While the traditional carillon keyboard bears some resemblance to other keyboard instruments, its playing technique is distinctly unique. The carillon is played using a keyboard known as a baton keyboard or stokkenklavier. Similar to a piano, it features shorter chromatic keys positioned above the larger diatonic ones. However, unlike a piano, the carillon's keys are wooden levers with rounded ends for playing. These keys are pressed using the carillonneur's closed fists.

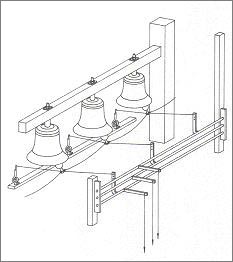

Additionally, the carillon typically includes one to two octaves of pedal keys, akin to those found on an organ, which are used to play the heavier bass bells with the feet. Engaging these pedal keys simultaneously pulls down the corresponding manual keys above. Each key is connected to a bell via a system of wires.

Despite the use of a closed fist, carillonneurs do not "pound" or "beat" the keys. Instead, the playing action is designed to be sensitive enough to require minimal effort, allowing the carillonneur to control dynamics and phrasing through variations in touch. This nuanced approach to playing is crucial for the expressiveness and musicality of carillon performance.

The measurements of the breech-system must be meticulously calculated. For precise playing, it is essential to position the keyboard near the bells, thereby minimizing the length of the mechanical connections. Each key is equipped with an adjuster above the keyboard. This adjuster enables the performer to counterbalance the effects of expansion and contraction in each metal wire, which result from variations in air temperature.

: Joos Verschuere Reynvaan, Muzijkaal Kunst-Woordenboek Amsterdam, 1795.

The entire mechanical system of the carillon was constructed by carillon makers, distinct from the bell founders. Their craftsmanship was crucial for achieving a harmonious overall sound in the carillon and ensuring comfortable playability. The proper connection of the clappers to the keyboard involved meticulous "trimming" to ensure the optimal functioning of the system. Additionally, this included the connection of the hammers to the drum for the automatic chiming mechanism. Consequently, the most adept carillon makers of the time were highly esteemed for their specialized expertise in this intricate field.

Among the most renowned carillon makers of the seventeenth century were Juriaan Sprakel in Zutphen, known for fitting the Hemony carillon in the Dom tower of Utrecht in 1664, and his cousin Willem, as well as Jan van Call in Nijmegen, who installed the automatic chiming system in the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church) in Delft. However, the preeminent authority in all matters related to the carillon was Jacob van Eyck (c. 1590–1657). He inspected and fitted several carillons, though his blindness necessitated the assistance of colleagues and skilled craftsmen.

To the left of the diagram is a representation of a bell connected to a bell-crank or tumbler (shown on the right side). The downward motion of the key (illustrated above) is converted into a lateral movement by the tumbler, positioned at right angles. This action causes the clapper to be pulled towards the sound bow, resulting in the striking of the bell. On the left side, the return spring repositions the clapper to its original place immediately following the stroke.

It is evident that playing carillons in the early seventeenth century posed significant challenges, requiring considerable physical strength. This often hindered carillonneurs from fully focusing on the dynamics and finer nuances of their performance. Records from that era frequently mention complaints about the heavy action of the keyboard in reports on newly installed carillons. These issues eventually led to advancements, primarily in the trimming and fine-tuning of the system.

It took over two centuries, following a gradual decline in the art of carillon and a loss of bell tuning skills, before substantial improvements in playability could be achieved. Joseph Guillaume François (Jef) Denyn (1862–1941), who became the municipal carillonneur at Saint Rombouts in Mechelen in 1887, recognized the necessity of first enhancing the instrument itself. He aimed to make the interaction between the keyboard and the bells both quicker and more responsive. This endeavor necessitated significant modifications to the mechanical system, particularly in the innovative use of "tuimels" or "tumblers."

An additional advancement involved the implementation of return springs for the clappers, usually in the form of coiled leaf springs. These springs ensure that the clapper disengages from the bell immediately after striking, allowing the bell to resonate freely.

Jef Denyn’s full name was Joseph Guillaume François Denyn. He was born in Mechelen in 1862 and died there in 1941. His father, Pierre-Antoine-Adolphe Denyn, was city carillonneur (stadsbeiaardier) of Mechelen; when the father went blind, Jef stepped in to play the city carillon from 1881, and in 1887 he was formally appointed to his father’s post. He had originally trained as an engineer, and that background becomes crucial for his later technical work.

As a performer and public figure, Denyn is often credited with rescuing the carillon tradition from decline. In the late 19th century many Low Countries carillons were in poor condition and were thought of more as quaint clockworks than serious musical instruments. In Mechelen, Denyn began giving evening concerts (particularly Monday night concerts) that drew large crowds and turned the tower performances into regular civic events between roughly 1900 and 1930.([bellfriends.fuga.se][3]) He toured widely in Belgium and abroad as an adviser on carillon construction and restoration, and his popularity was such that his 25th anniversary as city carillonneur in 1912 became a public celebration; a new "jubilee bell"was dedicated to him with the inscription aan den grooten beiaardier Jef Denyn, het bewonderend volk ("to the great carillonneur Jef Denyn, from the admiring people"). The Belgian king made him a knight of the Order of Leopold, and contemporary photos show him posing among the massive action frames and bells of the Sint-Rombouts tower in Mechelen, very much presented as a modern master of a complex machine.

Technically and institutionally, his impact is even greater. Drawing on his engineering training, Denyn revised the mechanical transmission systems of carillons, seeking a more responsive touch and better dynamic control. Those improvements informed restorations and new carillons across Europe and the United States and helped shift the carillon from a semi-automatic civic device into a fully expressive concert instrument. In 1922 he founded in Mechelen what is generally regarded as the world’s first dedicated carillon school, later named the Royal Carillon School "Jef Denyn". American donors, including Herbert Hoover, John D. Rockefeller, and carillon enthusiast William Gorham Rice, helped finance it; the school rapidly became the international center for carillon studies and performance, training a large share of the 20th-century carillon players and developing what is known as the Flemish romantic style of carillon playing and composition.

His life was also shaped by the First World War. During the German invasion and occupation of Belgium, Denyn and his family fled as refugees to England, where they were taken in by the organist and musicologist William Wooding Starmer in Tunbridge Wells. This exile period helped further internationalize his reputation and the prestige of the Mechelen carillon tradition. Back home after the war, he continued to compose for carillon and direct the school. Modern reference works on Flemish music describe him as a Mechelen city carillonneur, composer, and co-founder/director of the international carillon school, viewing him as a central figure in the Flemish musical movement.

Beyond facilitating more sensitive play, the return springs also allow for rapid repetition of a single note, creating the tremolando effect. This technique is especially useful for extending the shorter frequencies of the smaller "treble" bells in an artistically pleasing way. The tremolando became a hallmark of Denyn's revolutionary "Flemish style," characterized by its stark contrasts, virtuosic passages, and free yet impeccably controlled rhythms. This style introduced a new form of "romanticism" in carillon-playing, previously unseen in the field.

Different Opinions about the Styles: The "Broekse en Tuimelaarse Twisten" (Breech and Bell-Crank Disputes).

The introduction of the new Flemish style in carillon playing, spearheaded by Denyn, was not universally embraced. This led to the "Broekse en Tuimelaarse Twisten" (breech and bell-crank disputes), serious debates revolving around technical and stylistic aspects of carillon music. These discussions were particularly animated when certain Dutch associations and municipalities, such as Arnhem and Utrecht, sought Denyn's advice on transitioning their carillons from the old "broek," or breech system, to the newer "tuimelaar," or bell-crank system.

Beyond the differences in mechanical systems, there was also a divide in the type of pedal systems used. The Flemish pedal, positioned in front of the player, enabled forceful yet controlled playing. Conversely, the Dutch pedal system, with pedals hinging underneath the player's bench akin to a traditional organ, was criticized for being slow and cumbersome.

Despite the perceived disadvantages of the old Dutch system, proponents of the traditional playing technique, eschewing modern embellishments, persisted. The most notable advocate of the conventional Dutch style was Jacob Vincent (1868–1953), who served as the carillonneur at the Royal Palace in Amsterdam from 1900 to 1952. Throughout his life, Vincent steadfastly adhered to the traditional style, achieving remarkable success, particularly in his evening concerts which began in 1909, shortly after the birth of Princess Juliana, who later became Queen.

The two distinct systems and styles in carillon music reflect contrasting cultural orientations: the more reserved and somewhat rigid Calvinist North versus the expressive and playful Catholic South. The two most renowned carillonneurs of the time, the quintessential Dutchman Jacob Vincent and Jef Denyn, embodied the respective sides of this divide. Notably, they were never able to forge a harmonious relationship.

Despite having all the components for a playable and melodious carillon, the Utrecht municipality was reluctant to implement Denyn's recommendations for installing a bell-crank system in the Dom tower. This led to fervent debates over techniques, styles, and traditions, humorously referred to as the "broekse en tuimelaarse twisten" ("breech and bell-crank disputes"). This term humorously echoed a civil war from the late fourteenth/fifteenth century, known as the Hoekse en Kabeljauwse twisten. The dispute persisted for years, but as more Dutch carillon towers gradually transitioned from the old broek-system to the modern tuimelaar-system, the contention eventually subsided.See also André Lehr, The Art of the Carillon in the Low Countries (Tielt: Lannoo Printers & Publishers, 1991), 242, note 248. The dispute continued for years, but with the gradual passage from the old broek-system to the modern tuimelaar-system in most of the Dutch carillon towers, it slowly faded away.