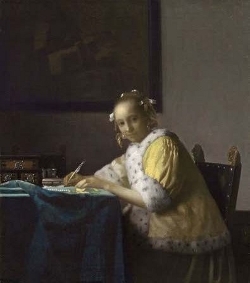

No. 1. "A young lady weighing gold, in a box, by J. van der Meer of Delft, extraordinarily artful and vigorously painted" 155-0.

(Een Juffrouw di goud weegt, in een kasje J. vander Meer van Delft, extraordinaer Konstig en kratig geschildert)

The description of the painting No. 1 of the Dissius auction catalog is unanimously believed to correspond to the Woman Holding a Balance of the National Gallery (fig. 1). Although we know nothing about the box in which the painting was kept, we do know that in the inventory of Jacob Dissius's house, there were three "Vermeer's in boxes" in the front room.

Particularly precious paintings (or nudes, for reasons of decorum) may have been protected from dust in such a manner (fig. 2). Curtains were commonly used for the same purpose and were often represented in Dutch interior paintings, including those by Vermeer (Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window). Cornelis Daemen Rietwijck, Vermeer's former neighbor on the Voldersgracht (Voldersgracht number 20, just west of the Oude Mannenhuis [Old Men's House]), is also known to have kept a painting of the head of Christ and a figure of Mary in such small boxes. Vermeer biographer John Michael Montias (Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History, 1989) suggested that the artist first learned to read and write at a nearby school and then attended the small academy run by Rietwijck.

Another supposition is that the painting was originally a piece of a so-called "peep-box" or "peep-show," an unusual device that served to create the most complete sense of visual illusion possible. Carl Fabritius, Vermeer's contemporary, was known to have constructed such a device. One exemplar by Samuel van Hoogstraten is conserved in a near-perfect state in the London National Gallery.

Fig.1Woman Holding a Balance

Fig.1Woman Holding a Balance c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 42.5 x 38 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C

Frans van Mieris

1667

Oil on panel, 27 x 22 cm.

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden

In any case, painting No. 1 fetched a very high price—155 guilders—considering its relatively modest dimensions. The buyer was Isaac Rooleeuw, a Mennonite and silk merchant (c. 1650–1710), who also purchased The Milkmaid, now in the Rijksmuseum. Rooleeuw must have known very well exactly which Vermeer paintings he wished to acquire, given that he was willing to pay such disproportionate prices for the pair. For five years, the two works hung side by side in his home in Amsterdam, until Rooleeuw went bankrupt and the paintings were sold. The Woman Holding a Balance remained in private hands in Amsterdam for another century, until shortly after 1800, when she left the Netherlands and eventually, in 1942, found her way via a circuitous route through Europe to Washington’s National Gallery of Art.

The Woman Holding a Balance is the only painting by Vermeer that can be traced in an unbroken line from the 17th century.

No. 2. "A maid pouring out milk, extremely well done, by ditto" 175-0.

(Een Meyd di Melk uytgiet, uytnemende goet van dito)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1658–1661

Oil on canvas, 45.5 x 41 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The description of painting No. 2 is unanimously recognized as the Milkmaid (fig. 3), now in the Rijksmuseum. The painting commanded an exceptionally high price (175 guilders) compared to other works of similar dimensions. It was also purchased by the same buyer of Woman Holding a Balance, (No.1), Isaac Rooleeuw. Unfortunately, Rooleeuw was able to savor his two masterpieces only briefly, as both paintings were sold by foreclosure after his bankruptcy, five years after the Dissius auction took place.

No. 3 The portrait of Vermeer in a room with various accessories, uncommonly beautiful painted by him" 45-0.

Portrait van Vermeer in een kamer met verscheyde bywerk ongemeen fraai van hem geschildert.

Although the well-known The Art of Painting in Vienna (fig. 4) might conceivably fit the brief description of painting No. 3, most scholars reject this hypothesis based on the low price paid for the picture. The "portrait of Vermeer in a room" was sold for only 45 guilders, while works of much smaller dimensions such as the Milkmaid and Woman Holding a Balance fetched 175 guilders and 155 guilders, respectively.

It is unlikely that such a richly complex work as The Art of Painting was not appreciated by the same public that was competent enough to distinguish the Milkmaid from lesser works of approximately the same size. Its ingenious perspective accuracy alone, one of the most esteemed aspects of Vermeer's and Dutch painting, would have surely attracted greater interest.

In fact, Vermeer's art was once noted by a contemporary connoisseur precisely for the artist's skill in perspective. If we consider the painting's perspective, extraordinary illusionistic quality, and notable pictorial technique, it seems impossible that The Art of Painting could have been underestimated, and even penalized, to such a degree.

The name of a Dutch painter has been invoked twice regarding the lost picture; Michiel van Musscher (1645–1705). In fact, three of his paintings could conceivably relate to the description of the lost picture by Vermeer: Van Musscher's The Artist’s Studio (fig. 5) in a private collection, Portrait of an Artist in His Studio (fig. 6) in the Bass Museum, Miami Beach, Florida, and Portrait of the Artist in His Studio in the Leiden Collection in New York (fig. 7).

Despite its conventional execution, the first picture (fig. 5) clearly reveals Van Musscher's attempt to capitalize on the ambitious composition of Vermeer's grandiose Art of Painting. It is tempting to believe that Van Musscher might have reworked the now-lost painting, but its composition is too similar to that of Art of Painting. The lighting of the work in the Bass Museum is very weak by Vermeer's standards. The Leiden Collection piece is technically the most refined of the three, but its cluttered composition and almost frontal lighting suggest a work derived independently from any work by Vermeer.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1668

Oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Michiel van Musscher

1670

Oil on canvas, 77 x 65.3 cm.

Private collection

Michiel van Musscher

Bass Museum

Miami Beach, Florida

Michiel van Musscher

1673

Oil on panel, 37.4 x 28.6 cm.

Leiden Collection, New York

No. 4 "A young lady playing a guitar, very good by the same" 70-0.

(Een speelende Juffrow op een Guiteer, heel goet van den zelve.)

Even though the specific use of the word "guitar" clearly indicates The Guitar Player (fig. 8) of the Iveagh Bequest in London, it's not entirely out of the question that Woman with a Lute (fig. 9) in the Metropolitan might also be considered as the painting listed as No. 4. The nomenclature used in inventory descriptions is approximate, although Walter Liedtke opines "it seems much less likely that in the late seventeenth century a lute or cittern would be described as a guitar than vice versa. On the other hand, one would expect a late work by Vermeer, not the Woman with a Lute, to have remained unsold in his studio." The substantial price given to the painting seems more than justified by the London picture's exceptional luminosity.

Unfortunately, the Woman with a Lute is in such a poor state of conservation that its aesthetic value is seriously compromised.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1673

Oil on canvas, 53 x 46.3 cm.

Iveagh Bequest, London

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 51.4 x 45.7 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

No.5 "In which a gentleman is washing his hands

in a perspectival room with figures, artful and rare, by ditto" 95-0.

(Portrait van Vermeer in een kamer met verscheyde bywerk ongemeen fraai van hem geschildert)

Samuel van Hoogstraten

Between 1654 and 1662

Oil on canvas, 103 x 70 cm.

Musée du Louvre, Paris

The most surprising catalogue description in the Dissius auction catalogue refers to a now-lost composition, "In which a gentleman is washing his hands in a perspectival room with figures, artful and rare..." The picture fetched 95 guilders, making it one of the highest priced works of the auction.

The "perspectival room" had been experimented with at other times by Vermeer in the early A Maid Asleep and the later The Love Letter. This pictorial device, also called doorkijkje, was practiced by other Dutch genre painters such as Pieter de Hooch (Couple with a Parrot; Fig. 10) and Samuel van Hoogstraten (The Slippers; Fig. 10). Curiously, Vermeer's Love Letter (Fig. 12), De Hooch's Couple with a Parrot and Van Hoogstraten's Slippers all have a broom leaning against the foreground doorway in common.

As Vermeer expert Albert Blankert has pointed out, no other Dutch genre painting features a gentleman washing his hands. The hand-washing theme was most likely an allegory for the cleansing of one's soul.

Pieter de Hooch

1668

Oil on canvas, 73 x 62 cm.

Wallfar-Richartz-Museum, Cologne

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1667–1670

Oil on canvas, 44 x 38.5.cm.

Rijksmuseum , Amsterdam

No. 6 "A young lady playing the clavicen in a room, with a listening gentleman, by the same" 80-0.

(Een speelende Juffrow op een Guiteer, heel goet van den zelve)

Art historians generally believe that painting No. 6 of the Dissius auction sales catalogue refers to either Vermeer's Music Lesson (fig. 13) or The Concert (fig. 14).Walter Liedtke beleives it is almost certainly The Music Lesson.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 73.3 x 64.5 cm.

The Royal Collection, The Windsor Castle

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1663–1666

Oil on canvas, 72.5 x 64.7 cm.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

No. 7 "A young lady who is being brought a letter by a maid, by ditto" 70-0.

(Daer een Seigneur zyn handen wast, in een doorsiende Kamer, met beelden, konstig en raer van dito)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1666–1668

Oil on canvas, 90.2 x 78.7 cm.

Frick Collection, New York

As most other Vermeer scholars, the late Dutch Vermeer specialist Albert Blankert believes that the description of painting No. 7 applies more precisely to the larger Mistress and her Maid (fig. 15) rather than to the Love Letter, due to its relatively high price.

Walter Liedtke noted this description better suits the Frick picture than The Love Letter in Amsterdam...since the cataloger usually referred to motifs such as musical instruments and "see-through room' (lot 5, now lost). Ownership of the Mistress and Maid as well as A Lady Writing would also be more consistent with our tentative impression of [Vermeer's principal patron] Van Ruijven's taste, which appears to have favored evocative understatement (and light effects) over prosaic narrative."

In 2012, the Dutch art historian Franz Grizenhout confidently identified the name of another buyer at the Dissius auction. "A well-documented case can now be added to our scarce knowledge on the position of Vermeer in early 18th-century collections. We already knew that Mistress and Maid (Frick Collection, New York) was sold at an anonymous auction in 1738 to someone called Oortman. As it turns out, this was Hendrik Oortman (1696-1748), who bought the picture by Vermeer in 1738 at the auction of paintings that belonged to his father, Jacob Oortman (1661-1738), a pistol and gun maker and one of the wealthiest men in Amsterdam at the time. Jacob Oortman possessed some 80 paintings, a dozen of which were probably bought at the Dissius auction of 1696, along with the Vermeer. They were kept in his house on Singel, Amsterdam. Thanks to the inventory of Jacob Oortman’s belongings made up after his death, we can document the disposition of these paintings in the house fairly accurately. Apart from a nice collection of porcelain, Oortman owned several interesting pictures, including Pieter de Hooch’s famous Mother’s Duty, now in the Rijksmuseum."Franz Grizenhout, "Een schrijfstertje van Vermeer. Jacob Oortman en de Dissiusveiling van 1696," Oud Holland Jaargang/Volume 123, no. 1 (2010).

His wife was Petronella Oortman (1656–1716), who, between 1686 and 1710, curated the best-known dollhouse of the time, decorating it with expensive materials and miniatures. It is so accurately constructed that it provides a unique insight into the domestic life and aspirations of the upper class during the 17th century, offering clues about the preferences, tastes, and aspirations of the women and families who owned and curated these miniature collections.

No. 8; "A drunken sleeping maid at a table, by the same" 62-0.

(Een dronke slapende Meyd aen een Tafel, van den zelven)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1656–1657

Oil on canvas, 87.6 x 76.5 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Few doubt that painting No. 8 of the Dissius auction catalogue applies to Vermeer's A Maid Asleep (fig. 16).

No. 9 - "A merry company in a room, vigorous and good, by ditto." 73-0.

(Een vrolyk geselschap in een Kamer, kragtig en goet van dito)

Most scholars agree that the description of painting No. 9 best suits the Girl with a Wine Glass in the Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum (fig. 17). However, there may have once existed other paintings by Vermeer that could match the catalogue description.

Walter Liedtke noted that this description "would suit The Concert (fig. 18) equally well or better, especially when one considers how specifically the cataloguer describes the figures in other entries, and the fact that the title, 'Merry Company', was commonly applied in seventeenth-century inventories to paintings of music-making ensembles consisting of three figures or more. The sale's cataloguer describes what each figure is doing in every picture by Vermeer, including one or two figures, whereas the term 'merry company' was commonly applied throughout the century to scenes of three or more figures making music or otherwise socializing. If the Braunschweig painting was in the Dissius sale, it seems likely that the cataloguer would have described the man's offer of wine or the woman's expression (quite as he noted 'een laggent Meysje' [a laughing girl] Officer and Laughing Girl), or he would have chosen words like those employed for lot 23, 'Een geselschap van drie Persoonen van Gerard Terburgh' (A company of Three Persons by Gerard ter Borch)."

…Fig. 17 The Girl with a Wine Glass

…Fig. 17 The Girl with a Wine Glass Johannes Vermeer

c. 1659–1662

Oil on canvas, 78 x 67 cm.

Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Brunswick

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1663–1666

Oil on canvas, 72.5 x 64.7 cm.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

No. 10 "A gentleman and a young lady making music in a room, by the same" 81-0.

(Een Musiceerende Monsr. en Juffr. in een Kamer, van den zlve)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1658–1661

Oil on canvas, 39.3 x 44.4 cm.

Frick Collection, New York

Description No. 10 may refer to either Girl Interrupted at Her Music (fig. 19) or The Music Lesson. One argument against Girl Interrupted at Her Music is that the painting fetched a rather high price: 81 guilders. Even though the painting is now in a very poor state of conservation, neither its reduced dimensions nor remaining visible qualities seem to justify such an elevated price. On the other hand, The Music Lesson is one of Vermeer's most complex works. The Concert also represents a gentleman and a young lady making music. However, the description does not take into account a second young woman who is beating time and singing. Other paintings by Vermeer may have once existed that could match the catalogue description.

No. 11 "A soldier with a laughing girl, very beautiful, by ditto" 44-10.

(Een Soldaet met een laggent Meysje, zeer fraie van dito)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1655–1660

Oil on canvas, 50.5 x 46 cm.

Frick Collection, New York

Art historians are concorde in attributing Vermeer's Officer and Laughing Girl (fig. 20) as painting No. 11.

No. 12 "A young lady doing needlework, by the same" 28-0.

(Een juffertje dat speldewerkt, van dem zelven)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1669–1671

Oil on canvas on panel, 24.5 x 21 cm.

Musée du Louvre, Paris

The description of painting No. 12 in the Dissius auction catalog almost certainly refers to The Lacemaker (fig. 21) in the Louvre. Among those paintings by Vermeer that are surely identifiable in the Dissius catalog, The Lacemaker fetched a relatively high price in relation to its size. Only Woman Holding a Balance and The Milkmaid were bought for higher relative prices.

No. 31 "The Town of Delft in perspective, to be seen from the south, by J. van der Meer of Delft" 200-0.

(De Stad. Delft in perspectief, te sien van Zuyd-zy, door J. vander Meer van Delft)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1660–1663

Oil on canvas, 98.5 x 117.5 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

Art historians agree that painting No. 31 fits Vermeer's monumental View of Delft (fig. 22). Although View of Delft fetched the highest price (200 guilders) of the Dissius auction, it was also by far the largest canvas. It is surprising to note that Woman Holding a Balance (catalogue No. 1, at 155 guilders) and The Milkmaid (catalogue No. 2, at 175 guilders) were both paid almost as much even though they are far smaller.

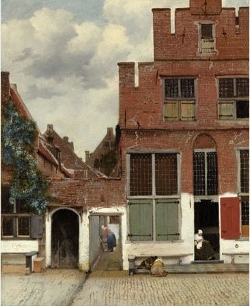

No. 32 "A view of a house standing in Delft, by the same" 72-10.

(Een Geschit van een Huys staende in Delft, door denzelven)

No. 33 "A view of some house, by ditto" 48-0.

(Een Geschit van eenige Huysen van dito)

Scholars generally hold that the description of No. 32 in the Little Street (fig. 23) now housed in the Rijksmuseum, although strictly speaking, there is no reason it could not fit No. 33. Whatever the case, the other view of houses no longer exists.

Thorè-Bürger, the French connoisseur who is generally credited for having rediscovered Vermeer in the mid-18th century, attributed various landscapes and cityscapes to the Delft master that were successively removed from the artist's oeuvre. Thorè had in his personal art collection more than one landscape which he believed to be authentic. However, they were later proven to be by the hands of minor artists such as Jacob Vrel or Dirk Van de Laan (fig. 24), the latter of which was a Dutch painter who was clearly influenced by Vermeer's pointillist application of paint and intimist qualities.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1657–1661

Oil on canvas, 54.3 x 44 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Dirk Jan van der Laan

1792

(whereabouts unknown

No. 35 "A writing young lady, very good, by the same" 63-0.

(Een Schyuvende Juffrouw heel goet van denzelven)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1667

Oil on canvas, 45 x 39.9 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C

The description of painting No. 35 is usually considered to refer to A Lady Writing (fig. 25) in the National Gallery in Washington. However, there may have once been another painting or paintings by Vermeer that could match the catalogue description. Walter Liedtke noted that "Jacob Dissius's father-in-law, Pieter van Ruijven, had acquired comparable paintings by Vermeer such as the Woman with a Pearl Necklace and Woman Holding a Balance, so there can be little doubt that he also purchased A Lady Writing directly from the artist"

No. 36 "A lady adorning herself, very beautiful, by ditto" 30-0.

(Een Paleerende dito, seer fraye van dito)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 55 x 45 cm.

Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

The description of painting No. 36 matches the Woman with a Pearl Necklace (fig. 26) in Berlin, although there may have once existed another painting(s) by Vermeer that could mathe catalogue description.

No. 37 "A lady playing the clavicen, by ditto" 42-10.

(Een Speelende Juffrouw op de Clavecimbaerl van dito)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1674

Oil on canvas, 51.7 x 45.2 cm.

National Gallery, London

The description of painting No. 37 of the Dissius auction catalog could conceivably fit various pictures by Vermeer, including A Lady Standing at a Virginal (fig. 27), A Lady Seated at a Virginal, and the recently reattributed A Young Woman Seated at the Virginals, in the Leiden Collection in New York.

However, given the relatively high price achieved by the work in question, the Leiden piece should be discarded, considering its evident inferior quality and smaller dimensions.

According to Walter Liedtke, "even if the London paintings were separated at an early date (about a decade after they were painted) this hardly militates against the possibility that they were painted as a pair. In the period about 1672, when Vermeer evidently sold very little, he may have been more than willing to part with the works separately."

No. 38 "A tronie in antique dress, uncommonly artful, by the same" 36-0.

(Een Tronie in Antique Kelderen, ongemeen konstig)

No.39 "Another ditto by Vermeer" 17-0.

(Nog een dito van Vermeer)

No. 40 "A pendant by the same" 17-0.

(Een weerge van denzelven)

The term tronie, which is derived from the French "trogue," refers to "heads" or "faces" in paintings that had been popularized by Rembrandt and his followers. Even though a tronie represents a bust-length, single figure and is usually painted from life, it is not a portrait in the 17th-century sense of the word. In contemporary usage, tronie might cover any picture of an unidentified sitter, but in modern art-historical usage, it is typically restricted to figures who do not appear to have been intended to be identifiable. The tronie provided the artist with an opportunity to demonstrate his ability in rendering fine materials, exotic garments, or characteristic facial types that struck him as unusual. The artist wearing exotic headgear, the dashing soldier, or the "Turkish archer" were favorite tronies. Vermeer's Girl with a Red Hat (fig. 28) Study of a Young Woman (fig. 29) and Girl with a Pearl Earring (fig. 30) would all be considered tronies, not portraits. Tronien were probably sold on spec. The tronie, then, "with its anonymous models doing and meaning next to nothing, was perfect for collectors who wanted an affordable proof of the technical mastery of a given painter."

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1665–1667

Oil on panel, 23.2 x 18.1 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1665–1667

Oil on canvas, 44.5 x 40 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1665—1667

Oil on canvas, 46.5 x 40 cm.

Mauritshuis, The Hague

Painting No. 38 has often been thought to refer to Vermeer's iconic Girl with a Pearl Earring, currently in the Mauritshuis. Although its price was not as high as one might expect—only 36 guilders—in reality, tronies normally did not command high prices. Even a Rembrandt tronie in the same sale (No. 45) fetched only 7 guilders and 5 stuivers. Johan Larson, a Hague/London sculptor, had in his collection a Vermeer tronie valued at only 10 guilders. However, Vermeer's chief biographer, John Montias, believes that the Larson tronie was most likely the much smaller Girl with a Red Hat. The Study of a Young Woman was sold with painting No. 38 for less than half the price of No. 39.

It should be remembered that Vermeer's contemporaries sometimes valued paintings differently than we do. For example, Vermeer's large Allegory of Faith in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which is today considered coldly distant in its classicism, was sold for 400 guilders just three years after the magnificent View of Delft was sold for 200 guilders. In the same auction, The Milkmaid was sold for 175 guilders, while The Music Lesson, now considered one of Vermeer's highest artistic and technical achievements, was sold for less than half that price—80 guilders.

It is possible that the Girl with a Flute and Girl in a Red Hat refer to the two pendant pictures in list number 40, but we have no idea how many tronies Vermeer painted.