger, both made of the famous Meissen porcelain. or even glass. Bells can vary in size, ranging from tiny dress accessories to church bells weighing thousands of kilograms.

c. 1520–1030 B.C.

Nationaal Beiaardmuseum Asten They were usually attached to

clothing or given as burial gifts.

The earliest known bronze bells were found in China, dating from the Shang Dynasty (c. 1520–c.1030 B.C.). They appeared mainly in two different types: with clappers, like the little ling, and without clappers, like the larger zhong from the Zhou Dynasty (1046 B.C.–256 B.C.) that at times reached the length of one meter. They were struck with a separate beater, and were normally constructed in tuned sets (bianzhong) mainly for ritual performances.

Early bells were used to protect animals from evil forces and to hold a flock together with its distinctive sound. They were also fastened onto clothing to impress both gods and men. Little golden bells were attached on the high priest's robe to chase away evil spirits. Confucius (551–479 B.C.) wrote that the heavens will use this great teacher as a "handbell with a golden tongue."To the research of large archeological finds of zhong-bells and their tuning see reviews by John Lienhard, "Ancient Chinese Bells," The Engines of our Ingenuity, University of Houston, (accessed November 27, 2023). For the history and art of ancient Chinese bells see André Lehr, Klokken en klokkenspelen in het oude China tijdens de Shang- en de Shou-dynastie (Asten, 1985). This same metaphor, with the bell as the preacher and the clapper as the tongue, was later also used in the Christian culture.

The oldest sources concerning the use of bells in Christian culture trace back initially to Egypt. With the Edict of Milan in 313 by Constantine the Great, Christians gained extensive religious freedom which enabled them to practice their faith with all its liturgical orders more openly. Some of the oldest bells known from early Christian culture appear to come from Byzantine cloisters in the area of Damascus. This suggests that that bells had been used at that time primarily in cloisters where they were cast by the monks themselves, mostly in the size of handbells. They were used to announce the canonical hours, calling the monks to the regular prayers. Hence the Latin name for the bell as signum—the signal.

The great significance attributed to the bell as a sacred implement is confirmed by the symbolism woven around it during the Middle Ages. With its hard, long-lasting material, and its far-reaching sound the bell came to symbolize the voice of the preachers of the New Testament: the voice would be heard until the end of time and in all corners of the Earth. Another example is the bell's consecration when it was first cleansed of wicked spirits, and afterward consecrated to the new service of preaching. In this ritual, the bell received a name usually relating to its function, like "Apostolica" for the Apostles' feasts, or "Dominica" for the normal use on Sundays. This ritual is still in use in modern times (with slight differences between the Catholic and the Protestant Church).

This person—a monk—is playing an automated kind of bell chime or a cymbala containing seven bells. They seem to be conveniently labeled [A, B,] C, D, E, F, G as it is noticed on the knobs.

With the expansion of Christianity across Europe and the construction of large churches featuring towers, originally designed for defense, the dimensions and acoustic properties of bells evolved significantly. As these churches grew in size, the bells increased in both size and volume, and their sound's prolonged decay became a distinctive characteristic of Western church bells—a feature that persists to this day. However, this evolution also meant a limitation in their rhythmic and melodic use. These larger bells were typically housed in the upper sections of church towers and, like their smaller handbell predecessors, were operated by swinging them with a rope.

In contrast to other types of bells, carillon bells are stationary, fixed to a metal frame. The clappers inside the bells move to strike the inner lip, producing sound, while the bells themselves remain immobile.

As cities grew during the Middle Ages, these bells took on roles beyond regulating religious life. They served a communal function, marking the hours for citizens. They also signaled various events: announcing the closing of town gates, proclamations from city halls, the death of notable individuals, and importantly for urban safety, alarms for fires or other dangers. To differentiate these diverse signals, each bell needed a distinct, recognizable timbre. Over time, as it became more common to ring multiple bells together for celebrations, there was a concerted effort to refine their tones to achieve a more harmonious sound.

During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, there was an increasing interest in using fragments of liturgical melodies for tower clocks in abbeys or mimicking them in the interplay of swinging bell peals. This required careful attention to the pitch relationship of the tower bells and significant improvements in their tuning. The evolution of clock chimes led to the widespread adoption of automatic playing systems and ultimately to the development of the carillon in the early sixteenth century. The earliest known carillon dates back to 1510 in Oudenaarde, Flanders. The concept of a carillon can be traced back to works like the "Cantigas de Santa Maria" by Alfonso the Wise from the late thirteenth century, which represent early predecessors of the carillon.

The Carillon

While swinging bells gained immense popularity in England and German-speaking regions, the carillon quickly established a significant presence in Flanders and the Netherlands, even though swinging bells hadn't yet become the dominant sound from Dutch towers. Carillons emerged as symbols of municipal pride, sparking a competitive spirit among cities and towns, each vying to own the most impressive instruments with the largest and finest bells. This ambition was not limited to major cities; even small hamlets strived to install a carillon. Typically housed in church or town hall towers, carillons were occasionally found in abbeys or palaces. Additionally, a number of bell towers were freestanding structures, known as campaniles.

However, with the definitive spread of the carillon in the sixteenth century, interest in swinging bells declined in the Low Countries. The case of the Delft swinging bells illustrates this fact. From the middle of the sixteenth century, their use diminished, with the last remaining ones being sold in 1808 (see part 5: The Swinging Bells and the "Saint Ursula-beiaard" of the Nieuwe Kerk in Delft).

The first well-tuned carillon, cast in 1644 by the Hemony brothers in collaboration with Jacob van Eyck, was part of the famous Zutphen carillon. It's housed in the Nationaal Beiaardmuseum Asten. The emergence of military artillery at the beginning of the fourteenth century led to the new profession of arms manufacturing. The original bronze casting facilities of bell founders were employed for both casting bells and cannons. The ironic effect of this development was that in times of war, the founders' business prospered through the need for cannons, while in times of peace, cannons made by melting down bells were in turn melted down to produce bells that could celebrate the victory the cannons had made possible.

During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Flemish and Dutch towns rivaled with one another in establishing the latest carillons. Most of the early carillons were cast in Mechelen (Flanders) by the famous bell founding families Waghevens and Van den Ghein. Some of these bells still exist, either in part (seven carillon bells in Sint-Leonardus church Zoutleeuw/Flemish Brabant, 1531 by Medardus Waghevens) or as a complete carillon (in the tower of Monnickendam, near Amsterdam, late sixteenth century, by Pieter Van den Ghein, still in use).

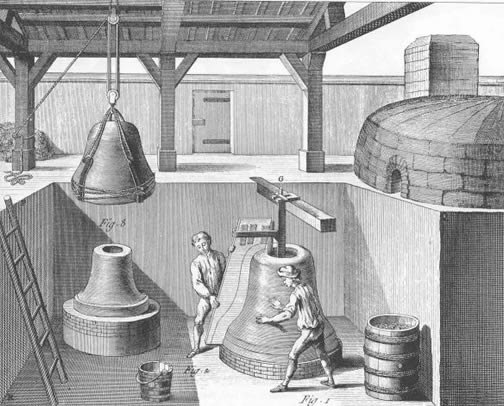

Bell founders did not work in fixed establishments. They moved their activity from town to town, even from country to country, casting bells near or directly at the place where they were to be hung due to the difficulty of transporting larger bells and the necessity of digging holes for the casting process. Thus, they were known as "itinerant" founders. The opportunity to inspect older bells before casting their own was one of the benefits of the itinerant system. Moreover, the knowledge gathered through continuous contact with local traditions was of great significance for research and improvement of bell founding and, essential for carillons, tuning..André Lehr, The Art of the Carillon in the Low Countries (Tielt: Lannoo, 1991), 10.

The practice of casting on-site did not entirely cease but in some cases continued into the nineteenth century. Casting ovens were even set up inside churches themselves, and records of bills submitted for repair work of the premises damaged during the casting operations still exist. Additionally, the introduction of hand-played music, rather than music produced by the automatic chiming system, placed constant pressure on founders to expand bell ranges. By the seventeenth century, it was possible to produce and tune sets up to three and one-half octaves.

The art of carillon playing originated five hundred years ago in the area of Europe that now comprises the Netherlands, Belgium, and northern France. It is there that the greatest concentration of carillons can still be found, with close to four hundred instruments in use. The intense interest in bells spurred technical progress. Bell makers sought the utmost perfection in tuning and timbre. The craft of bell making attained its highest status in the Netherlands, and the services of the Dutch founders were sought far and wide.

The Hemony Brothers

A decisive role in the development of the carillon was played by the brothers François (c. 1609–1667) and Pieter Hemony (1619–1680), born in Levécourt (Lorraine), sons of the church bell founder Peter Hemony or his brother Blaise. Initially, both worked independently before being commissioned to cast and deliver a carillon to the town of Zutphen in 1643 which, after extensive studies. The carillon they created brought the Hemony brothers to the forefront of carillon production in the Netherlands. They were based in Zutphen until 1657. Between 1657 and 1664 François ran a workshop in Amsterdam and became the inspector of bells and guns, while Pieter worked in Ghent. From 1664 to 1667, they worked again together in Amsterdam. After the death of François, Pieter continued to manage the workshop alone until his death in 1680. In all, they had produced fifty-one carillons, of which about thirty have survived, most of them only in part.Complete catalogue of all Hemony carillons in André Lehr, De klokkengieters François en Pieter Hemony (Asten, 1959).

Through painstaking research, the Hemony brothers became expert craftsmen and accomplished metallurgists. In order to improve bell tuning they sought the assistance of musicians capable of advising them on matters of timbre and especially the inner tuning of the bells. They found the most influential bell expert who they ever could wish for in Jonkheer Jacob van Eyck, the blind organist, carillonneur and recorder player, composer of the famous Der Fluyten Lust-Hof and director of the carillons in Utrecht.

After the famed French music theorist Marin Mersenne (1588–1648) discovered the overtones of a string, it was Jacob van Eyck who first understood how to systematically analyze the overtones of a bell. (For details about a bell's pitches and overtones see below "The shape and acoustics of a bell"). Van Eyck demonstrated his method with a wine glass by whistling at the pitch of the fundamental or one of the overtones of the glass, which would resonate at that tone if the whistled note conformed with one of those tones, began to resonate at that tone, thereby producing a sound. Constantijn Huygens, who was a distant cousin of Van Eyck, wrote about this experiment with great astonishment to his friends, the musician and music theorist Johan Albert Ban (1597/98–1644), and also to other learned gentlemen of that time, Mersenne, René Descartes (1596–1650) and Isaac Beeckman (1588–1637) became aware that Van Eyck was able to whistle all sorts of overtones out of a bell without even touching them. But while the scientists sought a physical explanation of this mysterious phenomenon Van Eyck put it to use by making a practical link to the comparison of the overtones which he had made sound individually. He came to the conclusion that by altering the bell's profile, their tones could be controlled. This was the first time in the history of bell founding that concrete and measurable information concerning bell notes was related to the measurements of the bell's profile.

The Hemony brothers likely came into contact with Van Eyck during their studies 1643 for the commissioned carillon in Zutphen, since Van Eyck was serving there as advisor for the municipality. Together they experimented with bell profiles and systems of tuning. Van Eyck established the best pattern of partial tones to constitute such a chord that would be heard as a unity at the moment the bell is struck. He termed this "tone" the slagtoon (the strike note which defines the pitch of the bell). The Hemonys appropriated Van Eyck's findings and developed from them a method of tuning. Consequently, they cast their bells somewhat thicker than necessary. Afterward, the bell was placed on a lathe and the correct sound was attained by removing material from the proper parts of the bell's interior surface. This method of bell-tuning has remained the most customary until the present day.

The Hemony brothers not only produced the most euphonious bells of their era but were also pioneers in creating chromatic carillons, extending their range to over three octaves. In doing so, they transformed the carillon into a fully-fledged musical instrument.

Regrettably, following the deaths of the Hemony brothers (with Pieter passing away in 1680), no one could match their excellence in bell founding and, particularly, in tuning. This includes their own pupils, with the possible exceptions of Claes Noorden and Melchior de Haze, who was likely a Hemony apprentice. The decline in quality may have been partly due to the Hemonys' secretive approach to their tuning techniques and the composition of their bronze, a practice common among founders and later dubbed the "bell-founders' secret." A few other founders, such as Melchior de Haze (1632–1697) from Antwerp, Andreas Frans van den Gheyn (1696–c. 1730) from Leuven, and Willem Witlockx (d. 1733), also from Antwerp, excelled in bell founding. However, their tuning skills were not on par with those of the Hemonys. The death of Witlockx in 1733, arguably the most prominent founder of his time, signified the end of the Golden Age in carillon history. Around the same period, other renowned founders like Alexius Jullien, Antoine Bernard, and Jan Albert de Grave also passed away. In the latter half of the eighteenth century, only Andreas Jozef van den Gheyn, from the distinguished Leuven bell founding family, created several notable carillons. These were lighter and higher in pitch than the Hemony creations. He was the last bell maker deeply versed in the art of tuning, and with his demise in 1793, this expertise was largely lost.

The French Revolution and subsequent Napoleonic occupation of Europe led to many carillons being repurposed for cannon casting. Moreover, the carillon's significance waned with the rise of bourgeois musical culture, which flourished in concert halls and private salons. The carillon's role in timekeeping was also eclipsed by the advent of indoor clocks and pocket watches. Despite these changes, the carillon never completely disappeared from daily life in Holland and Flanders. The traditional role of the municipal carillonneur was preserved in most towns, maintaining a connection to this historic instrument.

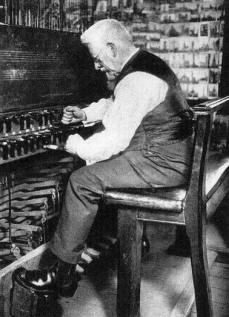

The Art of Carillon Playing

Traditionally, carillon performances were somewhat informal. In fact, these performances often included a significant element of improvisation, leading to a spontaneity that fostered a close rapport with the audience below. Given that the carillonneur plays from atop a tower, far removed from the public, the performer must captivate the listeners' attention by infusing their music with imagination and dramatic qualities.

At the end of the nineteenth century, two influential figures made significant contributions to the revival of carillon art. The first was Jef Denyn (1862–1941), who served as the municipal carillonneur at Saint Rombouts in Mechelen starting in 1887. Denyn was known for his magnetic personality, exceptional musical sensitivity, and impressive physical dexterity. He made notable improvements to the mechanics of the carillon, enhancing playability (for more details, see below in Part 2, "The Structure and Technique of a Carillon"). Additionally, Denyn pioneered a new, highly virtuosic and subtle musical style known as the "Flemish Style." This style brought him immense success during his weekly recitals and inspired carillonneurs worldwide. In 1922, following World War I, Denyn's vision for professional carillonneur training materialized with the establishment of a "beiaardschool" in Mechelen. This institution, the first of its kind in carillon history and now globally recognized as the Koninklijke Beiaardschool "Jef Denyn," became a hub for young carillonneurs. Denyn's reputation drew numerous international students to the school, solidifying its status as the epicenter of carillon art.

The second key figure instrumental in the resurgence of the carillon was Canon Arthur B. Simpson, an English clergyman with a keen interest in church bells who found the state of bells in England unsatisfactory. In 1896, after extensive research on English and continental bells, including several by Hemony, Simpson rediscovered the lost art of tuning the five principal partials of a bell, a significant advancement from the then-common practice of tuning only one partial. English bell foundries, John Taylor & Co. and later Gillett & Johnston, embraced Simpson’s innovations and developed the expertise to tune a chromatic series of carillon bells, achieving excellent quality.

World War II saw the destruction or requisitioning of many carillons. However, this period also saw some bells become accessible for scientific research. The findings from these studies enabled the Dutch bell founders Eijsbouts in Asten and Petit & Fritsen in Aarle-Rixtel—both now renowned foundries to produce finely tuned carillons. They were also able to create bells in the precise "Hemony-style" to replace historic bells that had become out of tune due to corrosion from air pollution.

The enduring and vibrant interest in carillon art is evident in various initiatives. These include the establishment of the "Nederlandse Beiaardschool" in Amersfoort in 1953, the extensive efforts of numerous national and regional carillon associations in the Netherlands and Belgium, and events such as festivals and competitions in carillon playing, notably the International Queen Fabiola Competition in Mechelen, or the establishment of two carillon museums in Asten (1969) and Mechelen (1985).

TThe Royal Carillon School, established in 1922 by the celebrated city carillonneur of Mechelen, Jef Denyn, was later named in his honor. It was founded with the backing of prominent Americans such as Herbert Hoover, John D. Rockefeller, and William Gorham Rice. As the first institution dedicated to this musical art, the school quickly earned international recognition. It has since educated carillonneurs from a wide array of countries, including but not limited to Canada, China, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Ghana, Japan, New Zealand, Portugal, Russia, Switzerland, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, showcasing its global impact and significance in the realm of carillon music.