Primary resources are firsthand evidence or documentation directly related to artworks, artists, or specific periods in art history, playing a crucial role in gaining a comprehensive understanding. By collecting primary sources related to Johannes Vermeer's life and art, this study seeks to shed light on his historical context, explore critical reception of his work and enable comparisons with contemporaries. These sources not only reveal the cultural significance of Vermeer's art in his era but also its enduring influence on art history. These resources include:

- Artworks themselves: Paintings, sculptures, installations, and other art forms serve as direct evidence of artistic styles, techniques, and themes from various periods.

- Artists' writings: Diaries, letters, manifestos, and interviews where artists discuss their work, processes, and intentions.

- Contemporary documents: Critiques, reviews, and commentary published during the time an artwork was created or an art movement was active.

- Official records: Documents such as auction catalogues, museum records, legal depositions, and estate inventories.

Secondary resources, in contrast, analyze, interpret, or critique primary sources and events, offering insights one step removed from the original artworks or historical events. They also encompass peer-reviewed publications that feature research articles, theoretical papers, and reviews of current art historical scholarship. Secondary resources are crucial for understanding the broader implications of art and art movements by providing context, analysis, and varied interpretations.

Primary resources provide direct evidence of the past, while secondary resources interpret or analyze that evidence to deepen our understanding of art and its historical context. Thus, primary resources offer a direct glimpse into the past, while secondary resources aim to understand, interpret, or critique artworks and art historical events.

This article greatly benefits from the contributions of John Michael Montias, an American economist and leading biographer of Vermeer, who crafted the most comprehensive portrait of the artist thus far. Through diligent research in the Delft Municipal Archives, Montias combined his passion for the subject with scholarly rigor to uncover new, significant documents. He also reexamined existing documents with fresh insights, shedding light on the Delft master and those who interacted with him in any capacity. "Through his scrupulous analysis of various documents ranging from notes and letters to receipts and legal papers,…Montias "unveiled the layers of Vermeer's life, a favorite and enigmatic artist of his, and one of the world's most mysterious. His work opened the door for a new genre of art history in which artists were analyzed in the context of their social and economic surroundings and not merely their works. "Kathryn Shattuch, "John Montias, 76, Scholar of Economics and of Art, Is Dead," The New York Times, August 1, 2005, accessed November 15, 2023.

Vermeer-Related Primary Resources

- Veen, Otto van. Amorum Emblemata, figuris aeneis incisa. Antwerp: Henrik Swingen, for the author, 1608.

- Record of Vermeer's Baptism: October 31, 1632 | Delft. Nieuewe Kerk (New Church) - Baptismal Register no. 12.

- Leonaert Bramer's Appeal to Maria Thins: April 4, 1653.

- Record of Vermeer's Marriage to Catharina Bolnes: April 5, 1653.

- Vermeer and Gerrit ter Borch Witness an Act of Surety: April 22, 1653.

- Guild Book of Delft Master Painters, Engravers, Sculptors, Potters, etc. in the Seventeenth Century. December 29, 1653.

- "Vermeer is Mentioned as a "Master Painter.": January 10, 1654.

- Declaration Concerning Johan van Santen with the Signatures of Johannes Vermeer and His Wife, Catharina Bolnes: December 14, 1655.

- Vermeer and His Wife Catharina Bolnes Contract a Loan of 200 Guilders from Pieter van Ruijven: November, 30, 1657.

- Johannes Vermeer Leases Mechelen: January 4, 1672.

- Vermeer's Family Leaves Nothing to the Camaer van Charitate: December 16, 1675.

- Vermeer's Funeral Casket is Held by 14 Pallbearers: December 16, 1675.

- Monconys, Balthasar de (1611–1665). 2 vols., Lyon, 1665–1666.

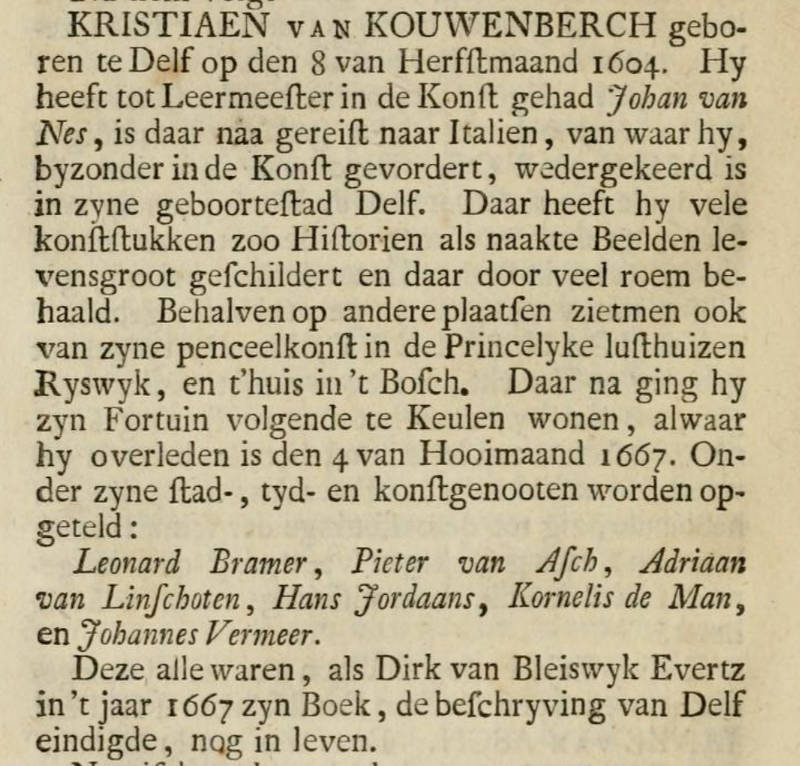

- Bleyswijck, Dirck van. Beschryvinge der stadt Delft. Printed by Arnold Bon, bookseller on the Marct-velt, Delft, vol. 1 and 2, Delft 1667 and 1680.

- Van Berkhout, Pieter van Berkhout - Fragments of the diary of Pieter Teding van Berkhout, Koninklijke Bibliorheek, The Hague. May 14. 1669.

- Sysmus, Jan (Johannes). Schildersregister (Register of Painters). 1669–1678.

- Lairesse, Gérard de Lairesse. Groot schilderboek (The Great Book of Painting). 2 volumes. Amsterdam: Willem de Coup and Petrus Schenk, 1707.

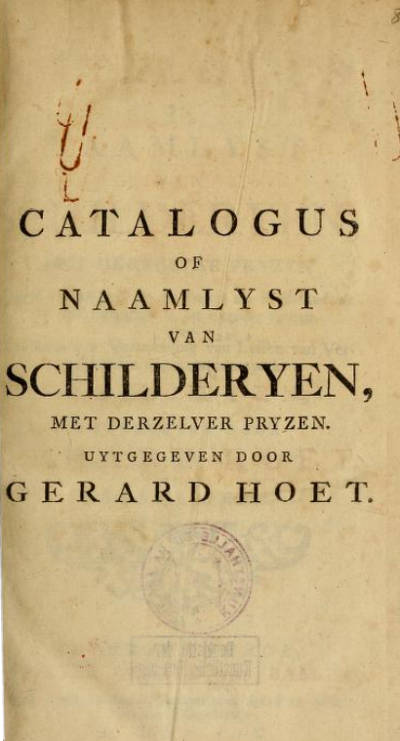

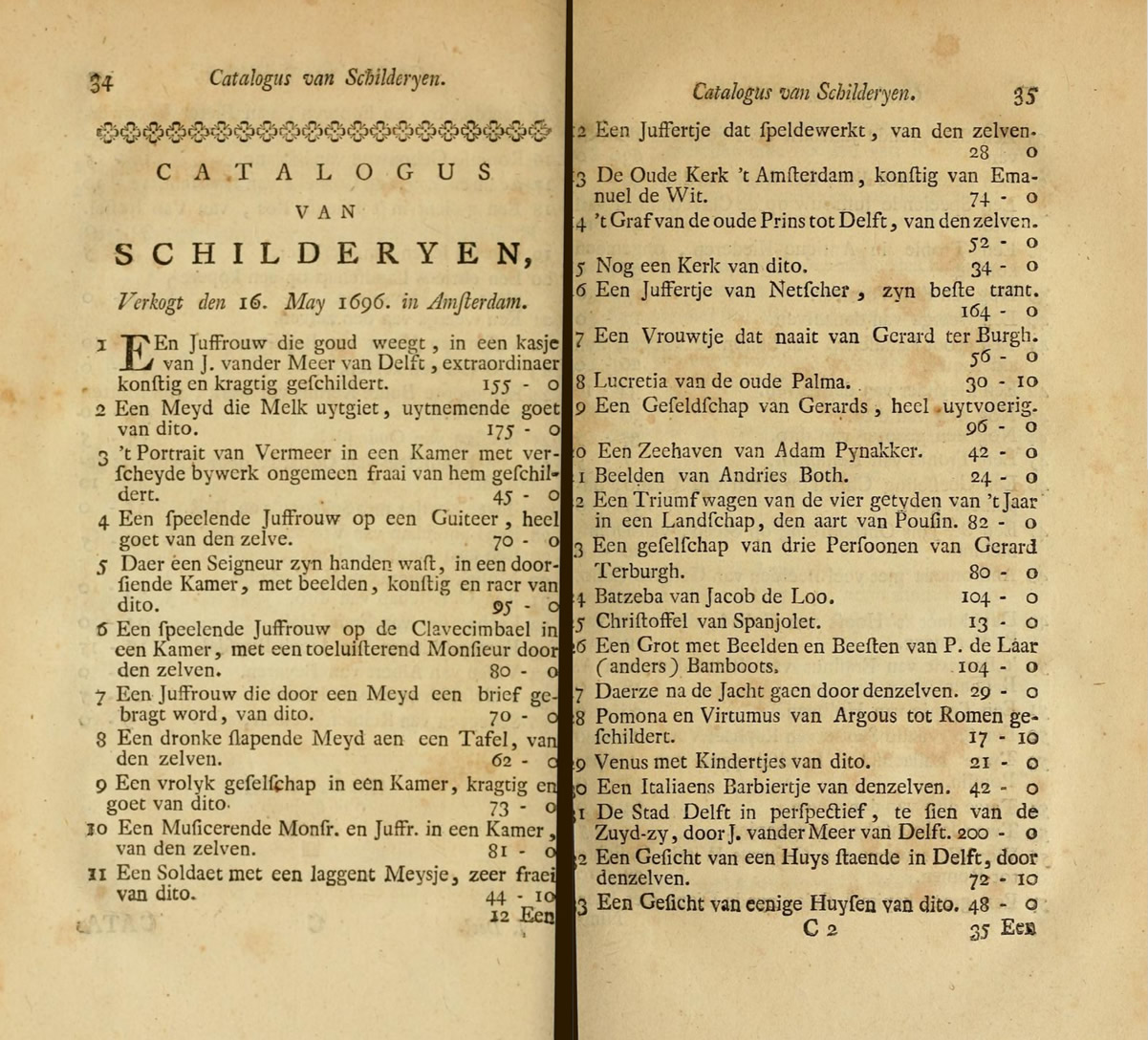

- Hoet II, Gerard. Catalogus of naamlyst van schilderyen met derzelver pryzen, zedert een langen reeks van jaaren zoo in Holland als op andere plaatzen in het openbaar verkogt, benevens een verzameling van lysten van verscheyden nog in wezen zynde cabinetten. 3 vols. The Hague, 1752–1770.

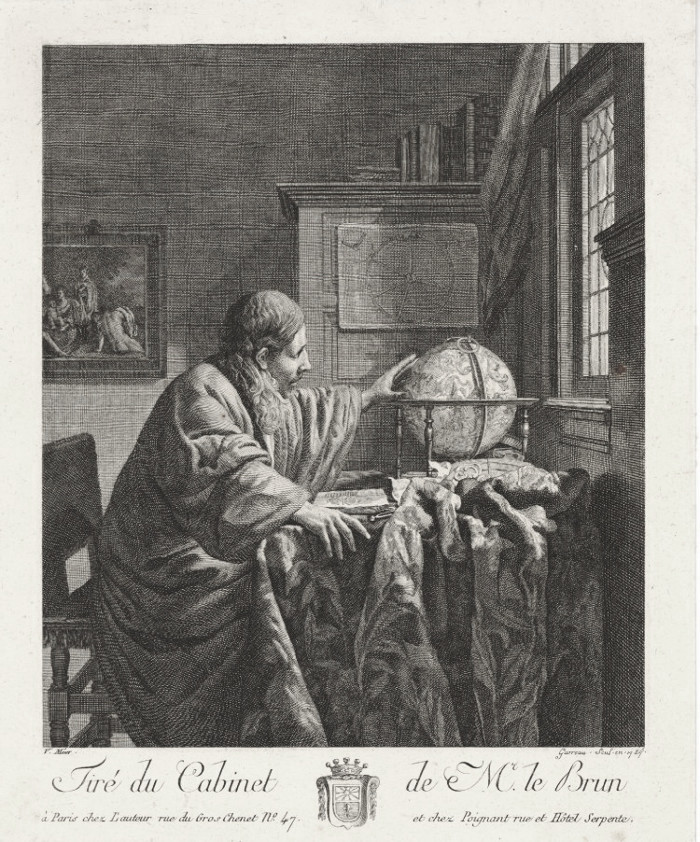

- Le Brun, Jean-Baptiste Pierre. Galerie des peintres flamands, hollandais et allemands, Paris, 1792–1796.

- De Vries, Jeronimo. Notes on Vermeer, 1813.

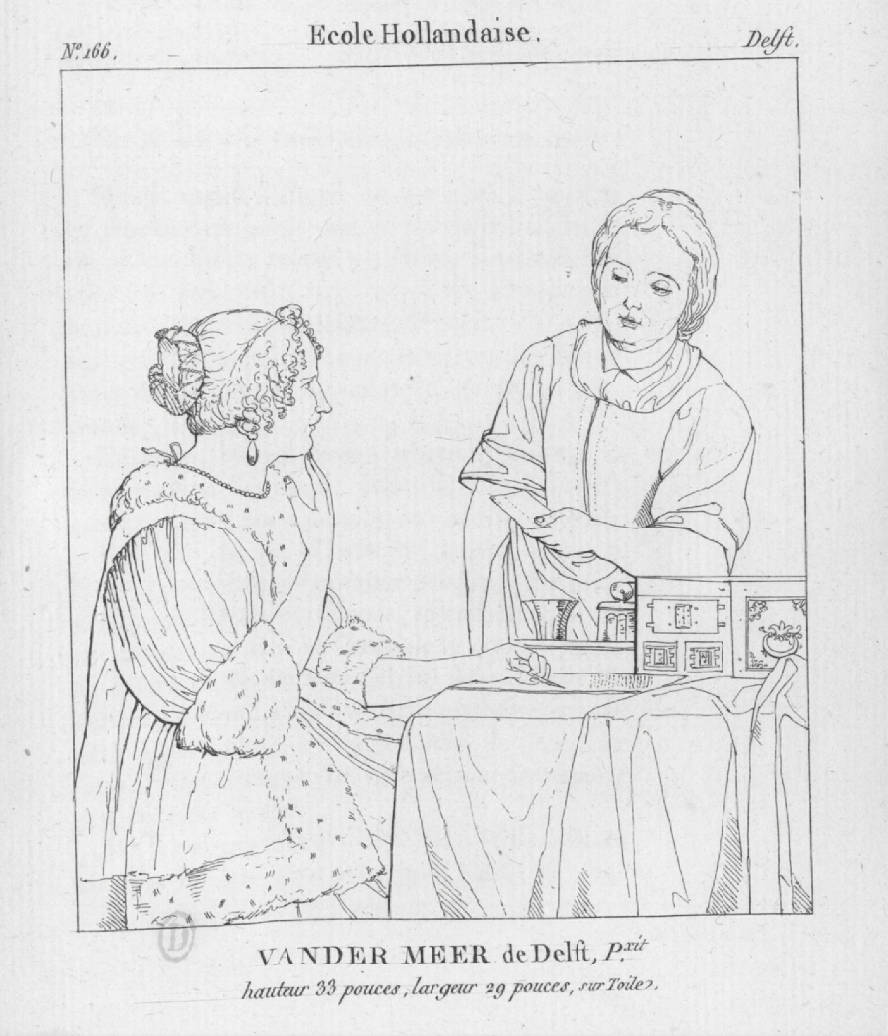

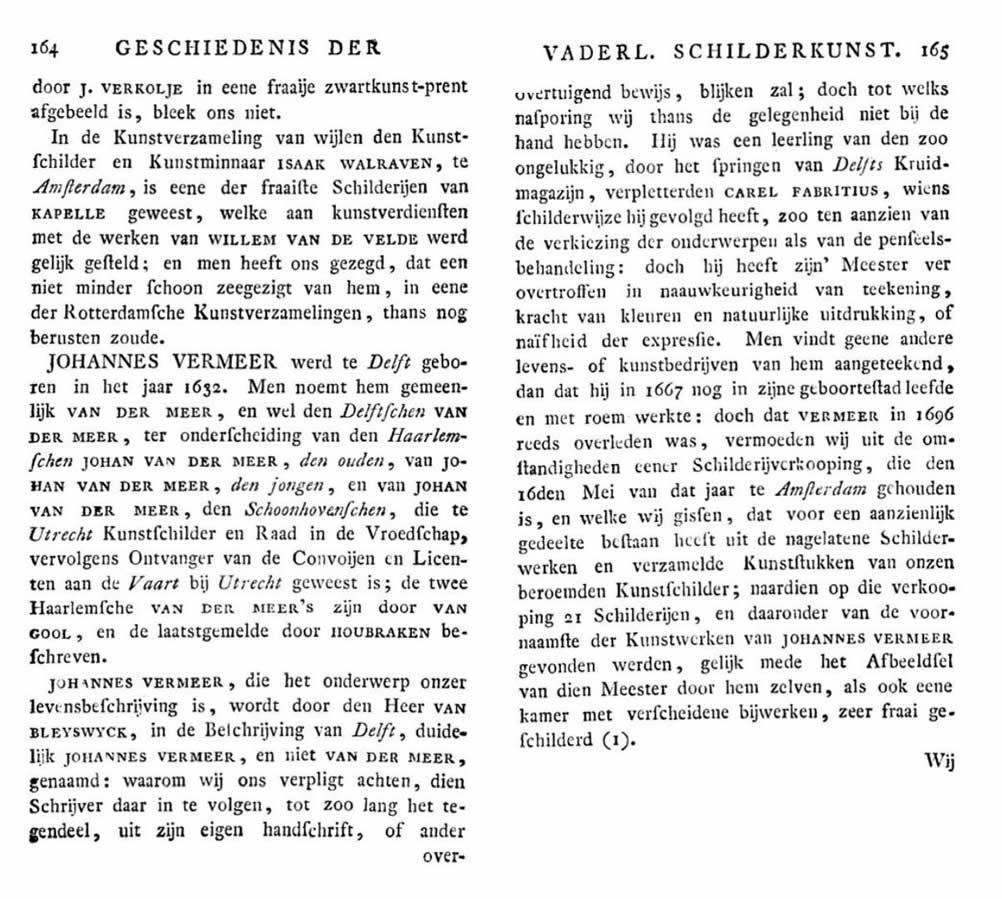

- Van Eynden, R. and Van der Willigen, Adriaen. Geschiedenis der vaderlandsche schilderkunst : sedert de helft der XVIII eeuw. 4 vols., Haarlem 1816–1840 (Volume 4, 1816, pp. 164-168).

- Josi, Christiaan. Collection d'imitations de dessins d'après les principaux maîtres hollandais et flamands. Amsterdam and London: Chez C. Josi, 1821.

- Smith, John. A catalogue raisonné of the works of the most eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French painters. Supplement vol. 9, London, 1842.

- Théophile Thoré, Etienne Joseph, "Van der Meer de Delft," Gazette des Beaux Arts, Oct. 1, 1866, pp. 297–330; Nov. 1, 1866, pp. 458–470; Dec. 1, 1866, pp. 542–575).

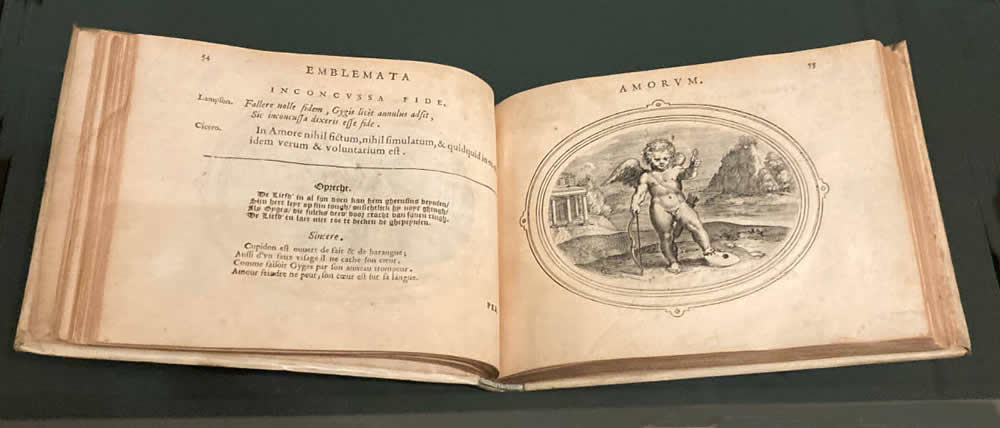

Veen, Otto van. Amorum Emblemata, figuris aeneis incisa. Antwerp: Henrik Swingen, for the author, 1608.

Otto van Veen, also known as Otto Venius (1556–1629), was a Flemish painter and humanist, active in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. He is best known for his literary works in the Southern Netherlands and for being Peter Paul Rubens' teacher.

Van Veen's Amorum Emblemata is considered to be one of the most important and influential of all emblem books. This work is significant for its combination of images and poetry, serving as a source of inspiration for artists and writers of the time. The collection was designed by Van Veen and first published in Antwerp in 1608 in three polyglot versions: Latin, French, and Dutch; Latin, Italian, and French; and Latin, English, and Italian. Its success and popularity led to many further editions and adaptations, while its images were subsequently used by decorative artists throughout Europe. In producing a book of love emblems, Van Veen was following a trend which began in Amsterdam in 1601 with the publication of Quaeris quid sit Amor, a compilation of twenty-four love emblem prints produced by the artist Jacques de Gheyn with accompanying Dutch verses by Daniel Heinsius. Van Veen's volume is far more comprehensive, consisting of 124 emblems."Otto van Veen: Amorum Emblemata," Special Collections Department, Library, University of Glasgow, acessed February 14, 2024.

An emblem book usually consists of three parts for each entry: an icon; a motto; and an epigram, or text (fig. 1). The icon image is designed to visually represent the central theme or idea of the emblem. The motto is a brief phrase or inscription, often in Latin, serving as a title or summary of the emblem's theme. This motto frames the viewer's interpretation of the image. The epigram poem, prose, or explication that accompanies the image and motto, elaborating on their meaning, often in a moral, philosophical, or allegorical context. Such books were immensely popular among all social classes, and according to the Dutch poet and writer Jacob Cats (1577–1660), their use is that they show "mute pictures which speak…humorous things that are not without wisdom; things that men can point to with their fingers and grasp with their hands."

Otto van Veen

Engraving, 16.5 x 21 x 2.3 cm.

Antwerp, 1608

Artists found a vast repository of symbols, themes, and narratives in emblem books. The complex interplay of text and image in these books provided a fertile ground for artistic inspiration, enabling artists to draw from a shared cultural vocabulary of symbols and meanings. This practice encouraged a more nuanced and layered approach to visual storytelling, where paintings and sculptures were imbued with deeper symbolic and moral dimensions.

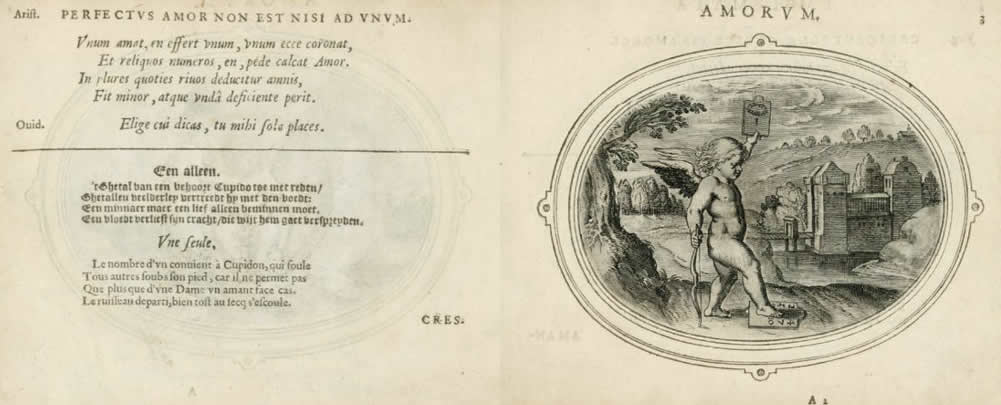

Dutch art historian Eddy de Jongh was the first to identify the likely inspiration behind the ebony-framed Cupid with a raised arm in Vermeer's A Lady Standing at a Virginal (fig. 2)—an engraved motto contained in Van Veen's Amorum Emblemata, "Perfectus a mor non est nisi ad unum" (Love is not perfect except to one) (fig. 3). In Vermeer's painted version, Cupid holds aloft a small card bearing the Roman numeral "I," referring to the emblem's caption. De Jongh suggested that Vermeer's inclusion of this motif likely alludes to the concept of fidelity in love, although he notes that it remains unclear whether the admonition is directed towards the standing musician or the spectator. Interestingly, the card held by Cupid in Vermeer's painting is blank, which, if intentional, may have further nuanced the story's meaning. However, the numeral may have degraded over time or been removed during previous restorations.

Otto van Veen

Engraving, 16.5 x 21 x 2.3 cm.

Antwerp, 1608

J ohannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1674

Oil on canvas, 51.7 x 45.2 cm.

National Gallery, London

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1657–1659

Oil on canvas, 83 x 64.5 cm.

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

Additionally, the Cupid not only bears resemblance to Van Veen's engraving but also resembles standing puttos first identified by German art historian Gustav Delbanco in 1928. Delbanco observed similar figures in the classicist works of the Alkmaar artist Cesaer van Everdingen (1616/17–1678), a prominent history painter of the time. While art historians continue to endorse Delbanco's claim with some reservations, the repeated depiction of the same painting, which unfortunately has not survived, over a long period makes it highly probable that Vermeer had access to this contemporaneous work, as he depicted other two other paintings, likely owned by his mother-in-law, Maria Thins, in his works over the years.

For more than 250 years, Vermeer's Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (fig. 4) was seen standing in front of a bare gray wall. Following the painting's restoration between 2017 and 2021, a meticulous restoration procedure uncovered the Cupid, making it starkly visible once again. The existence of an overpainted picture-within-the-picture had been known about since 1979. What is new is the discovery that the overpainting of the Cupid picture was not done by Vermeer himself.

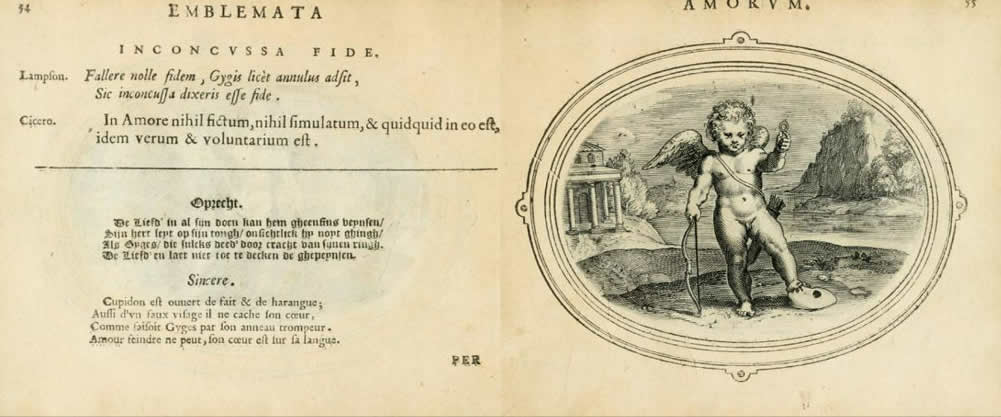

Differences in detail between the Dresden Cupid and the last version in A Lady Standing at a Virginal have led art historians to contemplate the exact nuance of meaning of the Cupid painting in the Dresden piece. The newly revealed Cupid portrays the figure striding forth triumphantly, trampling over one of two masks cast upon the ground—details conspicuously absent in A Lady Standing.In an earlier work, A Maid Asleep, one of the masks had been depicted as a pile of debris. The iconographical significance of the Cupid is believed to be inspired by another emblem in Van Veen's Amorum Emblemata, "Inconcussa fide," where Cupid is depicted in a similar posture (fig. 5). "Inconcussa fide" is a Latin phrase that translates to "Unshakeable Faith" or "Unwavering Trust" in English. It conveys the idea of steadfastness, reliability, and trustworthiness. Thus, in the specific context of Vermeer's Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window. Thus, the Cupid in Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window likely symbolizes the enduring and sincere nature of true love, steadfast and trustworthy in the face of challenges or temptations. One notable exclusion in Vermeer's rendition is that in Van Veen's emblem Cupid holds up the ring of Gyges in his raised hand, a detail possibly obscured by the curtain in Vermeer's painting. According to legend, the ring renders its wearer invisible. According to the text associated with Van Veen's emblem, true love transcends deceitful games, being founded on sincerity and honesty.

Engraving, 16.5 x 21 x 2.3 cm.

Antwerp,figure 1608

Whatever its meaning, Van Everdingen's work must have held significant importance for the artist, as it appears in the background of earlier works, such as A Maid Asleep and Girl Interrupted in Her Music, in different guises—a total of four times—making it one of Vermeer's favorite props..

Therefore, Vermeer's Cupid painting was likely not an artistic fabrication but a real painting mentioned as "a Cupid" in the inventory of his widow's possessions in 1676.

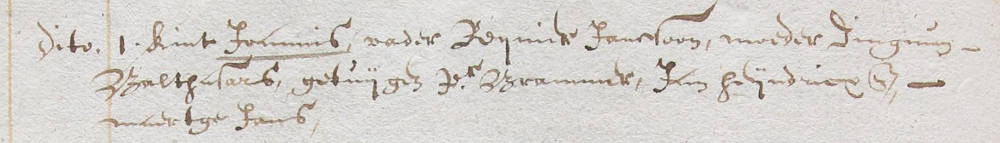

Vermeer's Baptism: October 31, 1632 | Delft. Nieuewe Kerk (New Church) - Baptismal Register no. 12

![Nieuewe Kerk (New Church) - Baptismal Register no. 12, October 31. 1632) <em> dito. 1 kint Joannis, vader Reynier Janssoon, moeder Dingnum Balthasars, getuijgen P[iete]r Brammer, Jan Heijndricxzoon & Maertge Jans</em>.](primary-sources-images/baptism_a_full.jpg)

Almost exactly a year after Reynier Jansz (Vermeer's father) was inscribed in the Guild of Saint Luke, the future artist was born to him and his wife, who were living on the Voldersgracht, twelve years after the birth of their first child, Gertruy. At this time, Digna Baltens, Vermeer's mother, was thirty-seven, and Reynier, his father, was forty-one years old. The new child was christened "Joannis" at the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church) on October 31, 1631, and his baptism was recorded in a vellum-bound church register, in a vellum-boundVellum is a fine-quality writing surface made from animal skin, historically used for manuscripts, documents, and the bindings of books. The term is derived from the Latin word "vitulinum" meaning "made from calf," leading to the English term "vellum," which originally referred to calf skin. However, over time, the term has come to encompass a broader range of animal skins, including those from sheep, goats, and other animals. church register (fig. 6 & 7).

John Montias's research reveals that Vermeer's baptismThe entry for Vermeer's birth in October 1632 and the entry for the famous Delft scientist and "father of microscopy" Antonie van Leeuwenhoek's on the same month (November 4) appear on the same page of the baptismal records book of the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church), He was registered as "Thonis Philipszoon." was somewhat of a break from the past. The ceremony was witnessed by a certain Pieter Brammer (a skipper), Jan Heijndricxzoon (a framemaker), and Maertge Jans. Neither Bramer nor Heijndricxzoon were likely family members, an unusual occurrence. The only certain family member was Maertge Jans, Reynier's sister. In the other baptisms of Reynier's siblings all were witnessed by close relatives.

An additional anomaly was the choice of Vermeer's first name, "Joannis," a Latinized form of "Jan" favored by Roman Catholics and upper-class Protestants. Reynier may have had ambitious plans for his first male child. However, on informal occasions, he was likely known as "Jan."

Vermeer, instead, was not an uncommon name. The name was sometimes spelled "'van der Meer" in documents by notaries and public officials, which means "from the lake," though neither Reynier nor his son preferred this variant. In 1667, when referred to as "Johannes van der Meer, artful painter" in a legal document, the painter himself signed as "'Johannes Vermeer." In 1670, during the division of Reynier and Digna's estate, lawyer Frans Boogert initially wrote their son's name as "Johannes van der Meer" but later crossed out "van der Meer."

Aside from his paintings, all traces of Vermeer have disappeared from the period between his baptism in October 1631 and his betrothal in April 1653. About all we can say with near certainty is that young Johannes grew up in his father's inns, first at The Flying Fox on the Voldersgracht, then at the Markt in Mechelen on Markt, with only one sibling, a sister twelve years older than himself. The rest is speculation.John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 98.

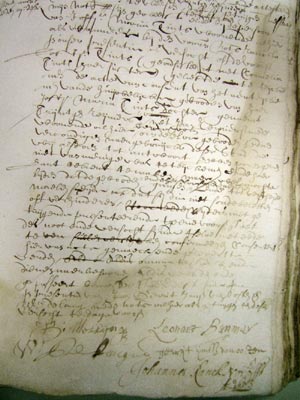

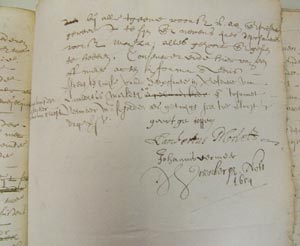

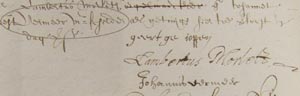

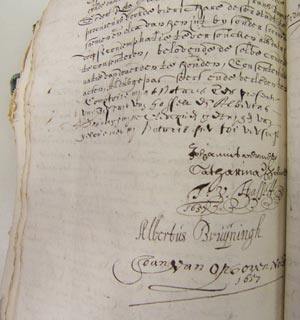

Leonaert Bramer's Appeal to Maria Thins: April 4, 1653

On the evening of April 4, 1653, at the request of Jan Reijniersz. [Vermeer] and Trijntgen Reijniers [Catharina Bolnes], the well-known Delft Catholic painter Leonaert Bramer (1596–1674) and the Protestant Captain Bartholomeus Melling, who served as Sergeant-major in Brazil and later as a flag-bearer for the States General, called on Maria Thins, Vermeer's future mother-in-law,Melling had been a captain and sergeant in Brazil, and was later an ensign in the service of the States General of the Dutch Republic. He probably belonged to the dominant Reformed religion so Montias suggests he may have represented the Protestant and Bramer the Catholic side in the confrontation with Maria Thins. Aside from Captain Melling, documents link Vermeer with two other individuals who were Captains. Shortly after his wedding, Vermeer and Gerrit ter Borch, served as witnesses at a deposition concerning Johan van den Bosch, Captain in the States General, stationed in Den Briel. On Jan. 10, 1654, Vermeer signed a document with Lambertus Morleth, Captain in the town of Clacken in the Land of Cleves called on Maria Thins, Vermeer's future mother-in-law.This document also suggests that Vermeer's network of friends included both Catholics and Protestants. They had with them a Delft lawyer named Johannes Ranck. This party had come to convince Maria that the young up-and-coming artist was a good match for her beloved daughter Catharina. Maria's sister was also present giving support and sympathy. Captain Melling may have represented the Protestant and Bramer the Catholic side in the confrontation with Maria Thins.The name of Melling, who frequented well-eslablisllcd Delft merchants, appears in a number of Delft documents.

"The visitors had come to ask Maria to sign a document permitting the marriage vows to be published. Maria replied that she would not sign such an act of consent. Despite this a subtle distinction —she would put up with the vows being published—she said several times that she wouldn't stand in the way of this (fig. 8 & 9). In other words, she didn't welcome the marriage but she wouldn't block it.

"The following morning the notary Ranck drew up a deed attesting to Maria Thins' sufferance of the vows being published, and this was witnessed not only by Bramer and Melling but by a man named Gerrit van Oosten and Delft lawyer Willem de Langue, De Langue was a serious picture collector, at whose house Vermeer might have seen works by, among others, Rembrandt, Roelandt Savery, and Bramer. both of whom had frequent dealings with the Bramer and Vermeer families."John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 216

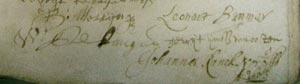

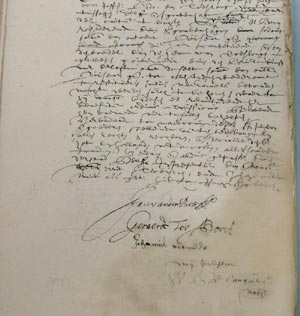

Record of Vermeer's Marriage to Catharina Bolnes: April 5, 1653.

On April 5, 1653, Vermeer's impending marriage to Catharina Bolnes was registered at Delft's city hall. Two weeks later, on Sunday, 20 April, the couple married in Schipluy (today Schipluiden), approximately an hour's walk from Delft. Catharina came from a relatively well-off Catholic family from Gouda, which was notable since Vermeer's family was Protestant. Before she married Vermeer, Catharina Bolnes lived with her mother, Maria Thins. The marriage is generally believed to signify the artist's conversion to Catholicism, marking a significant decision in the context of the religiously divided Dutch Republic of the seventeenth century." In terms of distance, the move from the inn of Vermeer's father on Markt to Oude Langendijk was just a little more than 100 meters for Vermeer. But his marriage had transported him into a very different milieu. Maria Thins' house was in the Papenhoek (Papists' Corner), where many of Delft's Catholics lived. At that time too, approximately a quarter of the population of Delft were Catholic. Partly under pressure from Reformed Church clergy, the governors of the city of Delft took a range of measures to suppress Catholicism in the city. However, they were also acutely aware that many Catholics made a significant contribution to the city's economic life. So Catholics were permitted to continue to practice their faith, provided this was invisible to the rest of society."David de Haan, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Babs van Eijk, and Ingrid van der Vlis, Vermeer's Delft (Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, Museum Prinsenhof Delft, 2023), 28.

Catharina's mother, Maria Thins, would be particularly influential in their lives, providing them with financial support and, eventually, housing them in her home. This home also served as Vermeer's studio, where he painted many of his most famous works.

Vermeer's own parents were married in 1615 in Amsterdam before Jacobus Taurinus (1576–1618), a famous Calvinist and Orthodox Reformed Church Minister. Although their marriage arrangement would seem to imply a commitment to the Reformed faith, neither of them was officially registered as a member of the faith which would have given them the right to participate in the sacrament of communion and an obligation to educate themselves in the doctrinal issues as well as a public confession of faith. Therefore, it appears likely that Vermeer's parents were part of a sizable group known as "supporters," individuals who, for various reasons, did not comply with the strict membership requirements or were averse to religious discipline.

The next morning the notary Ranck drew up a deed attesting to Maria Thins' sufferance of the vows being published (fig. 10 & 11), and this was witnessed not only by Bramer and Mellling but by a man named Gerrit van Oosten and the Delft lawyer Willem de Langue, who had frequent dealings with the Bramer and the Vermeer family. De Langue had a significant collection of paintings including works of Rembrandt and Bramer.

Maria likely sought to adhere to the counsel of local Catholic officials, who recommended that parents discourage their children from marrying outside the Catholic faith. This rare insight into Vermeer's private life reveals that the aspiring painter had notably gained the esteem of distinguished artists and prominent Delft citizens.

Vermeer's marriage is documented in a record dated April 5, 1653, with a marginal note specifying the small town of Schipluy—now Schipluiden—as the location of the union. Although the marriage banns were published in Delft, the young couple had requested a certificate allowing them to be joined in Schipluy where Catholicism remained well entrenched. Due to restrictions,In the 17th century, the Netherlands was a country undergoing significant religious, social, and political changes, which influenced the practice and recognition of Catholic marriages. The Union of Utrecht (1579) guaranteed freedom of conscience and private worship but did not extend to public practice of the Catholic faith. As a result, Catholic public worship was banned, and churches were taken over by Protestants. Catholic marriages, like other aspects of Catholic life, were often conducted in secret or in private chapels due to restrictions on public Catholic ceremonies. Although Catholic marriages were performed according to the rites of the Catholic Church, they were not legally recognized by the Protestant authorities. This lack of legal recognition could affect issues of inheritance, legitimacy of children, and other legal matters. Catholic weddings were not held publicly, often taking place in barns or similarly discreet locations. When Vermeer married Catharina Bolnes, in essence, he became de facto part of a Roman Catholic family and a Roman Catholic neighborhood with its advantages and disadvantages.

![5 en 20 April, 1653. Den 5en Apprill 1653: Johannes Ryniersz. Vermeer J[ong] M[an] opt Marctvelt, Catharina Bolenes J[onge] D[ochter] mede aldaar. [margin note left-side:] Attestatie gegeven in Schipluijden 20 April, 1653 5 and 20 April, 1653.](primary-sources-images/marraige-detail.jpg)

Following his marriage, Vermeer appeared to distance himself from his own family, with none of his children receiving names from his side as was customary. Instead, the name of Maria was given to the first child in honor of Maria Thins and the Virgin Mary. Another daughter, Elizabeth, was perhaps named after Catharina's aunt who had become a nun in Flanders. The name Ignatius was undoubtedly chosen to honor Saint Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order. Vermeer's first son, Johannes, eventually pursued a vocation as a priest.

Despite Vermeer's family being of lower social status than the Bolneses—a fact Maria Thins likely knew, including the involvement of Vermeer's grandfather in a counterfeit ring, narrowly escaping beheading—the young painter managed to alleviate her considerable anxieties. Maria's own marriage had been full of domestic violence and ended with a divorce. Perhaps the close ties that Maria Thins' family had with the successful Delft painter Leonaert Bramer guaranteed the artist's prospects.

In any case, it would appear that Maria comprehended Vermeer's artistic calling. Throughout the couple's married life, she consistently enhanced her daughter's financial position and supported the young painter's children, and his activity as an artist.

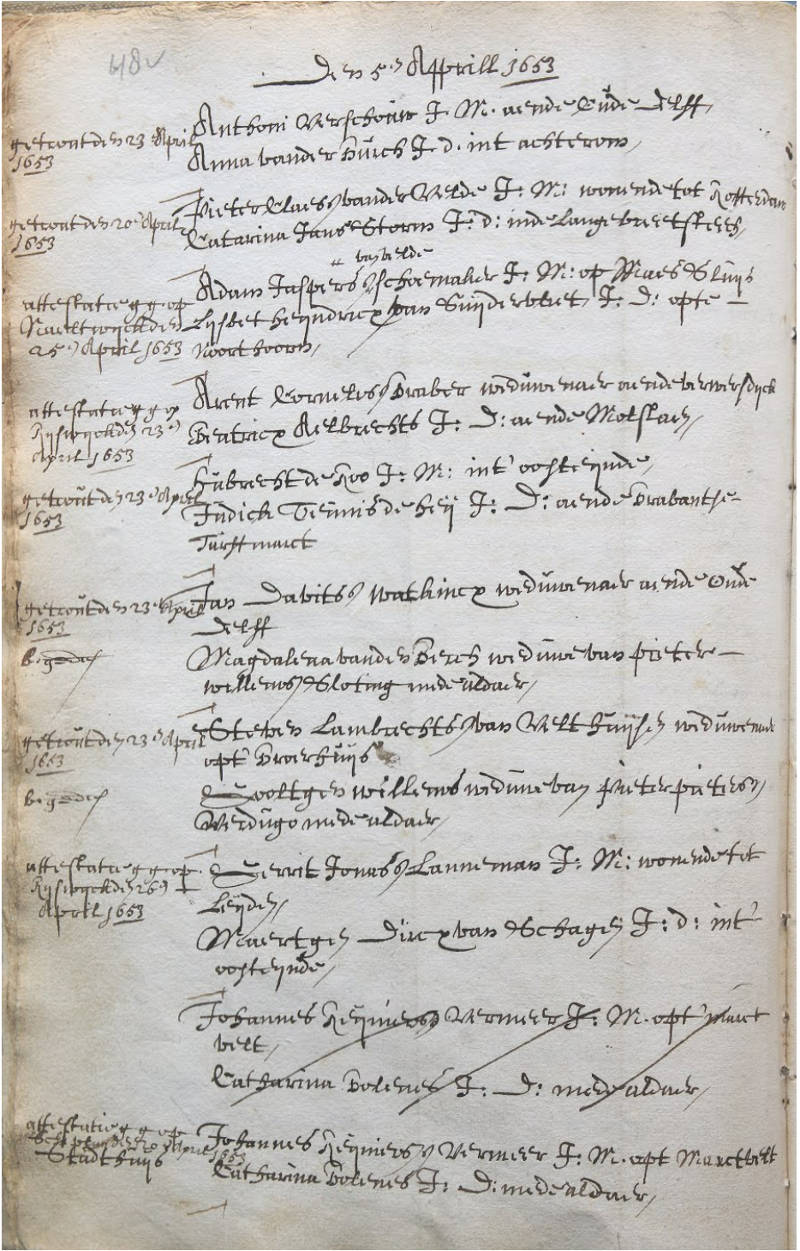

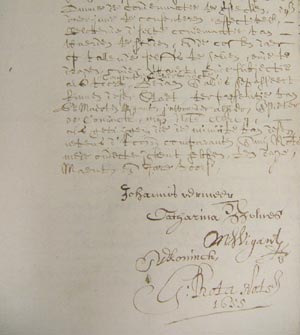

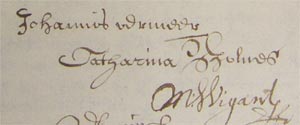

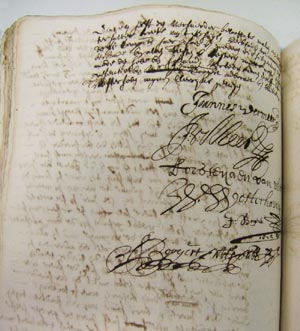

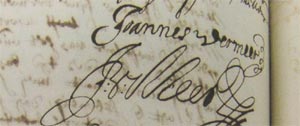

Vermeer and Gerrit ter Borch Witness an Act of Surety: April 22, 1653.

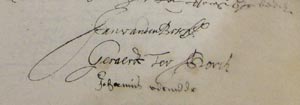

On April 22, 1653, Johann van den Bosch, a captain in the service of the States General stationed in Den Briel, offered surety to enable Juffr. Dido van Treslong to collect 1,000 guilders owed to her from the estate of the late Lord of Treslong, former Governor of Den Briel (fig. 12 & 13). Van den Bosch guaranteed restitution of the sum if necessary.

"Gerrit ter Borch (1617–1681), painter of elegant society pieces at the time, and the just-married Vermeer, were also there. Were Vermeer and Ter Borch witnesses who happened to be present when the document was drafted, or was either man connected with Captain van den Bosch or Dido van Treslong? No link can be documented, but it would not be surprising to find that Vermeer knew Van den Bosch via Captain Bres, who later settled in Den Briel, or via his uncle, Lieutenant Reynier Balthens."John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 102. No other connections between the two artists can be established. In fact, when the American economist and Vermeer biographer John Michael Montias discovered this document, it was not even known that Ter Borch had ever set foot in Delft.

The elder painter signed "Geraerdt Ter Borch," the younger "Johannis Vermeer." The notary referred to Ter Borch as "Monsieur" a sign of his respect for the thirty-six-year-old artist who was then at the height of his powers. Vermeer, instead had not yet an accepted master of the Delft Guild of Saint Luke. As Vermeer had been married just two days earlier to Catharina Bolnes, it is possible that the elder painter had come expressly for the event.

"Ter Borch signed his name below Van den Bosch's in a large and firm hand. Vermeer's signature, just below Ter Borch's, is smaller and more timid, as befitted a younger confrere who was not yet a master in the guild (fig. 13). The two artists may have met fortuitously that day at the notary's, but it seems much more likely that they were previously acquainted."John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 102.

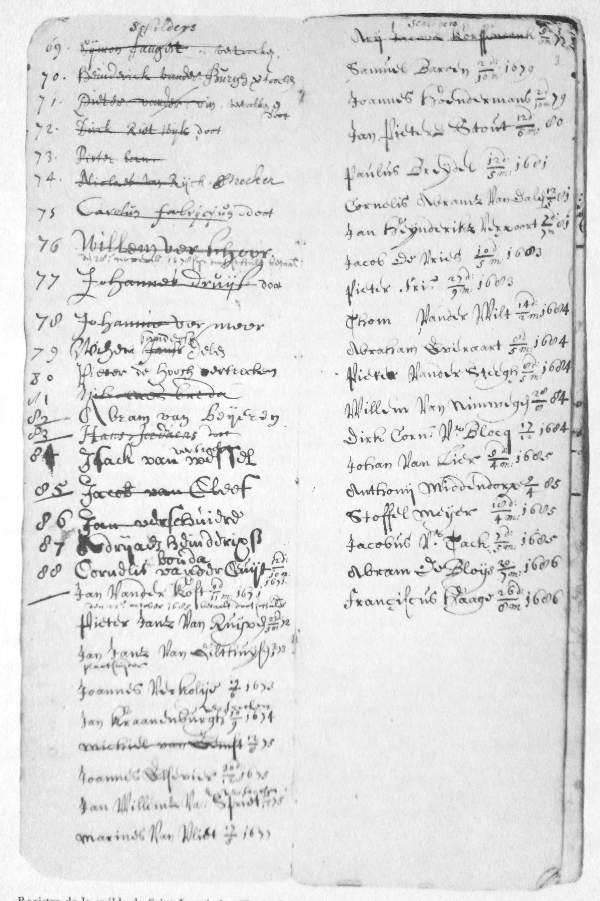

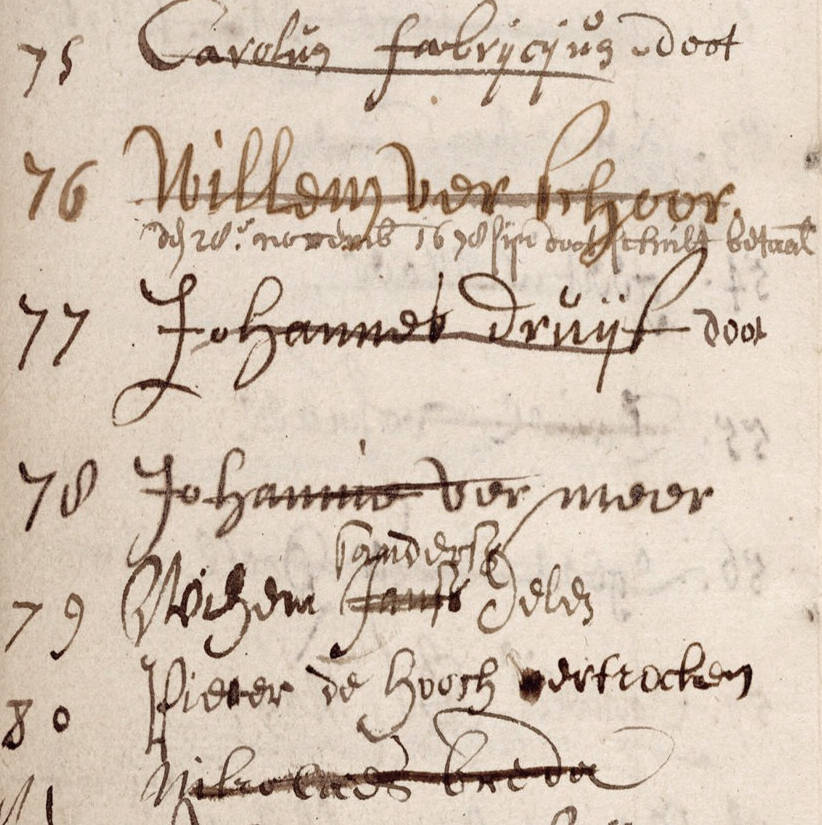

Guild Book of Delft Master Painters, Engravers, Sculptors, Potters, etc. in the Seventeenth Century. Part 1: 1613–1649.

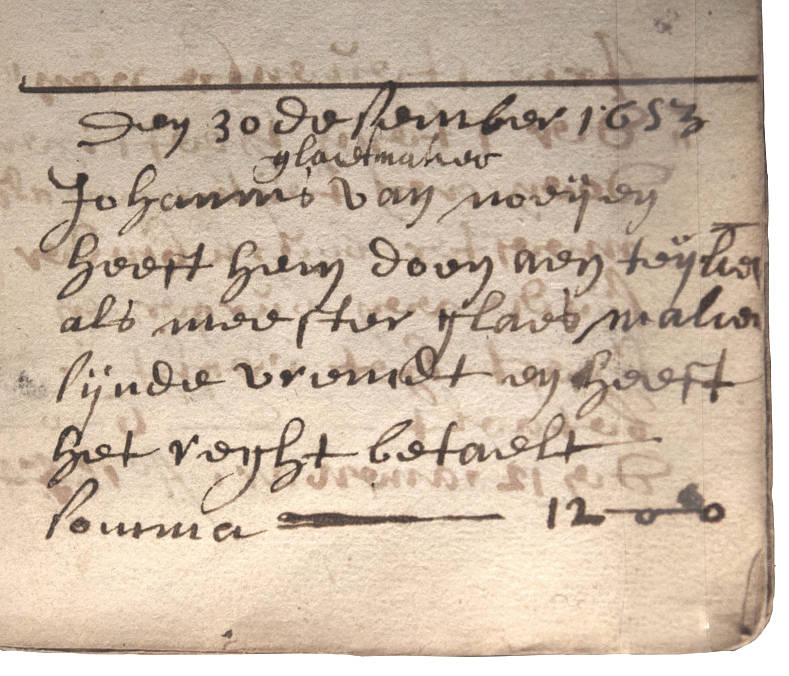

On December 29, 1653, at the age of 21, Vermeer joined the Delft Guild of St. Luke (fig. 14, 15 & 16), initially paying just one guilder and ten stuivers out of the six-guilder incomstgelt (entrance fee), settling the balance in 1656. Historians note that, contrary to the expected half-rate of three guilders for the son of a guild member who might also serve as an apprentice to a Delft guild painter for at least two years, he was charged six guilders. The young artist may not have received the discounted rate because his father, Reynier, although a longstanding guild member, was an constvercoper (art dealer), not a professional painte. Alternatively, if Reynier had recently passed away at that time, this could have affected the fee. Another possibility is that the higher fee of six guilders was applied because Johannes was seen as having studied outside of town. This suggests Vermeer could demonstrate several years of apprenticeship under a master, though the specific painter or painters from whom Vermeer learned his trade remain unknown. Well-known painters Pieter de Hooch (1629–in/after 1679) and Carel Fabritius (1622–1654), and the painter Leonaert Bramer, were also members of the guild as master painters. Fabritius, who joined the guild in 1652, was not a member for long, however.

Guild membership enabled Vermeer to sell his paintings and mentor apprentices. Initially without a meeting place, the guild likely convened in members' homes or local inns. In 1661, they acquired the former chapel at the Oude Mannenhuis alms-houses. By 1667, after significant renovations, the Guild's premises were permanently established at Voldersgracht number 21, where Vermeer would later serve as headman. After it had undergone significant renovations it reopend in great cerimony in 1667. The structure's rear faced direcly Mechelen , whereVermeer's family had resided, presnting a view of its facade over the canal. In addition to painters, the Guild included glassmakers, potters, printers, tapestry makers, printmakers, and sculptors among its members. Conversely, artisans like silversmiths had their own separate guild. The administration of St. Luke's Guild comprised six headmen, with three new headmen elected annually.

The dissolution of the guilds during Napoleon I's reign led to the destruction of all registry documents. Nonetheless, a vital record has survived: a small booklet preserved at the Royal Library in The Hague. However, a singular vital record has survived this purge: a diminutive booklet, now safeguarded within the Royal Library in The Hague.

The Royal Library booklet is of particular historical significance as it includes entries in Vermeer's own handwriting. Vermeer's tenure as headman across four one-year terms—1662, 1663, 1670, and 1671—during which he personally registered new members, underscores his leadership and active involvement in the guild.Kaldenbach, Kees. "The Delft St Luke Guild: How it was Run." Johannes Vermeer Info. Accessed February 15, 2024.

Vermeer is Mentioned as a "Master Painter": January 10, 1654.

January 10, 1654, Vermeer is mentioned for the first time as Meester-schilder (Master painter) indicating he had by this time improved his professional and social status (fig. 17 & 18).Johan Michael Montias, who has examined the guild's records, reckons the number of master painters in Delft to have been forty-seven in 1613, fifty-eight in 1640 (the peak for painters), fifty-one in 1660, and thirty-one in 1680. Printers, not painters, generally formed the wealthiest profession. But as the century passed the faience-makers were those who showed the greatest increase in numbers: in 1650 there were thirteen of them, when there were fifty-two painters; in 1680 there were fifty-seven faience-makers and, as noted, thirty-one painters. New potteries were being set up, many in former breweries. Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2002), 89. Another witness was a certain Captain Morleth from the Duchy of Cleves. It raises the question of whether it was mere coincidence that Vermeer's name appeared alongside those of military officers in four consecutive legal documents: Sergeant-Major Melling during his engagement; Captain van der Bosch when he jointly witnessed with Ter Borch; his uncle, Lieutenant Baltens, the very next day; and Captain Morleth only a few months afterward.

DECLARATION CONCERNING JOHAN VAN SANTEN WITH THE SIGNATURES OF JOHANNES VERMEER AND HIS WIFE: CATHARINA BOLNES: December 14, 1655.

This document, discovered by Abraham Bredius a century ago, was dated December 14, 1655 (fig. 19 & 20). "On this day, Sr. Johannes Reijnijersz. Vermeer, master painter," and his wife "Juffr. Catharina Bolnes," appeared before Notary Rota to guarantee a debt of 250 guilders, which the artist's father had contracted in 1648 from a sea captain named Johan van Santen.ohan van Santen, the son of Cornelis van Santen, a prominent member of the Reformed Community and a regent of the Delft Orphanage, and the brother of the military officer and playwright Gerrit van Santen, later became a captain of the Delft militia commanding the orange-pennant shooters ("orange vendel schutters"). He was forty-four years old when he guaranteed the loan. In 1655, three years after the death of Reynier Jansz., Johannes Vermeer and his wife Catharine Bolnes discharged Captain Johan van Santen of his guarantee and undertook to repay the loan themselves. If Reynier Jansz. had access, via Johan van Santen, to the milieu of Johan's brother Gerrit, this might have been very valuable to him in his art-dealing activity. The playwright, who died in 1656, was friendly to some of the most eminent collectors and art lovers of Delft. In the 1610s, he dedicated one of his plays to Boudewijn de Man, who owned what was perhaps the finest collection of paintings in Delft, and another to Maria van Bleiswijck, who belonged to one of the two or three most eminent "regenten" families in Delft and appears to have been a patroness of the arts. It is also possible that Johan van Santen introduced Vermeer into this artistic circle. John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 77. Nine years later, Digna Baltens and Vermeer, who had acquired the obligation after Reynier's death, were still paying the interest on this debt. The "Sr." (signior or seigneur) preceding Vermeer's name signifies the artist's rise in social status. It will be recalled that Vermeer's father was never addressed in such a manner in any of the numerous documents pertaining to him.John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 134.

Vermeer and His Wife Catharina Bolnes Contract a Loan of 200 Guilders from Pieter van Ruijven: November 30, 1657.

This document provides the first definitive evidence of contact between Vermeer and his future patron, Pieter van Ruijven. Van Ruijven lent Vermeer and Catharina 200 guilders at an extremely low interest rate (fig. 20 & 21) . According to John Montias, this may have served as an advance for the purchase of one or more paintings.

Johannes Vermeer Leases Mechelen: January 4, 1672.

Like his father, Johannes Vermeer was also an art dealer. From 1672, he also derived income from leasing Mechelen, which he had inherited

following his mother’s death (in 1670). On January 4, 1672, he leased it to Johan van der Meer, an apothecary, for a period of six years (fig. 22 & 23). This lease began on May 1 of the current year, with an annual rent of 180 guilders. Vermeer signed this formal legal document, confirming the agreement.

The document highlights Vermeer's shift towards a Latin writing style, marked by his adoption of the Latinized first name "Joannes." This change likely signifies Vermeer's effort to align with the cultural trends of his era.

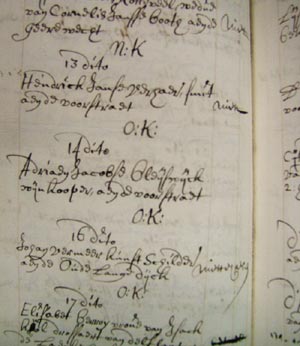

Vermeer's Family Leaves Nothing to the Kamar van Charitate: December 16, 1657.

"On December 16, 1675, the day Vermeer's coffin was placed in the family grave, an inscription was made under his name in the book recording death notations to Delft's Kamer van Charitate (Chamber of Charity) (fig. 24 & 25). The inscription in Dutch read: niet te halen, which may be translated as "nothing to be got." The reference was to the box that was normally sent to the house of the deceased. In this box, his family or heirs were supposed to deposit his "best outer garment" or a suitable donation for the poor.

About half of the required income of the Kamer van Charitate came from donations, the rest from land ownership and various levies that have to be paid by the citizens of Delft. Thus, the Kamer received "additional cents" on the city taxes on the sale of real estate, wine, and peat. A very creative levy was that of the so-called "best outer garment." The most expensive clothing item from the estate of every deceased resident had to be handed over. From time to time, sales took place at the auction house, after which the proceeds flowed into the Kamer's coffers. Relatives were free, however, not to hand in the garment itself but to pay an amount determined by the appraisal of the auction house master, up to a maximum of one hundred guilders." "Bij Vermeer is niets te halen," Erfgoed Delft Stadsarchief. March 22, 2021. Accessed February 24, 2024. When Vermeer's mother and sister Gertruy died in 1670, the heirs (Vermeer and Antony van der Wiel) donated 6 guilders and 6 stuivers to the Commissioners for each of the deceased, a modest enough contribution but about average for a lower-middle-class family in Delft.John Michael Montias, "Chronicle of a Delft Family," in Vermeer, edited by Albert Blankert, Gilles Aillaud, and John Michael Montias, (Woodstock and New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2007).

Yet, why was no donation made after the artist's death? Was it because the widow, burdened with so many children, was too poor? Or because the family was Catholic and did not wish to contribute to an organization run by Calvinists? Montias suggests that a contribution to the Camer was made after the death of Maria Thins, which would seem to rule out the religious explanation. The failure to donate is most probably rooted in Catharina's insolvency, declared a few months later."John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 337

The decision is curious, considering that the posthumous inventory of Vermeer's estate, prepared by his widow Catharina, included valuable items such as a yellow satin cloak with white fur and a black Turkish cloak. Despite the potential to auction these items for charity, the Kamer van Charitateconcluded that it was unable to collect any charitable contributions from his estate. This decision prompts questions regarding their judgment.

Established in 1597 by Delft's city governors, the Kamer van Charitate aimed to support the poor, operating from Schoolstraat behind the Prinsenhof. It engaged in charitable activities such as distributing bread, turf, occasionally clothing, or money. During the seventeenth century, financial hardships or the loss of a family's breadwinner often plunged 11 to 15 percent of Delft households into poverty, necessitating reliance on charity. This was particularly true for women left behind by husbands serving in the military or with the East India Company. In contrast, Vermeer benefited from his mother-in-law's financial support, sparing him and his family from the struggles faced by many others in Delft.

Vermeer's Grave

Vermeer was forty 1672. Several children more were born to him and Catharina in these years: in 1672 a son they called Ignatius; an infant—perhaps stillborn—who died in June 1673 and was buried in the family grave in the Oude Kerk;December 15, 1675. From the register of the Oude Kerk: "Person en die binnen deser Stad Deiff overleden ende in de Oude Kerck als oock daer buijten begraven sijn tsedert den 19 Julij 1671": "Jan Vermeer kunstschilder aen de Oude Langedijk in de kerk. [In the margin:] 8 Me:J:kin.d" ("Jan Vermeer painter on the Oude Langedijk, in the church. [In the margin:] 8 children under age"). and a child whose name we do not know who came into the world in 1674 and lived only four years. All were burried, like Vermeer as well was to be, in a grave in the Oude Kerk that his mother-in-law, Maria Thins, had bought on December 10, 1661.

"Vermeer's own burial involved a rearrangement of the family grave. The infant who had been buried two and a half years earlier was taken out momentarily while Vermeer was lowered into the grave, and then the tiny remains of the child were put on top of its father's coffin. Maria Thins was at home on the Oude Langendijck when she received the last sacrament of Extreme Unction on December 23, 1680. Her neighbour the Jesuit priest Philippus de Pauw anointed her with holy oil and prayed at her bedside. Four days later she was buried in the Oude Kerk. Fourteen pallbearers made a prosperous show of mourning, and a generous donation of twenty-five guilders and four stuivers was given to the Chamber of Charity. The family grave she had bought years before was now designated as 'full.' It was perhaps just as well Vermeer had gone first because his greatest day-by-day benefactor was no more."Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2002), 204-210.

Montias entry 358 John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989).

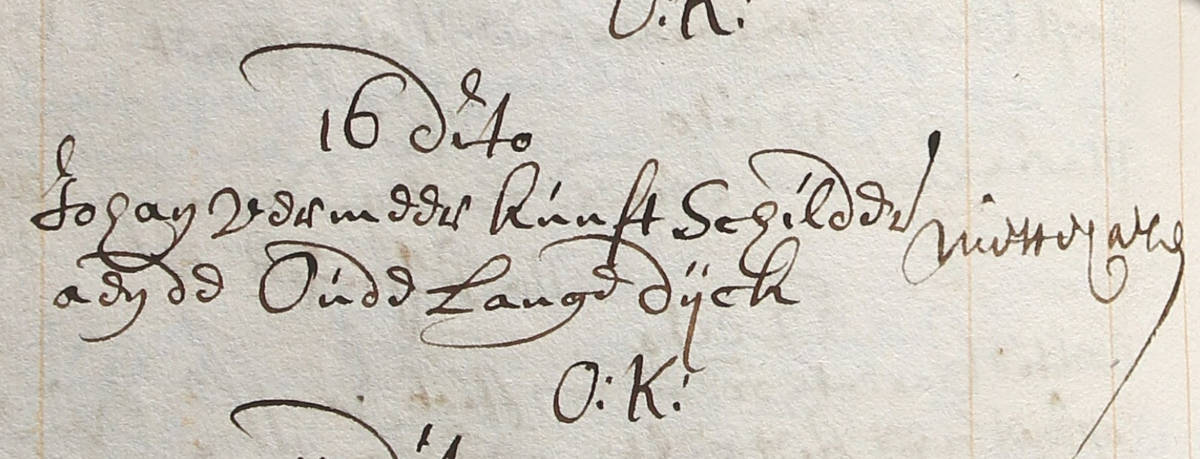

16 December, 1975. 16 dito (second from below):

Johan Vermeer kunst Schilder aen de Oude Langendijck

niet te haelen [= note right-side]

O:K: [Oude Kerk]

Vermeer's Funeral Casket is Held by 14 Pallbearers: December 16, 1675.

The former archivist, The former archivist, Bas van der Wulp, at Erfgoed Delft, the city's cultural heritage department, has recently discovered a burial record of the Oude Kerk that reveals previously unknown details about the funeral of Vermeer on December 16, 1675 (fig. 26). Notably, Vermeer's coffin was carried by fourteen bearers, and the church bell was rung, indicating a lavish ceremony.The discovery of the funeral note can be considered remarkable, according to the Prinsenhof Museum, in light of the extensive research on Vermeer done by so many scholars for over a hundred years.Van der Wulp himself, who has worked for the archive for 45 years, had never made such a discovery previously.

Similarly, grand funerals were accorded to Vermeer’s brother-in-law, Willem Bolnes, and his mother-in-law, Maria Thins. Maria Thins' funeral even included two bell tolls instead of Willem and Vermeer's one. Given these observations, it is speculated that Maria Thins may have been the benefactor for Vermeer’s funeral expenses. Van der Wulp posits that Thins might have opted to bear the funeral costs, possibly without full knowledge of Vermeer’s dire financial situation, which had worsened markedly after the Rampjaar (Disastrous Year) of 1672, rendering him penniless.

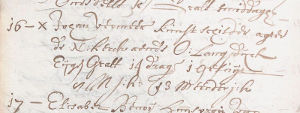

Monconys, Balthasar de. Journal des voyages de Monsieur de Monconys, Conseiller du Roy en ses Conseils d'Estat and Privé, and Lieutenant Criminel au Siège Presidial de Lyon, 2 vols., Lyon, 1665–1666.

Balthasar de Monconys (1611–1665) was a French traveller, diplomat, physicist, and magistrate known for his extensive travels and the detailed journal he kept, which was published posthumously as Journal des voyages de Monsieur de Moncony…(fig. 27)

Monconys's journal documents his travels across Europe, the Middle East, and potentially other regions. His travels, conducted during the mid-seventeenth century, occurred in an era notable for significant discoveries and the exchange of knowledge globally. Monconys had a keen interest in science, technology, and art, and his observations reflect a wide-ranging curiosity about the cultures and innovations he encountered. His friends and family, including his son, Gaspard de Monconys de Liergues, sought to impress scholars with the notion of a man of unlimited curiosity.Blaise Ducos, "The 'Tour of Holland'," in Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry, edited by Adriaan Waiboer and Eddy Schavemaker (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 107. The journal contains detailed observations on natural phenomena, technological inventions, and encounters with eminent scientists, artists, and intellectuals. He often went out of his way to visit scholars, laboratories, and libraries, documenting his findings with a meticulous eye. He was not, however, appreciative of Vermeer's painting (see below), having encountered only one example, (The Milkmaid).

Published posthumously, The Journal des voyages was swiftly acknowledged for its contributions to broadening understanding of the world beyond Europe. His detailed descriptions and analytical approach to what he observed make his journal a significant document for historians studying the period's scientific, cultural, and intellectual history.

In any case, "conditions for travelers in Holland in the latter half of the century, be they aristocrats, people in royal retinues, or well-heeled tourists, were good, and it was easy for artists and liefhebbers (art lovers) to move around the country and to keep abreast of everyone else's work. Monconys's taste for gemstones and his partiality for theoretical science and its development as well as for art are typical of the time. He would not have understood if asked to distinguish between alchemy and chemistry."Blaise Ducos, "The 'Tour of Holland'," in Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry, edited by Adriaan Waiboer and Eddy Schavemaker (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 107.

Monconys, a man with a trained taste, passionately loved the arts and sciences. Before visiting Delft three times in 1669, where Vermeer worked, he had just come from England where he had met, among others, Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), the political philosopher; Mr. Reeves, known for constructing telescopes and an acquaintance of the English diarist Samuel Pepys; and Henry Oldenburg (c. 1618–1677), secretary of the Royal Society. Monconys had also attended the society's proceedings with Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687), Dutch diplomat, poet, and scholar (he was also secretary to two Princes of Orange: Frederick Henry and William II, and the father of the scientist Christiaan Huygens).

Renowned art historian Ben Broos, specializing in seventeenth-century Dutch art, states, "Monconys visited Delft during the summer of 1663. He came initially as a tourist,On Monconys's second vist to Delft on August, Monconys went again to Delft by barge - the fare from The Hague was '2 sols par homme'—and visited the Town Hall. evidently unaware of Vermeer's presence. A few weeks later, he went to pay his respects in The Hague to Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687), an important diplomat, art connoisseur, and theorist of Dutch culture. Monconys admired his art collection and described it in detail in his personal diary."Ben Broos, "Un celebre Peijntre nommè Verme(e)r," in Johannes Vermeer, eds. Ben Broos and Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. (Zwolle: Waanders, 1995).

However, one can only imagine how amazed Huygens must have been to hear that the Frenchman had been in Delft, without visiting Vermeer. Given Huygens' familiarity with leading artists of the time [he personally brokered the sale of two important works by the young Rembrandt van Rijn. Given Huygens' connections, it's plausible he recommended Monconys meet with Vermeer, given the Frenchman's interest for fine art. Subsequently, Monconys visited Vermeer at his home and documented the encounter in his diary, which was published in 1665, the year of his death, noting, (fig. 28):

[…] À Delphes [i.e. Delft] je vis le Peintre Vermer [sic] qui n'avoit point de ses ouvrages : mais nous en vismes un chez un Boulanger qu'on avoit payé six cens livres, quoyqu'il eust qu'une figure, que j'aurois cru trop payer de six pistoles.

(In Delft I saw the painter Verme(e)r who did not have any of his works: but we did see one at a baker's, for which six hundred livres had been paid, although it contained but a single figure, for which six pistoles would have been too high a price.)

![Journal des voyages de Monsieur de Monconys, Conseiller du Roy en ses Conseils d'Estat & Privé,

& Lieutenant Criminel au Siège Presidial de Lyon. Balthasar de Monconys, 2 vols., Lyon, 1665–1666. (vol. 1 [1665], page 148 [top]–149 [bottom])](primary-sources-images/monconys-detail.jpg)

du Roy en ses Conseils d'Estat & Privé,

& Lieutenant Criminel au Siège Presidial de Lyon

Balthasar de Monconys

2 vols., Lyon, 1665–1666. (vol. 1 [1665], page 148 [top]–149 [bottom])

No one knows precisely why Monconys saw no paintings at Vermeer's house. Some scholars believe that Vermeer, having produced relatively few works, simply had none at the time to show him because they had been bought by his clients and patrons (Pieter van Ruijven and his wife Maria de Knuijt) as soon as they were finished.

Although Monconys only briefly touched upon his perception of Vermeer's work, and deprecated its worth, it is clear from his account that there existed select connoisseurs in prominent circles, Konst-vroede Liefhebbers (experienced art lovers), who were aware of Vermeer's artistic skills. Unfortunately, Monconys made no mention of the style or quality of Vermeer's painting—it appears he judged them exclusively on the basis of the number of hours required to do the work.Ben Broos, "Un celebre Peijntre nommè Verme(e)r," in Johannes Vermeer, eds. Ben Broos and Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. (Zwolle: Waanders, 1995), 48.

Presumably, at that time, a Vermeer painting evidently had the same market value as an authentic work by Gerrit Dou (1613–1675), whom Charles II of England had invited to become his court painter in 1660.

"The brief and lapidary nature of Monconys's diary entry on Vermeer was not influenced by religious differences. Both men were Roman Catholics. Vermeer, who was initially from a Protestant family, converted to Catholicism before his marriage to Catharina Bolnes in 1653. Monconys was baptized in Sainte-Croix and educated by Jesuits in Lyon. Their meeting occurred in Delft's Catholic quarter, the Paepenhoek, and Monconys's interactions with other Dutch artists in various cities suggest that religion did not hinder his artistic explorations. Instead, his motivations were driven by curiosity, a desire to acquire curios, and an interest in people.For De Monconys's visit to Delft see also E. Neurdenburg, "Nog enige opmerkingen over Johannes Vermeer van Delft," in Oud-Holland 66, 1951, 33-44.

"It has also been speculated that social hierarchy might have influenced Monconys' brief and somewhat disappointing assessment of Vermeer and his work. Monconys came from an old Burgundian aristocratic family dating back to the thirteenth century, while Vermeer was an art dealer and painter who gained social standing through marriage to the daughter of a wealthy woman, placing him in a different social stratum. Despite what biographers might suggest, Monconys appeared to take pleasure in associating with high society, which could have colored his view of Vermeer."Blaise Ducon, "The Tour of Holland," in Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry, edited by Adriaan Waiboer and Eddy Schavemaker (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 109.

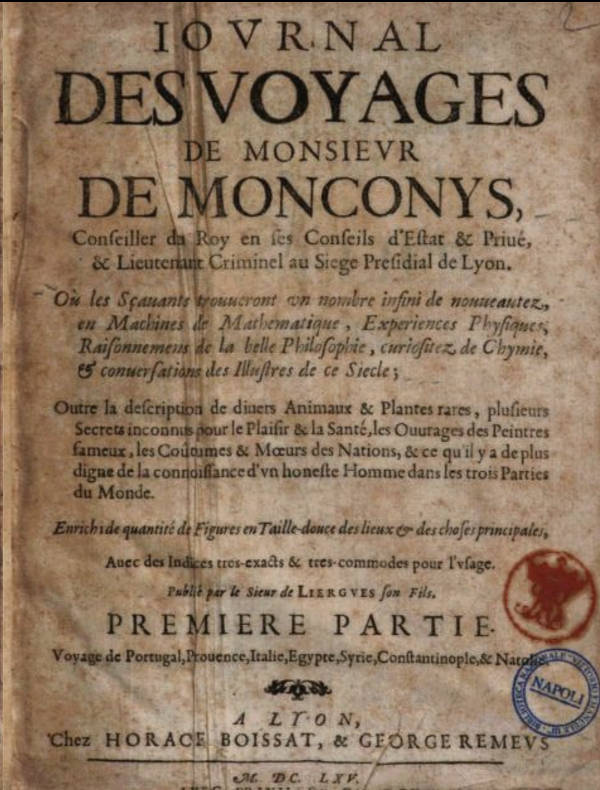

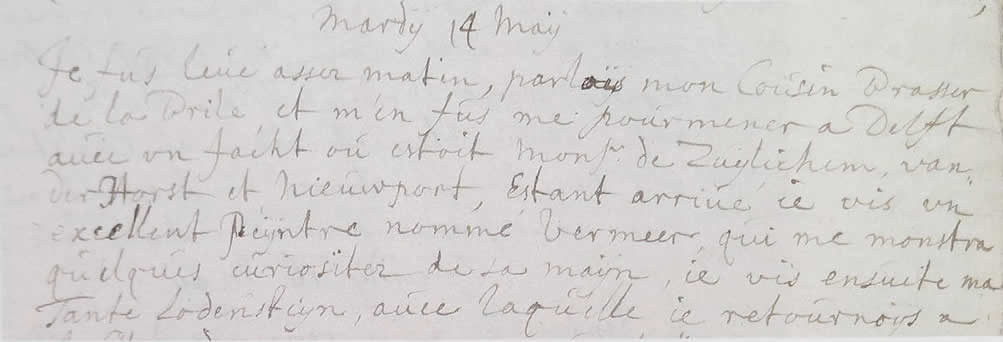

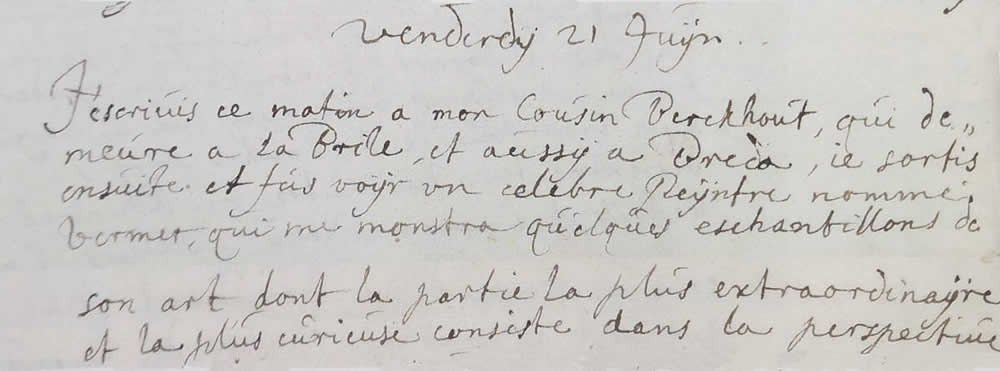

Van Berkhout, Pieter Teding van. Fragments of the diary of Pieter Teding van Berkhout, Koninklijke Bibliorheek, The Hague. May 14, 1669.

Apart from the account of the Frenchman Monconys, the only known written eyewitness account of Vermeer's paintings was authored by Pieter Teding van Berkhout (1643–1713) (fig. 29), a young scion of a landed gentry family and son of a governor in The Hague.Van Berkhout owned an art collection, some of which was bequeathed to him by an aunt. His collection was diverse, encompassing not only artwork but also scientific tools such as two cameras obscura and microscopes. In 1674, he moved to Delft and settled in a notable building on Oude Delft, subsequently joining the city's administrative upper echelon. Van Berkhout had gathered and inherited a major fine art collection as well which included 68 paintings: 7 history subjects, 17 landscapes, 10 architectural views, 4 marinescapes, 12 genre paintings, and 4 Still lifes and 14 portraits. Thanks to shrewd investments in property and bonds, he had become a very wealthy man. Van Berkhout had an art collection, part of which he had inherited from an aunt. His interests were broad; his estate included two cameras obscuras, microscopes, and other scientific instruments. In 1674, he relocated to Delft where he moved into a prestigious building on Oude Delft and became a member of the city's administrative elite.David de Haan, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Babs van Eijk, and Ingrid van der Vlis, Vermeer's Delft (Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, Museum Prinsenhof Delft, 2023), 69.

The young Van Berkhout arrived at Delft from The Hague by boat accompanied by Constantijn Huygens, perhaps, in order to facilitate Van Berkhout's introduction. No other reason is given for Huygens's presence in Delft. However, considering that Huygens was the secretary to a Prince of Orange and acquainted with Rubens and Rembrandt, he may have also been there to see Vermeer. Van Berkhout did not provide clarity on this matter but writes in his diary, in French: "having arrived, I saw an excellent painter named Vermeer, who showed me some curiosities by his hand." A week later, apparently impressed by what he saw, in his diary entry of May 14, 1669, he wrote (fig. 30 & 31),

Le 14 mat 1669 : je fus leve assez matin, parlois a mon cousin Brasser de la Brile, et men fus promene a Delft avec unjacht ou estoit Monsieur de Zuylechem van der Horts et [Monsieur de] Nieuivpoort. Lstant arrive ie vis un excellent peijntre nomme Vermeer, qui me montra quelques curiosites de sa main.

(14 May 1669: I got up quite early, spoke with my cousin Brasser de la Brile, and went to visit Delft in a yacht with Mr. Zuylechem van der Horts and [Mr.] Nieuwpoort. When I arrived I saw an excellent painter named Vermeer, who showed me some curiosities he had executed himself.)

Casper Netscher

Oil on copper, 13.3 x 11.1 cm.

Teding van Berkhout Foundation, Amersfoort

That Van Berkhout twice visited Vermeer and twice praised him somewhat contradicts romantic notions about Vermeer's social isolation.Ben Broos, "Un celebre Peijntre nommé Verme[er]" in exh. cat. Johannes Vermeer. Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Ben Broos, London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995, 50.

The journey would have taken an hour-and-a-half to two hours by trekschuit (towbarge) The trekschuit was a relatively swift, comfortable, and reliable mode of transportation which had significant social and political consequences. The trekschuit system greatly enhanced mobility within the Dutch Republic, facilitating easier and more frequent travel for both people and goods. This improved connectivity played a crucial role in the economic development of the region, as it allowed for the quicker and more efficient movement of goods, contributing to the flourishing of trade and commerce. Socially, the trekschuit made it possible for people from different towns and regions to interact more regularly, leading to a greater exchange of ideas and cultural practices. He was accompanied by Monsr. de Zuylichem (Constantijn Huygens) and his friends—a member of parliament Ewout van der Horst (c. 1631–before 1672) and ambassador Willem Nieupoort (1607–1678).Ben Broos, "Un celebre Peijntre nommé Verme[er]" in exh. cat. Johannes Vermeer. Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Ben Broos, London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995, 50. Huygens was an artistic authority in his own day, maintaining contacts with the famous Flemish painters Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641). He recorded in his diary some remarkably insightful comments about the art of, among others, Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669).In December 1669, he visited Caspar Netscher's studio in the court city and "the famous Dou" in Leiden. Earlier in April of the same year, the diarist had visited the Dordrecht studio of Cornelis Bisschop, praised for his excellent perspective in painting. However, as far as we know, Huygens did not visit the Vermeer 's studio. Nonetheless, "The connection between Van Berkhout and Huygens in this instance bolsters the observation…concerning networks of like-minded elites during the seventeenth century. Both men were enormously affluent art lovers and collectors. Both had voracious intellects, owned large personal libraries, had travelled abroad and were fluent in French, the language of high society in the Dutch Republic at this time. They not only shared similar cultural pursuits but also many relatives, friends, and acquaintances. On several occasions,Van Berkhout, his wife, and his sister Jacomina (1645–1711) visited Huygens' country estate, Hofwijck, outside The Hague, as courtesy calls of this sort served important social functions for the well-to-do. In time, relations between these two prominent families were cemented with the marriage in 1674 of Huygens' son Lodewijk (1631–1699) to Jacomina."Wayne Franits, Vermeer (Art & Ideas) (London: Phaidon Press, 2015), 205

Pieter Teding van Berkhout

Paper

Kononlijke Bibliotheek, The Hague

People of Van Berkhout's social standing had a deep appreciation for the visual arts as a fundamental part of a gentleman's education. To cater to these enthusiasts, guides such as Pierre Le Brun's Essays on the Wonders of Painting (1635)Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Lebrun, Essai sur les moyens d'encourager la peinture, la sculpture, l'architecture et la gravure, Paris, 1794-1795. were published, informing the reader that in order "to discourse on this noble profession, you must have frequented the studio and disputed with the masters, have seen the magic effects of the pencil [brush], and the unerring judgement with which the details are worked out." "Moreover, the specific language Van Berkhout employed to describe Vermeer's paintings contained essential vocabulary for connoisseurs in the know who excelled at the all- important skill of conducting conversations about art. The diary and Teding van Berkhout's very visits point to the rarefied world of patronage and connoisseurial networks in which Vermeer trafficked."Franits, Wayne. Review of VERMEER, by Pieter Roelofs and Gregor J. M. Weber, eds. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, February 10–June 4, 2023. In Renaissance Studies 37, no. 4 (2023). Rijksmuseum/Hannibal Books, 2023.

Pieter Teding van Berkhout

Paper

Kononlijke Bibliotheek, The Hague

Van Berkhout was also a close acquaintance of Dirck van Bleyswijck, whose Beschryving der Stadt Delft (Description of the City of Delft) had first appeared in 1667. This work contains a now-famous poem by Arnold Bon. In it, Bon laments the untimely death of Carel Fabritius (1622–1654), Rembrandt's most talented pupil, in the explosion of the Delft powder magazine (1654). Despite the loss of Fabritius, Bon praised rising star Vermeer, who "luckily arose" from the fire.

Van Berkhout became a member of Delft Council of FortyThe Delft Council of Forty, or Vroedschap van Delft, was a governing body in the Dutch city of Delft during the Dutch Golden Age. Comprised of influential citizens, it was responsible for local governance, administration, and decision-making. The council played a pivotal role in shaping the city's policies and development, contributing to Delft's prominence as an economic and cultural center during its heyday. With political changes in the late 18th century, the council's influence declined, but it remains a significant part of Delft's historical legacy. from 1675 onwards. In 1674, he lived at Dry Cooningen (Three Magi), Oude Delft number 123. During his lifetime, his wealth in real estate and bonds holdings grew from 90,000 to 475,000 guilders making him exceptionally wealthy. The family also owned an estate just outside Delft. The first six years of his major diary (1669–1713) which is now kept in the Koninklijke Bibliotheek describe his social excursions.Kees Kaldenbach, "Teding van Berkhout," A Rich Tapestry of Multimedia Sources, an Encyclopedic 2000+ Page Web Site on Johannes Vermeer & 17th Century Life in Delft," accessed November 18, 2023.

"In 1669, Van Berkhout was active in the art scene while living in The Hague. Like other discriminating connoisseurs of his era, he made a practice of visiting eminent artists in their studios, including those of several notable artists like Caspar Netscher (1639–1684) in The Hague, Gerrit Dou (1613–1675) in Leiden, and Vermeer in Delft. Additionally, Van Becrkhout explored the collections of art enthusiasts like his cousin Cornelis Boogaert (1640–1679) and others. Van Berkhout's diary entries not only reference specific artworks he saw in these studios and collections, but also describe his visits to "cabinets" or private collections in The Hague. Furthermore, during a trip to Dordrecht, Van Berkhout concluded his business by visiting Johannes van der Hulck, admiring his collection of 'tres Belles peintures.' It is speculated that during this visit, Van Berkhout saw works by Gerrit Ter Borch (1617–1681) and Gabriel Metsu (1629–1667), which were later sold in 1720 at the sale of Van der Hulck's heirs."Piet Bakker, "Painters of and for the Elite," in Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry, edited by Adriaan Waiboer and Eddy Schavemaker (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 97.

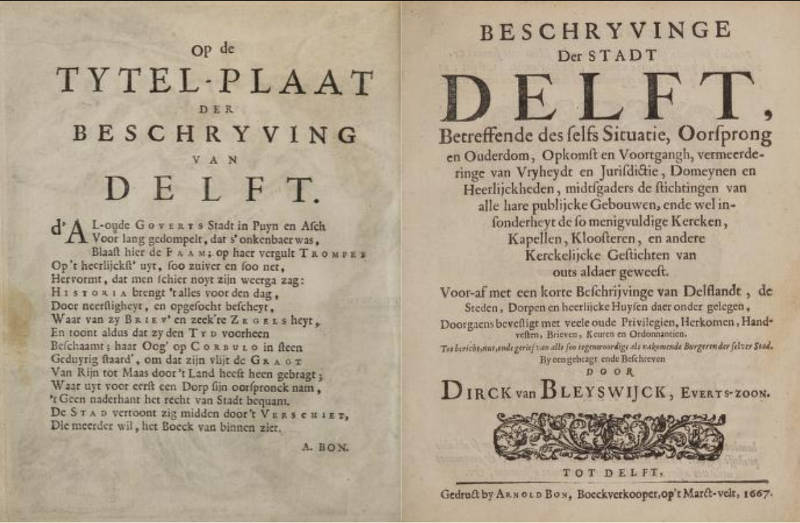

Bleyswijck, Dirck van. Beschryvinge der stadt Delft. Printed by Arnold Bon, bookseller on the Marct-velt, Delft, vol. 1 and 2, Delft 1667 and 1680.

Dirck van Bleyswijck

Printed by Arnold Bon, bookseller on the Marct-velt, Delft

vol. 1 and 2, Delft 1667 and 1680.

Beschryvinge der stadt Delft (Description of the City of Delft) is a historical work about the city of Delft in the Netherlands (fig. 32). This book was written by Dirck van Bleyswijck and published in 1667. It is significant for providing a comprehensive account of the history, governance, notable buildings, institutions, and customs of Delft during the seventeenth century.

Van Bleyswijck was a notable figure in Delft, and his work is often cited for its detailed descriptions and historical insights into the city's development, its economic and social life, as well as its cultural aspects. Beschryvinge der stadt Delft serves as an important source for historians and researchers interested in the Dutch Golden Age, offering a glimpse into the urban life of a prominent Dutch city of the period.

The book is valuable not only for its historical and cultural content but also for its illustrations, which include maps and views of the city, providing visual documentation of Delft's urban landscape in the seventtenth century. These illustrations are crucial for understanding the spatial organization of the city, its architecture, and its surroundings.

Beschryvinge der stadt Delft is part of a broader genre of city descriptions that were popular in the Netherlands during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, contributing to the historical and topographical knowledge of the Dutch Republic. One could still use the maps to get around the center of Delft.

Dirck van Bleyswijck's chronicles show how the thirty-five-year-old Vermeer's exceptional talent was noticed by his Delft contemporaries.

Very few surviving documents link Vermeer's name with his profession.

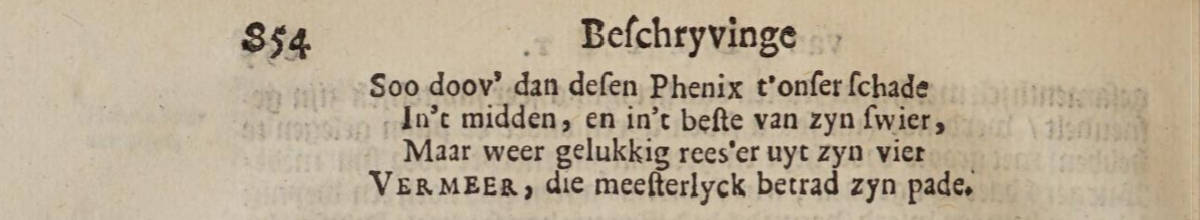

Dirck van Bleyswijck,

Published in 1667 (page 854, last stanza)

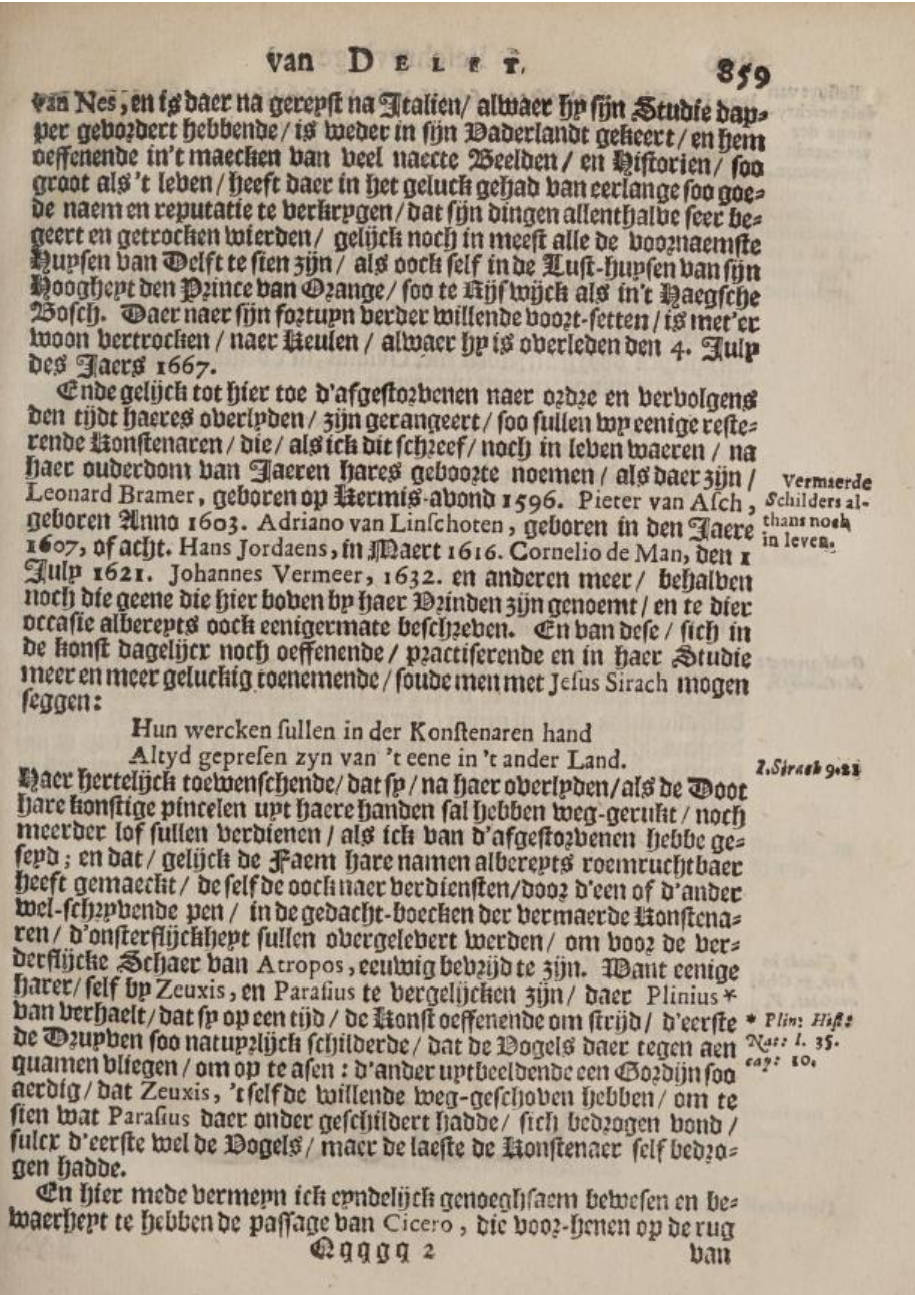

Vermeer's name is mentioned twice in Bleyswijck's book. The first (page 859) only mentions his name and birth, 1632, in a list of eminent Delft painters who were still alive at the time the book was being written.

The second mention is in a poem of eight stanzas written by Arnold Bon (before 1634–1691), Van Bleyswijck's publisher. The poem, "Op de droevige, en ongelukkigste Dood van den aller vermaardsten, en konstrycksten schilder, CAREL FABRICIUS," was composed in the honor of Carel Fabritius (1622–1654) who had died in the infamous ammunitions explosion of Delft.

Vermeer's name is lauded in the poem's last stanza. Seven stanzas are printed on page 853, the eighth stanza is printed on page 854.

Soo doov' dan desen Phenix t'onzer schade

In 'tmidden en in 't beste van zyn swier,

Maar weer gelukkig rees' er uyt zynvier

VERMEER, die meesterlyck betrad zyn pade.(Thus did this Phoenix, to our loss, expire,

In the midstand at the height of his powers,

But happily there arose out of the fire

VERMEER, who masterfully trod in his path.)

Art historians have long debated the significance of this brief tribute, attributing multiple meanings to it. The most obvious is that after the death of Fabritius, Vermeer was considered the foremost artist of Delft, a fact that challenges the long-held belief that Vermeer was neglected by his contemporaries. However, some earlier critics interpreted this as an indication that Vermeer had studied under Fabritius, a hypothesis that conflicts with the timeline of Fabritius' stay in Delft and Vermeer's youth. Fabritius moved to Delft in 1650 and died there in the infamous Delft Thunderclap of 1654. The belif that vermeer had apprenticed with Fabritius was baed stylistic affinities amd Bon's description of Vermeer as "following in the footsteps" or "emulating" Fabritius. However, both terms are vague enough to discourage reading in a master/apprentice relationship. Moreover, Fabritius seems to have joined the Delft Guild of Saint Luke more than a year before Vermeer, although he may have been working in Delft before he enrolled in the Guild. Importantly, there is little trace of Fabritius' style in Vermeer paintings until a few years after Fabritius had died in the infamous Gunpowder explosion of Delft while he was painting a portrait.

The Dutch art historian Albert Blankert was the first to note that the poem exists in two different versions, even though there is only one edition of the book. While the last line of the first version reads, "Vermeer, die meesterlyck betrad zyn pade" ("Vermeer who masterfully trod in his path") the line had, at some point, been changed to"Vermeer, die 't meesterlyck hem na kost klaren" ("Vermeer, who masterfully emulated him"). The changes seem to make it clear that Vermeer hadn't simply followed Fabritius' footsteps "but was able to paint as well as he and had succeeded him as Delft's leading painter." Vermeer's name is also mentioned on page 859 which lists painters active in Delft (fig. 34).

Dirck van Bleyswijck

Published in 1667 (page 859)

Arnold Bon, the printer of the book and the author of the poem, may have thought of the change himself. But according to Albert Blankert, "it is quite possible that it was suggested by Vermeer, who lived near Bon on the Markt (Market Square). Legal records show that Vermeer's obsession with precision was not restricted to his paintings. In two surviving documents he had his name crossed out and corrected, apparently because he found fault with the spelling. This is particularly remarkable given that Dutch contemporaries often spelled their names in various ways themselves. Vermeer presumably took written statements about himself and his art very seriously, and if he was not satisfied with the first version of the stanza he might well have persuaded Bon to change the typesetting."Albert Blankert. "Vermeer and his Public." in Vermeer, edited by Albert Blankert, Gilles Aillaud, and John Michael Montias, (Woodstock and New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2007), 165. The art historian Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. concurs with Blankert, observing that "the artist was hardly modest in his concepts."Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Ben Broos, Johannes Vermeer (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 52. At the very least he must have been familiar with stories about artists competing with each other. As far as he must have been concerned, Vermeer versus Fabritius could be added to the list of Apelles versus Protogenes, Raphael versus Michelangelo, Albrecht Dürer versus Lucas van Leyden, and Rembrandt versus Rubens."Ben Broos, "On Celebre Peijntre nommé Verme[e]r," in exh. cat. Johannes Vermeer. Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Ben Broos, London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995, 52. After all, The Art of Painting, was probably painted in or around 1667, when Beschryvinge der Stadt Delft was published, expressed Vermeer's high ideals about his trade and calling.

Sysmus, Jan (Johannes). Schildersregister (Register of Painters). 1669–1678.

Jan, or Johannes, Sysmus was a seventeenth-century Dutch physician who lived in Amsterdam. However, he is particularly known for a registry or list of painters he recorded during his time between 1669 and 1678 in which he recorded the names of various painters, along with brief descriptions or notes about their work.A. Bredius, "Het schldersregister van Jan Sysmus, Stads-Doctor van Amsterdam," in Oud-Holland 8 (1890), 1-17, 207-234, 294-313; 9 (1891), 137-49; 12 (1894), 160-71; 13 (1895), 112-20.) This registry provides valuable historical insights into the painters and their themes or subjects.

In a handwritten note, one of the most notable mentions in Sysmus's list is a "Van der Meer," which is believed to refer to the renowned Vermeer; "Van der Meer, Jonkertjes en casteelfjes. Delft, hiet Otto." (Van der Meer, small paintings of "dandies" and "little castles." Sysmus incorrectly recorded the artist's first name as "Otto," a common mistake given his frequent inaccuracies with first names. For example, he referred to Leonaert Bramer (1596–1674), the Delft painter and friend of Vermeer's family, as "Adriaen "Bramer."

Christoffel Jacobsz van der Laemen

c. 1640

Oil on panel, 57 x 74 cm.

Private collection

"What Sysmus meant by 'little dandies' becomes clear when we see that he employed the same word to describe the subjects painted by Caspar Netscher (1639–1684) and Eglon van der Neer (1634–1703). Concerning Christoffel van der Laemen (1606–1622) (fig. 35), he wrote: 'painted foolish little dandies [pinxit malle jonkertjes].' The subject matter of Hieronymus Janssen de Danser (1624-1693) he calls 'little salons filled with little dandies and damsels [zaletjes val jonkertjes en jojfertjes].' Cornelis de Bie, in his 1661 book on The Noble Liberal Art of Painting, characterized the paintings of Van der Laemen, as did Jan Sysmus after him, as "foolish little dandies." Van der Laemen specialized, says De Bie, in "the very nice depiction" of "courtship, dances, and other pleasurable ways of passing time by foolish little Dandies and Damsels ... who are rendered most pleasantly and charmingly." De Bie elaborates in a poem that Van der Laemen's young people are engaged in "foolishness and riotousness," "gorging and a great deal of other craziness," including "teasing and prancing," bass and viol playing, gambling, courting, dancing, "guzzling, swim[ming] in evil, liv[ing] above station," and this "without rule, without moderation [sonder reghel, sonder maet]." Sysmus indicates the themes of Gabriel Metsu (1629–1667), Gerrit ter Borch (1617–1681), and Michiel van Musscher (1640–1705) with just the word "juffertjes."

According to the late art historian Albert Blankert, "Vermeer's jonkers and juffertjes are the young people who appear in most of his works after 1666. Depictions of 'dandies and damsels' in inner rooms were a novelty introduced in the 1620s by Dutch artists like Dirck Hals (1591–1656), Willem Duyster (1599–1635) (fig. 36), and Pieter Codde (1599–1678). In their work, the figures are dressed according to the latest and costliest fashion. They amuse themselves with drinking, eating, music-making, and flirting. The owner and observer of such a painting could delight in the joys of youth."Albert Blankert, "Vermeer and his Public," in Vermeer, edited by Albert Blankert, Gilles Aillaud, and John Michael Montias, (Woodstock and New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2007), 32-22. The fact that Sysmus mentioned casteelties (little castles) as one of Vermeer's themes suggests that he might have been familiar with Vermeer's View of Delft.

Willem Duyster

c. 1623-1624

Oil on oak, 37.6 x 57 cm.

National Gallery, London

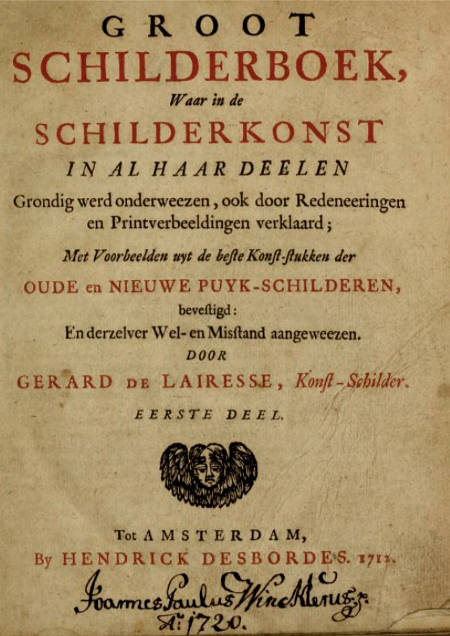

Lairesse, Gérard de. Groot schilderboek (The Great Book of Painting). 2 volumes. Amsterdam: Willem de Coup and Petrus Schenk, 1707. (PDF in orininal language; English version in 1778)

Gerard de Lairesse

Amsterdam: Willem de Coup and Petrus Schenk

1707

Gerard or Gérard (de) Lairesse (1641–1711) was a Dutch Golden Age painter and art theorist. His talents extended beyond painting to include music, poetry, and theater, evidencing his multidisciplinary skills. De Lairesse was influenced by the Perugian Cesare Ripa (c. 1555–1622) and French classicist painters like Charles le Brun (1619–1690), Simon Vouet (1590–1649), and authors such as Pierre Corneille (1564–1616) and Jean Racine (1639–1699). His significance grew in the period following the death of Rembrandt. Lairesse authored influential treatises on painting and drawing, including Grondlegginge Ter Teekenkonst (1701) and Groot Schilderboek (1707) (fig. 37).

The Groot Schilderboek is a comprehensive treatise on art and painting (fig. xx). It covers a wide range of topics related to painting techniques, composition, color theory, and artistic principles.While it served as a painter's manual on its surface, it is remarkably revealing about current social ideologies and their constitutive visual forms, delving into both the technical and conceptual aspects of painting. It had a substantial impact on art education and the development of academic art theory in Europe. Many artists and art students referred to this book for guidance and instruction. As a highly trained and talented painter, de Lairesse was deeply aware of the intricacies of composition and painting techniques, elaborating on them extensively. For example, he wrote "It is remarkable, that, though the management of the colors in a painting, whether of figures, landscape, flowers, architecture, & yields a great pleasure to the eye, yet hitherto no one has laid down solid rules for doing it with safety and certainty…and of color harmony,…good Union and Harmony, is not, to this Day, fixed on certain Principles. Meer Chance is herein our only Comfort."

One of the notable features of the book is its emphasis on a geometric approach to composition and perspective in painting. Lairesse believed that a solid understanding of geometry was essential for achieving harmonious and balanced compositions in art. It came at a time when there was a growing interest in the systematic study of art theory and technique, and contributed to the broader discussion on the role of art and the artist in society.

Lairesse's treatise was the first to fully elaborate on what are now recognized as classicist concepts. A basic premise is that subject and style need to be intimately connected. Fundemental to understanding his position, in his Groot Schilderboek de Lairesse distinguished two types of representations in the depiction of human figures in action: "Antique" and the "Modern." "'The Antique,' he wrote, 'persists through all periods, and the Modern constantly changes with fashion.' The painters of the modern mode depicted their figures in the dress and setting of their own time. Therefore, according to De Lairesse, ' Modern painting is not free,' but very limited, for it can ' depict no more than the contemporary' and thus ' it never lasts, but continually changes and becomes estranged'."Albert Blankert, "Vermeer's Modern Themes and Their Tradition," in exh. cat. Johannes Vermeer. ed. Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Ben Broos, (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 31. De Lairesse's treatise, which consistently connects art, refined conduct, and societal standing, effectively demonstrates various methods of holding glasses within the framework of his discussion on depicting figures in painting based on their social position. He notably demarks the differences between "people of fashion" and "ordinary people."

Nonetheless, Lairesse demonstrated flexibility in his thinking, making allowances that render his seventeenth-century discussion of genre scenes both rare and invaluable. He drew parallels between the passions elicited by genre pictures and those evoked by history painting, opeing the possibility of emotional depth in the lesser categoy of painting. He described gezelschapjes—in chambers, garden houses, and salons, with a few ladies sipping tea and gentlemen drinking wine—as little dramas, involving the passions of "entreating" and "refusing." By offering extended readings of such works, de Lairesse showed the degree to which any scene involving human interaction, however subtle, could yield an elaborate narrative. However, "he makes clear that not all 'modern' scenes could be rectified in this manner, only those depicting the upper echelons of society. Low-life genre scenes show nature worse than it is, while the next higher level portrays the reality of everyday life, and nothing more."Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., "Erudition and Artistry," in Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry, edited by Adriaan Waiboer and Eddy Schavemaker (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 25.

Late twentieth-century literary theorists have written at length and with conviction of the related notion of readers actively constructing the meanings of texts. As many art historians and film critics presently assert, the viewer has always been active in similar ways—the eye was and is a "performing agent."Alison McNeil Kettering, "Ter Borch's Ladies in Satin." In Looking at Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art: Realism Reconsidered, edited by Wayne Franits (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 110.