M. LEBRUN, Peintre, Membre des Académies de Valence, de Florence, de Gènes, et de plusieurs Societés savantes et littéraires; Pensionnaire du Musée Napoleon, auteur de la Galerie des Peintres flamands, hollandais et allemands.

Early Life and Career

The French art dealer Jean-Baptiste Pierre Le Brun (1748–1813) was probably the most gifted connoisseur in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century France. In various publications he wrote about artistic education and artists, predominantly about the painters of the Écoles du Nord (Northern schools).. Between 1792 and 1796 he published his masterpiece: a comprehensive survey of painters of the Northern school called Galerie des peintres flamands, hollandais et allemands.

Le Brun was born in 1748 in Paris. He was the son of painter and art dealer Pierre Le Brun (c. 1700–1771), and grandnephew of the famous Charles Le Brun (1619–1690), premier peintre du Roi (Louis XIV). While training as a painter, the young Le Brun was more or less obligated to take over his father's art business when he died in 1771.2 Although Le Brun was not a great artist, no more than his father, he always regretted having been forced to give up his painting career prematurely. As is clear from his personal introduction cited above, he would always consider himself first and foremost a painter .

Like his father, Le Brun mainly sold paintings, drawings and graphic work.3 Like other dealers, the painters of the Northern school were his primary supply. Le Brun grew up with in the midst of his father's art dealings.4 According to Fabienne Camus, the young Le Brun regularly accompanied his father on business trips to the North, which may have kindled his affinity and great familiarity with the art of the Northern school.5

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Le Brun

1795

Oil on canvas, 131 x 99 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Le Brun's innovations in trading art

The art trade was always Le Brun's core activity. Like his famous predecessor Edme-François Gersaint (1694–1750), Le Brun was innovative in many respects. In their publications Neil DeMarchi and Hans van Miegroet formulated certain innovations, which have been of great influence for the development of the art trade.

First, in order to maximize profits, Le Brun continually optimized the operations of his auctions.6 Second, he considered art as an investment. Its relatively stable value, which had been recognized previously, was confirmed and expressed in auction catalogues which made mention of earlier results. This was another one of Le Brun's novelties. He encouraged his clients to purchase works of art arguing that they could enjoy them without having to fear value decrease or unsaleability.

Third, Le Brun contributed to the development of international art trade. While the European trade thrived primarily on a social network of aristocrats and art agents, in the first half of the eighteenth century Gersaint more or less introduced Dutch painting to the French market.7 While Gersaint acquired most of his stock in the Netherlands, Le Brun took the next significant step forward by not only traveling farther and more frequently, but also selling on an international scale.8 In the eighteenth century, the Northern painters comprised a major share of the paintings on the French market. However, few painters were known individually. As a result, the same familiar names were repeatedly seen at auctions. On one hand Le Brun tried to shift the focus away from names toward artistic and aesthetic quality, on the other he explored the Dutch art market, attempting to discover hitherto new and lesser known masters.9

Le Brun's Marriage with Elisabeth Vigée

Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun

1782

Oil on canvas, 97.8 x 70.5 cm.

National Gallery, London

In 1775, Le Brun married the talented painter Marie Louise-Elisabeth Vigée (1755–1842), who would later paint portraits of many of the nobility of the day and became so famous that she was invited in 1779 to the royal residence at Versailles Palace to paint a portrait of Marie Antoinette. The matrimony between the promising young painter and the well-established art dealer must have presented significant opportunities for professional advancement for both. Being agile in public affairs, Le Brun was soon able to conjugate his new contacts with upper-class amateurs and collectionneurs—which he owed in part to his marriage—with his own expertise and solid commercial network. This activity centered around Hôtel de Lubert, his private house and gallery.. 10 11

Without doubt, in this period Le Brun had become one of the most respected connoisseurs of the time.13 However, the Le Brun's marriage would prove to be a deception, and in her Souvenirs, published in1835 and 1837, Vigée would speak out against her late husband.12 The public perception of Le Brun in the nineteenth century was at least partially rooted in these memoirs.

Le Brun During the Révolution

At the outset of the Révolution, Vigée, who was an outspoken royaliste, fled to Italy with her young daughter Jeanne-Julie-Louise. Le Brun remained in Paris quickly accustoming himself to the changing circumstances. Out of political precaution he distanced himself from danger by divorcing Vigée.14 Nonetheless, he published a defense of her royaliste conduct in a twenty-two-page pamphlet, and succeeded in having her name removed from the list of counter-revolutionary émigrés.

Le Brun's masterpiece, the Galerie des peintres flamands, hollandais et allemands was published between 1792 and 1796. Its realization required many years and must have begun well before the Révolution. In the first volume, probably written before 1789, Le Brun clearly declared himself a royalist. In the second volume, he shifted political allegiance and embraced an outspoken revolutionary rhetoric. It was, perhaps, typical for the day that in the first volume he left his ode to Louis XIV Quatorze intact.15

After losing a great part of his aristocratic clientele, Le Brun set out to broaden his range of activity. As a respected expert, he became involved in the realization of the Muséum National, which would later become the Musée Napoleon. Le Brun was in charge with selecting and describing the art works in the museum that had previously belonged to members of the nobility who had either fled France or been condemned by law. In addition, Le Brun had an important role in the assessment and restoration of damaged paintings and expressed his ideas in regard to how the works of art of the Muséum's new collection should be exhibited.16 He suggested that artworks be arranged by geographical schools, similar to what he had done for the first time in the Galerie, of which he had supplied several copies to the Administration du Musée Central des Arts.17

While working at the Muséum Nationale, Le Brun published a number of theoretical works,18 championing Dutch and Flemish genre painting in assorted essays.19 In 1794, he wrote an interesting article regarding the advancement of the fine arts: Essai sur les moyens d'encourager la peinture, la sculpture, l'architecture et la gravure. Moreover, the extensive sales catalogues of his art dealings offered opportunities to engage in theoretical discourses. However, Le Brun is primarily known today for his pièce de résistance: the Galerie.

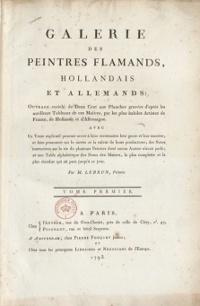

Galerie des peintres flamands, hollandais et hollandais

Galerie des peintres flamands,

hollandais et allemands

1792

Paris, France

The Galerie was Le Brun's magnum opus. In this extensive survey he presented his points of view with regard to the painters of the North. In the table alphabétique he gave an overview of all 1350 Flemish, Dutch and German painters known to him at that moment. A selection of the most estimable artists 157 works was discussed in the three volumes.20 The Galerie was published between 1792 and 1796 in Paris and Amsterdam, but was sold in Brussels, London, Vienna, Berlin and Florence as well. In Amsterdam it was available at Pieter Fouquet jr's, an art dealer and one of Le Brun's regular local business partners.21

In the Discours préliminaire Le Brun discussed the methods, structure and aims of the Galerie. His principal ambition was to inform amateurs and help them recognize the different painters of the Northern school and indicate which of these were worthy of a serious art collection. Importantly, he discriminated between painters who had been famous in their lifetimes, from painters who were discovered after their deaths and those gifted masters who remained obscure, but whose scarce works were esteemed only by their owners. In this respect he wrote most tellingly that he wished first and foremost to rediscover these forgotten talents and give them back a rightful place within the panorama of art history.22 In Rediscoveries in Art; Some aspects of taste, fashion and collecting in England and France the English art historian Francis Haskell discusses this important passage and focuses on the crucial notion of the découverte in particular. He considered Le Brun the first author to adopt this as a central tenet .23

Much as today, in Le Brun's days a good painting was required to bear the name of a famous artist. Consequentially, dishonest merchants attributed—and signed with their own hands—good paintings by unknown masters to famous names. Le Brun tried to break this fixation as well as the malicious practice of false attribution. For in his opinion a serious collector should not merely buy a famous name; he must first and foremost acquire a valid work of art. Therefore, it was necessary to become familiar not only with the painter's name, but the genre in which he worked, his personal style and particular talent. In the Galerie Le Brun attempted to formulate a théorie exacte et precise but emphasized that careful observation and comparison were necessary to identify stylistic similarities and differences.24 With its 201 engravings—a "scoop" according to Le Brun—the Galerie was an important resource regarding comparisons.25

The most distinctive structural aspect of the Galerie is in its arrangement of artists according to geographical schools. Instead of using the more conventional chronological or alphabetic order, Le Brun took a certain artistic school as a point of departure, and then discussed the principal masters and their pupils, as well as followers and influences.26 Aside from providing a description of the career, style and genre of these painters, Le Brun furnished the commercial value of their work. According to art historian Ivan Gaskell, Le Brun's method of interpreting the interaction between formal, stylistic and thematic aspects of artworks had a lasting impact on art history and museology.27

Contrary to the conventions of art patronage in seventeenth-century France, in the Low Countries the influence of the aristocracy and clergy on art production had been minimal. According to Le Brun, this explains why there were so few Dutch history painters and so many genre and landscape painters. In his great enthusiasm for Dutch painting he praised the school's color harmony, brushwork, meticulous detail and unsurpassed illusionism.28 In line with his personal predilections and judgments, a coherent group of painters can be distinguished within the framework of the Galerie. Not surprisingly, it was Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) who took the lead. Owing to the artist's fame and exceptional talent, Rembrandt had gathered many pupils. Le Brun listed no less than seventeen disciples, among whom were Ferdinand Bol, Govaert Flinck and above all Gerrit Dou.29 Interestingly, Le Brun considered Dou to be superior to his master and mentioned six of Dou's disciples, including the Leiden painter Gabriel Metsu.30 His esteem was such that his praise for Metsu was lyrical. In line with the Galerie's character, Le Brun associated the work of Metsu to that of many other painters and vice versa.

Within this context, for the first time in art history, the Delft painter Johannes Vermeer was mentioned—and even discussed—in Le brun's survey, whom he recognized as a true master:

C'est un très grand peintre dans la manière de Metzu. On les [les ouvrages] paye aussi cher que ceux de Gabriel Metzu.31

Le Brun expressed his appreciation for the unknown Vermeer in terms of the celebrated Gabriel Metsu. This first introduction of Vermeer was a very important découverte, as he announced in the introduction of the Galerie. The notion of découverte was essential to the Galerie; apart from Vermeer, Le Brun seems to have made quite a few.32

The Galerie not only had a theoretical basis, but rested on Le Brun's impressive connoisseurship and profound understanding of Dutch painting as well. Le Brun's innovative approach was an ambitious combination of several innovative tendencies. Although not the first in any, he was nonetheless the first to combine them into an illustrated survey of great breadth. According to the French art historian Gilberte Émile-Mâle (1913–2008), through the Galerie it was Le Brun who should be credited for having introduced Dutch painting to French amateurs and art professionals in the eighteenth century.33

Although the selection of 157 painters in the Galerie cannot be detached from Le Brun's commercial interests, the Frenchman seems to have acted upon a sincere desire for art historical justice. First in breaking the persistent focus on names. Second—and this is crucial to the Galerie—in introducing and positioning unknown masters and the disclosure of their oeuvres. Le Brun presented these unknown masters as découvertes.34

Summarizing Le Brun

Le Brun had always seen himself as a painter. This fact was crucial to the development of his connoisseurship, and it likewise conferred him a certain prestige. In 1792, Le Brun offered his services to the restoration commission of the Muséum Nationale. Le Brun projected himself as himself as eloquent and confident connoisseur. As he wrote himself: the "complete and accurate knowledge" gives us an impression of the extent in which he regarded himself judicious.35

In 1956, Gilberte Émile-Mâle, Le Brun's first biographer, defined him as the greatest connoisseur of his time; capable, conscientious and reliable. In an interesting article, also published in 1956, the French art historian Albert P. de Mirimonde (1897–1985) characterized Le Brun as a curious spirit with a sharp eye and an intuition for the rare and precious. As a result of his intensive traveling, these rare qualities were constantly evolving.36 In Rediscoveries in Art, Haskell wrote that Le Brun was, in fact, "the first connoisseur to break with the prevailing habit of trying to attribute as many pictures as possible to the great and established names and to insist instead on the value of rarity and unfamiliarity.37 38 Haskell considers Le Brun exemplary: "In his own person, he sums up so many of the influences that will be concerning us [in Rediscoveries in Art. red.]."39

Even so, Haskell mentions that Le Brun was himself probably guilty of engaging in the malicious practice of false attributions, which he condemned in the introduction of the Galerie. For instance, Haskell suspected that Le Brun allowed some of the landscapes that he had ordered from Georges Michel (1763–1863), "the most Dutch of French landscape artists," to pass as seventeenth-century originals. Besides, according to Haskell, Le Brun had initially planned to sell an Astronomer by the then unknown Vermeer as an unsigned work by the more celebrated Gabriel Metsu.

In her dissertation on Le Brun, Fabienne Camus supposed that Le Brun had to some extent influenced the prevailing aesthetic trends of his time and changed the general idea of painting.40 One thing is certain; as a painter, entrepreneur, connoisseur and theoretician, Le Brun possessed a rare and profound knowledge of Dutch painting.

† FOOTNOTES †

- Le Brun, Jean-Baptiste Pierre. Recueil de gravures au trait, à l'eau-forte, et ombrées d'après un choix de tableaux de toutes les écoles, recueillis dans un voyage fait en Espagne, au Midi de la France et en Italie, dans les années 1807 et 1808. Paris 1809, frontispice.

- Le Brun received his training from Jean Baptiste Deshayes, François Boucher (1703–1770) and Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806),

- And to a lesser extent sculpture, objets d'art and precious furniture.

- As a result of the high quality and ample availability the French art market in the second half of the eighteenth century developed significantly around the painters of the North. Dutch genre painters and fijnschilders were popular; amateurs appreciated the pleasant subject matter, use of color, superb finishing and small size.

- Le Brun, Jean-Baptiste Pierre. Galerie des peintres flamands, hollandais et allemands; Ouvrage enrichi de Deux Cent Une Planches gravées d'après les meilleurs Tableaux de ces Maîtres, par les plus habiles Artistes de France, de Hollande et d'Allemagne. Paris, Amsterdam 1792–1796. Volume 2: p. 79.

- De Marchi, Neil en Hans J. van Miegroet. ‘The rise of dealer-auctioneers. Information and transparency in markets for Netherlandish paintings.' In: Jonckheere, Koen en Anna Tummers, red. Art Market and connoisseurship in the Dutch Golden Age. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2008: p. 149–174

- Jonckheere, Koen J.A. Kunsthandel en diplomatie. De veiling van de schilderijenverzameling van Willem III (1713) en de rol van het diplomatieke netwerk in de Europese kunsthandel. Diss. Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2005. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2005.

- Therefore, in most European cities Le Brun had a regular business partner. For example, from the early 1770s, in Amsterdam he worked together with Pieter Fouquet jr. (1729–1800).

- Le Brun, Jean-Baptiste Pierre. Galerie des peintres flamands, hollandais et allemands; Ouvrage enrichi de Deux Cent Une Planches gravées d'après les meilleurs Tableaux de ces Maîtres, par les plus habiles Artistes de France, de Hollande et d'Allemagne. Parijs, Amsterdam 1792–1796. Volume 1: p. iii.

- Michel, Patrick. Le commerce du tableau à Paris dans la seconde moitié du XVIIIe siècle. Villeneuve d'Ascq: Septentrion, 2007: p. 87.

- By virtue of his familiarity with aristocratic spheres he was asked to make acquisitions for the royal cabinet. He was also garde des tableaux for the count of Artois and the duke of Orleans. His social abilities in aristocratic spheres became apparent through the acquisitions he was asked to make for the royal cabinet. He was also garde des tableaux for the count of Artois and the duke of Orleans. Émile-Mâle, Gilberte, ‘Jean-Baptiste Pierre Lebrun (1748–1813). Son rôle dans l'histoire de la restauration des tableaux du Louvre.' Mémoires de la Fédération des sociétés historiques et archéologiques de Paris et de l'Île-de-France. nr. 8 (1956): p. 372.

- Vigée-Le Brun, Louise-Elisabeth. Souvenirs de Madame Louise-Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun. Parijs 1835.

- During his professional life, Le Brun was a member of numerous commissions and academies in France and abroad. In his personal introduction from 1809, quoted above, we read for instance: Membre des Académies de Valence, de Florence, de Gènes, et de plusieurs Societés savantes et littéraires. Le Brun also mentions his function of Pensionnaire du Musée Napoleon. Émile-Mâle mentions Le Brun's membership of the Institut National de Naples.

- On the other hand, he defended her by giving her escape to Italy an artistic motivation. Émile-Mâle 1956: 389.

- When our opportunistic, pragmatic art dealer had the courage in 1792, it must have still been safe at that time. After all, Louis XVI ‘Seize' was still alive and La Terreur had not yet begun. Le Brun 1792–1796: deel 1, p. 18.

- Le Brun 1792–1796: volume 1, p. 18.

- Émile-Mâle 1956: 389.

- The publications Réflexions sur le Muséum national, Observations sur le Muséum national, and Quelques idées sur la disposition, l'arrangement et la décoration du Muséum national.

- "[…] comme si la peinture se bornait a peindre des héros, comme si Teniers, par exemple, n'était pas aussi immortel pour avoir peint l'intérieur d'une maison rustique que Sébastien […]" Journal de Paris, 17 September, 1798. Émile-Mâle 1956: 389.

- The history of the Galerie begins in 1777 with the first edition of a series of reproductions of famous Dutch and Flemish masters. Until 1790 in total twelve editions were published, each containing twelve engravings. In 1790 the separate print books were taken off the market, making room for the eventual extensive survey.

- Prigot, Aude, 'Une entreprise franco-hollandaise: la 'galerie des peintres flamands, hollandais et allemands' de Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Lebrun, 1792–1796.' In: G. Maës en J. Blanc, Échanges artistiques entre les anciens Pays-Bas et la France 1482–1814. Turnhout: Brepols, 2010: p. 215–222.

- Le Brun 1792–1796: deel 1, p. iii.

- Haskell, Francis, Rediscoveries in Art: Some Aspects of Taste, Fashion and Collecting in England and France. New York: Cornell University Press, 1976: p. 25.

- Le Brun 1792–1796: volume 1, p. x.

- However, according to Gilberte Émile-Mâle, Le Brun was not the first. Émile-Mâle 1956: 385.

- Le Brun 1792–12–1796: volume 1, p. iii.

- Gaskell, Ivan. "Tradesmen as scholars: Interdependencies in the Study and Exchange of Art." In: Mansfield, Elisabeth, red. Art History and its Institutions: Foundations of a Discipline. London: Routledge, 2002: p. 151.

- "L'école des Pays-Bas offre une foule de peintres d'un mérite supérieur. Quelle harmonie dans leur couleur! Quel charme dans leur pinceau! Quel fini précieux dans les détails meme les plus communs! Ils ont atteint dans leurs tableaux un degré de verité qu'il est presque impossible d'égaler, ou qu'il est du moins impossible de surpasser..." Le Brun 1792–1796: volume 1, p. ix.

- The French word disciple, as used by Le Brun, probably has a broader meaning here; in the descriptions concerned, Le Brun was more precise, using élèves (pupils) or suivants (followers).

- "Il a surpassé son maitre par un dessin correct, un costume moins bizarre et plus vrai, et par un fini gras et moëlleux qui semble inimitable." Le Brun 1792–1796: volume 1, p. ix.

- Le Brun 1792–1796: volume 2, p. 49.

- The most important painters Le Brun said to have rescued from oblivion were: Pieter Saenredam (1597–1665), Salomon de Bray (1597–1664), Simon de Vlieger (c. 1601–1653), (Nicolaes) Maes (1643–1693), (Jacob) Ochtervelt (1634–1682), Quiringh van Brekelenkam (c.1622-c.1669) and Joost van Geel (1631–1698).

- Émile-Mâle 1956: 387.

- "C'est sur ces derniers que je veux parler, c'est de ces hommes que, restés inconnus de leur vivant, et même après leur mort, ont besoin, pour reprendre la place qu'ils auraient du occuper parmi leurs rivaux et leurs contemporains, que leurs tableaux n'échappent point aux regards d'un curieux empressé de les chercher, et capable de les apprécier." Later on he added: "Plusieurs peintres ont été découverts ainsi […]." Le Brun 1792–1796: deel 1, p. iii.

- "Occupé depuis trente ans par goût plus que par interêt, à former des cabinets connus dans toute l'Europe, occupé du soin de faire restaurer des tableaux que le temps ou des accidents imprevus avaient détériores, initié surtout dans la connaissance entière et exacte de tous les différent maîtres des écoles célèbre…., j'ai peut-être, le droit de croire que je puis réunir mes efforts aux vôtres…" Émile-Mâle 1956: 391.

- "Il avait l'esprit curieux et l'oeuil fin, le goût du rare et le sens du précieux: ce ne sont point des qualités communes et comme il amait voir et voyager, il n'a cessé de les déveloper." Mirimonde, Albert P. de. ‘Les Opinions de M. Lebrun sur la peinture hollandaise.' Revue des Arts, nr. 6 (1956): p. 207.

- According to Haskell, the Galerie was "[…] designed to bring to light hitherto neglected artists such as Saenredam, and was specifically intended to replace name snobbery by snobbery of the unknown, which was to open up infinite possibilities for historians and collectors."

- Interestingly, Thoré's over-enthusiasm in reconstructing Vermeer's oeuvre seems perfectly in line with the prevailing habit among connoisseurs that Haskell rejects.

- Camus, Fabienne. Jean-Baptiste Pierre Le Brun: Peintre et marchand de tableaux. Diss. Université Paris IV-Sorbonne, 2000: p 218.

- Camus 2000: 218.