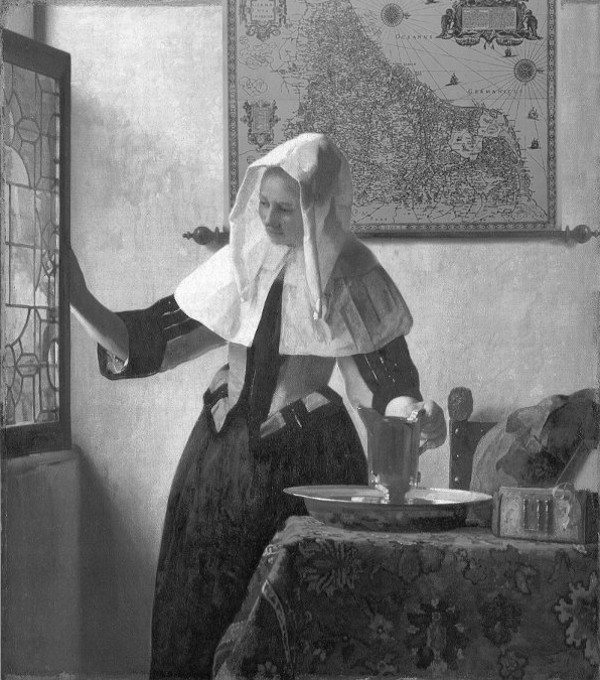

In the early and mid 1660s, Vermeer painted a group of closely related works which the art historian Lawrence Gowing called the "pearl pictures" (see box below) in honor of their exquisite facture and for the fact that each work features a pearl necklace. In these compositions the artist made a decisive move away from the cubical interior spaces, which he and Pieter de Hooch had brought to near formal perfection, and "adopted an approach that in some respects was closer to that of the Leiden artists Gabrriel Metsu and Frans van Mieris. The preoccupation with linear perspective and geometric order diminished in favor of simpler compositions, in which the view is usually brought closer, only one figure is depicted and the behavior of light becomes the predominant aesthetic concern."Walter Liedtke, Michiel C. Plomp, and Axel Rüger, Vermeer and the Delft School (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001), 379.

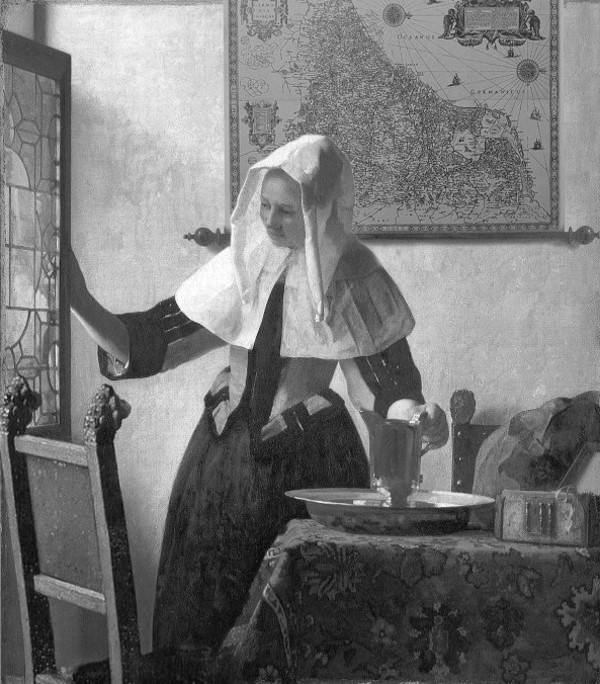

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 45.7 x 40.6 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

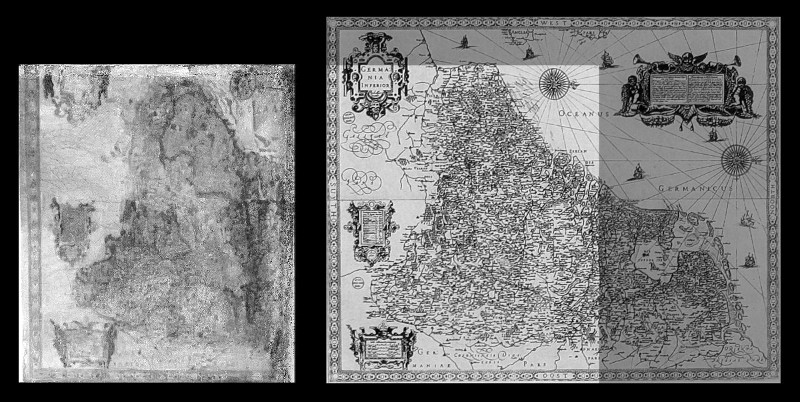

The importance given by Vermeer to the planimetric organization of these pictures can be deduced by the numerous compositional alterations which were made in the course of the painting process, some of which have been revealed with the aid of modern scientific instruments. Such changes are clearly seen in a group of infrared reflectogramsInfrared reflectography (IRR) is an imaging technique used to study the presence of specific pigments beneath visible paint layers. This technique provides valuable information for art historians as changes in composition detectable during different phases of a painting's execution become evident. Furthermore, IRR can reveal paint losses and retouchings, sometimes invisible to the naked eye. Infrared radiation allows for a "see-through" view of paint layers impenetrable to human sight, as it either passes through paint until absorption occurs or reflects back to the camera. Though infrared light's wavelength is too long for human perception, it can be photographed. IRR can penetrate most thinly painted oil paints, except for carbon black, which was often used in artists' materials such as graphite, charcoal, and ink in early painting stages or as an additive to darken other pigments. The resulting infrared reflectogram is digitally converted by software, producing a black-and-white image on the computer monitor. As IRR detects black materials, it complements X-radiography, which typically captures lighter materials, especially lead white, commonly used by seventeenth-century European painters. of the Young Woman with a Water Pitcher, so much so that Vermeer's initial composition can be reconstructed with a reasonable degree of accuracy.

Aim of the Virtual Reconstruction

The aim of the virtual reconstruction of the Young Woman with a Water Pitcher (fig. 1) is not to ecreate the painting's exact original appearance, which is obviously impossible; but rather, to form a reasonable hypothesis of the artist's original pictorial concept and, perhaps, reveal the rationale behind his later modifications.

Technical analysis reveals that the background wall map of the Young Woman with a Water Pitcher originally extended to the left behind the woman. In addition, the back of a chair set on an angle was placed in the left foreground and partly overlapped the window. The chair, the use of an open window as a repoussoir device, and the bright, local coloring are consistent with Vermeer's style in works dating from the early 1660s.

The changes in Vermeer's composition may have been made during the early phases of the painting procedure,Jørgen Wadum, Chief Conservator of the Mauritshuis, personal communication, notes that it remains uncertain if each of the altered objects appearing together in the virtual reconstructions was ever present at a single stage of Vermeer's work. called underpainting, before color and detail had been introduced even though some parts of the foreground chair appear to have been brought to a high degree of finish. It appears that some light dots of light-colored paint, perhaps Vermeer's characteristic pointillés,Pointillés, or globular dots of paint, were intended to mimic the so-called "disks of confusion" produced by the camera obscura image. Vermeer extensively employed pointillés throughout his career to enhance the sensation of light. can be made out along the uppermost profile of one of the chair's lion-head finial. In the simplest terms, an underpainting is essentially a monochrome version of a painting (usually executed with brown or neutral gray paint) in which the artist fixes on his canvas the fundamental elements of composition, creates the sensation of volume and distributes darks and lights in order to produce an overall effect of illumination. The underpainting allows the painter to envision his pictorial idea with a minimum expenditure of time and effort while maintaining control over pictorial unity, one of the principal requisites Baroque painting. The parts of the underpainting that did not live up to the artist's expectations could be immediately observed and corrected with relative ease before moving on to complex problems of color and fine detail.

The present reconstruction of the Young Woman with a Water Pitcher is based primarily upon a group of infrared reflectograms of the painting and Arthur K. Wheelock 's analysis of the technique and expressive content of the work as they relate to the compositional alterations.Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Vermeer and the Art of Painting (New York and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 105–109. By comparing the reconstructed versions to the final version which we now see (part two), we might be able to intuit how the artist "thought through" his pictures and make a few observations about why Vermeer revised his initial pictorial concept so profoundly.

Changes in Composition

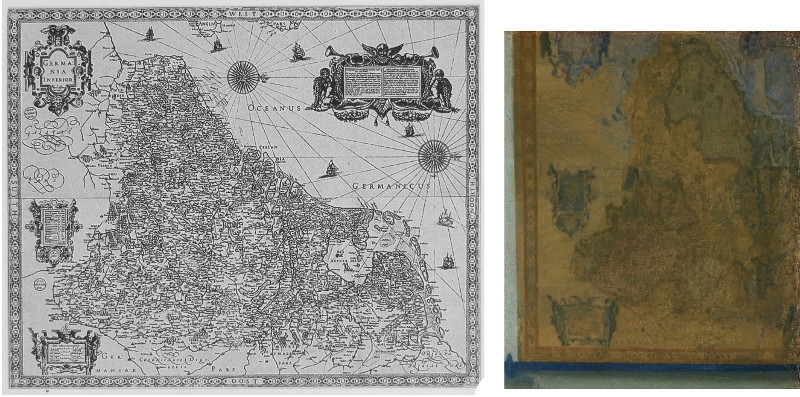

As stated before, during the course of his work, Vermeer made two significant compositional modifications in Young Woman with a Water Pitcher. Firstly, the background map of the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands (fig. 3), based upon a known map published in 1671 by Hendrik Hondius I (fig. 2), which was initially extended behind the young girl's head, was moved to the right. The original position of its left-hand contour can be perceived with the naked eye as a barely perceptible shift in tone of the wall slightly to the left of the figure's head. This shift in tone is not always visible in reproductions but is apparent when viewing the actual canvas. The second alteration was the removal of a so-called Spanish chair with lion-head finials, a familiar prop in Vermeer's and Dutch interiors, from the left-hand foreground. The reflectograms also show that the artist had initially depicted the contours of the water basin differently. These last alterations are not accounted for in the reconstruction.

Published in The Hague by Hendrik Hondius IUntil recently, it ws held that the autor of this map wa Huyck Allart. See: Landsman Rozemarijn, Jan Vermeer van Delft and Ian Wardropper. Vermeer's Maps. (New York, NY: Frick Collection, 2022). Published in association with DelMonico Books.

Unmounted, uncolored, (72 x 91 cm) overall

4 sheets, each 36.5 x 45.7 cm.

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

Fig. 3 (right) Young Woman with a Water Pitcher (detail)

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 45.7 x 40.6 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

It is generally held that Vermeer adhered to the true shape dimensions of the real objects that he pictured in his interiors. As the art historian James Welu has shown in several cases it has been possible to identify not just the map's designers and publishers, but the specific editions.The plates, sourced from the early seventeenth century, were embellished with decorative elements and reprinted. James A. Welu, "Vermeer: His Cartographic Source," Art Bulletin 57 (December 1975): 529–547. Not only can the book studied by Vermeer's Astronomer be recognized; the very page at which it is open is legible. The local colors of the objects, instead, are more difficult to judge since the objects habitually represented in Dutch painting, like carpets and clothing, were produced in a variety of colors and furthermore, the pigments are known to have deteriorated and changed color.

As with other maps in Vermeer's paintings (The Lute Player and The Art of Painting) the topographical features and the decorative embellishments of the map of the Young Woman Holding a Pitcher correspond very closely to those of the known map on which Vermeer's rendering is based.When Vermeer painted the map around seventy years after its initial publication, the region's borders had notably shifted. In 1648, the Dutch Republic's seven provinces declared independence, bifurcating the Low Countries. Yet, the map's 1671 edition still reflected late sixteenth-century topography. By the time it appeared in Vermeer's "Woman with a Water Pitcher," the map seemed more decorative than accurate. Its emblematic value is emphasized in Vermeer's rendition, focusing on the region's southern half. This portrayal, suggesting a unified region despite changing borders, contrasts its creation history, given its maker, Jodocus Hondius I (1563–1612), was a Southern Netherlandish refugee. Accurate regional representation might not have been this map's main objective." Landsman Rozemarijn, Jan Vermeer van Delft, and Ian Wardropper. https://amzn.to/3Max5HE. (New York, NY: Frick Collection, 2022). Published in association with DelMonico Books. Moreover, painters were dramatically limited in their choice of pigments. Only a handful of what were called "bright colors" were available in the seventeenth century.

from: Welu, James A. "Vermeer: His Cartographic Sources." The Art Bulletin 57, no. 4 (December 1975): 529-547.

Vermeer's repeated use of maps bears witness to the fact that wall maps enjoyed great vogue as interior decoration. In the seventeenth century, the decorative use of maps became so popular that many publishers began reissuing old maps specifically for this purpose. Such a map appears in Vermeer's Young Woman with a Water Jug. The wall map in this painting can be identified with a map oriented with north to the right of the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands, published by the Dutch cartographer Huyck Allart (fl. c. 1650-1675). Until recently, it ws held that the autor of this map wa Huyck Allart. See: Landsman Rozemarijn, Jan Vermeer van Delft and Ian Wardropper. Vermeer's Maps. (New York, NY: Frick Collection, 2022). Published in association with DelMonico Books. The only known example of Allart's map, which bears the date 1671, is preserved in the University Library, Leiden. The copper plates Allart used for printing his map of the Seventeen Provinces were not originated by him, but were acquired from an earlier source. Although the origin of these plates is unknown, the date of their initial engraving can be approximated by examining the unrevised geographical contents of Allart's map. The copper plates for Allart"s map were probably first engraved around the beginning of the seventeenth century.

Although Allart's map shows no revision in its geographical contents, it does contain several decorative elements that were added sometime after the original engraving to give this old map a new look. The decorative cartouche (containing the map's graphic scale) located in the lower left corner was not part of the map's original format. This cartouche, which can be seen in Vermeer"s painting, is designed to be viewed from below and to the left and the chiaroscuro on it implies a light from the upper right, whereas the two cartouches directly above are designed to be viewed straight on and the chiaroscuro on them denotes a light from the upper left. The inconsistency between the lower cartouche and the two above, which appear to be part of the map"s original format indicates that the one below is a later addition. In fact, the design for the later cartouche was taken from a much earlier source: a map of Portugal published by Ortelius in 1560. On Ortelius's map this design appears in the position for which it was originally made: the upper right corner. Another later addition to the Allart map is the large ornate cartouche at the upper right. This design, in heavy chiaroscuro, engraved about mid-seventeenth century, is characterized by a variety of naturalistic elements: putti, trumpets, the head of an angel, and several garlands of fruits and flowers all joined together on a shell-like framework. In addition, many of the vignettes of ships and the map's entire ornamental border appear by the style of their engraving to have been added to the map sometime after the original engraving.

The fact that the Allart map had been revised so extensively by the middle of the seventeenth century, in its decorative contents and not at all in its geography, clearly demonstrates that by that time the map was intended primarily as decoration. Allart's map of 1671 was published about a decade after the date usually given to Vermeer"s Woman with a Water Jug (c. 1662). This of course could call for a reconsideration of the date assigned to Vermeer"s painting. Yet to place this work after 1671 seems inconsistent with its style. It is more likely that a state of the Allart map, similar to the 1671 state, was published before the date given to Vermeer"s painting. This earlier state would have appeared sometime between the date of the map"s original engraving, c. 1600, and the date of Vermeer"s painting, c. 1662. Therefore, even though we know only one original of the Allart map, we can be quite sure that more examples—in fact, several editions—were available during the seventeenth century.

(a virtual reconstruction, first hypothesis).

(a virtual reconstruction, second hypothesis)

The present virtual reconstruction is based partly upon the assumption that while Vermeer later changed the position of the map, he maintained intact both its original dimensions and the height at which it is hung. In the final version the artist, so to speak, slid the map rightwards until its left-hand contour and rolin ballJames A. Welu identified the map as one published by Hyuck Allart. Oriented with the south to the left, a version of the map, dated 1671, is preserved in the University Library, Leiden. Allart acquired the plates from an early seventeenth-century source, incorporated decorative elements, and reprinted them. See James A. Welu, "Vermeer: His Cartographic Source," Art Bulletin 57 (December 1975): 529–547. became visible to the right of the figure's linen headdress.

As can be noted in the virtual reconstruction, the entire width of Hondius' map, including the right-hand rolin ball,The rolin balls, featured in many renditions of wall maps in Dutch interior paintings, function to separate the map's back side from wall surfaces to prevent moisture accumulation. would have been represented within the perimeters of Vermeer's canvas.

Unfortunately, with the painting in question it is not possible to verify the accuracy of the map's dimensions in respect to those of the real seventeenth-century map through a technique noted as "reverse geometry," used by the architect and scholar Philip Steadman to reconstruct a number of Vermeer's interiors. Nonetheless, Nonetheless, Steadman, who is also the author of Vermeer's Camera: Uncovering the Truth behind the Masterpieces, demonstrated that it is not just the geographical detail of the maps and the decorative detail of the chairs that are so precisely represented; their overall dimensions also correspond closely to the originals. In effect, their reconstructed heights and widths are, in all those cases where measurement is possible, within a few per cent of the surviving library copies. It would, therefore, be fairly safe to say the map is portrayed in the Young Woman with a Water Pitcher is portrayed according to its original dimensions and not likelyresized to obtain some aesthetic advantage or iconographic nuance.

However, if Vermeer took liberties with the dimensions of the map, such a change in scale should not come as a complete surprise since it is a well-known fact that Vermeer altered dimensions, sometimes greatly, of a few objects represented in his works for aesthetic or iconographic reasons. For example, the cabinet-sized painting of the Finding of Moses to the far right-hand side of The Astronomer appears far larger when it is represented in the later Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid.

The "Pearl Pictures"

In the early 1660s Vermeer executed four small canvases eloquently named the "pearl pictures" by Lawrence Gowing which are among the artist's most lucidly conceived yet enigmatic works.Lawrence Gowing, Vermeer (Oakland CA: University of California Press, 1997), reprint edition. For the present study, Young Woman with a Water Pitcher has been added to the group, obviously, not with the intention to revise Gowing's well-known term, but because the painting bears important compositional affinities with the four pearl pictures:

Left to right: (1) Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, (2)Woman Holding a Balance, (3) Woman Holding a Water Pitcher, (4)Woman with a Lute and (5)Woman with a Pearl Necklacee.

The subject matter of the pearl pictures is restricted to a single woman who momentarily engages in some discreet activity in a left-hand corner of a room, very near a window. While persistent iconographical interpretations seem to have successfully illuminated the story behind the Woman Holding a Balance, the others have resisted interpretative attempts with more success. Nonetheless, a common theme that unites the women's activities might be thoughtful reflection (or distraction).

Four of the five pictures show a slice of a window to the left and four display chairs (a second chair once occupied the lower left-hand corner of the composition of the Young Woman with a Water Pitcher). All the scenes are staged against a simple, white-washed wall set parallel to the picture plane. The particular hue and tonal values of the white-washed walls are key to establishing the direction, intensity and quality of the incoming light and constitute an unsung technical tour de force of the artist's oeuvre.

Even by Vermeer's standards, the scenes of these works are organized with exceptional economy utilizing a table with a single woman, a meager still life, a few carefully chosen props, a map or painting on the background wall and one or two chairs (infrared reflectograms reveal that the original version of Woman with a Pearl Necklace once displayed a large wall map behind the standing girl). All of the movable objects are structurally simple although some are adorned with elaborate decorative elements (ex. Turkish carpets and large wall maps).