Woman Holding a Balance

c. 1662–1665Oil on canvas

42.5 x 38 cm. (16 3/4 x 15 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C

A young woman delicately holds an empty pair of scales in her right hand. She seems to be waiting for them to balance out before she weighs something, probably the gold coins at the edge of the table.

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas

42.5 x 38 cm. (16 3/4 x 15 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Also on the table are some jewels, pearl necklaces and a gold chain. On the far wall hangs a painting of the Last Judgment (fig. 1) while: on the left wall facing the woman is a mirror. The contrast between the valuable objects on the table, the Last Judgment and the scales, symbols of the Judgment itself, are intended to remind the viewer of the importance of resisting the temptation of earthly riches and living moderately in order to obtain salvation. The calmness of the young woman's feature's indicates that she is capable of living according to these principles. The subject of moderation appears in other paintings by Vermeer, such as The Girl with the Wine Glass, in which the stained-glass window features a female figure who can be identified as an allegory of Temperance. In the present work, the contrast between the various objects is what fills the painting with meaning.

While the presence of the Last Judgment indicates that the message of this painting has religious connotations, we should not forget its similarities to other works by Vermeer of the mid-1660s; such as Young Woman with a Water Jug, and Woman in Blue Reading a Letter. These two works, as with the present one, depict a young woman in a thoughtful attitude within a domestic interior accompanied by symbolic elements. In conclusion, we are dealing with images in which the artist imbues an everyday context with an atmosphere of idealization and calm that can be related to universal issues such as purity, love and, in this case, moderation.

Vermeer's paintings of around 1665 reach an unprecedented level of harmony and serenity. The delicate transition between areas of light and shade and the rhythm established by the colour relations contribute to the refinement of the scene: the woman's blue jacket echoes the piece of material on the table, while the colour of the curtain on the left reverberates in the ochre tones on the table, the orange and yellow of the woman's stomach and in the verticals of the picture frame on the far wall. The young woman's concentrated expression and the strict geometry of the composition, which alternates in a masterful way the horizontal and vertical lines with the diagonal created by the light entering from the window, are other elements which contribute to the exquisite sophistication of this painting. It is likely that when he painted this work Vermeer was inspired by a painting of De Hooch's, Woman Weighing Coins (fig. 2). The similarities of the subject and composition between the two works are not coincidental and indicate the relation between De Hooch and Vermeer, the first often the most innovative, while the second transformed his models by giving them a more spiritual, abstracted appearance. In Pieter de Hooch's work the spectator focuses on the anecdotal details, such as the gesture of the woman's hands and the textures of the materials and the geometrical construction of the scene. Vermeer uses these same elements, together with others such as the distribution of the areas of light and shade, converting them into verticals which serve to transcend the everyday and create a scene which conveys the feeling of a timeless truth.

Pieter de Hooch

c. 1664

Oil on canvas, 61 x 53 cm.

Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

Around half of Vermeer's works produced between 1657 and 1670 were acquired by one collector, Pieter van Ruijven, probably including the present canvas.

Woman Holding a Balance gives the impression, even more powerfully than Woman Putting On Pearls, of being a distillation, and an open assertion, of the values implicit in Vermeer's work as a whole. Indeed, the similarities between the two paintings—the juxtaposition of the mirror and the curtained window, the cloth piled in the left foreground on the heavy wooden table, even the pearl necklace itself, which lies on the table of Woman Holding a Balance, a virtual allusion to Woman Putting on Pearls—suggest that Vermeer is more conscious than usual in these two paintings of expressing different facets of a single vision.

The values embodied in Woman Holding a Balance are asserted over against conventional moral and religious judgment even more explicitly than they are in Woman Putting on Pearls. A large Baroque painting of the Last Judgment hangs conspicuously on the rear wall of the room, situating the woman within an apocalyptic frame of reference and counterpointing her gesture. The light that illuminates her breaks into the painting from above, surrounding her with what at first glance may seem ominous, encroaching shadows; its point of entrance, moreover, resembles the "lurid yellow nimbus" of the Christ of the Last Judgment (fig. 3).

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas

42.5 x 38 cm. (16 3/4 x 15 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

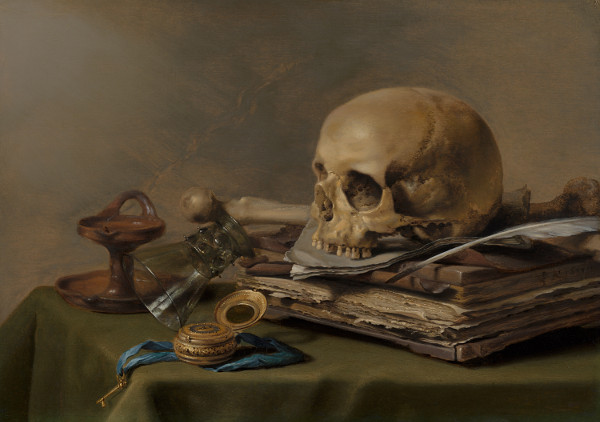

Commentators who have responded to this thematic counterpoint have almost invariably assumed that the painting in the background provides "the key that unlocks the allegory" of the painting. Thus we are told that the gold coins on the table and the pearls spilling from the jewelbox represent "the dangers of worldliness,"everything that mortal man tries vainly, in the face of his mortality, to hold on to" and that the woman's presence is an embodiment of Vanitas (fig. 4), or a reminder of "the transistorizes of human life," or "another statement about the importance of temperance and moderation in the conduct of one's life.

Pieter Claesz

1630

Oil on panel, 39.5 x 56 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

But this, again, is to opt for a meaning that is at direct odds with the immediate spiritual impact of the painting. Woman Holding a Balance provides us not with a warning but with comfort and reassurance; it makes us feel not the vanity of life but its preciousness. Against the violent Baroque agitation of the painting behind her, the woman asserts a quiet, imperturbable calm, the quintessence of Vermeer's vision. Against its lurid drama of apocalyptic judgment, and the dialectic of omnipotence and despair it generates, she poses a feminine judiciousness, a sense of well-being predicated on balance, equanimity, and a pleasure in the finest distinctions. Against a demonic, emaciated fiction of transcendence, she exists as a moving embodiment of life itself, and what is given to us in it. And in all these oppositions, one cannot but feel the effortlessness of her triumph.

Dresden Letter Reader throughout his career. Out of her shape he evolves, sometimes as directly as in the Reader at Amsterdam, the rapt, remote inhabitants of his world. But the devices that separate us from the girl at Dresden give place in later works to the isolating artifice of style itself. The subjects of the pictures become richer; they gather not the movement of life so much as of distantly related, barely perceptible symbolic meanings. In this picture a connection between the lady, who seems to be weighing pearls against gold, and the painting that hangs on the wall behind her, turns the incident into a fanciful allegory of the Last Judgment. Elsewhere these references are more open; it is clear that we are intended to gather them from the Gold Weigher. Such subtle parallels have, as has been noticed, a deep significance for the painter. Yet there is no weakening of the visible subject. His purpose is entirely concerned with the forms that we see. Here it seems that the object of the allegorical play is to enrich with a depth beyond measure the nature of this lady and her commonplace act: she takes on something of the character of Saint Michael, the weigher of souls in the part of the Last Judgment which is hidden. Others of Vermeer's allegories are less readily construed: they are of a kind beyond design whose keys are buried in the recesses of his nature.

Whether or not his meaning was within the grasp of the time, Vermeer's contemporaries clearly felt the magnetism of his later work. In the middle sixties De Hooch and Pieter Janssens Ellinga (fig. 5) both painted imitations of the Gold Weigher and the pictures related to it. It is curious how much of the development of De Hooch's work may be traced in the paintings with which he decorates his subjects. His removal to Amsterdam is signalized by the appearance on the wall behind one of his drinking scenes of the Rape of Ganymede by the great master of the town. But he turned in another direction; in the late sixties when he set a music party in a chamber of Amsterdam Town Hall he inserted the School of Athens in the place for which Rembrandt had designed his Conspiracy of the Batavians. It was a symbolic concession to taste, a denial o his own tradition, and it heralded the elegant arrangements which occupied him in the last.

Pieter Janssens Elinga

-

Oil on canvas, 66 x 63 cm.

Museum Bredius, The Hague

Perspective boxes and perspectives

Because of Vermeer's obvious concern with precise perspective (most notably, perhaps, in The Music Lesson) and because his contemporaries associated him with Fabritius, scholars have speculated whether certain entries in the Dissius inventory of 1682 and the Amsterdam catalogue of 1696 refer to perspective boxes. In the 1682 inventory there were listed, among the twenty Vermeers, "three ditto by the same in boxes," while in 1696, item 1 was" A young lady weighing gold, in a box by J. van der Meer of Delft...". The consensus is that this is unlikely to have been the case. Images designed for perspective boxes (fig. 7 & 8) look distorted unless viewed in such a box. A considerable part of their charm lies in the magical way their distortions disappear when seen through the peephole. None of Vermeer's surviving works betrays these characteristics. Their perspectives are not anomalous. The only work specified in a box, in the 1696 catalogue, is further identified as "extraordinarily artful and vigorously painted," and highly priced at 155 guilders. If, as seems likely, this was the painting now in Washington known as a Woman holding a balance, the most credible explanation of the box is that it was to protect so fine and valuable a work (fig. 6).

Frans van Mieris

1667

Oil on panel, 27 x 22 cm.

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden

Nevertheless, Vermeer shared Fabritius's and Hoogstraten's concern with perspective. As one of the mathematical arts, geometrical perspective had long been recognized as prime among the skills that in Quattrocento Florence had transformed painting from a manual craft into a liberal art. The painters of the Netherlands were well aware that Italian artists derided them as ignorant of the true principles of art. But there was more to the superiority of Italian art than perspective. Italians knew the true art of disegno, a term that embraced drawing and composition. They also knew the importance to great art of the subject: the istoria, or history, which should be taken either from the Bible or from classical history or mythology. Fabritius, Hoogstraten and Vermeer all appear to have been skilled, or "artful" (as it was then termed), intelligent and ambitious artists. Hoogstraten, in his writings, showed that he accepted the Italian criteria for great art. Vermeer appears to have believed he understood the principles of Italian art. In 1672, he was regarded by himself and others as fit to pronounce on the authenticity of several paintings attributed to Michelangelo, Titian, Raphael, Giorgione, Paris Bordone and others. Vermeer's fellow connoisseur, an older artist, Johannes Jordaen, had spent many years in Italy, and together they declared all the contested works to be rubbish and bad paintings.

None of these painters wholeheartedly emulated the Italian manner. But it would be a mistake to believe that Netherlandish painters of Vermeer's generation were unconcerned with anything more than the appearances of daily life, or that they saw geometry as the intellectual skill by which alone painting was elevated from a craft to a liberal art.

Samuel van Hoogstraten

c. 1655–1660

Oil and egg on wood, 58 x 88 x 60.5 cm.

National Gallery, London

Attributed to Samuel van Hoogstraten

1663

Oil paint, glass mirror and walnut, 42 x 30.3 x 28.2 cm.

Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit

Jennifer Henel

"Striking the Right Chord: Seeing Music in Dutch Genre Painting" - National Gallery of Art websiteFor many in the seventeenth century, the question of balance [in painting] was not only visual, it was also aural. Indeed, during that time there was an awareness of and interest in a concept later named synesthesia, from the Greek syn (union) and aísthesis (sensation), meaning the union of the senses. Since the 4th century BC, theorists and philosophers, including Aristotle, have explored the link between color and sound, investigating the relationship between chromatic and musical tones.

These concepts were recognized and refined over the centuries by numerous scholars, including the seventeenth-century German Jesuit priest Athanasius Kircher, who, among other topics, wrote extensively on music theory. One of Kircher's most important theories was his work on the correspondence of musical notes to specific colors, which he coded into a chart and published in 1646 (for an adaptation of this chart, see at right). According to Kircher, deep, dark sounds of minor notes are associated with cool, deep colors, while the warmer, brighter sounds of major notes are warmer, lighter colors. As a Jesuit priest, Kircher believed that the coexistence of sensory functions had profound implications in worship and that the immersion of sight and sound had the capacity, as one scholar wrote, to "move the passions, to produce strong emotional effects that, under properly controlled conditions, [could] ravish the soul and lead the faithful closer to the divine."

Kircher's articulation of the multisensory relationship between color and music resonates with Van Mander's advice for artists and suggests that the experience of looking at painting may engage viewers on a variety of sensory levels. For synesthetes, the integration of certain colors and shapes on an artist's panel or canvas may stimulate a musical experience, which would allow them to "hear" the painting."

Paintings need not depict music to convey musicality, as evident in even the quietest scenes, such as Vermeer's Woman Holding a Balance. While the subject matter and palette of this sublime painting imbue a sense of silence, a synesthete might hear major chords in the warm tones of the uppermost left, minor chords repeated in the rhythmic folds of dark blue cloth, an end refrain in the diagonal of the lady's arm, and a major resolve in the narrow, vertical strip of the warm, creamy wall.