By February 1629, Reynier Jansz. Vos (Vermeer's father), his wife Digna, and his daughter Gertruy were living in an inn on Voldersgracht (Fuller's Canal) called De Vliegende Vos (The Flying Fox). Reynier's move away from the inn called Three Hammers located on Beestenmarkt (Small Cattle-Market) was a move to a higher social status and a gamble to make a better life for his family. We know of a second rental contract on Voldersgracht dates from 1637 (the first contract is lost). Reynier's landlord was a leather dealer and shoemaker, Pieter Corstiaens Hoppers, economically successful but almost illiterate.Kees Kaldenbach, Vermeer and Delft, accessed October 29, 2023. In 1641, when Vermeer was nine years old, the lease of the Flying Fox ran out but Reynier was able to move to Mechelen, a much larger tavern on the Markt (Market Square), indicating that the Flying Fox had brought some fortune to the hard-working father. The Voldersgracht still runs parallel to the north of the Markt, the civic and spiritual heart of Delft.

Where did the name of Reynier's inn come from? In the documents, Vermeer’s father mostly called himself Van der Minne, after his stepfather, or Vos (fox), as the animal also depicted on the signboard of his inn—possibly a nod to the medieval animal tale "Vanden vos Reynaerde""Vanden vos Reynaerde," also known as "Van den vos Reynaerde," is a significant work in Middle Dutch literature, likely written in the late 12th or early 13th century. It's an epic poem that tells the story of Reynard the Fox, a cunning trickster who uses his wit to deceive other anthropomorphized animals in a satirical depiction of human society. Through its characters—such as the noble lion king, the gullible bear, and the conniving wolf—the poem critiques social and political structures, particularly the church and feudal system. The Reynard stories were widespread in Europe, adapted into various languages and formats, and have left a lasting impact on European folklore, literature, and even the Dutch language with phrases and expressions derived from the tales. Reynard remains a symbol of craftiness and cleverness in popular culture. or Reynard the Fox, because of his own first name. He only used the surname Van der Meer or VermeerThe use of the prefix "ver" in Vermeer’s name as a contraction of "van der" originally occurred mainly in the Southern Netherlands—which his son would later make famou—in documents from September 1640. Both spellings fit into a long Dutch tradition of names that indicate where the name bearer comes from (the so-called origin names) or where they live (locative names). Apparently, the family preferred to associate themselves with the topographic word "meer," which traditionally could mean either a still inland water or the sea.Pieter Roelofs, "Johannes Vermeer," in VERMEER, ed. Pieter Roelofs & Gregor Weber, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2023, 28.

The Voldersgracht canal was named after a profession carried on here in the Middle Ages. "Volders" ("fullers" in English) were textile workers, who prepared wool and other materials with their feet to make it into cloth. The process involved using urine and Fuller’s earth, after which the "fulled cloth" was rinsed in the canal. A dirty job—not good for the brewers, who had to use the same water. When Delft expanded in the fourteenth century, the fullers had to leave. By Vermeer’s time, Leiden had overtaken Delft as the textile capital of Holland. Textile working did not disappear from the city overnight, but it was certainly no longer the driving force behind the city's economy. By the seventeenth century, many fullers were probably looking for other occupations.David de Haan, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Babs van Eijk, and Ingrid van der Vlis, Vermeer's Delft (Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, Museum Prinsenhof Delft, 2023), 119.

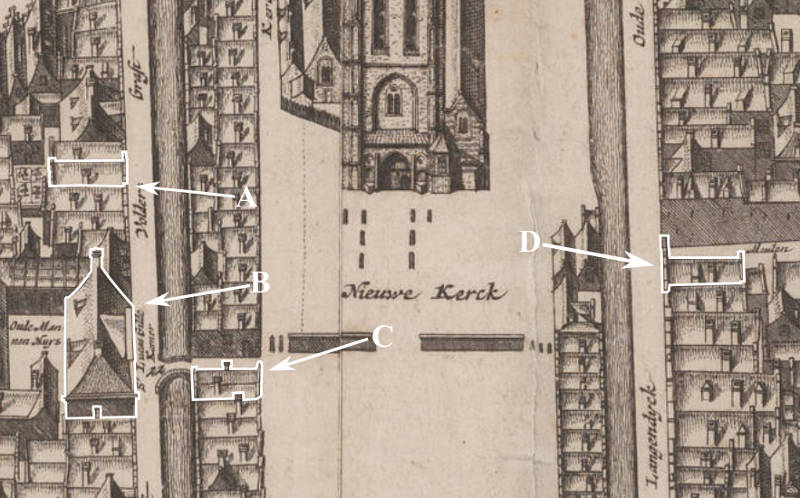

A. Flying Fox (Vermeer's presumed birthplace and inn of his father)

B. The Delft Guild of Saint Luke (professional organization of artists and artisans)

C. Mechelen (a large tavern on the Market Square rented by his father where Vermeer and his family lived after the Flying Fox)

D. Groot Serpent(studio & living quarters where Vermeer resided with his wife, children, and mother-in-law, Maria Thins?)

E. Trapmolen (studio & living quarters where Vermeer resided with his wife, children, and mother-in-law, Maria Thins?)

The area around Voldersgracht was more respectable than the Beestenmarkt, where mostly working-class folk lived. Among the neighbors on Voldersgracht was Cornelis Daemen Rietwijck (c. 1590– 1660), a Catholic portraitist who operated a drawing school a few houses away from the Flying Fox. At this school, youngsters were taught the first principles of painting, which included drawing from prints, drawings, and plaster models. Additionally, they received a basic education in mathematics and other subjects. Rietwijck's library comprised devotional literature, travel books, and historical accounts, as well as a copy of Karel van Mander's 1604 Het Schilderboeck (The Book of Painters), which in those days was considered the bible for painters.Pieter Roelofs, "Venturing into Town," in VERMEER, ed. Pieter Roelofs & Gregor Weber, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2023, 28.

A few doors down from The Flying Fox, Pastor Jacobus Taurinus (1576–1618) lived with his wife Margaret van der Meer (no relation to the artist's family). There were richer people in Delft than the pastor and his wife on Voldersgracht, but those two stood on the highest rung of the town's society. Reynier's immediate neighbor was Cornelis van Schagen, a well-to-do merchant who sold cloth from the shop in the lower part of his house. Reynier may have not been well-off as some of his neighbors; keeping an inn, moreover, was scarcely a prestigious occupation. But it was much better than weaving caffa (caffa is a damasked fabric containing silk and either wool or cotton) by the side of the Beestenmarkt."John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 65.

It has been recently discovered was that Maria de Knuijt (died 1681), the wife of Vermeer's only known patron Pieter van Ruijven (1624–1674), grew up a few houses away from the Mechelen inn whose backside looks on to Voldersgracht, were her father owned two houses. Although she was nine years older than Johannes and already seventeen when he moved to the Markt at the age of eight, she was only three years older than his elder sister, Gertruy. Maria would have been familiar with the Vermeer family from their early years on the nearby Voldersgracht. She likely saw Johannes playing in the neighborhood as a young boy and, along with Gertruy and Johannes, would have been among the local residents who witnessed grand events on the market square, such as the funeral of Prince Frederik Hendrik in 1647.Pieter Roelofs, "Venturing into Town," in VERMEER, ed. Pieter Roelofs & Gregor Weber, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2023, 33.

Inns

In the seventeenth-century Netherlands, inns were central to the social, economic, and cultural life. They provided not only lodging, food, and drink but also venues for business transactions, social gatherings, and the exchange of news. As some of the few public spaces where people from different social strata could mingle, inns played a unique role in society. Often, they held auctions—including those for artworks—which contributed to the thriving Dutch Golden Age art market. Inns were also popular sites for entertainment, hosting plays and musical performances..

Some inns were respectable and some were little more than brothels. Visitors from abroad weren't always able to tell the difference at first glance. Obviously, beer was drunk in both types of inns. Certainly, beer would have been one of the principal calling cards of Reynier's new venture. Delft was a beer town renowned for its high-quality production, which, however, had waned by the time of Vermeer. Beer production requires clean water and Delft was known for its excellent supply of water and for its proverbial cleanliness. In the Netherlands, beer was drunk at all hours although it was generally much weaker than today's beer. It is said the average beer-drinker in Delft put away 250 liters a year. Beer was drunk at all times of the day from breakfast on.

The Flying Fox

Reynier's talents were many: he ran The Flying Fox, dealt in paintings, and was also known as a caffawerker. Caffa was a damasked fabric containing silk and wool or cotton used especially in upholstery production. Perhaps the daily presence of this luxurious fabric stimulated in the young lad Johannes a fascination for the delicate sheen and joyful play of light, one of the hallmarks of his compositions.

Johannes was presumably born in the Flying Fox and it is only logical that the constant ebb and flow of visitors of all walks of life, including accomplished painters, as well as the pictures hung on the walls of his father's inn, must have kindled the first flicker of his future artistic calling. He heard the banter of artists' shop talk every day and was introduced into the mystery of the painter's craft. The powerful Guild of St Luke, which regulated the lives of all Delft artisans and artists, was only a few paces to the right of the Flying Fox.

There must have been no lack of music in and around the Flying Fox. Every day, Johannes heard the hourly chimes and weekly concerts of the carillons of the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church) whose imposing tower cast its long shadow over the inn on sunny days. Vermeer's grandfather was a musician and had owned more than one musical instrument.

It is not certain exactly where the former location of the Flying Fox was located. John Michael Montias, Vermeer's chief biographer, believed that it was "two houses east of the Oude Mannenhuis ( Old Mens Home)," making it number 23. From 1620–1640 changes had been made just in the row of houses at 23–27 (fig. 1 & 2). No doubt, buildings had been joined and then split into still other lots.

However, recent considerations by the team of investigators Ingrid van der Vlis, Steven Jongma, Wim Weve, and Bas van der Wulp have narrowed the range of civic number to two. The difficulties arise because during the seventeenth century, there were no house numbers; homes were identified by their name or by their position in relation to a well-known landmark. Vermeer's birthplace was described as the "fourth house to the east of the Oude Mannenhuis" (an alms-house for elderly men). Historical data in the land registry map pinpoint that Vermeer's birth house corresponds to the current plot of numbers 25 and 26. According to the team, number 25 still retains the structure of the seventeenth-century building, including original wooden beams with paintwork from Vermeer's time. The house had an extension where number twenty-six now stands, but it's unclear exactly where within these premises Vermeer's crib was situated.Ingrid van der Vlis, Steven Jongma, Wim Weve, and Bas van der Wulp, "In the Footsteps of Vermeer," in Vermeer's Delft, edited by David de Haan, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Babs van Eijk, and Ingrid van der Vlis (Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, Museum Prinsenhof Delft, 2023), 117.

While the precise spot where the Flying Fox once stood may elude us indefinitely, a stroll along the Voldersgracht has the power to whisk even the most world-weary traveler straight into the essence of Vermeer's Delft. On a day when the streets whisper quietude, it is difficult to resist the pull of its bygone charm. The accompanying photograph (fig. 2), captured from the lofty perch of the Nieuwe Kerk's tower in the embrace of summer, casts the church's shadow momentarily across the faithfully restored Guild of Saint Luke. Dominating the view to the right, the edifices labeled as civic numbers 25 and 26 on Voldersgracht emerge, evoking the rich historical tapestry of the area.

Was the scene of Vermeer's Little Street located at Voldersgracht?

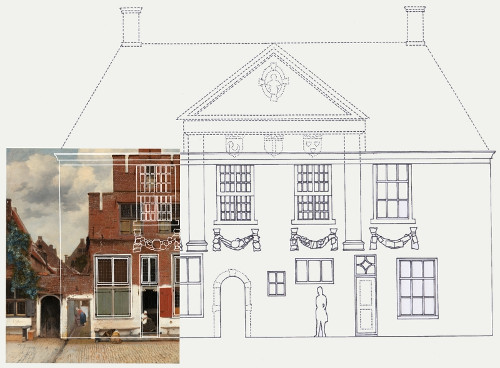

Although many locations have been proposed in the past, the most consistent candidate for the location of the scene of Vermeer's The Little Street has been the Voldersgracht, a narrow street that runs next to a canal in the center of Delft, where Vermeer was born. However, some art historians believe that despite the scene's realistic appearance, it could be a distillation of typical architectural elements gathered and adroitly woven together within the privacy of the artist's studio.

The century-old question was recently addressed by Dr. Frans Grijzenhout, professor of Art History at the University of Amsterdam. Grijzenhout argues that the setting of the painting is on Vlamingstraat (fig. 3) in Delft, where houses 40–42 now stand. Grijzenhout's conclusion is based on measurements he has found in the Legger van het diepen der wateren binnen de stadt Delft (Ledger of the dredging of canals in the town of Delft), a document compiled from 1666 onward recording the widths of house frontages for tax purposes.

On the other hand, Philip Steadman, the London architect and author of Vermeer's Camera: Uncovering the Truth behind the Masterpieces, examined point for point Grijzenhout's hypothesis and found a number of inconsistencies. Steadman holds that Grijzenhout's proposal is unfounded and provided detailed information in support of the Voldersgracht solution (fig. 4).

Click here to read Steadman's arguments supported with contemporary maps, drawings and a nineteenth-century photograph.

Grijzenhout mused that the house on Vlamingstraat would have had particular resonance for Vermeer, since the house was occupied at this date by Ariaentgen Claes van der Minne, one of Vermeer's aunts. But Steadman suggests that Voldersgracht would have held greater meaning for the painter in that it was a view from his family home, across to a building, which, when he painted The Little Street, was just about to be converted for use by his profession's center, the Guild of Saint Luke.

Click here to read Grijzenhout's arguments or see: Frans Grijzenhout and Lynne Richards, "Vermeer's 'Little Street': A View of the Penspoort in Delft," Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam 2015.