In order to ensure the highest degree of geometrical precision and visual clarity, the two sets of perspective diagrams provided below were devised using high-resolution images of Vermeer's paintings and a scalable vector-based graphics (SVG) application (Inkscape). This format allows greater precision than raster-based applications such as Painter, Photoshop or GIMP. In order to speed download time, the SVG images were sized down and transformed to PNG, and then in the internet-friendly JPEG. The SVG images can be obtained upon request, free of charge.

The diagrams were created with a common procedure loosely referred to as reverse perspective (not to be confused with a primitive form of perspective), or reverse geometry, in which the visual evidence embedded in the painted surface is utilized to retrieve hypothetical vanishing lines, vanishing points and horizon lines rather than, as an artist himself would have done, to create the positions and foreshortening of the objects by means of these elements. The reconstructions are, naturally, based on the assumption that Vermeer's pictures obey the rules of linear perspective.

By examining the evidence presented in the painted surface of Vermeer's pictures, what can we deduce about his knowledge of perspective and the method(s) he may used to achieve his results? First of all, not all Vermeer's perspectives are equal in degree of sophistication or precision. There are three or four paintings whose perspective crudeness suggest that linear perspective was not employed. There are 10 or so that can be created with one-point perspective alone, and another 10 that demand knowledge of both one-and two-point perspective.

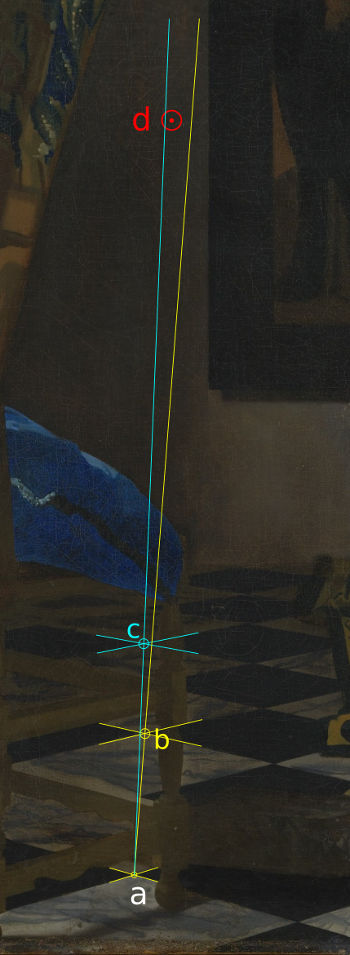

(detail showing the intersection of the orthogonals and the location of the pinhole vanishing point [in red])

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1657–1661

Oil on canvas, 45.5 x 41 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

One-Point Perspective

The fact that the orthogonals of Vermeer's one-point perspectives do not intersect precisely at the central vanishing point (fig. 1) but are dispersed over a relatively discreet area—whose range varies from painting to painting—does not necessarily indicate a lack of systematic understanding of the laws of linear perspective on the part of the artist. Dispersion occurs even in those paintings that present a pin-point hole in the canvas. Since as far as we know the sole function of the pin hole was to act as a fixed vanishing point by which orthogonals could be mechanically and consistently measured with a sting or straight-edge tool, it is likely in these cases that the lack of geometrical coherence can be traced to variables pertaining to the painting process or methodology.

Although not generally highlighted by those who aspire to reconstruct the perspective armature of centuries-old paintings, the retrieval and subsequent interpretation of perspective elements from a painted surface is fraught with hazard. Absolute precision is not attainable, if for nothing else, the difficulties of interpreting the often ambiguous visual information of the paintings. Even the slightest misinterpretation of the angle of a painted segment will cause a fully projected vanishing line to stray from its theoretical vanishing point, sometimes dramatically so.

In various paintings by Vermeer the straight edges of architectural features or movable objects are sometimes lengthy enough to provide a relatively secure basis for projection, such as the edge where a tiled floor meets a side wall (see The Music Lesson). On the other hand, many segments are so short that mismeasurement is practically guaranteed, such as those of the braces of chairs or the edges of a foot stool, or, even smaller, those of a foot warmer (see The Milkmaid ). This is why diagrams of Vermeer's perspectives, in which subjectivity cannot be avoided, vary from author to author. Many authors choose simply to ignore any discrepancies in favor of a theoretically correct rendering, assuming that Vermeer's perspectives are by definition geometrically sound and highly accurate. Hopefully, the diagram (fig. 2) of Vermeer's Allegory of Faith, a relatively carefully painted work, illustrates the point set out above.

fig. 2 Allegory of Faith (detail)

fig. 2 Allegory of Faith (detail) Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1674

Oil on canvas, 114.3 x 88.9 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Points "a," "b" and "c" are located precisely at the points where the upper and lower corners of a receding row of white floor tiles touch each other on the painted surface. These points should fall on a single line. However, it becomes evident that when point "a" is connected to point "b" it produces a line (yellow) that passes to the right of the vanishing point, which is described by a small red dot inside a larger red circle at area "d." The vanishing point in this case can be securely located by the presence of a pin hole that was presumably made by the painter himself. Similarly, when a line is projected from point "a" through point "c" it passes slightly to the left of the pin hole. At the height of the central vanishing point the distance between the two orthogonals can be easily noted.

Two-Point Perspective

Two-point, or distance-point, construction is applied to objects rotated 45 degrees to the viewer's line of sight, be they flat, such as diagonally set floor tiles, or three-dimensional (e.g., foreground chairs of the Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid or Allegory of Faith). In Vermeer's perspectives both the locations of the distance points and their relative vanishing lines are generally less precisely contrived than those of the orthogonals notwithstanding the fact that it would have been possible to attain a similar level of accuracy by means of the same workshop procedure (pin-and-string) used for one-point construction, had, of course, perspectival accuracy been of overriding importance. In fact, since the slight, localized changes in the angle that inevitably occur during the painting process do not alter even minimally the reading of spatial depth by the observer, and become noticeable only when they are projected, the painter would have had little incentive pursue precision for its own sake. In fact, there are few instances in Vermeer's paintings in which the consequences of minor geometric imprecision lead to the awareness that something has gone awry. One example is the near isometric projection of lower braces of the chair on which the male lute player is seated in The Concert (fig. 3).

fig. 3 The Concert (detail)

fig. 3 The Concert (detail)Johannes Vermeer

c. 1663–1666

Oil on canvas, 72.5 x 64.7 cm.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

For a complete list of pre-1900 perspective manuals (with subsequent republishings) consult the Russell Light's excellent PERSPECTIVE RESOURCES, from which the list below was derived.

Click on the links below to access PDF files of the treastises.

- ALBERTI, Leon (1435) - De Pictura.

* Italian translation - Della Pittura, 1436. First published editions: Latin - Basel, 1540; Italian - Venice, 1547; English (trans. from Italian) - Leoni, 1726. - FILARETI (c.1461–1464) - Libro Architettonico, (later referred to as the Trattato…)

- P. DELLA FRANCESCA (c.1470) - De Prospectiva Pingendi, critical edition ed. G Nicco-Fasola, Florence, 1942.

- DA VINCI (c. 1500–1518) - Notebooks

- VIATOR (Pèlerin, Jean) (23 June, 1505) - De Artificiali P(er)spectiva, Toul, Petrus Jacobi.

- DÜRER, Albrecht (1525) - Unterweisung in der Messung mit Zirkel und Richtscheit (Measurement by Compass and Ruler).

- SERLIO, Sebastiano (1537–1547) - Tutte l'Opera d'Architectura et Prospettiva, Venice.

- ARETINO, Pietro (1557) - Dialogo della Pittura di M. Lodovico Dolce initolato l'Aretino, Venice.

- COUSIN, Jean (1560) - Livre de Perspective, Paris, Jean le Royer.

- BARTOLI, Cosimo (1564) - Del Modo di Misurare le Distantie, le Superficie, i Corpi, le Piante, le Provincie, le Prospettiue, & Tutte le Altre Cose Terrene, Venice, Francesco Franceschi.

- BARBARO, Daniele (1568) - La Practica della Perspettiva di Monsignor Daniele Barbaro Eletto Patriarca d'Aquileia, Opera Molto Utile a Pittori, a Scultori, & ad Architetti, Venice, Camillo and Rutilio Borgominieri.

- JAMITZER, Wenzel (1568) - Perspectiva Corporum Regularium, Nurnberg, Gotlicher Hulff.

- BASSI, Martini (1572) - Dispareri in Materia d'Architettura, et Perspettiva. Con Pareri di Eccellenti, et Famosi Architetti, chi li Risoluono, Brescia, Francesco and Pietro Maria Marchetti.

- DU CERCEAU THE ELDER, Jacques Androuet (1576) - Leçons de Perspective Positive, Paris, Mamert Patisson.

- VIGNOLA, Jacopo Barozzi da (1583) - La Due Regole della Prospettiva di M. Iacomo Barozzi da Vignola con i Comentarij del R.P.M. Egnatio Danti, Rome.

- VILLAFANE, Ioan de Arphe y (1585) - De Varia Commensuracion para la Escultura, y Arquitectura, Seville, Andrea Pescioni y Ivan de Leon.

- SIRIGATTI, Lorenzo (28 October, 1596) - La Practica di Prospettiva, Venice, Girolamo Franceschi. (Eng. ed., Issac Ware, 1756)

- DEL MONTE, Guido Ubaldo (1600) - Perspectivae Libri Sex, Pesaro, Hieronymus Concordia.

- DE VRIES, Hans Vredeman (1604–1605) - Perspectiva, id est Celeberrima ars Inspicientis aut Transpicientis Oculorum Aciei, in Pariete, Tabula aut Tela Depicta, The Hague, Leyden.

- HONDIUS, Hendrik (1622) - Onderwysinge in de Perspective Conste, The Hague, Hondius.

* (1622) - Institutio Artis Perspectivae.

* (1625) - Instruction en la Science de Perspective.

* (1640) - Gondige Onderrichtinge in de Optica, oft Perspective Konst, Amsterdam. - ACCOLTI, Pietro (1625) - Lo Inganno de Gl'ochi, Prospettiva Practica, Florence, Pietro Cecconcelli.

- VAULEZARD, I.L. de (1630) - Perspective Cilindrique et Conique; ou Traité des Apparences Vues par le Moyen des Miroirs Cilindrique et Conique, Paris, J. Jacquin.

- DESARGUES, Girard (1636) - Example d'une des Manières Universelles, Paris, the author.

- NICERON, Jean François (1638) - La Perspective Curieuse, ou Magie Artificielle des Effets Merveilleux de l'Optique…la Catoprique…la Dioptique, Paris, Pierre Bilain.

- DUBREUIL, Jean (1642) - La Perspective Practique…par un Parisien, Religieux de la Compagnie de Iesus, Paris, Melchior and François Langlois.

- ALÉAUME and MIGON (1643) - La Perspective Spéculative et Pratique du Sieur Aléaume, ed. by Etienne Migon, Paris.

- BOSSE, Abraham (1648) - Manière Universelle de Mr Desargues pour Pratiquer la Perspective par Petit-Pied, comme le Géometral, Paris, the author.

- LECLERC, Sébastien (1669) - Practique de la Géométrie sur le Papier et sur le Terrain, Paris, Thomas Jolly.

- TROILI, Giulio (1672) - Paradossi per Pratticare la Prospettiva, senza Saperla, Fiori, per Facilitare l'Intelligenza, Frutti, per non Operare alla Cieca, Bologna, heirs of Peri.

- POZZO, Andrea (1693–1700) - Perspectiva Pictorum et Architectorum Andreae Pozzo Putei e Societate Jesu, Rome, Joannis Komarek Bohemi.

- LAMY, Bernard (26 February, 1701) - Traité de Perspective, ou sont Contenus les Fondamens de la Peinture, Paris, Anisson.

- BIBIENA, Ferdinando Galli (1711) - L'architettura Civile Preparate su la Geometria, e Ridotta alle Prospettive, Parma, P. Monti.

- TAYLOR, Brook (1715) - Linear Perspective: or, a New Method of Representing justly All Manner of Objects as They Appear to the Eye in all Situations, London, R. Knaplock.

- Cone of Vision (COV): The area of vision that emanates from our eyes is about 60 degrees wide, before distortion begins to affect what we see. Outside of the 60-degree angle, objects begin to blur. In linear perspective, the Cone of Vision is indicated with a 60-degree angle beginning at the station point; it is 30 degrees to the left and right of the line of sight.

- Distance Points & Distance Lines: The two vanishing points on the horizon, at which diagonal 45-degree lines in the horizontal plane meet, are known as distance points. They are the same distance from the central vanishing point as the viewer is from the picture plane. If, within a picture, a horizontal square parallel to the picture plane can be identified, extending the diagonals to the horizon will give the distance points. The distance of the viewer to the picture plane is then known, and it becomes possible, by working backwards, to create a plan of the space within the picture.

- It is debatable whether the correct viewing distance was of any importance to the early users of perspective. In reality, however, there are paintings that show an approach that could not be considered to be purely Albertian. Many paintings show a floor grid with a recession that appears to be governed solely by the 45-degree diagonals of the grid squares being drawn towards a point at eye level, often placed at the edge of the painting. This approach is often referred to as the "distance point" method, and these points are known as "distance points" simply because the distance between them and the central vanishing point is the same as the distance between the viewer and the picture plane. It follows that if the vanishing point for the orthogonals is placed centrally, and the edge of the painting is used as a distance point, then the "correct" viewing distance is half the width of the painting. It also follows that the angle of view is 90 degrees. It has been generally assumed that these points have been placed at the edge of the paintings for completely practical reasons.

- We do not know the precise moment at which the two lateral points received their theoretical explanation as the "point of distance." We do not know if Brunelleschi understood that their distance from the central vanishing point represented, according to the scale of the picture, the distance between the vantage point of an ideal spectator and the plane of the image.

- Field of Vision (FOV): The area wider than the Cone of Vision, extending out from the viewer at 90˚, is where distortion begins.

- Converging Lines: In perspective drawing, parallel lines converge towards a single vanishing point.

- Diminishing Forms or Diminution: Refers to the apparent size of objects and how they become smaller as the distance between the object and the viewer/artist increases; this is a key tenet of linear perspective.

- Foreshortening: Refers to the fact that although things may be the same size in reality, they appear to be smaller when farther away, and larger when close up. Foreshortening is often used in relation to a single object, or part of an object, rather than to a scene or group of objects.

- An excellent example of this type of foreshortening in painting is The Lamentation over the Dead Christ (c.1470–1480, Pinacoteca di Brera, in Milan), a work by Andrea Mantegna.

- Ground Line (G): A line drawn to establish the surface on which an object or objects rest; it is used to determine accurate vertical measurements in perspective drawings. The base or lower boundary of a picture plane. The term may also be applied to a similar construction line used anywhere in the picture to measure off points or to determine the scale of a figure.

- The ground line is always parallel to the horizon line. In perspective drawings that show top and side views, the side view of an object is placed on the ground line. It is usually the plane that is supporting the object depicted or the one on which the viewer stands.

- Horizon, Apparent Horizon, Visible Horizon, Skyline: The line at which the sky and Earth appear to meet. For observers near sea level, the difference between the geometrical horizon (which assumes a perfectly flat, infinite ground plane) and the true horizon (which assumes a spherical Earth surface) is imperceptible to the naked eye. For someone on a 1000-meter hill looking out to sea, the true horizon will be about a degree below a horizontal line.

- Horizon Line (HL): The actual horizon, where Earth and sky appear to meet, excluding obstructions like hills or mountains. In perspective drawing, the horizon is at the viewer's eye level. Artists tend to use the term "eye level," rather than "horizon," because in many pictures, the horizon is hidden by walls, buildings, trees, hills, etc. In perspective drawing, the curvature of the Earth is disregarded and the horizon is considered the theoretical line to which points on any horizontal plane converge (when projected onto the picture plane) as their distance from the observer increases.

- Lines above the horizon line always converge down to it; lines below always converge upward to it.

- Line of Sight: An imaginary line traveling from the eye of the viewer to infinity. In all paintings with perspective substructures, the line of sight is parallel to the ground. Lines which travel parallel to the line of sight are called orthogonals, which in a perspective drawing converge at the vanishing point.

- One-point Perspective: A drawing has one-point perspective when it contains only one vanishing point on the horizon line. This type of perspective is typically used for images of roads, railway tracks, hallways, or buildings viewed so that the front is directly facing the viewer. Any objects that are made up of lines either directly parallel with the viewer's line of sight or directly perpendicular (the railroad slats) can be represented with one-point perspective. These parallel lines converge at the vanishing point.

- One-point perspective exists when the picture plane is parallel to two axes of a rectilinear (or Cartesian) scene—a scene which is composed entirely of linear elements that intersect only at right angles. If one axis is parallel to the picture plane, then all elements are either parallel to the picture plane (either horizontally or vertically) or perpendicular to it. All elements that are perpendicular to the picture plane converge at the vanishing point.

- Orthogonal: Orthogonal is a term derived from mathematics. It means "at right angles" and is related to orthogonal projection, a method of drawing three-dimensional objects. Orthogonal lines are imaginary lines which are parallel to the ground plane and the line of sight of the viewer. They are usually formed by the straight edges of objects. Orthogonal move back from the picture plane. Orthogonal lines always appear to intersect at a vanishing point on the horizon line, or eye level. Although we do not generally note the convergence of orthogonal lines in real life, sometimes they become apparent when standing in the middle of a road, train tracks or on a long straight urban street.

- Perpendicular: At a right, or 90-degree angle to a given line or plane. An absolutely vertical line and an absolutely horizontal line are perpendicular to each other.

- Picture Plane (PP): In painting, photography, graphical perspective, and descriptive geometry, a picture plane is an imaginary plane located between the "eye point" (or oculus) and the object being viewed. It is typically coextensive with the material surface of the work and is ordinarily a vertical plane perpendicular to the sightline to the object of interest.

- Plane: In mathematics, a plane is a flat, two-dimensional surface that extends infinitely far. In colloquial language, it refers to any flat surface, such as a wall, floor, ceiling, or level field.

- Prospettiva: From the Latin "perspicere," meaning "to see distinctly."

- Projection: From the Latin "proicere," meaning "to throw ahead." A projection is a straight line drawn through different points of an object from a given point to an intersection with the plane of projection.

- Receding: Moving away from the viewer, the opposite of which is "Advancing."

- Station Point (SP or S): The position of the artist's eye relative to the object he or she is drawing. Sometimes referred to as "eye point," "point of view," or "viewpoint."

- Transversal: Transversal lines are lines that are parallel to the picture plane and to one another. They are always at right angles to orthogonal lines.

- Two-point Perspective: A drawing has two-point perspective when it contains two vanishing points on the horizon line. One point represents one set of parallel lines, the other point represents the other. Two-point perspective exists when the picture plane is parallel to a Cartesian scene in one axis but not to the other two axes.

- Vanishing Point (VP): Imaginary points on the horizon line in one- and two-point perspective where orthogonal lines receding into space appear to converge.

- Brook Taylor's "Linear Perspective: Or, a New Method of Representing Justly All Manner of Objects as They Appear to the Eye in All Situations" (1715) is said to have been the first to use the phrase "vanishing point."

- The Jesuit friar Andrea Pozzo, the author of "Perspectiva Pictorum et Architectorum" (1693–1700) and the monumental ceiling of Sant'Ignazio in Rome, was the first commentator to systematize the use of the "vanishing distance point" (punctum distantiae) to resolve a broad spectrum of perspective problems. He even anticipated the geometrical drawing technique from descriptive geometry by introducing the simultaneous use of plan and elevation to originate a detailed solution to the architectural ornamentation of the classical orders.

from: Bruce MacEvoy, "Two Point Perspective" 2015.

-

DEREGOWSKI JB, Parker DM. "On a changing perspective illusion within Vermeer's 'The Music Lesson'." Perception. 1988;17(1):13-21.

- GARCÍA-SALGADO, Tomás. "Some Perspective Considerations On Vermeer's 'The Music Lesson'," 2009.

- GARCÍA-SALGADO, Tomás. "The Music Lesson and its Reflected Perspective Image on the Mirror." Art+Math Proceedings, University of Boulder Colorado, 2005, 156–160.

- GARCÍA-SALGADO, Tomás. "Modular Perspective and Vermeer's Room." Bridges London (Conference Proceedings 2006, Editors: R. Sarhangi & J. Sharp)

- GUTRUF, Gerhard, and STACHEL, Hellmuth. "The Hidden Geometry in Vermeer's 'The Art of Painting,'" Journal for Geometry and Graphics vol. 14, no. 2 (2010): 187–202.

- GUTRUF, Gerhard, and Hellmuth STACHEL. "Reconstructing Vermeer’s Perspective in 'The Art of Painting'." Vienna; Vienna University of Technology. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- HALLORAN, Thomas O. "Reconstructing the Space, in Vermeer's 'Officer and Laughing Girl,'" Anistorian: In Situ, vol. 8, September 2004.

- HEUER, Christopher. "Perspective as Process in Vermeer," Anthropology and Aesthetics no. 38 (Autumn, 2000) 82–99.

- LORDICK, Daniel. "Parametric Reconstruction of the Space in Vermeer's Painting 'Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window'," Journal for Geometry and Graphics, Volume 16 (2012), No. 1, 69–79.

- JOHNSON, C. Richard, Jr. and SETHARES, William A., with contributions by: FRANKEN, Michiel, JOHNSON, C. Richard, Jr, NOBLE, Petria, SETHARES, William

- KOBAYASHI-SATO, Yoriko. "Vermeer and his Thematic Use of Perspective," Amsterdam. In his Milieu: Essays on Netherlandish Art, in Memory of John Michael Montias, 2009, 212.

- LEE, Yiwei Christina and CHEW, Mei Ru Madeleine. "The Length of Vermeer's Studio"

- LIVIANDI, Aditya. "Reconstruction of Vermeer's 'Music Lesson': An application of Projective Geometry"

- STEADMAN, Philip. Vermeer's Camera: Uncovering the Truth behind the Masterpieces. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- STEADMAN, Philip. Vermeer's Camera. 2001.

- A., STOLWIJK, Chris, VERSLYPE, Ige, WEIDEMA, Sytske and WHEELOCK, Arthur K., Jr. "Optical Devices, Pinholes and Perspective Lines," Counting Vermeer: Using Weave Maps to Study Vermeer's Canvases. RKD Monographs, 2018.

- WADUM, Jørgen. "Vermeer in Perspective," in exh. cat. Johannes Vermeer. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Royal Cabinet of Pictures Mauritshuis, The Hague (1995–1996), 67–79.

- WADUM, Jørgen. 1995. "Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) and His Use of Perspective." In Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice, edited by Arie Wallert and Erma Hermens, 148-154.

- WADUM, Jørgen. "Vermeer and Spatial Illusion," in The Scholarly World of Vermeer. Waanders Publishers, Zwolle, 1996, 31–50.

- WALD, Robert. "The Art of Painting': Observations on Approach and Technique," in Vermeer: Die Malkunst, edited by Sabine Haag, Elke Oberthaler and Sabine Pénnot, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna: Residenz, 2010, 314.

In brief, this is how it can be done. Once the central vanishing point has been determined, the drawing or canvas is attached to a wall or laid face up on a large table. The horizon line, determined by the height of the central vanishing point, is developed by extending a horizontal line through the vanishing point to the left and right, lengthy enough so that the two distance points can be properly accommodated, equally spaced from the central vanishing point. Then, a pin is inserted into the locations of the distance points. Finally, a string is attached to the pin and pulled taught thereby allowing the artist verify or construct the “distance” lines with precision and without, if necessary, disturbing the surface of the canvas. Obviously, the pin-and-string technique is more elaborate and time consuming when used in conjunction with distance points, especially once the actual painting phase has commenced. In part, this may explain why Vermeer's distant-point constructions are somewhat less accurately contrived that the orthogonals. However, it must also be considered that the effects of misinterpretation in two-point perspective construction are greatly exacerbated given that the distance between the original segment and its appropriate distance point is very long: even the slightest measurement may give disastrous results.

Another factor crucial in gauging the accuracy of Vermeer's perspectives involves neither theoretical understanding nor interpretative ambiguities, but the painting process. It is not only possible but virtually inevitable that even when the perspective lines of the underdrawing are geometrically perfect, they will become lost when painted upon, and at times repainted, in order to give color and tone to the objects to which they belong. We find faulty vanishing lines not only in the earlier works done in a painterly style, but in the later works in which the painter went to great lengths to render the straight edges of objects as straight as possible. It is also difficult to rule out that occasionally the actual objects that Vermeer painted from were not geometrically regular (see the braces of the Spanish chairs).

In Vermeer's perspective there are a number objects which are set neither perpendicularly nor at 45 degrees to the observer's line of sight, but rotated at intermediate angles, such as chairs, window frames and stools. In the relatively few cases in which the perspectives of such oriented objects are contemplated in perspective literature of the past, the vanishing points associated with their construction were referred to specifically as "accidental" points (poinct accidental), rather than “tier” points, as distance points were often referred to. Today, there exists no equivalent for this term. It is likely that a need for a specific term came about—"accidental" may suggest an element of unusualness—because those preoccupied with high degrees of perspective accuracy found that objects set perpendicularly or at 45 degree angles to the viewer's line of sight were far easier to develop than those set intermediate angles, in both conceptually and in practice. In Vermeer's paintings there are more than a dozen of such objects, which include chairs, stools, windows frames and an easel (The Art of Painting). It must be said that degree of accuracy of the perspective construction in these cases is generally significantly inferior with respect to those of objects developed with one- or distance-point constructions. In some cases the vanishing lines appear so inconsistent with perspective geometry that one has the impression that they were, as artists are want to say, eye-balled (e.g., the foreground chair of Officer and Laughing Girl).

Given the variability of the perspectival inaccuracies encountered in Vermeer's paintings, it may be arbitrary to relate them to any particular process he might have used to develop perceptive.

Errors Vermeer's Perspectives

Since there is no objective method for determining the exact angle of a hand-painted segment, it is difficult to identify the nature of errors that are encountered. Notwithstanding, it could be said that there are essentially three types of errors in perspective: systematic errors, accidental errors, and ad hoc errors.

A systematic error is an error that results from a misunderstanding of one or another rule of perceptive. For example, in Woman with a Pearl Necklace, the different bundles of orthogonals of the mirror, window muntins and table intersect at very different points rather than meeting at a single vanishing point.

An accidental error is usually a casual mismeasurement in the initial projection, a slip of the artist's hand or repeated repainting during the painting phase. Such errors may have been so small as to be considered as negligent by the painter, or simply too small to be noticed by him. For example, the orthogonal lines caused by uppermost leadings of the window in A Lady Standing at a Virginal do not converge at the central vanishing point. Moreover, it is impossible to know if the leadings were incorrectly drawn by Vermeer or if, in the case they represent real objects in Vermeer's studio, physical irregularities in the objects themselves. This may explain also why the vanishing lines associated with the braces of the Spanish are generally less conforming to geometric accuracy than the orthogonals.

An ad hoc error is an intentional error meant to purposely alter some element of a correct perspective scheme in order to modify an aesthetic outcome. Ad hoc errors are the most difficult to identify in that it is largely a matter of interpretation as to what is intentional and what is not. If the perspective of the jug of The Milkmaid were correct, the viewer would have been able to see the flat disk of milk inside it. SInce this passage is so crucial to the painting, it is doubtful that Vermeer would not have noticed it.

Perspective Diagrams

There are two groups of diagrams below. The first group (left-hand column) is the fruit of a common-sense approach. It is based on the reasonable assumption that Vermeer was familiar with linear perspective and therefore knew that all orthogonal lines must converge at a single, vanishing point, referred to in the present study as the central vanishing point. This assumption is supported by physical evidence found in 13 paintings, which present a detectable hole in the canvas in which, presumably, a pin was inserted. This trick was used by a number of other Dutch painters. For this reason and for the sake of illustrating the geometric principles behind Vermeer's perspectives, only those lines which deviate clearly from what would be expected are not connected to their appropriate vanishing points.

In three paintings, Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, A Maid Asleep and The Little Street, it was not possible to derive a vanishing point, and hence, a horizon line due to the combined difficulties of interpreting the physical evidence presented by the pictures themselves as well as the uncertainties of the perspective construction of these three works.

The second group of diagrams is based on the most careful consideration of visual evidence embedded in the painted surface, and nothing else. Therefore, there are no vanishing points or horizon lines; only raw perspective lines which have been retrieved but not mediated in any way.

- Christ in the House of Martha and Mary

- A Maid Asleep

- Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window

- Officer and Laughing Girl

- The Milkmaid

- Girl Interrupted in her Music

- The Girl with a Wine Glass

- The Little Street

- The Glass of Wine

- The Music Lesson

- Woman with a Lute

- Woman with a Water Pitcher

- Woman with a Pearl Necklace

- Woman Holding a Balance

- The Concert

- A Lady Writing

- The Art of Painting

- The Astronomer

- The Geographer

- The Love Letter

- The Guitar Player

- Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid

- A Lady Standing at a Virginal

- A Lady Seated at a Virginal

- Christ in the House of Martha and Mary

- A Maid Asleep

- Girl Reading a letter at an Open Window

- Officer and Laughing Girl

- The Milkmaid

- Girl Interrupted in her Music

- The Girl with a Wine Glass

- The Little Street

- The Glass of Wine

- The Music Lesson

- Woman with a Lute

- Woman with a Water Pitcher

- Woman with a Pearl Necklace

- Woman Holding a Balance

- The Concert

- A Lady Writing

- The Art of Painting

- The Astronomer

- The Geographer

- The Love Letter

- The Guitar Player

- Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid

- A Lady Standing at a Virginal

- A Lady Seated at a Virginal

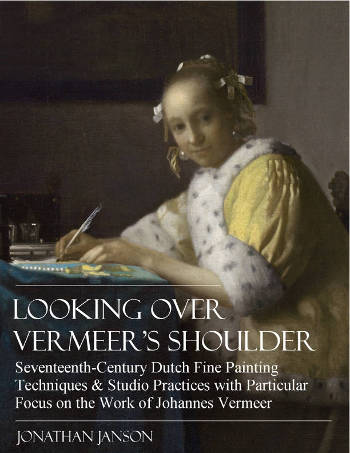

LOOKING OVER VERMEER'S SHOULDER

The complete book about Johannes Vermeer's and 17th-century fine-painting techniques and materials

by Jonathan Janson | 2020

Enhanced by the author's dual expertise as both a seasoned painter and a renowned authority on Vermeer, Looking Over Vermeer's Shoulder offers an in-depth exploration of the artistic techniques and practices that elevated Vermeer to legendary status in the art world. The book meticulously delves into every aspect of 17th-century painting, from the initial canvas preparation to the details of underdrawing, underpainting, finishing touches, and glazing, as well as nuances in palette, brushwork, pigments, and compositional strategy. All of these facets are articulated in an accessible and lucid manner.

Furthermore, the book examines Vermeer's unique approach to various artistic elements and studio practices. These include his innovative use of the camera obscura, the intricacies of his studio setup, and his representation of his favorite motifs subjects, such as wall maps, floor tiles, and "pictures within pictures."

By observing closely the studio practices of Vermeer and his preeminent contemporaries, the reader will acquire a concrete understanding of 17th-century painting methods and materials and gain a fresh view of Vermeer's 35 masterworks, which reveal a seamless unity of craft and poetry.

While the book is not structured as a step-by-step instructional guide, it serves as an invaluable resource for realist painters seeking to enhance their own craft. The technical insights offered are highly adaptable, offering a wealth of knowledge that can be applied to a broad range of figurative painting styles.

LOOKING OVER VERMEER'S SHOULDER

author: Jonathan Janson

date: 2020 (second edition)

pages: 294

illustrations: 200-plus illustrations and diagrams

formats: PDF

$29.95

CONTENTS

- Vermeer's Training, Technical Background & Ambitions

- An Overview of Vermeer’s Technical & Stylistic Evolution

- Fame, Originality & Subject Matte

- Reality or Illusion: Did Vermeer’s Interiors ever Exist?

- Color

- Composition

- Mimesi & Illusionism

- Perspective

- Camera Obscura Vision

- Light & Modeling

- Studio

- Four Essential Motifs in Vermeer’s Oeuvre

- Drapery

- Painting Flesh

- Canvas

- Grounding

- “Inventing,” or Underdrawing

- “Dead-Coloring,” or Underpainting

- “Working-up,” or Finishing

- Glazing

- Mediums, Binders & Varnishes

- Paint Application & Consistency

- Pigments, Paints & Palettes

- Brushes & Brushwork

or anything else that isn't working as it should be, I'd love to hear it! Please write me at:

or anything else that isn't working as it should be, I'd love to hear it! Please write me at: