The Musette de cour – An Instrument of Fashion at the French Royal Court

The musette,The enormous popularity of the musette in its time became also evident in a dance of a somewhat languid, fragile character that bears the same name as well as dance-like pieces of pastoral character whose style is suggestive of the sound of the musette: the bass part generally has a drone (bourdon) and the upper voice or voices consist of the melodies. During the 19th century the musette (as a music piece) changed from "art music" to a popular waltz of the "light music," often played on the accordion and performed in many of those etablissements frequented by the French bohemiens. Opera-goers may remember Musetta's well-known "waltz" (her song vQuando me'n vov) in Act II of Giacomo Puccini's La Bohème (1896). as it is still known today, consists of a leather bag covered with costly materials,Velvet, brocade, silk, often decorated with pearls and artful embroidery were used for this purpose. a bellow for the air supply, two chanters, French called petit-chalumeau and grand chalumeau with keys made of silver, and a characteristic shuttle-drone, frequently made of ebony and ivory (fig. 1).

The early, simplest form of the musette was known as musette de Poitou (similar to the German "Hümmelchenv) and in the sixteenth century was used in the vmusique militairev at the French court of François I, for celebrations, anniversaries of military victories, triumphal royal entries etc. But it was also played for outdoor entertainment staged in the woods, gardens or on the water.

Michael Praetorius was among the first who described a "small bagpipe…, in which the wind is produced solely by a small arm-operated bellow." In a drawing he places this somewhat curious instrument aside the crumhorns indicating that he thought the instrument did not belong to the same category as the bagpipes.

Hyathinthe Rigaud

The rich decoration of the bag's covering as well as the use of ebony and ivory for the shuttle-drone and the chanters are clearly visible.

Marin Mersenne (1588–1648) shows in his Harmonie Universelle (1636) a single chanter musette with a bellow, a shuttle-drone for the bourdon notes and a covered leather bag with fringe (fig. 2).

A plate in Charles-Emmanuel Borjon de Scellery's Traité de la musette (1672) illustrates (fig. 3) a developed system of a petit chalumeau with a physically connected grand chalumeau, sharing the same wind-supply from the bellow. Borjon raccounts that the petit chalumeau was the "triumph" of the renowned wind instrument maker Martin Hotteterre (1640–1712) and that all pastoral and rustic representations as well as the King's Ballet cannot do without the musette. It was only sixty-five years later that Jacques-Martin Hotteterre mentioned in his Methode pour la musette (1737) that the addition of the petit chalumeau was the work of his father Martin.

The form of the musette's shuttle-drone for the bourdon notes is unique for a bagpipe. It follows the principle of the Renaissance rackett with four to five cylindrical air-ways bored through the wooden block. Openings in each air-way (the equivalent of the finger holes in the rackett) are uncovered by moving layettes (sliders) fixed in coulisses (grooves). Each air-way is equipped with a double reed, and the air from the bag enters via the reeds, passes through the tunnels and out through the portions of the slits on the side of the block which are not covered by the sliders. This makes producing four to five tones at the same time possible.

This kind of drone could be set to play in a variety of different keys, (normally C, G, D, A, B flat and F) which suited the common setting of the other instruments played together, particularly the hurdy-gurdy. However, the drone setting of the musette must be well tuned to the tonality of the chanter.

For details to the playing-technique of the musette see the very informative website Musette de cour (section "Execution").

Jean-Antoine Watteau

c. 1717–19

Oil on canvas, 56 x 81 cm.

Staatliche Museen, Schloß Charlottenburg, Berlin

One of Watteau's numerous depictions of the Amusements Champêtres held by the French nobility. The man sitting under the tree is playing the musette to the dance of the young couple.

As we already know from the hurdy-gurdy, the newly developed interest in the ancient Arcadian ideal at the Royal court of Louis XIV and Louis XV in particular culminated in ingenious outdoor events, the so-called Fêtes Champêtres (pastoral festivals) (fig. 4), where the courtiers fantisized that the shepherds in the ancient Arcadia used to play the musette. Through song and dance the participants attempted to recreate their own little slice of Arcadia. Because in the seventeenth century the bagpipe was considered to be the instrument of the country folk used for their feasts, weddings and other types of recreation, French courtiers felt that the bagpipes were uncouth, which led to the exchange of the former blowpipe with the arm-operated bellow for the air supply,The other bagpipe, which utilizes the system of the arm-operated bellow for the air supply is the Irish union pipe or uilleann pipe (uilleann in Gaelic literally means "elbow," perhaps referring to the use of the elbow to compress the bellow). Together with the ancient harp it is Irelands national music instrument, producing a far more delicate sound than that of the Scottish Great Highland bagpipe. For details see "Uilleann pipes." http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uilleann_pipes to avoid grimacing and puffed cheeks.

Click here for period bagpipe music:

Highland bagpipe marches,

performed by young girl piper Alison Dunsire on the Great Highland bagpipe.

In the second half of the seventeenth century, these popular pastoral scenes were imported into ballets and operas, and the musette also began to be employed in the Royal orchestra. This led to the musette's increasing popularity in the 18th century amongst amateur musicians from the upper class. Jacques-Martin Hotteterre as well as the renowned composer, musette player and maker Nicolas Chédeville, the luthier Henry Bâton, Joseph Bodin de Boismortier or the famous Jean-Philippe Rameau wrote numerous compositions for the musette, from simple transcriptions of dances or popular tunes to demanding pieces for ensemble music or for the Royal orchestra. Not even the recorder or violin had inspired such an enormous amount of compositions.

Anthony van Dyck

Early 1630s

Oil on canvas, 97.8 x 80 cm.

National Gallery, London

One of the few contemporary paintings of a musette player is Anthony van Dyck's informal portrait of his friend François Langlois, an engraver, art dealer and publisher who acquired works of art for king Charles I of England and other English collectors. Langlois is known to have been an accomplished amateur musician, in particular for playing the musette. Van Dyck painted him dressed as a Savoyard or itinerant shepherd (fig. 5), according to the "Arcadian' fashion of that time.

The musette's ultimate fate was similar to that of the hurdy-gurdy. With the French Revolution it fell rapidly out of favor amongst the nobility while simpler forms of bagpipe remained popular as folk instruments. Only "he "authentic performance" movement from the 1970s onward made it possible to hear today works of chamber-music, for instance by Boismortier, in their original form.

The structure, tuning and playing technique of the bagpipe

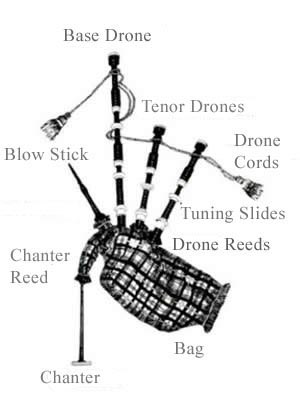

To understand its structure and playing technique, it will help to look closer to the Great Highland bagpipe (fig. 6), Scotland's national instrument, well-known all over the world and certainly the queen of all bagpipes.

The addition of the second drone around the end of the fifteenth century marked by far the end in the development of the bagpipe. It is impossible to say with certainty when exactly the third drone—the "bass" drone as it produces a pitch one octave below that of the other two "tenor" drones—had been added. Considering various sources we can be reasonably sure that if the three-drone bagpipe did not exist before 1600 it was invented not much after.

The "heart" of the bagpipe is undoubtedly its bag, usually made of the skins of local animals such as goats, sheep, cows or pigs. More recently, bagpipe makers have experimented with modern materials such as rubber, Gore-Tex or other airtight fabrics, but pipers with a feeling for tradition prefer natural materials. In former times, the bags were made from largely intact animal skins, and the stocks were typically tied into the points where limbs and the head joined the body of the living animal. Today, the bags are mostly cut from larger pieces of leather. The bag of the Great Highland bagpipe is enclosed within a decorative cover.

The piper fills the bag with air by means of the blowpipe or blowstick, attached to the bag. A one-way valve inside the blowpipe prevent the air from flowing back out while the piper inhales. The air from the bag flows through the chanter and the drones, creating sound as it passes through the reeds. The piper has to refill the bag continuously which requires an enormous amount of physical endurance.

The melody is produced entirely by the chanter which can be bored either conical or parallel and normally operates with a powerful double reed, placed inside the pipe. All bagpipe reeds are made of cane, preferably from the species arundo donax. The piper holds the chanter vertically and covers or uncovers the holes with the fingers to produce the desired notes. There are eight holes on the chanter but nine notes to play (from G0 to A1). The highly intricate finger movements acquire a great amount of technique and manual dexterity. Some modern chanters have additional keys (similar to those of the musette) to extend the range and number of accidentals the chanter can play.

As already mentioned, the Great Highland bagpipe has three drones: two identical tenor drones (to increase the volume of the pipe) and a larger bass drone. Together they are responsible for the constant "humming" sound. The drones are traditionally made of wood, either from local hardwood, or (particularly nowadays) from tropical hardwoods, such as rosewood, ebony or African Blackwood. They are generally designed in two or more parts, with tuning slides (partly ornamented with silver or ivory) to manipulate the pitch of the drone by shortening or elongating its length. Contrary to the chanter, the drones have usually single reeds, which are inserted into the base of the drone, between the bag and the drone itself (see graphic vDrone Reeds"), acting as airflow valve to allow air to be pushed through into the body of the drone, producing the low humming sound. The A of the tenor drone sounds one octave below the low A of the chanter, and the bass drone is tuned again one octave below the tenor drone.

Today, the bagpipe's tuning problem is that during the last century the pitch did not remain the same through time but crept higher and higher so that an A in normal concert pitch of 440 Hz is now between c. 470 and 485 Hz at the bagpipe. But since bagpipes are usually solo instruments, the consequences of being out-of-tune with other instruments are minimal. It is essential that the drones are in tune both with one another and with the chanter as the correct interplay between the melody notes sounding against the steady tones of the drones reinforces one another in a complex, even dramatic way and thus creates the bagpipe's typical sound. Naturally, if the bagpipe is played in a band, they must be tuned to each other.

The drone cords are not only decorative accessories but allow the drones to hang a certain distance apart from each other, while staying together.

It has already been mentioned that playing a bagpipe (and the Great Highland bagpipe in particular) requires considerable physical power, particularly of the lungs, as well as a special development of the muscles around the mouth (called embouchure by trumpeters or flutists). Physical strength can be gained by playing at first with a practice chanter or a beginner's bagpipe, called "goose," a bagpipe without drones which needs less air.

During the playing, the piper furnishes a constant air flow and pressure by blowing air into the bag via the blowpipe at the same time balancing the pressure applied by the player's arm against the bag. An even air flow is necessary to keep the pitch of the various pipes at a constant level, otherwise the bagpipe would go out of tune. On the other hand, this means that the open-ended chanter always produces sound and that there can be no rests or momentary pauses between notes, and the volume of the notes cannot be varied. To some extent these problems can be overcome by embellishments or grace notes to break up notes and to create the illusion of articulation and accents. Such ornaments are highly technical systems specific to each bagpipe and take much practice to master, especially when available notes require awkward finger positions, like half-covered holes. But apart from their primary function to separate single notes and together with a certain timing for a more expressive type of music, the grace notes add color and character to the music.

The Bagpipe Today

Bagpipes today are probably as popular as they have ever been in history, especially, of course, on the British Isles. Traditionally, one of the main purposes of the bagpipe was to provide music for dancing. However, with the huge number of pipers in the Highland regiments of the British Army, trained for two World Wars in the 20th century, the Great Highland Bagpipe was spread over the world which led to a decline in the popularity of many traditional forms of bagpipe throughout Europe. But, similar to other traditional instruments, by the revival of native folk Music and Dance during the 1960s many types of bagpipes have resurged in popularity, not the least thanks to the deep interest and enthusiasm of numerous instrument makers, teachers and professional players.

In the Netherlands the great tradition of bagpipe playing is cultivated by many traditional folk music groups (fig. 8) and has remained as lively as ever.

Their main bagpipe event is without doubt the "InterNationale Doedeldag" (The Dutch Annual Bagpiper's Day), an important meeting point for Dutch/Flemish as well as for international bagpipe players, makers and enthusiasts.

This Scottish tradition is maintained by many pipe bands and individual pipers, frequently with their roots on the British Isles. Most of them are organized in the Nederlandse Organisatie van Doedelzakbands (The Netherlands Pipe Band Association) (fig. 7) which arranges a great number of national and international meetings and competitions.

De InterNationale Doedeldag / The Dutch Annual Bagpiper's Day

Nederlandse Organisatie van Doedelzakbands / The Netherlands Pipe Band Association

An extensive demonstration of playing the hurdy-gurdy, together with the bagpipe and the musette, the recorder and crumhorn can be experienced in a video created by the Thornton School of Music at the University of Southern California. It is a c. 45 min. live recording of an event entitled "Demonstration of rare instruments." The real demonstration, with detailed information to all employed instruments (with the emphasis of the hurdy-gurdy), executed by two knowledgeable professional musicians, begins after some introductory words by the manager. "Browsing" through the video is possible (at least when using Windows media player) by dragging the running search bar at the bottom of the player to the right or left.

Bagpipe resources:

- Francis Collinson, The Bagpipe. The History of a Musical Instrument. London: Routledge Kegan & Paul, 1975.

- Grove Music Online: https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic

- entry "Bagpipe" - William Cocks / Anthony C. Baines / Roderick D. Cannon

- entry "Musette" - Robert A. Green/ Anthony C. Baines / Meredith Ellis Little

The bagpipe on the web:

- website - The Universe of Bagpipes

- website - Musette de cour

- website - Bagpipe iconography

- Frans Hattink doedelzakbouwer - bagpipe maker