The Girl with a Wine Glass

c. 1659–1660Oil on canvas

78 x 67 cm. (30 3/4 x 26 3/8 in.)

Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Brunswick

There is general agreement that the canvas was painted slightly later than The Glass of Wine in Berlin and Young Woman Interrupted at Music in the Frick Collection. The Berlin and Braunschweig paintings are identical in size, but here the format is vertical and the main figures are placed much closer to the picture plane, as they are in the smaller Frick canvas. The three compositions have in common the progression on the right from a woman seated in approximate profile to a man standing close behind her, with a table to his side and a painting on the wall behind him (fig. 1). The pattern of floor tiles in the Young Woman with a Wine Glass is very similar to that in the Berlin picture, while the stained-glass window is the same but brought forward, opened wider, and illuminated differently.

c. 1659–1660

Oil on canvas, 78 x 67 cm.

Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Brunswick

For all these similarities, however, what is most remarkable about the Braunschweig picture is its somewhat incoherent composition, when judged by the exacting standards of the Berlin design. For example, the spatial relationship of the table to the figures in the foreground is unclear, and only slightly improved by the white cloth thrown into cover up the problem. The shape of the bowing gentleman is also awkward: the contours that in the Berlin and Frick pictures lead so effectively into or around the female figures here form a nearly symmetrical arch of folds, which fall where they are needed to fill ambiguous areas, and foil the thrust forward of the man's head and hand (an effect more expected of an artist like Samuel van Hoogstraten than of Vermeer). The brisk recession of the floor, which was already risky in the Berlin composition, has now cost the walls their definition as planes and as the perpendicular limits of the room. Out of necessity, the open window helps to define the corner and connect the table and the chair behind it with the walls. The seated male figure serves as a cornerstone for the structure, holding together rectangular elements and leftover zones of space (which have little of the presence one admires in most works by Vermeer). Later figures by the artist, although framed in a similar manner, appear unconstrained by comparison.

These would be harsh judgements if applied to another painter, but Vermeer shows greater refinement in earlier works. The same might be said for the behaviour of the figures in the Braunschweig picture, when compared with the couples in the Berlin and Frick paintings. We have moved from the world of Gerard ter Borch to that of Frans van Mieris, where lecherous smiles and embarrassed grins occur more frequently. The third figure (or 'fifth wheel') in the Braunschweig canvas also recalls characters depicted by Van Mieris but more strongly resembles the idle dandy in A Musical Party (fig. 2), of the early l650s, by Gerbrand van den Eeckhout. Of course, the setting as a whole and to some extent the arrangement of the figures was influenced by Pieter de Hooch. As a result, the Young Woman with a Wine Glass has a composite quality that is not sensed in Vermeer's most similar works. He had an exceptional ability to blend oil and water when combining sources, but here the mixture remains incomplete.

Gerbrand van den Eeckhout

Early l650s

Oil on canvas, 50.8 x 64.5 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

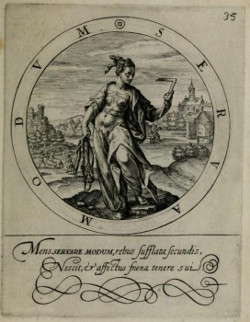

The figure in the background of this simple and ordered interior rests his head on his hand in a melancholy attitude, while in the foreground a young woman takes a wine glass which an elegantly dressed man hands to her. The young woman's smile and the man's attitude indicate that we are witnessing a scene of seduction, and that the girl is largely accepting her admirer's advances. The woman's gesture of looking out to the spectator in order to involve us in her world, indicates that it is the two men rather than she who are seduced and unable to resist her tempting presence. In the window that hangs on the left, creating a beautiful range of colors and shapes, we see an allegorical figure of a woman holding a bridle. Emblem books (fig. 3) of the period allow us to identify and to control one's desires and passions.

(emblem illustrating Temperance, page 35)

Gabriel Rollenhagen, Crispijn van de Passe

Published 1613

The use of paintings to comment on courtship and amorous relations is common in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century. Many such paintings refer to the difficulty of resisting the temptations of the flesh and the dangers of giving into passion, particularly under the influence of wine and tobacco. In the mid-seventeenth century artists such as Ter Borch and De Hooch created works with such content which undoubtedly influenced Vermeer.`

The rarity of Vermeer's paintings and the homogeneity of his work allow us to follow the development of his painting and observe the small variations evident in his pictorial and compositional techniques and his changing thematic interests over the years. In this painting, as in others of the late 1650s, the form in which the painter defines the space has changed in respect to earlier works: rather than directing the viewers gaze towards the area in which the main figures are located through objects placed in the foreground (as in, for example, Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, the figures here occupy a more open and deeper space.

The idea of locating the figures in a corner of a room recalls De Hooch (fig. 4), most of whose interiors use this device which undoubtedly influenced Vermeer. In the 1650s, just before he left Delft for Amsterdam in 1660 or 1661, De Hooch also became interested in the representation of light filtering through window panes, bathing the interiors with a light which is interrupted by the presence of the figures and objects. In paintings such as The Milkmaid, Officer and Laughing Girl, or the present work, the artist begins to use this device which would become such a famous feature of his style and which allowed him to make light the central element in his work.

Peter de Hooch

c. 1658

Oil on canvas, 73.7 x 64.6 cm.

The National Gallery, London

One of the most striking objects in this scene in terms of its beauty and the realism of its execution is the white jug (fig. 5) on the table. The wine which the gentleman is offering was undoubtedly poured from it, making it an element related to the licentious behavior which the painting criticizes. The portrait on the end wall, in contrast, shows an elegantly dressed man, a model of virtue which the artist juxtaposes with the two men in the painting. The golden lines of the picture's frame, highlighted by the light coming in from the window, call our attention to the role which this element plays in the painting's geometrical construction, always an important element in Vermeer's work.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1659–1662

Oil on canvas, 78 x 67 cm.

Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Brunswick

The most remarkable feature of the painting, though, is very puzzling, and this is the image in the stained-glass window (fig. 6). This has been identified as the coat of arms of Janetge Jacobsdr. Vogel, first wife of Moses van Nederveen, but it is unclear how Vermeer cam to know of it or incorporate it in this and the Brunswick paintings. Janetge Vogel died in 1624 and she and her husband lived at some distance from where Vermeer lived. It seems unlikely that Vermeer acquired an actual window made for Vrouw Vogel. On the contrary, he paints a window with identical leading but with plain glass in five other paintings and in a sixth with a different quasi-heraldic design. It is more probable that it was the imagery of that coat of arms that he wanted and adapted for this painting. In the two paintings in which this heraldic device appears, this Berlin painting and the Man offering wine in Brunswick, the window is open and the illuminated image dominates the picture. It is not so much part of the interior as an intrusion into it. It has an emblematic force.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1659–1662

Oil on canvas, 78 x 67 cm.

Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Brunswick

The female figure shown in the glass holding a square and a bridle personifies Temperance. It is fitting that this drama should be seen in such a light. Did Vermeer—and ter Borch—know that, according to Pausanias, the ancient Greek painter Pausias of Sikyon had won immortal fame by a picture of Drunkenness in which could be seen both the glass cup and the woman's face showing through it?

The painting in Brunswick also includes an identical stained glass window and, as mentioned above, may be seen as a variation of the Berlin painting. But it is a more problematic work. It is the only painting other than the Boston Concert to include three figures, but where the Concert shows two women and a man making music together, the third figure in the Brunswick painting is apart from the couple in the foreground. The obvious explanation is that, as his pose suggests, he, too, is a suitor for the young woman's favours but has been rejected. It is therefore understandable that his position is uncomfortable. In the eighteenth century his figure appears, to have been painted out. Overpainting and restoration may be responsible for a certain uneasiness in the principal figures, too. The proportions of the woman to her chair are, perhaps, a little odd; it appears, from the perspective of the floor tiles, as if she is sitting a little distance forward of the table, yet the gallant who bends over her to press on her the glass of wine appears to be standing beyond the white tablecloth. This painting and the very badly damaged painting of a Girl interrupted at her music in the Frick Collection are also exceptional among Vermeer's small multi-figure paintings in having a character meet the viewer's eye.