…my work, which I've done for a long time, was not pursued in order to gain the praise I now enjoy, but chiefly from a craving after knowledge, which I notice resides in me more than in most other men. And therewithal, whenever I found out anything remarkable, I have thought it my duty to put down my discovery on paper, so that all ingenious people might be informed thereof.

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (Letter of June 12, 1716)

Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek was born in Delft on October 24, 1632, died there on August 26, 1723. His parents, Philippus Thonisz. van Leeuwenhoek and Margaretha Jacobsdr. Bel van den Bergh, were affluent citizens. His grandparents and great-grandparents were brewers in Delft. Leeuwenhoek was baptized on

November 4, 1632, in the Nieuwe Kerk (New Chruch) in Delft, first attended school in Warmond, where his mother moved as a widow, and then in Benthuizen, where an uncle was to prepare him for an administrative office. However, he did not learn foreign languages or Latin, which he later lacked. In 1648, he became a bookkeeper and cashier for a cloth merchant in Amsterdam. Perhaps it was there that his interest in studying nature awakened; possibly he visited the collection of natural history objects owned by Swammerdam's father, which was famous. In 1653 or 1654, he returned to Delft and lived there for the rest of his life.

Throughout his work, Van Leeuwenhoek dedicated himself with great zeal to the study of nature. He was a self-taught individual who excelled particularly as a microscopist. We owe him a significant improvement in the microscope. He manufactured these instruments himself in large numbers: through his own practice, he acquired extraordinary skill in metalworking, glass blowing, grinding, and polishing lenses. He learned glass blowing at the lamp from a glass blower who demonstrated his craft at a fair. He carefully selected the types of glass for his lenses, which were very clear, making the best microscopes of his time. He owned 527 of them, mounted in copper, some in silver, and a few in gold; their magnification ranged from 40 to 270 times. He was very cautious with his instruments, did not lend them out, and initially did not even show the best ones. The way he ground his lenses was kept a secret, and he was generally not inclined to teach his art to others. He was the first to attach a concave mirror to the microscope to enhance the light falling on the object. His keen observational skill is evident from the great accuracy of some of his measurements, and his steady hand and enduring patience from the neatness of his microscopic preparations.

Anker Smith

1798

Engraving, 15 x 20 cm

Private Collection, London

Throughout his work, Van Leeuwenhoek dedicated himself with great zeal to the study of nature. He was a self-taught individual who excelled particularly as a microscopist. We owe him a significant improvement in the microscope. He manufactured these instruments himself in large numbers: through his own practice, he acquired extraordinary skill in metalworking, glass blowing, grinding, and polishing lenses. He learned glass blowing at the lamp from a glass blower who demonstrated his craft at a fair. He carefully selected the types of glass for his lenses, which were very clear, making the best microscopes of his time. He owned 527 of them, mounted in copper, some in silver, and a few in gold; their magnification ranged from 40 to 270 times. He was very cautious with his instruments, did not lend them out, and initially did not even show the best ones. The way he ground his lenses was kept a secret, and he was generally not inclined to teach his art to others. He was the first to attach a concave mirror to the microscope to enhance the light falling on the object. His keen observational skill is evident from the great accuracy of some of his measurements, and his steady hand and enduring patience from the neatness of his microscopic preparations.

Van Leeuwenhoek and his Microscopes

Van Leeuwenhoek never reveaedl the exact methods he used to construct his microscopes, keeping the details of his lens-making techniques a closely guarded secret throughout his life. While he was open about his observations and provided detailed descriptions of what he saw, he did not teach others how to replicate the lenses or microscopes he used. This secrecy likely stemmed from his desire to maintain control over the quality of his work and the uniqueness of his discoveries.

Van Leeuwenhoek's microscopes were simple, consisting of a small, hand-ground lens mounted between two brass or silver plates. These lenses were capable of extraordinary magnification, sometimes exceeding 200x, far surpassing the compound microscopes available at the time. His method likely involved heating glass to create a small sphere, which he then carefully ground and polished into a precise shape. However, the exact process he used to achieve the clarity and magnifying power of his lenses remains uncertain.

Jeroen Rouwkema

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/rouwkema/2262158965/

Van Leeuwenhoek's microscopes were simple, consisting of a small, hand-ground lens mounted between two brass or silver plates. These lenses were capable of extraordinary magnification, sometimes exceeding 200x, far surpassing the compound microscopes available at the time. His method likely involved heating glass to create a small sphere, which he then carefully ground and polished into a precise shape. However, the exact process he used to achieve the clarity and magnifying power of his lenses remains uncertain.

Although others, such as Robert Hooke, attempted to replicate Van Leeuwenhoek’s lenses, they were rarely able to match their quality. Hooke himself acknowledged the superiority of Van Leeuwenhoek’s microscopes, despite being a skilled microscopist in his own right.

Van Leeuwenhoek’s reluctance to share his methods may have been rooted in both personal and professional motivations. He did not belong to the academic or scientific institutions of his time and operated as an independent researcher. By withholding his techniques, he maintained a competitive edge and protected the originality of his findings. This secrecy, however, had consequences for the scientific community. Without access to similar instruments, other researchers were unable to replicate many of his observations during his lifetime, which initially led to skepticism about some of his claims.

Even after his death in 1723, Van Leeuwenhoek’s microscopes and methods were not widely understood. While some of his instruments were preserved and studied, it would take decades for lens-making technology to advance to a point where microscopes of comparable quality became widely available Despite his secrecy, Van Leeuwenhoek’s work inspired future generations of scientists. His detailed descriptions and meticulous documentation of his findings helped lay the groundwork for microbiology and other fields of study. By demonstrating what was possible with high-quality microscopes, he encouraged the continued development of optical instruments, eventually leading to the advanced microscopes used in modern science.

Van Leeuwenhoek and the Royal Society

Van Leeuwenhoek’s relationship with the Royal Society unfolded during a period of significant scientific and political transformation in Europe, spanning multiple decades and intersecting with major conflicts, including the Anglo-Dutch Wars and other European struggles. Despite these turbulent events, his correspondence with the Society persisted, illustrating how the pursuit of scientific knowledge often transcended political and national rivalries.

Van Leeuwenhoek first contacted the Royal Society in 1673, at the height of the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–1674), a conflict in which England and France aligned against the Dutch Republic. The political climate could have impeded the flow of correspondence, but Van Leeuwenhoek, working in relative isolation in Delft, sent a letter detailing his microscopic observations of mold and the anatomy of a bee. This letter, written in Dutch, was received and translated for the Society by its secretary, Henry Oldenburg. Oldenburg played a crucial role in fostering communication, bridging the linguistic and geographical gap between Delft and London. The Royal Society, founded in 1660 under the reign of Charles II, sought to establish itself as a hub for empirical science, making Van Leeuwenhoek’s novel discoveries particularly appealing.

Skepticism greeted Van Leeuwenhoek’s early claims. The discoveries he described—such as the intricate structures he observed in mold and his observations of blood cells in 1674—were so unprecedented that many doubted their validity. This skepticism did not deter Van Leeuwenhoek, who continued to refine his techniques for grinding lenses, producing microscopes capable of unparalleled magnification. Over time, as his observations were verified by others, including visitors to Delft who reported their findings to London, Van Leeuwenhoek gained the Royal Society’s trust.

In 1676, during the aftermath of the Franco-Dutch War (1672–1678), Van Leeuwenhoek reported one of his most groundbreaking discoveries: the observation of microorganisms, which he referred to as "animalcules." These tiny life forms, previously unknown to science, were seen in samples of water, including rainwater, pond water, and even his own saliva. This discovery marked a turning point, as the Royal Society began to recognize the value of Van Leeuwenhoek’s work. His letters describing these findings were published in the Society’s journal, Philosophical Transactions, providing an international platform for his discoveries.

The period from the 1680s to the 1690s was marked by frequent correspondence between Van Leeuwenhoek and the Royal Society. These decades were not without their challenges, as the Nine Years’ War (1688–1697) created political instability across Europe. Despite this, Van Leeuwenhoek continued to send detailed accounts of his observations. In 1683, he described bacteria found in the human mouth, pushing the boundaries of what was known about microscopic life. The Royal Society, keen to verify these discoveries, sent delegations to Delft on multiple occasions. Delegates witnessed his demonstrations and confirmed his findings, further solidifying his reputation.

Throughout these interactions, Van Leeuwenhoek maintained a unique position. He was not formally trained as a scientist and never became a member of the Royal Society, yet he contributed more than 200 letters over the course of his life. His letters were meticulously detailed, often including measurements and descriptions that were far ahead of their time. While he lacked the formalized language of contemporary natural philosophy, his empirical approach and the precision of his lenses earned him a lasting place in scientific history.

The early eighteenth century, during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), marked the later years of Van Leeuwenhoek’s correspondence with the Royal Society. His observations expanded to include the microscopic structure of sperm cells, plant tissues, and various other biological phenomena. Despite his advancing age, Van Leeuwenhoek’s work showed no signs of slowing, and his letters continued to be translated and published by the Society. His discoveries laid the groundwork for fields such as microbiology and histology, influencing generations of scientists.

Van Leeuwenhoek and his Illustrations

While Van Leeuwenhoek himself was not a draftsman, he relied on skilled illustrators to create visual representations of his observations. Despite the importance of these contributions, the identities of the artists and skilled workers who assisted him remain largely unknown. This lack of attribution reflects both the practices of the time and the personal reticence of Van Leeuwenhoek, who rarely acknowledged their contributions in his letters.

Living in Delft, Van Leeuwenhoek was well-positioned to collaborate with local draftsmen, engravers, or artisans. Delft, a city renowned for its artistic and scientific achievements in the seventeenth century, was home to skilled individuals capable of producing the detailed and precise illustrations required to depict van Leeuwenhoek’s microscopic discoveries. Accuracy was paramount, as these illustrations needed to demonstrate the novelty and legitimacy of his findings to others, particularly skeptical members of the scientific community.

Many of Van Leeuwenhoek’s letters to the Royal Society included descriptions of his observations, and some also contained rough sketches.Antonie van Leeuwenhoek’s letters are conserved in several institutions, with the largest collection held by the Royal Society of London, the organization with which he corresponded extensively between 1673 and 1723. These letters, originally written in Dutch, were often translated into Latin or English for publication in the Society’s journal, Philosophical Transactions. The Royal Society’s collection includes both the original Dutch texts and the translations used for dissemination. These were either refined by illustrators under Van Leeuwenhoek’s direction or reinterpreted by engravers employed by the Royal Society for publication in Philosophical Transactions. The Royal Society often relied on its own draftsmen to prepare polished engravings based on the information Van Leeuwenhoek provided. This process, however, introduced a degree of interpretation, as the illustrators translated his observations into finalized images.

Although the specific individuals who assisted Van Leeuwenhoek remain unidentified, their work was undoubtedly informed by the broader Dutch tradition of scientific and naturalist illustration, which emphasized precision and fidelity to nature. This tradition was exemplified by figures like Maria Sibylla Merian, whose work set high standards for depicting the natural world. Van Leeuwenhoek’s illustrators, whether local draftsmen or engravers associated with the Royal Society, likely adhered to similar principles to ensure the credibility of his observations.

Despite their anonymity, these illustrators made an indispensable contribution to the dissemination of Van Leeuwenhoek’s discoveries. Their ability to translate his descriptions and observations into detailed visual forms was crucial, particularly as most of his contemporaries lacked access to microscopes of comparable quality. These illustrations helped overcome skepticism by providing tangible evidence of phenomena, such as bacteria and protozoa, that were previously unimaginable.

Van Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer

The connection between Van Leeuwenhoek, citizen of Delft and father of microbiology, and Vermeer has tantalized art historians for at least a generation. Both men were baptized within a few days of each other in October 1632. They lived a few minutes' walk from one another and both were fascinated by state-of-the-art optical devices and optics, perhaps even their philosophical ramifications. However, although writers from various disciplines have speculated on the ties between the great Delft scientist and the great Delft artist, only one documented contact between them has been registered, albeit, when the artist was already dead but the scientist still alive (Van Leeuwenhoek would survive Vermeer by 48 years).

In the 17th century Netherlands, the terms "scientist" and "natural philosopher" did not carry the distinct meanings they do today. The concept of a "scientist" as a specialized professional engaged in empirical research and experimentation only emerged in the 19th century. During the time of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, such individuals were often referred to as "natural philosophers," a designation that encompassed a broad inquiry into the natural world, blending observation, speculation, and philosophy.

Natural philosophy in the 17th century was rooted in the traditions of Aristotelian thought and medieval scholasticism, although it was increasingly influenced by the methods of empirical investigation championed by figures like Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) and Francis Bacon (1561–1626). It was a time when the boundaries between disciplines were fluid, and individuals could make significant contributions without formal training or institutional support.

Van Leeuwenhoek exemplifies this transitional period. Known today for his pioneering work in microscopy, he was a self-taught craftsman who developed high-quality lenses and used them to explore the microscopic world. Van Leeuwenhoek’s discoveries, including descriptions of bacteria, sperm cells, and the microscopic structure of plants and animals, were groundbreaking. Yet, his approach differed markedly from the systematic methods and theoretical frameworks we associate with modern science.

Rather than working in academic institutions or laboratories, Van Leeuwenhoek pursued his studies independently in Delft, corresponding with the Royal Society in London to share his findings. He did not formulate grand theories or hypotheses but meticulously documented his observations, providing detailed and accurate descriptions that advanced the understanding of biology and microbiology.

This raises the question: should Van Leeuwenhoek be regarded as a scientist or a natural philosopher? The answer lies in recognizing that he was both a product of his time and a precursor to modern science. His reliance on empirical observation and technological innovation aligns with scientific practices, while his lack of formal theoretical grounding places him within the tradition of natural philosophy.

In understanding Van Leeuwenhoek's contributions, it is essential to appreciate the broader historical context of science in the 17th century. The Dutch Golden Age was marked by a flourishing of trade, art, and intellectual exchange. Natural philosophy and scientific inquiry were supported by wealthy patrons and institutions like the Royal Society and by the Dutch Republic’s relatively open intellectual climate. Figures such as Christiaan Huygens, another notable Dutch contributor, further illustrate the fluidity between disciplines at the time.

The emergence of "true scientists" began with individuals like Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), who combined observation, mathematics, and experimentation to formulate laws of motion and astronomy. Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) built on these principles with his laws of planetary motion. Robert Boyle (1627–1691), often regarded as the father of modern chemistry, emphasized controlled experiments and published his findings in a systematic manner. Isaac Newton (1643––1727) unified the fields of physics and mathematics through his laws of motion and universal gravitation.

The idea of the "scientist" as a distinct profession took shape in the early 19th century. William Whewell (1794–1866), an English polymath, coined the term "scientist" in 1834 to describe individuals engaged in systematic scientific research, distinguishing them from philosophers and amateur naturalists.

The scientific method, as a structured approach to inquiry, developed gradually over centuries. Its foundations were laid by figures like Francis Bacon, who advocated for inductive reasoning in his 1620 work Novum Organum, and René Descartes (1596–1650), who emphasized deduction and methodological skepticism. The modern scientific method, characterized by hypothesis testing, controlled experiments, and reproducibility, crystallized during the 17th century and was refined by later thinkers.

Thus, Van Leeuwenhoek's work stands at the crossroads of natural philosophy and science. While he may not have been a "scientist" in the modern sense, his meticulous investigations and technological ingenuity laid the groundwork for future scientific advances. In this light, the distinction between natural philosopher and scientist becomes less a matter of classification and more a testament to the evolving nature of intellectual inquiry.

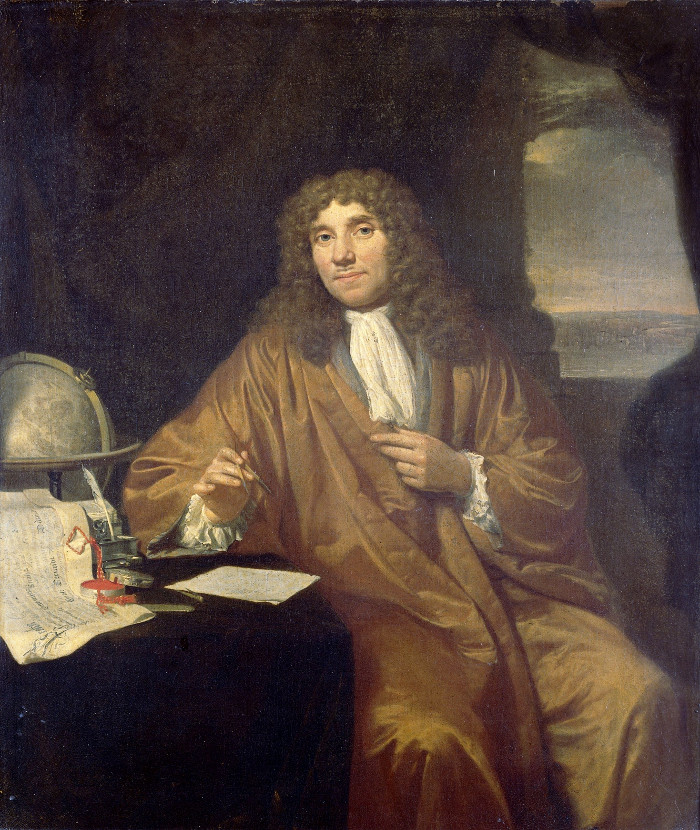

Jan Verkolje (I)

Oil on canvas, 56 x 47.5 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Both men worked with lenses. And both men were ambitious. An experienced businessman, Van Leeuwenhoek realized that if his simple method for creating the critically important lens were revealed, the scientific community of his time would likely disregard or even forget his role in microscopy. He therefore allowed others to believe that he was laboriously spending most of his nights and free time grinding increasingly tiny lenses to use in microscopes. After seven years, and a dozen letters published in their peer-reviewed journal, Philosophical Transactions, the Royal Society of London elected him a Fellow in 1680.

On the other hand, when Vermeer painted his masterwork, The Art of Painting, with its compositional complexity, exceptional dimensions and grand theme whereby the artist could claim eternal fame through his art, he left no doubt as to his lofty ambitions. And although there is no objective proof in regards, circumstantial evidence strongly suggests that the courting Vermeer had made serious inroads among upper crust of elite art collectors and men of culture in and around Delft.

For Van Leeuwenhoek, observation of the microscopic world through his tiny, hand-made devices (he made more than 200 of them in his lifetime) carried with it an implicit confirmation of God's creation. After having seen teeming "animacules" in water drawn from his gutter he wrote:

Once more we see here the unconceivable Providence, perfection, and order bestowed by the Lord Creator of the Universe upon such little creatures which escape our bare eye, in order that their kind shouldn't die out.

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

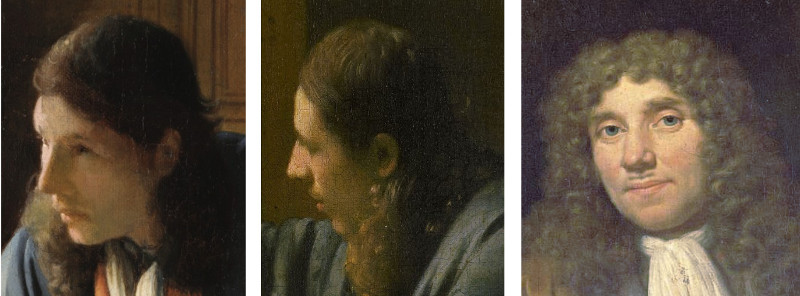

Anonymous

c. 1725

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Vermeer, Van Leeuwenhoek, and the Camera Obscura

The art historian Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. speculated that the Vermeer and Van Leeuwenhoek must have interacted; they had too much in common and Delft was too small not to notice each other's exceptional activities. Vermeer's father and Van Leeuwenhoek could have easily made each other's acquaintance through their dealings in the silk-weaving business (Vermeer's father was a caffa weaver and Van Leeuwenhoek traded in silk goods for a living). Moreover, according to Wheelock, "they probably shared interests in globes and maps which was somewhat of an obsession among men of knowledge of the time," although maps and globes were standard fixtures in many Dutch paintings and homes of Dutch burghers. Van Leeuwenhoek, then, would have know everything Vermeer needed in order to build a camera obscura, he was an expert lens maker and he was interested in optical phenomena. But from a practical point of view, the artist could have acquired the same technical knowledge or even a ready built camera based on other sources.Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., "Perspective, Optics and Delft Artists Around 1650" (New York and London: Garland, 1977), 284. In fact, the only component of the camera obscura that cannot be easily fabricated with thin wood planks, oiled paper, a small saw and a few nails, is a convex lens necessary to produce a brighter image than the original pin-point hole through which light entered the camera (indispensable for use in painting). Lens grinding was a taxing and exacting procedure in glass, based on the centuries-old technique of grinding lenses for eye-glasses (spectacles).Douglas Anderson, "Tiny Lenses," Lens on Leeuwenhoek, accessed November 14, 2023.

Moreover, Montias doubts that Van Leeuwenhoek could have been "appointed to the curatorship of the artist's estate because he was a friend of the family." since there is not evidence of any connections between the scientist and Vermeer and his family, which "would have been expected to show up if they had regular dealings with each other." There is also no evidence that Van Leeuwenhoek assumed a favorable disposition towards the interests of Catharina, Vermeer's widow, during his curatorship of the Vermeer estate or that the two great achievers had any direct contact..

Carsten Wirth weighs in noting that for Vermeer, observation of overlooked moments of daily life through his camera obscura revealed aspects of nature, and perhaps of vision itself, that inspired paintings that were broader in scope and intellectual depth than the works of any other genre painter of the time.Carsten Wirth, "The Camera Obscura as a Model of a New Concept of Mimesis in Seventeenth-Century Painting. Inside the Camera Obscura–Optics and Art under the Spell of the Projected Image," Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, 2007, 177, . Upon viewing a few pieces of stale bread and worn kitchen crockery lit by the sun through the lens of his camera obscura, he depicted, perhaps, one of the most arresting passages in European easel painting, the still life of the Milkmaid. For both the artist and scientist then, only a tiny fraction of the world and a state-of-the-art optical device were needed to uncover worlds much larger. The camera obscura opens up a new view of things for the painter; like the microscope and telescope it is an instrument of enquiring sight.

Did Vermeer Come into Contact with the Camera Obscura through the Jesuits?

The research of the Vermeer specialist Gregor Weber Gregor Weber, Johannes Vermeer: Faith, Light and Reflection (Rotterdam: nai010 publishers, 2023). has recently proposed a fresh perspective on how Vermeer might have encountered the camera obscura. Traditionally, scholars have emphasized the lay avenues—connections with Delft's scientific community, such as Van Leeuwenhoek and other amateur optics enthusiasts in Delft, or the broader dissemination of optical instruments through artisan networks. However, Weber proposes that Vermeer’s Catholic environment, particularly his proximity to Jesuit intellectual and artistic traditions, offered an alternative route. The Jesuits, renowned for their academic rigor and engagement with natural sciences, including optics, were deeply invested in visual culture. Their writings often explored light and vision, making optical devices like the camera obscura a fitting tool for both scientific inquiry and spiritual contemplation.

For the Jesuits, light was much more than a physical phenomenon. It was a sacred medium that bridged the human and divine, a source of insight into God’s creation, and a powerful tool for inspiring spiritual contemplation. This multifaceted approach to light influenced not only their religious practices but also the broader artistic and scientific discourse of the Baroque era.

Weber highlights how Jesuit devotional literature frequently incorporated metaphors of light and optical effects to discuss divine illumination. Vermeer, living near a Jesuit station in Delft, would have been exposed to these concepts not only through personal interactions but also through the religious texts and artworks associated with this community. The Jesuits used emblemata and visual representations to teach theological ideas, and the camera obscura's ability to create lifelike images could have been interpreted as a metaphor for divine creation. These theological and artistic principles may have influenced Vermeer’s practice, particularly his extraordinary treatment of light and space.

Weber also draws connections between the Jesuit use of the camera obscura and specific aspects of Vermeer’s paintings. The meticulous rendering of light, shadow, and reflection in his interiors suggests not just technical skill but also an engagement with the interplay between material reality and spiritual significance—a theme resonant in Jesuit thought. In works like The Allegory of the Catholic Faith, elements of composition and symbolism align closely with Jesuit iconography, further strengthening the argument for their influence on Vermeer’s artistic and intellectual development.

The Jesuits held a profound reverence for light, regarding it as both a physical and spiritual phenomenon that revealed the order and beauty of divine creation. In their theological framework, light symbolized divine grace and truth, illuminating the soul and guiding it toward God. This symbolic association was central to their devotional literature and art, where radiant light often represented the presence of the divine, as seen in depictions of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the saints. Through light, they conveyed the transformative power of faith and spiritual enlightenment.

Their interest in light extended beyond metaphor to include rigorous scientific inquiry. Jesuit scholars engaged deeply with optics, studying the properties of light and its behavior through lenses, prisms, and mirrors. They considered optical devices such as the camera obscura not only as tools for understanding the physical world but also as instruments that mirrored God’s intricate design. These studies reflected their broader belief that scientific exploration was a pathway to understanding divine wisdom, bridging the material and spiritual realms, and may, according to Weber, have infuenced Vermeer's treatment and understanding of light.

The Jesuits also harnessed the symbolic and emotional power of light in their art and architecture. They frequently employed dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, or chiaroscuro, to create visual narratives that engaged the senses and inspired devotion. In their churches, light was used with deliberate precision, with windows and reflective surfaces positioned to evoke a sense of the divine presence, aligning with the Counter-Reformation’s emphasis on sensory experience as a pathway to faith.

This interpretation broadens the understanding of Vermeer’s relationship with optics. It situates his use of the camera obscura not merely as a practical tool but, according to Weber, as part of a larger cultural and religious framework, although, admittedly, Weber does not provide a documented link between Jesuit thinking and Vermeer's use of light or the camera obscura.

Did Vermeer Hide his Camera Obscura?

We do not know if Vermeer made public his use of the camera obscura, but neither a complete apparatus nor lenses of any sort were found in his studio after his death. Thus, the camera obscura began to be associated with the artist only in the late 1800s with the advent of modern photography.

Jan Lievens

1628/29

Oil on panel, 99 x 84 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

On one hand, the camera obscura had been openly publicized and enthusiastically recommended to painters by Constantijn Huygens fig. 2, the Dutch connoisseur par excellence. On the other, the enigmatic painter Johannes Torrentius attempted to hide from Huygens the fact that he had used the device in his own canvases (of which only one has survived).

As Huygens recounts in his memoirs, when he showed up at the artist's studio and demonstrated how a camera obscura that he had acquired in London functions, the painter, "on seeing the projections, pretended not to know how the apparatus worked. He had asked innocently if the dancing figures on the screen were live figures outdoors. This question surprised Huygens, the instrument had, after all, been shown to many painters and everybody knew about it. Huygens suspected 'this cunning fox,' when painting, of using such an instrument to achieve his special effects."

Torrentius, then must have already known the device and had achieved, according to Huygens, "especially by this means [the camera obscura]… that certain quality in his paintings which the general run of people ascribe to divine inspiration."

Thus, the camera was lauded by Huygens but concealed by the only Dutch seventeenth-century artist other than Vermeer who is known to have actually used it as an aid to painting.

Could it be that Vermeer, like Torrentius, chose to hide his involvement with the camera in order not to diminish his artistic accomplishments in the eyes of his contemporaries? If he desired so, he must have had a difficult time.

Huygens lived an hour's walk from Vermeer's Delft and was likely very aware of Vermeer's presence and was the principal promoter of the device amongst Dutch artists. Moreover, anyone familiar with the camera has no trouble tracing various stylistic peculiarities of Vermeer's paintings to the camera's image produced by imperfect lens and focal limits.

Did Van Leeuwenhoek Pose for Vermeer?

Various art historians have mused that Van Leeuwenhoek might have posed for both The Astronomer and The Geographer by Vermeer (fig. 3). Considering the manner in which the scientist had himself portrayed by Jan Verkolje (fig. 1), one of the most fashionable painters of the time, it is difficult to imagine that he would not have been in synchrony with the refined dignity with which Vermeer's two scientists are depicted and the nobility of the scientist's quest.

On the other hand, John Michael Montias's views the artist-scientist relationship, and consequentially the likelihood that Van Leeuwenhoek had commissioned the two pictures, with circumspection.John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 225–226. He finds no particular resemblance between "the elegant, distinguished looking scholars" and the "coarse features" exhibited in known portraits of Leeuwenhoek. Certainly, the two men in Vermeer's probable pendants do not look much like Van Leeuwenhoek as he was portrayed by Verkolje. But those who hold fast to the idea that Vermeer did paint the scientist are comforted by the fact that Verkolje painted a fifty-year-old-man and not one of thirty-seven.

Michael van Musscher

1671

Medium oil on canvas, 59.5 x 23.4 cm.

Amsterdam Museum, Amsterdam

Similar in cut and fabric to the Japonsche roks worn by Vermeer's geographer and astronomer—one pale blue with fancy orange cuffs and the other marine green—Van Leeuwenhoek had donned on a plush yellow rok of his own for his formal portrait. Roks, a highly desired garment imported from Japan by the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC), were essentially a kimono tailored into a kind of house robe. They were especially worn by scholars in their studios who wished to distinguish themselves from mere dabblers. They appear in a great many Dutch paintings of doctors, geographers and astronomers (fig. 4). By the mid-seventeenth century, roks were made from imported Indian and Chinese silk and became a more common imitation ware but in Vermeer's and Van Leeuwenhoek's day, to wear a rok is to wear a garment which had not yet been commodified. The robe typically featured a loose-fitting design, made from rich fabrics such as silk, with elaborate patterns influenced by both Japanese and European aesthetics. In many portraits from the period, such as those by Rembrandt and other Dutch Golden Age painters, the Japonsche rok is depicted, signifying both wealth and the wearer's connection to the broader world of trade and exotic goods. However, that Van Leeuwenhoek would have been willing to model for not one, but three elaborate, labour-intensive paintings done by cutting-edge artists of the day may or may not have been in character with the Delft scientist.

Similar in cut and fabric to the Japonsche roks worn by Vermeer's geographer and astronomer—one pale blue with fancy orange cuffs and the other marine green—Van Leeuwenhoek had donned on a plush yellow rok of his own for his formal portrait. Roks, a highly desired garment imported from Japan by the VOC (Dutch East India Company), were essentially a kimono tailored into a kind of house robe. They were especially worn by scholars in their studios who wished to distinguish themselves from mere dabblers. They appear in a great many Dutch paintings of doctors, geographers and astronomers. By the mid-seventeenth century, roks were made from imported Indian and Chinese silk and became a more common imitation ware but in Vermeer's and Van Leeuwenhoek's day, to wear a rok is to wear a garment which had not yet been commodified. The robe typically featured a loose-fitting design, made from rich fabrics such as silk, with elaborate patterns influenced by both Japanese and European aesthetics. In many portraits from the period, such as those by Rembrandt and other Dutch Golden Age painters, the Japonsche rok is depicted, signifying both wealth and the wearer's connection to the broader world of trade and exotic goods. However, that Van Leeuwenhoek would have been willing to model for not one, but three elaborate, labour-intensive paintings done by cutting-edge artists of the day may or may not have been in character with the Delft scientist.

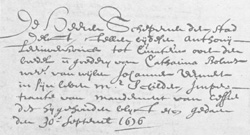

Van Leeuwenhoek and the Estate of Vermeer

On September 30, 1676, a year after the artist's death, the town council of Delft designated Van Leeuwenhoek to administer the assets of Vermeer's wife, Catharina Bolnes, "widow of the late Johannes Vermeer during his lifetime master painter." This was not the first time Van Leeuwenhoek had been appointed as an estate executor. But since the job was likely to procure more worries than benefits, one writer concluded that Leeuwenhoek's acceptance of the more or less insolvent Vermeer estate suggests, according toe Anthony Bailey, some acquaintance between the two men.Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2001), 165.

Catharinas' effort to preserve her husband's masterpiece, The Art of Painting, as part of her inheritance and to prevent its auction, almost certainly failed. Van Leeuwenhoek noticed this omission in the inventory and summarily reclaimed the painting having discovered it in Vermeer's mother-in-law's household. Van Leeuwenhoek rightfully determined that the transferal of the work to the late painter's mother-in-law, Maria Thins, had been illegal. The Art of Painting and other works, most likely as a part of the artist's stock and trade, were auctioned off on May 15, 1677.

"Hier Rust Antonie van Leeuwenhoek out synde 90 jaar, 10 maanden en 2 dagen. Heeft elk, o wandelaer alom ontzagh voor hoogen ouderdom en wonderbare gaven. Soo set eerbiedigh hier uw stap. Hier legt de gryse wetenschap in Leeuwenhoek begraven."[Here rests Antonie van Leeuwenhoek having reached the age of 90 years, 10 months and two days. O stroller, be respectful of great old age and wonder.]

Montias also noted that in 1678, Van Leeuwenhoek, having gotten wind that Vermeer's wife Catharina Bolnes had inherited a house in Gouda (where Catharina's mother was born) in which her father had lived and died, and three morgen of land in Wilnis, empowered the Thins family notary in Gouda to sell the properties on behalf of Vermeer's bankrupt estate, presumably for the benefit of the creditors.

The art historian Gary Schwartz argues that the "romanticization of the ties between Antonie van Leeuwenhoek and Johannes Vermeer does injustice to the historical record… The curator of an estate has permissible options that can benefit the heirs to a bankrupt estate. Van Leeuwenhoek did not employ them.

Furthermore, "he came up consistently for the rights of the creditors rather than Vermeer's widow Catharina Bolnes and her mother, Maria Thins. Montias holds him accountable for "the allegation … that Maria Thins and her daughter had conspired to conceal some of Catharina's assets," which would have landed them in jail had they not been able to prove it was a lie. In one action in which he was entirely free to show sympathy for the heirs, he behaved oppositely, by charging Maria Thins sixty guilders for his services as curator. Are we to believe that as she paid up she thought of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek as a good friend and collaborator of her deceased son-in-law?"

Publications, Websites and Resources

- Anderson, Douglas. Lens on Leeuwenhoek. http://lensonleeuwenhoek.net/overview.htm.

- Dobell, C., ed. 1960. Antony Van Leeuwenhoek and His 'Little Animals'. New York: Dover Publications.

- Ford, B. J. 1991. The Leeuwenhoek Legacy. Bristol: Biopress; London: Farrand Press.

- Huerta, Robert D. 2003. Giants of Delft: Johannes Vermeer and the Natural Philosophers: The Parallel Search for Knowledge During the Age of Discovery.

- Leeuwenhoek, van Antonie. 2010. The Select Works of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, Containing His Microscopical Discoveries in Many of the Works of Nature.

- Loncke, Hans. 2007. "Making a Van Leeuwenhoek Microscope Lens." In Microscopu-UK, April. http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/mag/indexmag.html?http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/mag/artapr07/hl-scope.html.

- Loncke, Hans. 2007. "Making an Antonie van Leeuwenhoek Microscope Replica." In Microscopu-UK, July. http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/mag/indexmag.html?http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/mag/artjul07/hl-loncke2.html.

- "How to Build a Camera Obscura." Education. J. Paul Getty Museum. http://www.getty.edu/education/teachers/classroom_resources/tips_tools/downloads/aa_camera_obscura.pdf.

- Schwartz, Gary. 2016. "Today in Delft 340 Years Ago," September 30.