This study is inspired by the insightful article "Markt 54–56 (afgebroken)" by George Buzing and Gerrit Verhoeven, which explores the history of the Mechelen house, known as the childhood home and possible early painting location for Vermeer.George Buzing and Gerrit Verhoeven, Gerrit. "Markt 54–56 (demolished)," Achter de gevels van Delft. Accessed November 6, 2023. To my knowledge, the article introduces a pre-1885 photograph and three prints of Mechelen that have not been featured in mainstream publications about Vermeer until now.

On April 23, 1641, Vermeer's father, Reynier Jansz. Vos, bought a large and heavily mortgaged inn on the Markt (Old Dutch, "Grote Markt" known today in English as, Great Market Square or Market Square) called Mechelen. He paid 200 guilders in cash and assumed two mortgages, totaling 2,500 guilders. Mechelen had four fireplaces, indicating its size, one of the Markt's largest buildings. It was on the corner with the Oude Manhuissteeg (Old Mens' Alley),Opposite this alley and bridge, the Oude Mannenhuis (Old Men's House) was located on the Voldersgracht from 1411. This institution consisted of a number of rooms or houses around a courtyard and a chapel. From the middle of the 17th century, it was used as the Sint-Lucasgildehuis (Guild of Saint Luke Guild House). The entire complex was demolished in 1876 for the construction of a primary school, and it was reconstructed in 2007. a narrow alleyway that led to the Voldersgracht via a small bridge (Oudemanhuisbrug).

The fact that Mechelen also served as a tavern where people could stay overnight explains why it was larger than normal inns. Its strategic position, with the Stadhuis (Town Hall)on one side and the Nieuwe Kerk on the other, made it an ideal meeting place for Delft's citizens. Archival records reveal that local Delft artists also used to meet there for shop-talk and likely, conduct business, which was usual at the time. The Markt was the commercial center of Delft, with the Butter-Hall, the Weigh-House, and very close by the Meat-Hall, the Fish-Market and the Vegetable-Market, and, of course, many shops. The first recorded mention of Mechelen, presumably named after the Flemish town of the same name, dates back to 1540.XXXXXX The house must have been rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1536.

As with all neighboring houses on the north side of the Markt, the rear plunged straight down into the Voldersgracht canal. The narrow Oude Manhuissteeg ran alongside Mechelen, leading to a bridge over the canal at the rear. Unfortunately, Mechelen was demolished in 1885 to facilitate access to and from the Mark with no building now standing in its place (fig. 2 & 3) "despite a commemorative plaque claiming otherwise.

Moreover, in 1955 a memorial tablet was placed on the wall of the adjoining house at number 52 Markt to mark the spot where Mechelen supposedly once stood. The Delft sculptor Joh. Bijsterveld created the tablet bearing this inscriptionthat: "Here stood Mechelen House where the artist Jan Vermeer was born in 1632." However, the plaque has two inaccuracies. Firstly, Vermeer was not born in Mechelen, since his parents relocated there when he was nine years old. Experts on Vermeer contend the artist was likely born at the inn known as The Flying Fox on the Voldersgracht number 25-26, a stone's-throw away. Secondly, in format documents, Vermeer himself never adopted the name Jan. He was christened "Joannis" and consistently signed his deeds as Joannes, Joannis, or Johannis. The inscription faced criticism from various quarters in 1955, yet the foundation Delft binnen de veste (Delft within the ramparts) which devised the inscription, nevertheless decided the Christian name Jan had become more familiar.Michael van Maarseveen, Michael. Vermeer of Delft: His Life and Times. (Amersfoort: Bekking & Blitz uitg., 2006).

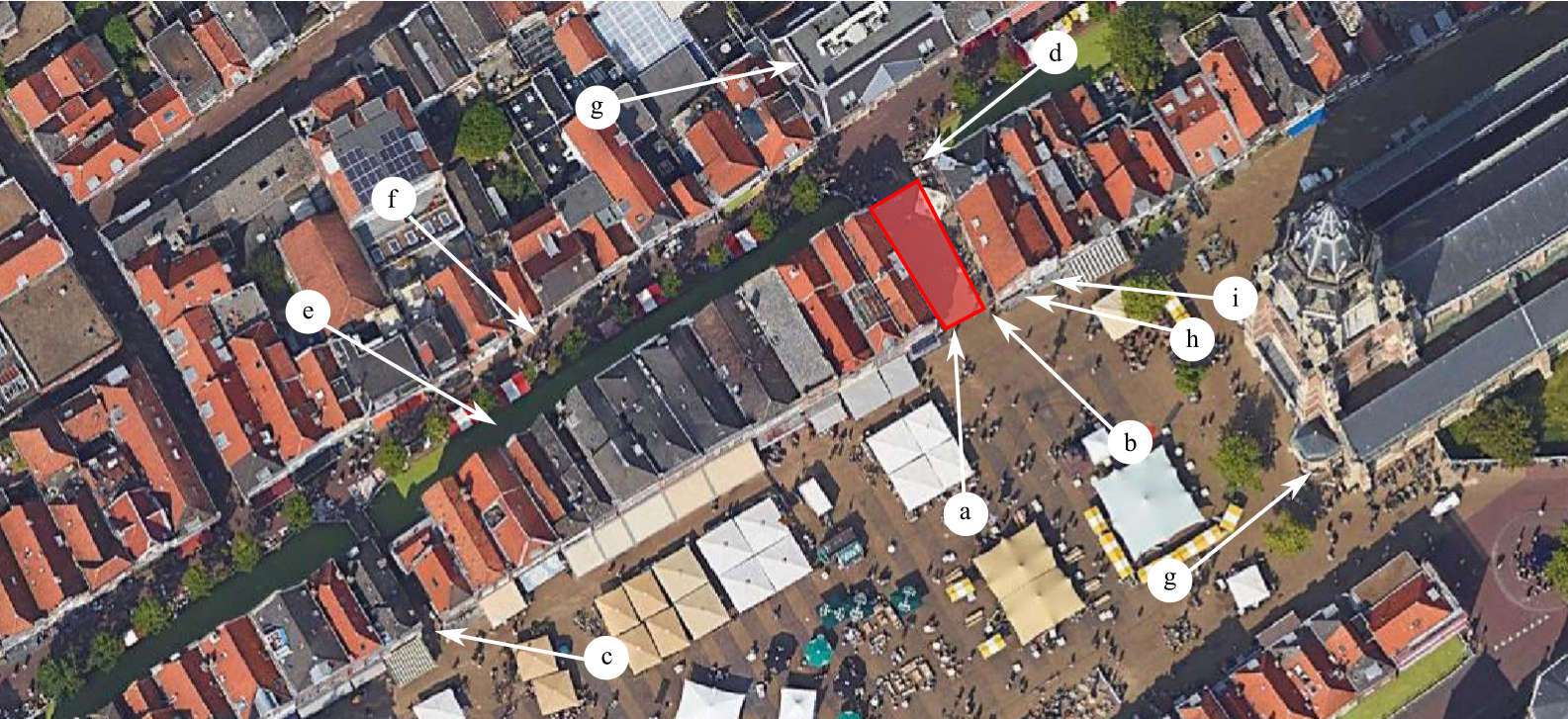

Photograph courtesy of Tatiana Golovko

a. former location of Mechelen (in red)

b. Oude Manhuissteeg

c. Bonte Ossteeg

d. Oudemanhuisbrug

e. Voldersgracht canal

f. Voldersgracht

g. Nieuwe Kerk (New Church)

h. Markt 62

i. Markt 64

j. Stadhuis (Town Hall)

1582

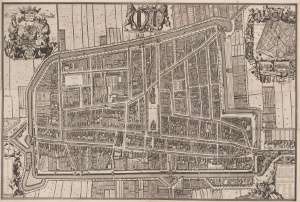

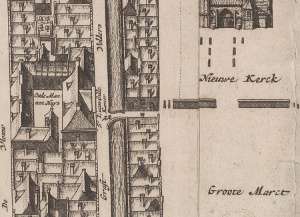

In 1582, a bird's-eye view map of Delft was published in Georg Braun and Joris Hoefnagel's monumental Civitates Orbis Terrarum (fig. 6). The map was subsequently reproduced into the atlases of Ludovico Guicciardini (1521–1589) and Johannes Janssonius (1588–1664).

(inscribed "Delphium urbs Hollandiae cultissima, ab eiusdem nominis fossa vulgo, Deelft appellata ")

Georg Braun & Joris Hoefnagel

1582

Copper engraving, 35.5 x 48.5 cm.

Universiteitsbibliotheek Utrecht

Georg Braun & Joris Hoefnagel

1620

Copper engraving, 35.5 x 48.5 cm.

Georg Braun & Joris Hoefnagel

1620

Copper engraving, 35.5 x 48.5 cm.

Braun (1541–1622) and Hoefnagel (1542–1601) must have followed an older, now unknown map as the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk is represented with the apple-shaped spire (fig. 7) which went up in flames in the Great Fire of 1536. It should be remembered that the Braun /Hoefnage map may be consulted primarily as a topographical reference, focusing on the town wall and its main features: the gates and towers, as well as public and religious buildings. The architectural features of the individual buildings are often represented with limited accuracy. For example, the chapel of the Oude Mannenhuis (fig. 8) is not set parallel to the street but is incorrectly rotated a few degrees and set back from the street.The walls of the chapel survived the great fire of 1536. Thereafter, it was restored, and in 1661 partially modernized for the St. Luke guild. However, with regards to individual, private houses such as Mechelen, the map has little more than nominal value.

Georg Braun & Joris Hoefnagel

1620

Copper engraving, 35.5 x 48.5 cm.

It should be noted that should the mapmaker have intended to show all the narrow streets and alleys of the town, it was often necessary to draw them wider in order to "see" the pavement and create enough room to inscribe their names on them. This principle applies to all bird's-eye view maps, including the Kaart Figuratief and those published by Johan Blaeu (1596–1673). If the width of the Oude Manhuissteeg in the Braun /Hoefnagel map had been accurately drawn, the alleyway's pavement would not have been visible (fig. 9).

A medieval city plan of Delft demonstrates that, unlike the houses shown in the Braun/Hogeberg map, houses actually had their short side to the street. Delft originated in the county of Holland. The Count of Holland owned the land, which was divided into parcels. Each parcel's occupant was obliged to pay a yearly rent (known as tijns ). Rent collection followed a register that was used over several years. Several registers have survived. The rent amount was based on the width of the parcel. The parcels of the Kadastrale Minuut of 1832 (fig. 28) are almost same as the were in 1461-1465, thus, confirming the system of deep parcels with relatively narrow fronts, which had been devised to maximize use of land within the limits of the city boundaries.

In any case, their primary aim of atlases like Braun/Hoefnagel's was not to produce topographically accurate landscapes, but to present a narrative in an aesthetically pleasing visual form, akin to an entertaining guidebook.

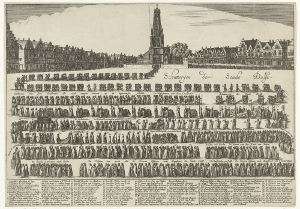

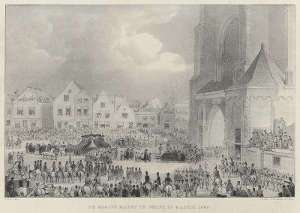

1625–1626

Click here to download a high-resolution scan of the Funeral of Prince Maurits in 1625 by Gillis van Scheyndel I.On 20 September 1625, a long funeral procession passed across the Delft Market in the direction of the Nieuwe Kerk. It was the funeral of Prince Maurits who died on April 23, 1625. The stadtholder's embalmed corpse was put away in The Hague until it was transported to Delft in a black-clothed barge on 16 September. There it stayed in the Prinsenhof until the funeral on 20 September. Burial was a very costly affair. The bier with the Prince's corpse was preceded by eight halberdiers; they carried their weapons pointed down. Senior officers from the State army walked around the box,over which a cloth decorated with Maurice's weapons was draped. One of them was Justinus van Nassau, governor of Breda and Maurice's half-brother. Family members, including Frederik Hendrik, walked behind the cavalry's rhythm masters. The Winter King Frederick V and his retinue came close to him. Behind it the Count of Nassau. The ambassadors of France and Venice were closely involved followed by pages and lackeys, who were less in line than the other participants. The last part of the procession consisted of members of the States General and the Council of State, followed by representatives of regional and urban authorities. For example, almost 12,000 guilders were spent on the mourning clothes of the members of the royal household. Prince Maurits, 2nd son of Prince William of Orange, died of liver cancer on April 13, 1625. From: "Princes of Orange and Nassau Interment of Prince Maurits of Orange," The Houses of Orange and Nassau, accessed Novenber, 2023.

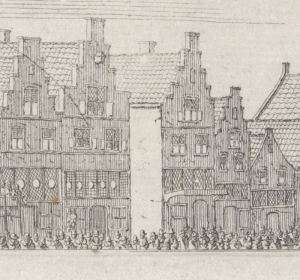

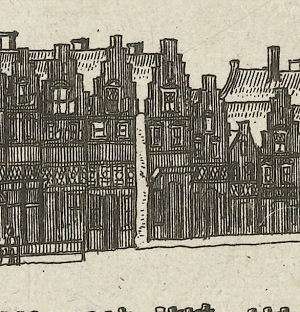

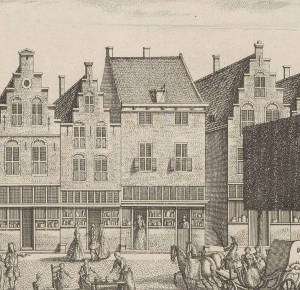

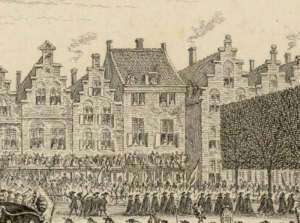

Although the first mention of what would eventually be known as Mechelen dates back to 1540, the first reliable visual representation is on the top-left-hand sheet (fig. 10) of a four-sheet engraving illustrating the funeral of Prince Maurits in 1625, published between between 1625 and 1626 by Haarlem etcher and draftsman Gillis van Scheyndel (c. 1595–c. 1660). The sheet pictures a long row of the typically narrow buildings located on the north side of the Markt in Delft.

From Atlas van Stolk

Printmaker: Gillis van Scheyndel (I)

Publisher: Claes Jansz. Visscher (II), Amsterdam

1625

Engraving on paper, 21.1 x 50.5 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

From Atlas van Stolk

Printmaker: Gillis van Scheyndel (I)

Publisher: Claes Jansz. Visscher (II), Amsterdam

1625

Engraving on paper, 21.1 x 50.5 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

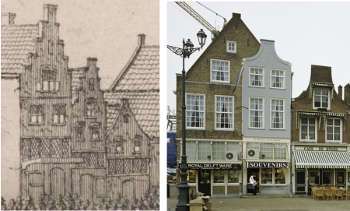

In many subsequent depictions of this area, Van Scheyndel's Mechelen can be instantly identified because it is located on the east corner of Markt and the Oude Manhuissteeg (fig. 11). In many perspectival views, the alleyway is marked by a rectangular patch of empty wall that belongs to the side of the building on the opposite (east) corner of the Oude Manhuissteeg, currently Markt 62.

The buildings facing the Markt in Van Scheyndel's print vary in proportion, and, with only two exceptions, feature stepped gables. The width and height of the façades along with the variety and arrangement of windows vary considerably, enough to suggest they were observed by the draftsman. This supposition is supported by two observations. First, the number of buildings—14—flanked by the two alleys that connect the Markt to Voldersgracht (Oude Manhuissteeg and Bonte Ossteeg) is nearly the same as the ones existing today—13—excluding the demolished Mechelen. Second, the relative proportions and some of the architectonic features of the three houses opposite Mechelen on the Oude Manhuissteeg appear to mime those standing today. The curious merging of the façades seen today (fig. 13), the disposition of the windows and their comparative heights suggest that Van Scheyndel's rendition is not a flight of artistic fantasy. Furthermore, the building to the right of the two just mentioned is more squat than its two companions to the left and, as today, it does not have a stepped gable but two gently sloping curves. Thus, the individualized treatment of the façades as well as corresponding number of buildings would suggest that the building that appears in the location of Mechelen is probabaly based on observation, although exactly to what degree it is impossible to know.

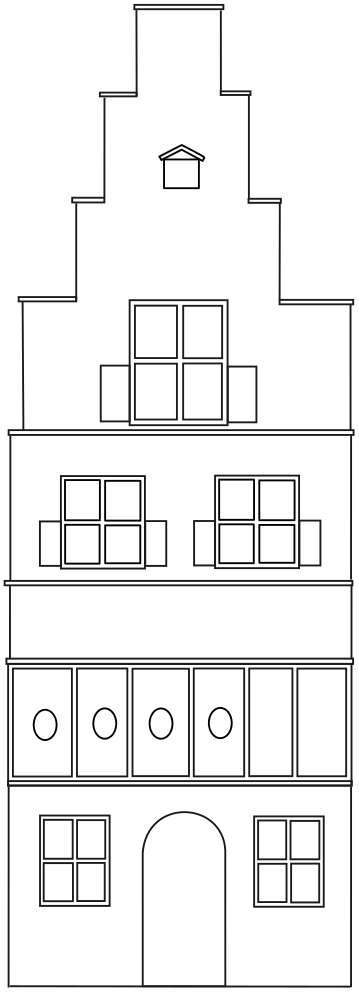

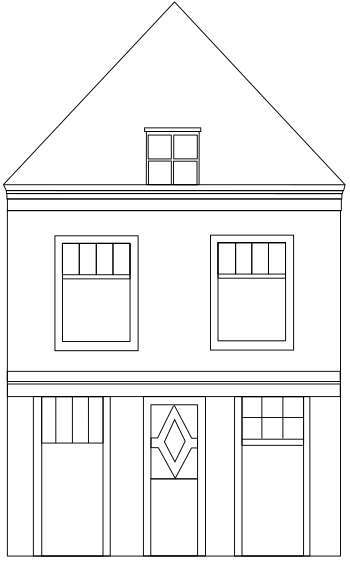

In Van Scheyndel's rendering, Mechelen has two floors, a loft, a stepped gable, and a winch at the top of the façade used for lifting heavy or bulky items to the top floors. The ground floor shows a central, arched doorway flanked by two windows, each with four lites. Directly above is a row of six latticed windows. On the second floor, there are two large windows each with four lites and open shutters on the bottom lites. The loft has an even larger window with four lites and, again, open shutters on the bottom lites. Given the rather uncertain perspective of the drawing it is difficult to judge the size of Mechelen relative to the adjacent buildings but it seems to be somewhat wider than the first two buildings to the left. Certainly, the proportions of the roof and stepped gable are too steep and the whole façade is too slender. The Oude Manhuissteeg is depicted as somewhat wider than one might expect.

Van Scheyndel's foremost intention was to represent the funeral parade and only secondly to provide a detailed, topographically correct reproduction of all the houses, even though they are rendered quite well. However, many shop fronts are inaccurately drawn. The arched top of Mechelen indicates that it may have been part of a wooden frame—arched entrances in brickwork are very unlikely for townhouses. Shop fronts with a separate entrance and windows were introduced in the eighteenth century when sash windows became popular. Above the doorway and ground-floor windows is a row of windows with leaded glass, which allowed more light to enter into the ground floor. Such rows were certainly common features of shop fronts, but they were always combined with the door and windows beneath in one wooden frame, or casing, and not separated by brickwork as appears in Van Scheyndel' rendering. Mechelen also exhibits this inaccuracy. Not a single example of Van Scheyndel' configuration can be seen in earlier representations of shop fronts, nor has any example survived in the Netherlands.

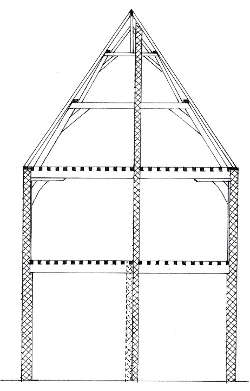

Markt 62 and 64 form one house that was (partly) divided in two. A reconstruction section drawing (fig. 16) which appears in Wim Weve's Huizen in Delft in de 16de en 17de eeuw (Houses in Delft in the 16th and 17th Centuries) shows a dividing wall in line with the roof's ridge, existing only on the ground floor and first floor, or a higher story. Markt 62/64 was probably built around 1575-1600.Weve, Wim. "Two Bay Houses." In Huizen in Delft in de 16de en 17de eeuw (Houses in Delft in the 16th and 17th Centuries), (Rotterdam: NAi Boekverkopers, 2023). It was later altered in order to create two shops of the exact same width, which required shifting the dividing wall on the ground floor a few inches to the right. At the same time the shifted wall would have had to extend to the rooftop, just beside the ridgeline with its braces. The original location of the (shorter) dividing wall is still identified by marks on the oak beams of the ceiling. The bell-shaped gable of Markt 64 suggests this modification took place in the eighteenth century. A photograph taken from the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk (fig. 15) clearly demonstrates that Markt 64 is not a standalone house, and its façade and the short section of roof are an architectural whimsy.

In conclusion, the Mechelen we see in Van Scheyndel' print is probably based to some degree on observation and provides us with some photographich evidence as to its main architectural features, but various details indicate it was not drawn with topographical perfection in mind. This, however, is understandable when we consider both its primarily commemorative function as well as the fact that the scene was observed from the doorstep of the town hall, with both the Oude Manhuissteeg and Mechelen situated at a significant distance. The same lack of topographical precision can be said of the house opposite Mechelen.

Created by Timothy De Paepe <https://3dtheater.wordpress.com/>

1649–1651

Click here to download a high-resolution scan of the Funeral of Prince Maurits in 1625 by an anonymous engraver, after Gillis van Scheyndel (I)

In circa 1649–1651, another commemorative engraving of the funeral of Prince Maurits in 1625 (fig. 18) was published by an anonymous printmaker, after Van Scheyndel. Although it follows the architectonic scheme of the Van Scheyndel print, it is far less detailed (fig. 19) and contributes nothing to our knowledge of Mechelen.

Atlas van Stolk 1626

Printmaker: anonymous, after Gillis van Scheyndel (I)

1649–1651

Etching on paper, 27 x 38.4 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Atlas van Stolk 1626

Printmaker: anonymous, after Gillis van Scheyndel (I)

1649–1651

Etching on paper, 27 x 38.4 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

1675–1678

Click here to download a 16,000 x 12,000 (100 MB) scan of the Kaart Figuratief.

In 1675, the former mayor of Delft, Dirck Evertsz. van Bleyswijck (1639–1681), author of the foundational book on Delft, Beschryvinge der Stadt Delft (Description of the City of Delft), was commissioned by the municipality to produce a map of Delft with accompanying images of buildings and cityscapes, which is known as the Kaart Figuratief (fig. 20). When the map was ready in 1678, the comprehensive set included a birds-eye view of Delft from the west, Delfshaven seen from the Maas, 22 images of buildings, two maps of Overschie and Delfshaven, four family coats of arms of Delft mayors, and a short text with a description of the city of Delft.

While the most important buildings in Delft are represented with adequate fidelity, the individual features of many domestic dwellings were likely standardized to one degree or another. Art historical research suggests there are generally fewer houses in the northern and southern parts than existed in reality (Noordeinde, Lange Geer, southern part of the Oude Delft.) The map is effectively compressed horizontally, constrained by the dimensions of the copper plates used for the engraving. Unfortunately, although the Oude Manhuissteeg and the Bonte Ossteeg are clearly indicated, it is difficult to count the number of houses between them. Nonetheless, the delightful birds-eye-view allows the spectator to clearly view the position of Mechelen with respect to its immediate environs (fig. 21), including the Markt, the Oude Manhuissteeg, Voldersgracht and the Guild of St Luke. From what is discernible, Mechelen is shown with a gabled roof and two chimneys. This suggests that there may be more fireplaces within the building than chimneys visible on the roof.

Published in Delft by Dirck Evertsz. van Bleyswijck

1675–1678

81.5 (82.5) x 124.5 (125.5) cm.

Published in Delft by Dirck Evertsz. van Bleyswijck

1675–1678

81.5 (82.5) x 124.5 (125.5) cm.

c. 1730

Click here to download a high-resolution scan of Leonard Schenk's View of the Delft Market Square

Printmaker: Leonard Schenk

Intermediary draughtsman: Abraham Rademaker

Publisher: Leonard Schenk

c. 1730

Etching on paper, 57 x 98 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Printmaker: Leonard Schenk

Intermediary draughtsman: Abraham Rademaker

Publisher: Leonard Schenk

c. 1730

Etching on paper, 57 x 98 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

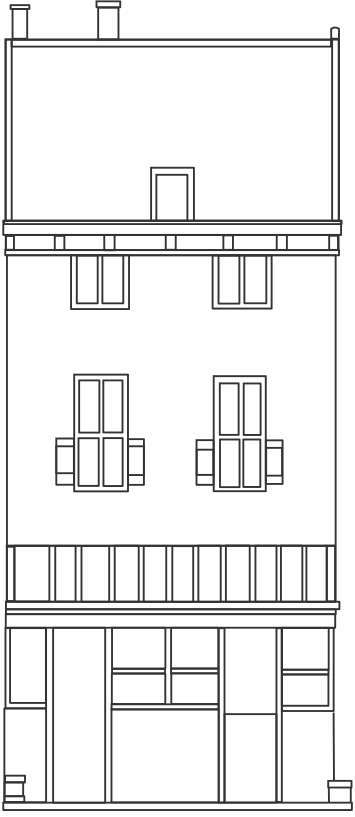

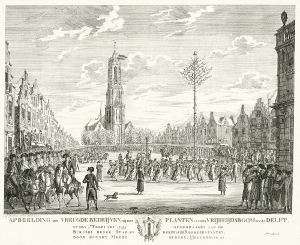

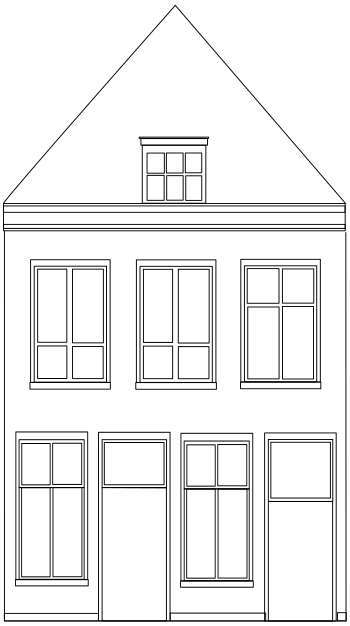

Circa 1730, the printmaker Leonard Schenk (1696–1767), a Dutch engraver, editor, and bookseller, published an engraving of the north side of the Markt (fig. 22) after a drawing made by Abraham Rademaker (1677–1735), in which Mechelen is portrayed frontally (fig. 23). Schenk made two prints of Delft as part of a series with large Dutch town views; the other print is a view of Delft from the south, as depicted by Vermeer in his View of Delft. In both cases the prints follow exactly the drawings of Rademaker, and in both cases the image is compressed horizontally in order to show more than the dimensions of the copper plates (and maximum size of hand made paper sheets) would allow without needing to reduce the buildings' size or create excess space above them.

The horizontal "compression" of the buildings seen in the Rademaker/Schenk prints is starkly apparent when we compare one of the façades (fig. 25) to its surviving counterpart at Markt 30 (fig. 26). The windows of the second story still have the same arches as they did in the seventeenth century, and were only modernized as sash windows. The surviving windows of the third floor, i.e., the attic, appear considerably wider than those of Rademaker/Schenk print, and yet we know that they have the same widths and positions as they did in seventeenth century, a fact demonstrated by the patterns of extant masonry.The gable at the second floor (the attic) of Markt 30 retains part of the original 17th century brickwork. To the left of the window, about one meter above the horizontal stone band to right of the window it is possible recognize the 17th-century masonry by the presence of klezoren the small square bricks, one-quarter of the length of a brick, disposed in a vertical row alongside the edge of the gable and window openings. During modern modifications of the gable with a cornice the old masonry was retained as much as possible. New masonry had to be made only at the corners. The masonry with the stone band proves that these small windows have maintained their original width. The original window sill was raised just a few centimeters. Originally it rested on the lower protruding stone band and was in line with the higher, not protruding, stone band.

As for the façade of Mechelen, it is considerably different from the previous renderingby Van Scheyndel in both proportion and architectural features. Instead of one ground floor door, the Schenk print depicts two side entrances. The latticed windows of the ground floor directly above are much lower. Above these, there are two windows with four lites and a pair of open shutters on the lower lites. Above these are two other windows, which may belong to the loft. The roof is no longer the gable type that slopes to the sides. Instead, the plane of the roof rises from the articulated cornice on the building's front side and then slopes downward behind the front façade, vaguely resembling the structure of the so-called salt-box roof. At first glance, the rising and descending planes of the roof do not appear extensive enough to span the entire depth of Mechelen, but the back slope of the roof may have joined a gable-style roof, out of sight in the print (fig. 25). Such hybrid roofs are occasionally detected in birds-eye-view of the Van Bleyswijck print (fig. 24). Whatever the case, the Schenk building is frequently mentioned, in Vermeer-related literature.

But, how true to life is Schenk's print, and what can we deduce from the rendering of the house that stands in the place of Mechelen?

It is theoretically possible that during the one hundred years that separate the Schenk and Van Scheyndel renditions, the actual buildings of the Markt were remodeled. Certainly, the individual façades of the Schenk version are so carefully articulated that they might induce the casual observer to accept them as factual. To convince us of his perspective illusion and delight the eye of the beholder, the skillful draftsman meticulously catalogued minute incidences of architecture and urban life: crawling vegetation, decorative garlands, metal anchor rods, exterior shelves stocked with merchandise. Buildings are fitted with a variety of differently configured windows, upper story dormers, pulleys, and series of exterior shelves stocked with merchandise on the ground floor.

However, by any standard, there are glaring inconsistencies with reality. First, there are only nine buildings between the Oude Manhuissteeg and the Bonte Ossteeg when we know that there were at the very least 13. Second, the first three buildings to the right of the Oude Manhuissteeg bear little or no resemblance to those depicted by Van Scheyndel or to the corresponding surviving buildings (fig. 10 & 11), which are surprisingly in agreement despite the nearly 400 years separating the two renditions. Third, the perspective is impossible: it would not be possible to bring both the Nieuwe Kerk and the Stadhuis within the print's extremely compressed field of view. Clearly, the illustration primarily aims to provide a view of Delft's prosperous citizens engaged in pleasant pastimes in the midst of the picturesque setting of the Markt, in a sort of urban paradise.

1742–1801

Click here to download a high-resolution scan of Georg Balthasar Probst's View of the Nieuwe Kerk, Delft

Georg Balthasar Probst (1732–1801) was a German engraver and publisher based in Augsburg. Many of his family members also worked as printers and publishers at the same firm in Augsburg. He was particularly known for his Vues d'Optique (optical views) of cities, which were meant to be seen through an optical box fitted with a convex lens in order to enhance the sense of three-dimensionality. Common features of the Vues d'Optique are dramatic perspectival views and bright colors. "The Getty Research Institute notes that street performer would set up viewing boxes—also known as zograscopes, optiques, optical machines, or peepshows—with a series of prints of prints giving a pictorial tour of famous landmarks, dramatic events and foreign lands.Grand Tour travelers also purchased Vues d’Optique as souvenirs, which were later viewed at home as a parlor activity.""View, Russia, St. Petersburg, Vue d’optique, Antique Print, Probst, Augsburg, 18th Century," George Glazer Gallery, accessed, november 6, 2023. When viewed through the apparatus, which was printed in reverse, would appear in its correct orientation. In fact, the view of the Markt is an example of Probst's Vue d'Optique, as evidenced by the reversed title at the top of the print.

The façade of the building corresponding to Mechelen displays two or possibly three stories, each with three windows and, curiously, no ground-level entranceways (fig. 23). However, the roof seems to be similar to that of Schenk's print. Despite the crude drawing and perspective, there are 13 buildings between the Oude Manhuissteeg and the Bonte Ossteeg, a detail that is probablyn ot a coincidence. This accuracy likely stems from Probst's use of earlier prints as references. Evidently, Probst did not emphasize the individual features of the buildings, as topographical precision was not the main objective of such prints (fig. 22).

Georg Balthasar Probst (possibly), after Isaac van Haastert

1742–1801

Etching on paper, 29.2 x 42.2 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Georg Balthasar Probst (possibly), after Isaac van Haastert

1742–1801

Etching on paper, 29.2 x 42.2 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

1752

Click here to download a high-resolution scan of Simon Fokke's The Funeral Procession of Willem IV in Delft, 1752.

In 1752, Simon Fokke, a Dutch designer, etcher, and engraver, published an etching of the funeral procession of Willem IV in Delft, 1752. Fokke expedited the process by lifting the background from Leonard Schenk's view of the Markt (fig. 24). The architectural features of the buildings are shoddily drawn. They add little to the print from which they are derived apart from smoke lazily rising from a few chimneys and figures peering out from numerous windows to the historic procession below. Apparently, a temporary gallery had been erected just above the ground floor stretching along the entire length of the façades (fig. 25) allowing more spectators a better vantage point.

Atlas van Stolk

Printmaker: Simon Fokke (mentioned on object)

Intermediary draughtsman: Simon Fokke Publisher: Frans Houttuyn 1752 Etching on paper, 18.6 x 29.8 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Atlas van Stolk

Printmaker: Simon Fokke (mentioned on object) Intermediary draughtsman: Simon Fokke Publisher: Frans Houttuyn 1752 Etching on paper, 18.6 x 29.8 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

1795–1797

Click here to download a high-resolution scan of Johannes Jelgerhuis' View of the Nieuwe Kerk, Delft

Around 1795–1797, the printmaker Johannes Jelgerhuis (1770–1836), a Dutch painter and actor, published an engraving of the Markt (fig. 26) which illustrates a jubilant celebration called ‘Feest bij het planten van de vrijheidsboom,'1795 (The Planting of the Tree of Freedom in Delft). The left side of the print shows the row of houses on the north side of the Markt in strongly accelerated perspective. In the very foreground what is most likely the Bonte Ossteeg can be clearly made out (fig. 27). The first façades are carefully rendered showing the same sort of protruding pentices visible in the Probst print, from which citizens enjoy the spectacle.

Although there is no evidence of the Oude Manhuissteeg, one of the façades is comparable in various features to the Mechelen that appears in the earlier View of the Nieuwe Kerk, Delft, by Georg Balthasar Probst. Both have the three floors, the top two of which have three windows. Moreover, neither rendition shows a step-gabled roof, and both are fitted with a pentice that projects from the ground floor. However, in the Jelgerhuis view there are only nine or ten buildings between the Oude Manhuissteeg and the Bonte Ossteeg, while in the Probst view there are thirteen. While both versions exhibit elements that effectively coincide with known architecture of the north side of the Markt, it is evident that neither artist was particularly concerned with topographical accuracy, and so, both may be considered artful weaves of fact and fiction.

Printmaker: Johannes Jelgerhuis

1795–1797

Engraving on paper, 33.5 x 41.7 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Printmaker: Johannes Jelgerhuis

1795–1797

Engraving on paper, 33.5 x 41.7 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

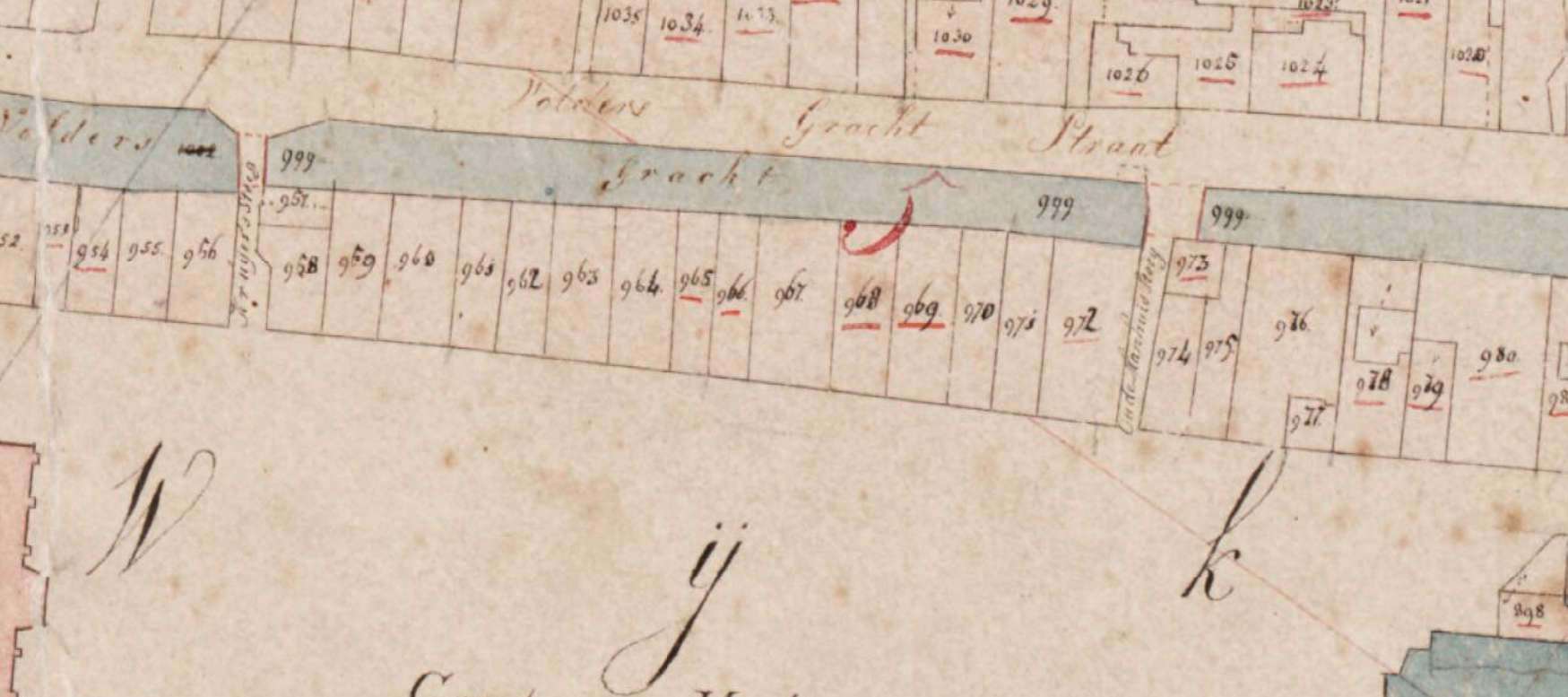

1811–1832

Click here for high-resolution image of the Kadastrale Minuut

Between 1811 and 1832, the municipality of Delft drew up a detailed cadastral plan of Delft, referred to as the Kadastrale Minuut (fig. 28), which was used for the purpose of taxation. The historic map allows us to examine with confidence the exact geography of the town as it was in 1832. It has often been referenced in Vermeer literature because, according to Kees Kaldenbach, the city plan had probably changed little from the seventeenth century. By 1832 measurements had become much more precise and the old towns were not yet affected by the arrival of the railway or the motorcar.

(Cultural Heritage Agency, Amersfoort / MIN08034C01)

1828

In 1828, Gerrit Lamberts (1776–1850) made a sketch of the Oude Manhuissteeg facing the Guild of St. Luke (fig. 30). Lamberts was a Dutch artist and curator of the Rijksmuseum when it was located in the Trippenhuis. Born in Amsterdam, he was also a watercolorist, draughtsman and engraver, known for his landscapes, architectural views and watercolors of art galleries. He also made more than one hundred accurate topographical views of Amsterdam and its surroundings.

The right-hand side of Lamberts' drawing shows the east side of today's Markt 62, and on the left-hand side is the west side of Mechelen. However, the true subject of the drawing appears to be the façade of the Guild of St. Luke (the guild of artists and artisans) that, being a painter himself, may have stimulated Lamberts' curiosity. Along the Mechelen wall two steps leading to a small doorway with a wrought-iron handrail, a small window is visible in the distance with four lites, one of this window's lower shutters is ajar. On the opposite wall a side window can be seen about half way down the alley. Closer to the viewer, Lambert has drawn a smallish, unadorned opening at the foot of the wall that allowed air and a little light to enter into the building's basement. Curiously, this modest basement window remains today. (fig. 29).

Interestingly, Mechelen, like all houses around the Markt, originally featured—and most still retain—a split-level ground floor. The drawing by Lamberts shows the step to the room above the cellar, in Dutch a so-called opkamer (literally: up room). From the house opposite this scene a window of the cellar is visible (fig. 30).

Gerrit Lamberts

c. 1820

Graphite, pen and brown ink, brush and gray ink, 24.9 x 19.3 cm.

Gemeentearchief, Delft

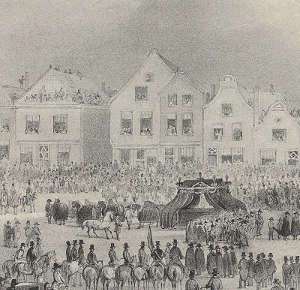

1849

Click here to download a high-resolution scan of Antony Last's Markt of Delft, on 4 April 1849

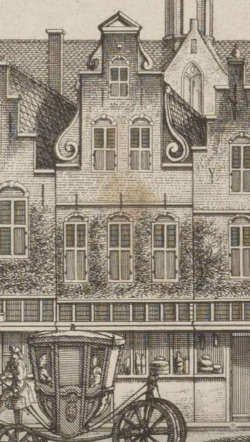

In 1849, Carel Christiaan Antony Last (1808–1876), a Dutch printmaker, published a somber lithograph of the northwest corner (fig. 32) of the Markt on April 4, 1849, picturing the funeral procession of King William II. To the right of the imposing Nieuwe Kerk entranceway, are represented 7 façades, and to the immediate left, the Oude Manhuissteeg and then Mechelen. Standing to the right of the Oude Manhuissteeg are two façades of today's Markt 62 and Markt 64 (fig. 12), which, oddly, seem to merge into a single façade, despite being covered by a single gabled roof. This curious double façade, as well as the squat building to the immediate right, are reminiscent of the those that stand today (fig. 11 & 12). This testifies to the fact that the lithograph was at least partly based on direct observation.

Mechelen differs from previous representations (fig. 33) in certain details The façade is relatively squat and appears similar to the Last print, and the ground floor has an expansive central doorway and two lateral windows. The second floor, with two large windows, is crowned by a cornice and a hip roof.

Kees van der Wiel, from Achter de gevels van Delf, argues that Last's representation of Mechelen is incorrect for featuring a single door flanked by two windows. Instead, the Schenk print and historical photographs both show two front doors. Van der Wiel maintains that since it was referred to as a double house in 1768, it would likely have had two doors in 1849 as well.

Carel Christiaan Antony Last

1849

Lithograph on paper, 22.1 x 29. 2 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Carel Christiaan Antony Last

1849

Lithograph on paper, 22.1 x 29. 2 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

1858–1859

About a decade after Last's publication of his Markt of Delft lithograph on 4 April 1849, delicately colored lithograph by Christiaan Bosa was published (fig. 34) which depicts the Markt dominated by the soaring Nieuwe Kerk in the center. To the church's left, past a group of trees appears the same double façade observed today and also seen in the same form in the pre-1885 photographs (fig. 35). The narrow Oude Manhuissteeg is marked by a dark gap. Directly to the left of the gap stands Mechelen, which at first glance appears similar to the Last print. The roof, as well, is the same hip type, with a central dormer window. The ground floor features a window, a door, another window, and a second door from and another door while the upper floor has three windows on the upper floor, different from Last's print.

These discrepancies raise questions.

First, the Mechelen of the Bos print is, although not highly resolved in detail, strikingly similar to Mechelen as it appears in pre-1885 photographs that were most probably made after Bos' lithograph. Thus, either Mechelen underwent remodeling in the span of about 10 years separating the two prints, or alternatively, Last's version was less precise. Considering that the combined Markt 62 and Markt 64 façades are represented with demonstrable accuracy, it is puzzling why Last would have paid less attention to the uncomplicated façade of Mechelen. In any case, the accuracy of Mechelen in the Bos print is confirmed by all the pre-1885 photographs where Mechelen is distinctly visible.

Draftsman: Christiaan Bos (1835–1918)

Lithographer: Gerardus Johannes Bos (1825-–)

1858–1860

Publisher: P.W.M. Trap, Leiden (druk litho); J.J. van Gessel, Delft

Lithograph on paper, 21.4 x 14.9 cm.

Delft University of Technology

Draftsman: Christiaan Bos (1835–1918)

Lithographer: Gerardus Johannes Bos (1825–1898)

1858–1860

Publisher: P.W.M. Trap, Leiden (druk litho); J.J. van Gessel, Delft

Lithograph on paper, 21.4 x 14.9 cm.

Delft University of Technology

Photographs before 1885

Luckily, at least three photographs of Delft's Markt were taken before Mechelen was demolished in 1885 (fig. 41, 42 & 45), revealing the building's simple façade.The gable at the second floor (the attic) of Markt 30 retains part of the original 17th century brickwork. To the left of the window, about one meter above the horizontal stone band to right of the window it is possible recognize the 17th-century masonry by the presence of klezoren the small square bricks, one-quarter of the length of a brick, disposed in a vertical row alongside the edge of the gable and window openings. During modern modifications of the gable with a cornice the old masonry was retained as much as possible. New masonry had to be made only at the corners. The masonry with the stone band proves that these small windows have maintained their original width. The original window sill was raised just a few centimeters. Originally it rested on the lower protruding stone band and was in line with the higher, not protruding, stone band. Photographs taken after 1885 are distinguishable as Mechelen is no longer visible, but for the fact that in 1886 a bronze statue of Hugo Grotius by Franciscus Leonardus Stracké was erected in front of the Nieuwe Kerk (fig. 53).

Even though Mechelen itself was not the point of interest of any pre-1885 photographer, these rarely published photographs reveal what Mechelen was like before its demise. One might imagine that the basic structure of the building, its perimeter walls and floors would have been those least likely to be altered over time, while the external finish and the disposition and types of windows and doorways must have been remodeled quite frequently.

The first photograph (fig. 41) was taken from beneath the façades of the south side of the Markt at approximately 11:43, while the successive (fig. 43) approximately from the middle at 12:40, and the last (fig. 44) from a few steps to the right at 13:05. We know that Jacobus Hendricus Johan (Henri) de Louw (1851–1944), a Dutch photographer based in Delft and The Hague, took the first photograph. The photographers of the subsequent images remain unidentified.Henri de Louw was a notable Dutch photographer who worked in Delft and The Hague, mainly as a portrait photographer while also capturing topographical images of cities. He was the son of a photographer and began his career in The Hague before working with and eventually marrying the daughter of photographer Emma Kirchner. After a short partnership with Kirchner, he set up his own studio. He moved his business between Delft and The Hague during his career and trained several pupils. His marriage ended in 1901, and he ceased working as a photographer after 1928. He died in The Hague in 1944. His brother was also a photographer.

Despite their evident similarities, these photographs were likely taken in different days if not different seasons. The foliage of the four trees that flank the Nieuwe Kerk in the 12:40 and 13:05 photographs is notably more dense than that of the 11:43 photograph. On the other hand, the 12:40 and 13:05 photographs bear closer resemblance to one another. For example, the patterns created by the patches of background sky that peep through the foliage of the left-hand trees are unusually similar. Upon closer inspection, the object resembling a broom leaning against the façade of the left-hand perimeter of the building to the immediate left of Mechelen in the 12:40 photograph seems to be present in the 13:05 photograph as well. Moreover, the perspectives tell us that the two were taken from close to the same spot on the immense Markt. This raises the possibility that they were taken on the same day, potentially by the same photographer, possibly even De Louw..

The 11:43 image shows a capped man (with a hand-held satchel and a cane?) standing in line with the left-hand flank of the Nieuwe Kerk and a second, slightly blurred male figure who partially obscures the lower part of Mechelen's façade. The 12:40 photograph features a standing male figure similar to the previous one, this time directly under the entrance to the Nieuwe Kerk, and a second very blurred male figure to the left left, closer to the viewer. The 13:05 image shows the Markt completely empty.

Given the front-facing static posture and the length of exposure time of period photographic equipment, it seems very likely that the focused figures were instructed to stand still for the time required to expose them correctly. Early cameras had a very slow shutter speed, meaning that the shutter remained open exposing the plate to light for a longer period of time. Any movement caused blurriness. Although early daguerreotype images required an exposure of around twenty minutes, by the early 1840s it had been reduced to about twenty seconds. Even so, photography subjects needed to remain completely still for long periods of time for the image to come out crisp and not blurred by their movement.

Despite its blurred figure, the 11:43 photograph provides the widest view of Mechelen's façade (fig. 41), since it was taken from a less acute angle than the successive two, closer to the south side of the Markt. We can clearly see that the building has two floors and a loft, as in the Last (fig. 32) and Bos (fig. 34) prints.

The 12:40 photograph allows us to make out the façade's features with the greatest clarity (fig. 43). The ground floor features a series of four tightly fit openings, in succession from left to right: a window, a door, a second window and a second door. The upper partitions of the windows seem to be fitted with shutters, while the lower partitions are fitted with two elongated lites, just like those of the ground-floor windows of the second building to the right of Mechelen. The structure of the doors are more difficult to make out although both are topped with a window with a roughly square frame.

The first two windows of the upper story are fitted with shutters, divided in two sections by rails. In the 12:40 and 13:05 photographs the lower partitions of the shutters are open while in the earlier 11:43 image they are closed. The third window is composed of six lites, the upper two apparently fixed.

Similar to both the Last and Bos prints, a hip roof encloses a loft that is fitted with a central windowed dormer that projects vertically beyond the plane of the pitched roof. Such dormers were used to increase usable space of the loft and provide light to attic-level bedrooms. Although the top of Mechelen's roof it seems to rise slightly higher than that of the building to the right, perspective orthogonals show that it is slightly lower.

Differently from the pre-1885 photographs, the Last print shows a central door flanked by two large windows on the ground floor while only two windows appear on the upper floor. Despite the fact that the Bos print is far less defined than the photographs, it is in agreement with the number and positions of the façade's openings.

Created by Timothy De Paepe <https://3dtheater.wordpress.com/>

Photograph before 1885: 11:43 o'clock

Click here for a high-resolution downloadable image.

before 1885

Jacobus Hendricus Johan (Henri) de Louw

Photograph on paper

before 1885

Jacobus Hendricus Johan (Henri) de Louw

Photograph on paper

Before 1885: 12:40 o'clock

before 1885

Photograph on paper

before 1885

Photograph on paper

Before 1885: 13:05 o'clock

before 1885

Photograph on paper

Collection of Peter Jochems

before 1885

Photograph on paper

Collection of Peter Jochems

Before 1885

Private collection of Peter Jochems

Private collection of Peter Jochems

Second half of the 18th century

Jacob Elias la Fargue

Second half of the 18th century

Drawing in pen and watercolor, brush in colors, 25.2 × 34.9 cm.

Jacob Elias la Fargue

Second half of the 18th century

Drawing in pen and watercolor, brush in colors, 25.2 × 34.9 cm.

A mid-eighteenth-century watercolor (fig. 49) by the Dutch painter Jacob Elias la Fargue (1735–1778) offers a somewhat fanciful view of Voldersgracht as seen from Cameretten, a small square in the center of the city of Delft. The buildings beneath the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk are bordered by the Voldersgracht canal at the rear and by the Markt at the front, the latter not visible in the scene. In the distance, two arched bridges are visible (fig. 49), presumably those that still allow the Oude Manhuissteeg and the Bonte Ossteeg to span the canal, connecting the Markt and the Voldersgracht.

The bridge on the left-hand side spans the Oude Manhuissteeg, which Vermeer must have crossed many times. Although fanciful in execution, La Fargue's painting nonetheless furnishes an idea of what the Oudemanhuisbrug looked like before it was lowered in 1885, following the blueprint made by the architect C.J. de Bruijn Kops (fig. 54 & 55).

Photograph courtesy Tatiana Golovko

a. Oudemanhuisbrug (Oude Manhuissteeg bridge)

b. Bonte Ossteeg

Photograph courtesy Tatiana Golovko

1885

Click here to download a high-resolution digital image of the blueprint proposed in 1885 for the widening of the Oude Manhuissteeg alley with a new bridge over the Voldersgracht.

"In May 1885, the city architect CJ de Bruijn Kops made a plan (fig. 48 & 49) for a wider and lower bridge over the Voldersgracht, as well as an expanded alley to facilitate traffic to and from the Markt. Previously, "an advertisement in the Delftsche Courant of 10 June 1885 called on candidates for the demolition of the Mechelen house and the construction of the new bridge."George Buzing and Gerrit Verhoeven, Gerrit. "Markt 54–56 (demolished)," Achter de gevels van Delft. Accessed November 6, 2023However, at the request of the municipal council, De Bruijn Kops had already attempted to acquire the house east of the Oude Manhuissteeg so that it could be demolished to make way for the wider venue. He came to believe that the building was not so dilapidated after all and, more importantly, the three owners would have had to be bought out before it could be pulled down.George Buzing and Gerrit Verhoeven, Gerrit. "Markt 54–56 (demolished)," Achter de gevels van Delft. Accessed November 6, 2023Thus, it was decided that Mechelen would be demolished.

The Kops plans allow us to determine the exact position and dimensions of Mechelen with respect to the surrounding constructions. According to the blueprint (fig. 54) Mechelen was 6.75 meters (c. 22 feet) wide on the Markt-side and 8 meters (c. 26 feet) at the Voldersgracht. Conversely, the Oude Manhuissteeg was 1.80 meters (c. 6 feet) on the Markt-side and 2.20 meters (c. 7 feet) at the Voldersgracht.

When these dimensions are scaled to the current site, the combined lengths of Mechelen and the Oude Manhuissteeg correspond precisely to the space once occupied by the now-demolished Mechelen(fig. 53).

Draftsman: CJ de Bruyn Kops 1829–1891 (architect; draftsman)

1885

Blueprint, pen in ink, carrier dimensions: 58 × 85 cm. / overall dimensions: 48.5 x 83 cm.

Construction drawing with the existing situation and the changed state of the situation and cross-section, scale 1: 100.

Draftsman: CJ de Bruyn Kops 1829–1891 (architect; draftsman)

1885

Blueprint, pen in ink, carrier dimensions: 58 × 85 cm. / overall dimensions: 48.5 x 83 cm.

Construction drawing with the existing situation and the changed state of the situation and cross-section, scale 1: 100.

Comparative hypothesis for Mechelen

1. 1625–1626 (Gillis van Scheyndel)

2. c. 1730 (Leonard Schenk)

3. 1849 (Anthony Last)

4. pre-1885 photograph