Vermeer's Neighborhood

(part one)

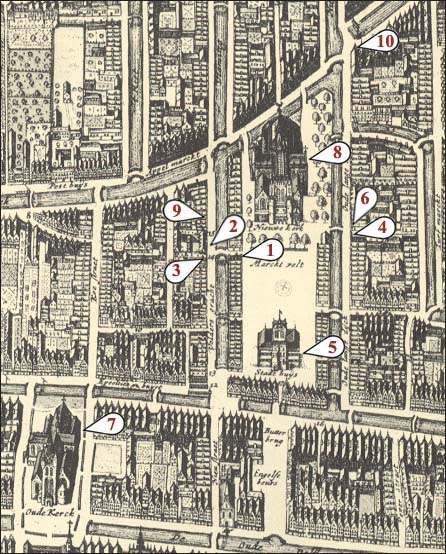

Below are listed ten significant points of interest which are related the life of Vermeer. These places can be located with relative security on the period map of Delft to the right. Delft's city plan has changed little through the centuries.

![]() To access detailed information and images of each Vermeer-related place, click on the name of the location below.

To access detailed information and images of each Vermeer-related place, click on the name of the location below.

| 1. | Mechelen | Vermeer's father's inn where the painter was born and raised |

| 2. | St. Luke's Guild | the guild of Delft's artisans and artists |

| 3. | The Little Street | the presumed location of Vermeer's Little Street |

| 4. | Maria Thin's House | Vermeer's mother-in-law's house & where Vermeer lived after Mechelen |

| 5. | Stadthuis | Delft City Hall |

| 6. | Jesuit Church | Vermeer's mother-in-law's house and Vermeer's residence |

| 7. | Oude Kerk | Delft's oldest parish church founded about 1246 and Vermeer's burial place |

| 8. | Nieuwe Kerk | second parish church of Delft founded in 1496 |

| 9. | 'Flying Fox' | Vermeer's birthplace and his father's inn |

| 10 | View of Delft by Fabritius | the point from which Fabritius painted his own View of Delft |

![]() for a complete version of the

for a complete version of the

map click on one of the two links below

1.140 KB / 240 KB

detail of Willem Blaeue's City Plan of Delft

from Joh. Blaeu's

Toonneel der Steden van de Vereenigde Nederlanden, 1649

The Blaeu family in Amsterdam was one of the great cartographic concerns of the seventeenth century, whose work was well-known throughout the Netherlands. In 1621, he and his sons took over from the sons of Balthasar Berckenrode (who himself was the son of Floris Balthasar, a prominent cartographer and long-time member of Delft’s St. Luke’s Guild) the printing of Berckenrode’s map of Holland and West Friesland, which appears in several Vermeer works. Blaeu’s sons published posthumously his 12 volume atlas of the world in 1663, in which he wrote: "Geography [is] the eye and the light of history…maps enable us to contemplate at home and right before our eyes things that are farthest away." This metaphorical but very epistemological connection between a symbolic representation of reality (maps) and one’s imagination was an important and recurring Vermeer motif. The 1648 Blaeu bird’s eye map of Delft you are using was again published posthumously by Blaeu’s son, Johannes.

Vermeer in Delft

In an age when every self respecting painter had to travel to Rome to verse himself in the immortal works of Raphael, Titian and Michelangelo, it is surprising to note that not one of the great masters responsible for the rise of Dutch painting felt the need to go to Italy. Esiais van de Velde, Jacob van Ruisdael, Frans Hals, Rembrandt van Rijn, Jan Steen and Johannes Vermeer all stayed in the Netherlands, close to their home painting for their local market.

Vermeer seems to have passed his entire life in his home town Delft, although it is known that he made a brief trip to Amsterdam and The Hague in his last years. Some experts believe that he studied painting in Amsterdam or in Utrecht although there exists no historical proof in regards. In any case, Vermeer must have loved his home town very much. His two "portraits" of Delft, the majestic View of Delft, a hymn to civic pride and nature, and the humble Little Street, which narrates the intimate life as seen across and inner-city canal, are tangible proof. It is known that Vermeer painted another landscape of Delft, a "view of a house standing in Delft" as it was described in the 1696 Amsterdam auction.

(the following is from The World of Vermeer: 1632-1675, Hans Koningsberger, New York, 1967)

Delft was the third city of Holland to receive a municipal charter in 1246 and it remained in, the forefront of Dutch history for several centuries. As well as being a center of resistance and headquarters for William of Orange during the war with Spain, it was the birthplace of William and one of the war's military heroes; Hugo Grotius, jurist and statesman who established the principles of international law; scientist Antony van Leeuwenhoek, one of the first microbiologists. When Holland began to flourish in the late 16th Century, Delft shared the new prosperity.

Then in the second half of the 17th Century (about the time Vermeer's ' career was beginning) as Amsterdam and Rotterdam, because of their excellent ports, took over more and more of the nation's trade, Delft slowed down. Its famous pottery industry continued to flourish, but other businesses languished. The number of breweries in the city shrank from more than 100 to 15. It became the home of retired people and a stronghold of conservative Calvinism. Gradually the once-vigorous city went into a decline that left it virtually dormant until the 19th Century.

The one lucky result of this misfortune is that the heart of Delft today looks very much as it did in Vermeer's day, since, by the time the town came to life again, men had learned to value and preserve the architectural heritage of the past. Thus Delft still has a few acres of houses, churches, canals and squares which lead us straight into Vermeer's world. In fact, a plan of Delft, published in 1648 by the map maker Willem Blaeu, so detailed that it shows Vermeer's house, is accurate enough to be used for a walk today.

A view of the Oude Kerk from

the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk.

The center of old Delft is the market, which is shown as a white oblong in the middle of Blaeu's plan. The market square is not particularly large, but it is dramatic because it is the only wide-open, ornamental space within a medieval huddle of houses. Old Delft, which had about 23,000 inhabitants in 1630, actually boasts only three or four real streets; the rest are alleys and canals. The canals were the arteries of Delft, carrying its trade and also its visitors; in fact, Holland's waterways were its safest and smoothest channels of transportation until well into the 19th Century. Marcel Proust described one such waterway after visiting Deft: "An ingenious little canal dazzled by the pale sunlight; it ran between a double row of trees stripped of their leaves by summer's end and stroking with their branches the mirroring windows of the gabled houses on either bank."

The light of Delft on houses reflected

in one of the numerous canals.

Now these narrow canals lie quiet under their humpbacked bridges, but they are still used to carry supplies to the flower market, the butter-and-cheese market and the fish market, all located along the waterside. They are almost straight, but their slight bends provide surprising changes in the fall of the light, which is confined by the houses, reflected in windows and water and sifted through the canopy of the trees.

The light of Delft! Thousands of words have been written about it and its real or imagined secrets. The French playwright and poet Patil Claude wrote that it was "the most beautiful light in, existence." Considered coldly, there is no reason why the light of Delft should be different from the light of The Hague or Rotterdam. But the old town is so still, even today the heavy foliage, the dark water and the old brick walls envelop it so beautifully that its light, many times reflected and filtered, does seem different once it has reached the level of the eye; it seems to have an especially soft, fluid quality.

A view of the Voldersgracht, the small street

where Vermeer was born.

Perhaps it is not only Delft, not just the trees or canals, which make this light so special, but also Vermeer. As Stratford-on-Avon or Walden Pond may move the visitor in a manner which has nothing to do with their physical appearances, so the light of Vermeer' s town has been given a magical connotation by his work.

The View of Delft

(by Mariët Westermann)

Vermeer's View of Delft is probably the most memorable cityscape in western art. Though not an interior scene, as most works by Vermeer are, the painting draws us into his mental and social world: into his artistic vision and into his city. What we see seems almost too obvious, too plainly descriptive, too perfectly observed to require comment or analysis: the city of Delft appears before us under the partial clouds characteristic of the North Sea climate, a palpable grouping of brick, mortar, and clay structures seen across the broad Schie canal. It is all there, still nameable today: the Schiedam gate at left, the Rotterdam gate with its twinned turrets at right, the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk, or New Church, picked out in the brightest sunlight, the diminutive tower of the Oude Kerk, or Old Church, just breaking the long roofline at left. The scene's varied light effects look so natural -deep shadow and bright patches, pinpoint highlights and watery reflections -that the eye ignores what the mind knows: that this light is high artifice, that it is a work of painting.

Despite the unusualness of this exterior scene within Vermeer's production, it has, for many modern viewers, come to stand for Vermeer himself. When Marcel Proust needed an image for artistic perfection he chose the patch of yellow that, in Vermeer's curious vision, wedges a splendid sun-drenched roof between shaded walls. How could the View of Delft become an epitome of artistry in western culture? Some answers to this question tell us more about the novel and self-aware character of Vermeer's art, which is so central to the continuing appeal of his interior painting.

Art historians have traced various precedents for Vermeer's direct rendition of the city from the south side, and the painting unquestionably acknowledges this genealogy. Vermeer knew the descriptive profile views of cities that appeared in historical descriptions of cities. Such views were often printed alongside the edges of city maps, and Vermeer included a wall map of this kind in the Art of Painting). He also must have known paintings of cities seen in profile against a low horizon. Yet unlike the cityscapes Vermeer found before him, View of Delft does not amount to a somewhat clinical, dry inventory of the local architectural scene. There is an unprecedented immediacy and tangibility about Vermeer's Delft.

Much accounts for the difference the View of Delft makes. Crucial is the framing, which cuts off the view to left and right at seemingly arbitrary points. Eyes trained on photography accept such slicing, but it must have been startling to contemporaries. This move brings the city closer, makes it loom large. Another tactic that makes the city seem monumental yet near is the remarkably high key of the coloring of distant architectural features. While the colors are limited in range, their intense saturation is surprising given the presumed distance at which the city is seen. And then there is the strong composition of the painting into broad but loose horizontal bands of light and dark, unobtrusive at first. Insistent patterns also arise from Vermeer's judicious distribution of sunlight and shadow, and from his emphasis on dark foreground clouds and dark reflections in the water.

The result is an arresting monument to Delft and its historical place, signaled subtly by the sunlit aspect of the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk. This church had gained fame in the 17th-century as the location of the tomb of William of Orange, the 16th-century prince who had led the Northern Netherlands in their revolt against Spanish governance. The Father of the Fatherland, as he became known, had chosen Delft as his residence, and it was there, in 1584, that a political adversary assassinated him. Most Delft contemporaries would have recognized Vermeer's emphasis on the tower, in marked contrast to the diminutive presence of the tower of the Oude Kerk. And yet View of Delft is no Orangist propaganda piece, for the image subsumes the venerable and complex history referenced by the tower into an image that looks contingent on an immediate atmospheric moment. Most of Vermeer's paintings derive their fascination from such a tension between acute momentary observation (registered in accidents of lighting or human actions) and a sense that the resulting image freezes a moment in a narrative history.

from:

Mariët Westermann, "Vermeer and the Interior Imagination." in Vermeer and the Dutch Interior, Alejandro Vergara, Madrid, 2003, p. 219