The Music Lesson

c. 1662–1665Oil on canvas

73.3 x 64.5 cm. (28 7/8 x 25 3/8 in.)

The Royal Collection, The Windsor Castle

On the far side of a sunlit room with double windows a young woman stands to play on a clavecin. A man in elegant dress watches her and listens intently. Both figures are quiet and statuesque, as though the music were measured and restrained. Indeed, this painting is one of the most refined works in Vermeer's oeuvre. In it, figures, musical instruments, picture, mirror, table, tile patterns, and chairs, however realistically presented, are conceived as patterns of color and shape.

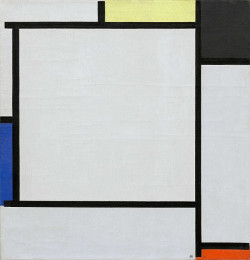

Piet Mondrian

1922

Oil on canvas, 55.6 x 53.3 cm.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Such abstract design principles are generally associated with the twentieth century. One cannot approach this work, however, without realizing that Vermeer calculated his compositional elements every bit as carefully as did Mondrian (fig. 1). The pattern of the roof beams, the repetition of black shapes on the back wall, the position of the table, chairs, and pitcher have all been painstakingly planned. Minor adjustments in the shapes of objects clearly testify to the artist's care about the precision of his composition. The pitcher on the table, for example, once had a thinner neck. Vermeer also adjusted the shape of the clavecin's lid to improve the composition. The lid is slightly wider to the right of the girl than it is to her left, a shift of alignment that lessens the tendency to visually connect the two halves of the lid design through the girl. Similar adjustments occur in at least two other paintings from this period: A Woman Holding a Balance, where he shifted the height of the bottom edge of the picture frame, and The Concert, where he adjusted the contour of the lid of the clavecin as it passes behind the standing woman.

Technical examinations have revealed that Vermeer initially painted the man slightly closer to the girl and then repainted his form in its present position. The girl's head also was once turned more toward the man. Its position was more like that in the mirror than it is now. By moving the man away and by turning the girl's head back, Vermeer succeeded in loosening their bond and allowed them to work more coherently in the total composition.

In this work, Vermeer actually gave us a clue that the scene was posed. We can vaguely perceive the shape of his easel and perhaps the artist's box in the mirror (fig. 2). Vermeer's implied presence thus gives the painting a different character from those in which the figures seem to exist in their own personal world. It makes the scene somewhat colder and more calculated. At the same time, however, it makes us aware of the intellect that went into its creation. However calculated the composition of this painting, it could not succeed without Vermeer's sensitive handling of light and color. Light floods the wall near the windows, but gently looses its force as it falls away from them. Shadows of objects, such as the mirror, are modulated because the light comes from different sources. Colors are also subtly adjusted according to the nature of the light that falls upon them. The letters of the inscription on the lid of the clavecin are ocher on the left of the girl but blue on her right. Similarly, the leading in the rear window is painted in ochers, but that in the adjacent window, against which the sky is seen, is blue.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 73.3 x 64.5 cm.

The Royal Collection, The Windsor Castle

The vividness of the scene is also created by the textural effects evident in the painting. Just as Vermeer depicted the tile roofs of the buildings in the View of Delft with different textures of paint, so here he varied his textures when representing a chair, a tablecloth, a reflection in the mirror, or a white porcelain pitcher. The brass studs on the chair, for example, are so thickly painted that they actually protrude from the surface plane. Similarly, the blue fringe of the chair cover has a bumpy texture.

Vermeer painted the table cover with a variety of layers over a basic ocher layer he applied the blues, yellows, reds, and oranges that combine to form the pattern of the design. These colors have been carefully applied, some densely, some thinly, to suggest the nubby character of the material (fig. 3). His technique for painting the pitcher, however, is quite the contrary. In this instance the surface is smooth and few brushstrokes are visible. Finally, when he wanted to depict the veins of the marble on the floor, he used broad, flowing strokes that are remarkably free and abstract.

The one area of this painting that differs in character, that lacks a similar interest in rendering textures, is the man. His figure is painted somewhat more thinly than that of the girl and with less emphasis on the definition of individual folds and materials. One wonders if Vermeer's decision to change the man's position was made sometime after the original execution of the painting, perhaps around 1665, a date that is also appropriate for the man's clothing.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 73.3 x 64.5 cm.

The Royal Collection, The Windsor Castle

The contradictions which have intruded upon the consistency of earlier works are here assimilated. Henceforward they are, as they have hardly been before, an essential part of Vermeer's subject; to reconcile them becomes perhaps the profoundest purpose of his pictures. In these two paintings (The Music Lesson (fig. 4) and The Concert (fig. 5) ) the surprising stroke is brought about. The reconciliation is accomplished in the first piece by a device of pictorial design; the whole plan of the pictures is based on a distaste for physical closeness and direct contact. In The Music Lesson, instead of human matter, the chief object of the painter's scrutiny is the great perspective. But the mirror foreshadows the incorporation of the paradox into the painter's style itself. The picture is not at first sight one of the most compelling of Vermeer's works. There is indeed a kind of prosaic tiredness about the representation, as if it showed the furthest ebb of the painter's confidence in the common forms. Its significance is in its design and in the scheme which it completes; only at one point, in the reflection, is Vermeer's fantasy fully extended in style.

Johannes Vermeer

Fig. 5

The Concert

Fig. 5

The ConcertJohannes Vermeer

It is not easy to be sure when these pictures were painted. The scenes have the domestic air of Vermeer's most characteristic works. The dresses seen in them were evidently in general use in the household; they cannot be precisely dated. Traces remain of the encrusted pigment typical of the early works, notably in the carpet which appears in The Music Lesson. But there are equally positive affinities with the later phase. Concurrently with the painting of the fashionable conversation pieces it seems that Vermeer also pursued his object in this other more private, more oblique direction, the direction which was properly his own. And in the passage of the reflection in The Music Lesson we have a beginning of the deliberate and marvelous style which distinguishes the latter half of his work. Behind the head in the mirror an easel is visible. It is often said The Music Lesson indicates the way in which Vermeer worked. But if it does so it is hardly in the usual sense. To complete the story we should probably need to discover the nature of the box which stands immediately behind the easel in the reflection, where we might expect to see the painter himself. Possibly his intimates understood the reference.

However personal his purpose here, Vermeer draws further on the resources of the time. The general scheme of composition recalls Leiden and such parties round the virginal were a subject of the genre painters of Haarlem. Similar still-lives of musical instruments often furnished the foregrounds of both schools. But the chief source of The Music Lesson, as of Vermeer's Leiden contemporaries, was the painting of Ter Borch. To him the genre school owed the device of the enigmatic lady who turns her back upon the spectator (fig. 6). In Delft De Hooch often made use of such figures, though not of their dramatic possibilities, and in later years he followed more and more closely Ter Borch's characteristic form. Very possibly Vermeer's debt goes further. Among Ter Borch's early uses of such figures were toilet scenes in which the theme is a delicate interplay between a lady and the reflection of her features in a mirror.

Gerrit ter Borch

c. 1654

Oil on canvas, 71 x 73 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Concert and The Music Lesson present elements of the style and the design of Vermeer's maturity; they also introduce that studied obliquity of theme, with its delicate symbolic accompaniment, which provides the matter of his later works. In such earlier pictures as the Girl Asleep as well as in the drinking scene at Brunswick we can discern a certain wit in the choice of the paintings which hang on the walls. They provide a barely noticeable embroidery of the painter's themes. So it is at first sight with The Concert. Here, hanging on the right, is a picture which can be identified. It is a Procuress painted by the Utrecht artist Van Baburen a little less than forty years before. A version of the composition, as has often been remarked, is in the Rijksmuseum; the original, no doubt the picture that Vermeer owned, has recently emerged from an English collection. It might seem that its appearance in The Concert was almost fortuitous. If it has any profounder purpose than the romantic landscape which hangs beside it Vermeer does not urge it. A connoisseur to whom its subject was legible might have gathered from the lascivious play that centres on Baburen's musician a sardonic reflection upon the appearance of disinterest with which the living figures take their places in front; he could hardly have been sure whether to credit it to the artist or his own fancy. The second picture removes the doubt. The Music Lesson, in which so much of the artist's thought is unfolded, illustrates perfectly, and we may be sure deliberately, the antithetical theme. The scene is decorated with a different subject, alike only in its lascivious reference. The subject is captivity; although only part is seen and the full perverse extremity to which the captive is reduced is veiled, no seventeenth-century connoisseur would have failed to recognize in it a Roman Charity. Evidently the picture was one of the Dutch works inspired by the composition that Rubens originated in the thirties.

On the lid of the virginal Vermeer has inscribed, and surrounded with an unparalleled richness of minute embellishment: Musica Letitiae Comes Medicina Doloris. The inscription is not only the legend of the instrument, it is also the epigraph of these two pictures and their oblique yet memorable celebration of the pleasures and sorrows of love.

Ter Borch's subjects influenced the whole of the genre school. But in later pictures a lady who turns her back on us is often discovered at the virginal, her head framed in a mirror or a picture on the wall. Several painters must owe the form to Vermeer's example. A notable occurrence of it is in one of Emmanuel de Witte's rare and beautiful domestic interiors; he may have taken it from De Hooch who used it similarly. In the background of a picture which is possibly by the painter of Refusing the Glass, known as A Soldier at a Window, Vermeer's motifis exactly imitated. Many of Vermeer's immediate followers note the value of a tilted mirror and its decorative dislocation of perspective; Metsu employs the device in the Beit Letter Reader. More than one of them use it, as does Pieter Janssens Ellinga with delicate effect, to reflect the bold pattern of a tiled floor. The artists who are to be seen in the genre paintings of the sixties seated at mirrors drawing sometimes recall not only the form but the vitreous impressionism of the passage in The Music Lesson. His contemporaries were evidently aware of the beauty of Vermeer's glass. The Concert also had its imitators; possibly it suggested two pictures to Jan Steen.

If we assume, as I think we must, that Vermeer represented more or less, accurately the rooms and household objects in his environment, we cannot but be struck by the way he manipulated individual components of this reality to achieve his ends. He used background pictures for his mise-en-scène much as a modern stage director uses reproductions, photographs, posters, and furniture to situate a milieu, to evoke a mood, or to make an ironic comment on a scene. Take, for example, the background picture (fig. 8) on the right-hand side of The Music Lesson. This is the Caravaggist picture-perhaps based on an original by Honthorst, Dirck van Baburen (fig. 7) or Matthias Stomer that Maria Thins already owned in Gouda and that appeared in the inventory list made up at the time she and her husband legally separated.

(fig. 7 (right) Cimon and Pero (Roman Charity)

(fig. 7 (right) Cimon and Pero (Roman Charity)Dirck van Baburen

1618–1624

Oil on canvas

(fig. 8 (left) The Music Lesson (detail)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 73.3 x 64.5 cm.

The Royal Collection, The Windsor Castle

Vermeer has only shown about two-fifths of this "Roman Charity," chiefly the back side of the head and the chained arms of Cimon, whom we know to be, but cannot see, sucking his daughter's breast. What bearing does this background picture have on the scene represented? A standing young woman is viewed from the back, her face reflected in the forward-leaning mirror above her. On the lid of the virginal she is playing on are inscribed words about music, "the companion of joy, the balm of sorrow." A gentleman listens to her in silence. The presence of the painter—ubiquitous intruder, seer, voyeur—is barely suggested by the easel adumbrated in the mirror. A tenor viol lies on the marbled floor, unheeded. The mood is pensive, melancholy, oppressive. The picture on the wall hints, by focusing only on Cimon in chains, that the gentleman-listener is enthralled by the young woman. He is bound by virtual fetters, a metaphor for Cimon's irons. The analogy may be extended a step further: milk and music, each in its way, assuage the pains of captivity.

Matthias Stomer

c. 1630

Oil on canvas

The Steven and Dorothea Green Collection

Roger Harmon

"'Musica laetitiae comes' and Vermeer's 'Music Lesson'"Oud Holland – Journal for Art of the Low Countries

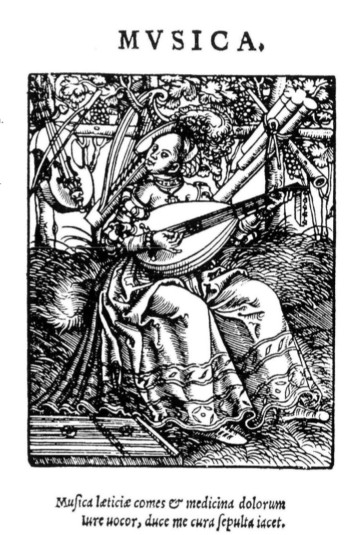

Near the vanishing point of Vermeer's so-called Music Lesson intersect the figure of a woman, standing with her back to the viewer and playing the muselar, and a motto painted on the inside of the instrument 's raised lid (fig. 8). Partially obscured by the woman, the motto (completed from sources to be discussed below) reads as follows:

MVSICA · LETITIÆ · CO[ME]S / MEDICINA · DOLOR[IS]

[music: pleasure's companion, remedy of sorrow]

The woman's playing works its magic on a man standing in semi-profile to the right and listening intently. His and the woman's relationship is unclear, though, an ambiguity captured by the motto. Are they emotionally attached? Music, 'comes laetitiae', is the food of love. Must they part? Music, 'medicina dolorum', eases pain.

The power to move the soul claimed by the motto on music's behalf lies in the nature both of music and of the soul as perceived in antiquity and in the Renaissance. A celebrated topic, it was conveyed by the laus musices (praise of music), a body of lore invoked in various genres by writers from Quintilianus and Boethius to Shakespeare. Musica homines laetificat (music cheers men) wrote Johannes Tinctoris, 'musica tristitiam depellit' (music dispels sadness), general antecedents of the motto.

The motto also decorates virginals in paintings by Pieter Codde (1599–1678), Gonzales Coques (1618–1684) and Karel Slabbaert (c. 1619–1654) as well as harpsichords made in 1624 and 1640 by Andreas Ruckers (fig. 9) of Antwerp. Four vanitates by Edwaert Collier (c. 1640-after 1706) feature it written on a piece of paper hanging from a table bearing book, globe, skull and musical instruments. Entries in the album amicorum (compiled 1599–1606) of Johannes Cellarius (1580–1619), syndic in Nuremberg, and in the lute manuscript (finished in 1640) of Johannes Stobaeus Kapleemeister at Konigsberg, testify to its resonance in Germany.

Johannes Ruckers (attributed to)

1640

Antwerp

Poplar, spruce, oak, bone, iron, brass, and paper, l 150.0 x 48.0 x 22.0 cm

l 106.0 cm × w 42.5 cm × h 78.0 cm

Koninklijk Oudheidkundig Genootschap, Amsterdam

One other source of the motto has been made known to date, a manuscript partbook containing vocal music in the hand of Nicolaus Baseler 'Francusanus' and dated 1569 (fig. 10). In 16th-century Germany, no collection of music or treatise on the subject was complete without a prefatory laus musices. The Wittenberg organist and professor Hermann Finck's treatise Practica Musica, published in Wittenberg in 1566 by the heirs of Georg Rhau was no exception. After the dedicatory epistle appears an emblem. There, Musica, surrounded by the instrumentarium of her art, speaks the words destined a century later to transport laus musices themes into Vermeer's Music Lesson:

Musica laeticiae comes & medicina dolorum

Iure vocor, duce me cura scpulta iacet.

[Musica, pleasure's companion and remedy of sorrow, I am rightly called; when I'm in charge, care lies buried.]

from: Hermann Finck, Practic Musica (Wittenberg: Georg Rhau's heirs, 1556), woodcut on paper, 12 x 7.5 cm.

Württembcrgisehe Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart