Saint Praxedis: A Continuing Debate

"

"

1655

Oil on canvas, 101.6 x 82.6 cm. (40 x 32 1/2 in.)

Kufu Company Inc., on long-term loan to the National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo

"St Praxedis trice; Technical Examinations of St Praxedis"

Arie Wallert

https://www.essentialvermeer.com/misc/WALLERT-St-Praxedis.pdf

The painting Saint Praxedis, attributed by some scholars to Vermeer, continues to provoke heated debate. Thought to be a direct copy of an Italian work by Felice Ficherelli (1605–1669), the painting was first proposed as an early Vermeer based on a signature and date inscribed on the canvas, as well as perceived stylistic similarities to his later works. The attribution gained traction in the 1980s when curator Arthur K. Wheelock supported its inclusion in Vermeer's early oeuvre, and more recently, the painting was displayed as an authentic Vermeer in the highly anticipated Vermeer retrospective at the Rijksmuseum in 2023. However, the attribution remains fiercely contested, with some leading experts, including conservator Jørgen Wadum, rejecting the idea that Vermeer could have painted it.

Arie Wallert’s study on Saint Praxedis presents a meticulous examination of the painting’s origin, technique, and authorship, engaging with the long-standing debate over whether it can be attributed to Vermeer. The article situates Saint Praxedis within the broader context of its Italian prototype, a work by Ficherelli, and closely compares the technical features of both versions. Wallert approaches the question of attribution through material analysis, stylistic evaluation, and historical context, shedding new light on the painting’s possible relationship to Vermeer’s early career.

One of the key contributions of the study is its discussion of the materials and techniques used in Saint Praxedis. The analysis of pigments and underlayers suggests important differences between this painting and its Italian counterpart, raising the possibility that the Dutch version was produced in a different workshop environment. This evidence does not provide a definitive answer, but it strengthens the argument that the painting is not simply a copy in the traditional sense but rather a work with its own distinct material history. Wallert also engages with previous scholarship, including the arguments of Arthur K. Wheelock and Jørgen Wadum, presenting a nuanced discussion of the painting’s contested status.

The study also considers the broader implications of Saint Praxedis for our understanding of Vermeer’s early development. While the painting's dramatic composition and intense coloration differ significantly from his later domestic interiors, Wallert suggests that these characteristics do not necessarily rule out an early experiment with history painting. However, he acknowledges that the stark contrast between this work and Diana and Her Companions—often cited as Vermeer’s first known original composition—remains a major issue. The lack of preparatory drawings or related works by Vermeer in this style continues to fuel skepticism, reinforcing the uncertainty surrounding the painting's attribution.

Whether or not Saint Praxedis will ever be universally accepted as a Vermeer remains to be seen, but Wallert’s study ensures that the discussion remains as rigorous and informed as ever.

Special Vermeer/Dali exhibition

Dalí/Vermeer: A Dialogue

Meadows Museum, Dallas TX

October 16, 2022-January 15, 2023

https://meadowsmuseumdallas.org/exhibitions/dali-vermeer-a-dialogue/

:

Thanks to the generosity of the Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí in Figueres, Spain, and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, Dalí/Vermeer: A Dialogue, unites Johannes Vermeer’s Woman in Blue Reading a Letter (c. 1663) and Salvador Dalí’s interpretation thereof, The Image Disappears (1938), for the very first time.

A key part of any artist’s formal training has always been the study of their predecessors’ works, the imitation of which is seen as a crucial step in the development of one’s own style and technique. Dalí stands out as among the modern artists who most revered—indeed obsessed over—the painters that preceded him. The famed surrealist came of age just as earlier painters were being celebrated and publicized outside of their countries of origin, as was the case with the Dutch painter Vermeer, whose work he at first knew only through reproductions.

While a kind of Vermeerian iconography would come to pepper Dalí’s compositions throughout his career, less common are the instances in which the Surrealist painter reinterpreted whole compositions by Vermeer. Among these is The Image Disappears, Dalí’s interpretation of Vermeer’s Woman in Blue Reading a Letter. In The Image Disappears, whose title describes what the image does rather than what it depicts, Dalí takes the basic forms and elements of Vermeer’s composition—a woman wearing a blue night jacket, standing in profile reading a letter in front of an unseen window from which emanates soft light—and plays a visual trick on viewers, creating a second image of a mustachioed male face in profile that has been identified as that of Velázquez.

Not even Dalí would have seen these two paintings side-by-side; thus, the exhibition offers the unique opportunity to contemplate imitator and imitated within the context of the Meadows’s collection of Spanish art. The Meadows welcomes visitors to not only enjoy this rare moment to see a Vermeer in Texas, but to contemplate the broader question of imitation: is it flattery or conceit?

Additional works by Dalí from the Meadows’s collection, including works on paper, will be featured elsewhere in the museum and round out this fall’s celebration of the artist and his many evocations of art historical themes.

Mauritshuis Launches Public Girl with a Pearl Earring Contest

My Girl with a Pearl

https://www.mauritshuis.nl/en/what-s-on/mauritshuis-at-home/mygirlwithapearl/

:

Girl with a Pearl Earring is a magical painting. Many people come to the Mauritshuis from all over the world for the opportunity to stand face to face with Vermeer’s masterpiece. Others dream of doing so. For many, the painting is a source of inspiration, a muse.

:

Instagram: @mygirlwithapearl

In 2023, the spotlight will be on Johannes Vermeer, painter of our Girl, as the Rijksmuseum hosts a major exhibition of his work from early February to early June. Of course no Vermeer exhibition would be complete without Girl with a Pearl Earring, so she will be moving to Amsterdam for a while (from circa February 10 to 1 April, 2023).

Don’t worry, though–we do not intend to leave her spot on our wall empty. On the contrary: her short visit to Amsterdam provides us with a unique opportunity to issue an "open call" to all her creative admirers.

The commission? To create your own version of Girl with a Pearl Earring, for a chance to show your art in the Vermeer room at the Mauritshuis.

The rules? Well, there aren't many, in fact. Feel free to surprise us. A self-portrait in a bath towel turban, a painted iron or even a pile of dishes: more or less anything goes. Since nearly everyone knows the painting, the Girl is easy to recognised. The distinctive colours, shapes, and Vermeer’s typical use of light: before you know it, she has been conjured before you.

Vermeer's House: Hans Slager Rebufs Frans Grijzenhout's Rrecent Claims about the Location of Johannes Vermeer's House

Vermeer's House Again and the Jesuit Church

http://www.essentialvermeer.com/misc/SLAGER-VermeersHouseAgainandtheJesuit%20Church.pdf

October, 2024

In his article "Vermeer's House Again and the Jesuit Church," Hans Slager critiques Frans Grijzenhout's recent claims about the location of Johannes Vermeer's house (published in "Finding Vermeer, Back to the Molenpoort") and the hidden Jesuit church in Delft. Grijzenhout relies on a 1674 taxation ledger to place Vermeer’s residence at the eastern corner of the Molenpoort, but Slager argues that this method is flawed due to the many unknowns, guesswork, and incomplete research. Instead, Slager maintains his previously reasoned likelihood that Vermeer lived on the western corner of the Molenpoort, in a house called Trapmolen. He emphasizes that there is no solid proof for Grijzenhout's theory and critiques his reliance on assumptions.

Furthermore, Grijzenhout's analysis of the Jesuit church's location on the Oude Langendijk is also challenged. Slager contends that Grijzenhout misinterprets historical documents and overlooks key archival data. Grijzenhout suggests the church was located in the second and third houses east of the Molenpoort, while Slager maintains that it was in the fourth and fifth house, supported by schematic reconstructions and archival data.

If you prefer, you can click here to view the PDF in a new tab.

A Pulldown Database of Johannes Vermeer's Artistic, Social, and Personal Interactions

This interactive study is an exploration of the diverse and interconnected relationships that Johannes Vermeer maintained throughout his life with his professional, private mileau, and broader cultural setting. To illustrate these relationships, a list has been developed of individuals who may have come into contact, influenced, or been influenced by Vermeer, whether directly, or indirectly. This includes painters, clients, relatives, amateur scientists, writers, men of culture, as well as civic and religious officials.

Each entry is accompanied by an essential discourse on the individual's contributions or relevance in their respective fields, followed by their specific interactions or connections with Vermeer. The latter is indicated by an icon of Vermeer's signature.

Frans Grijzenhout Revises the Location of Vermeer's House

"Finding Vermeer"

by Frans Grijzenhout

April, 2024

Art historians, historiographers, and archive researchers have long debated the precise location where Vermeer resided with his family in a house rented by his mother-in-law, Maria Thins, in the Papenhoek (Papists’ Corner) area of Delft, where Vermeer presumably painted for most of his career. Was it the house called Groot Serpent on the eastern corner of Oude Langendijk and Molenpoort, or Trapmolen, on the western corner?

Over the past several decades, art history literature, following the archivist A.J.J.M. van Peer’s lead, has virtually without exception asserted that it was the large Groot Serpent. However, archival researcher Hans Slager has recently submitted that Vermeer and his family family actually lived in the smaller Trapmolen. This location was embraced by Pieter Roelefs in the catalogue of the Rijksmuseum Vermeer retrospective of 2023.

However, Frans Grijzenhout, art historian of the Early Modern Period, now presents an archival source that has not yet been included in the debate on the location of Vermeer's house, overturning Slager's claim. Moreover, Grijzenhout brings forward arguments to establish the exact location on Oude Langendijk of the Jesuit church, a significnat landmark for Delft's Catholic community as well as for Vermeer and his family.

Essential Vermeer goes YouTube!

After months of struggling to squash the formidable learning curve of producing video content, I've launched my latest intuitive: YouTube channel called My Take!: Vermeer’s Paintings One by One.

So why on earth did it ever come to this? Well, in the last twenty years I’ve done my very best to present the most thorough and balanced view of Vermeer’s art on the Essential Vermeer capitalizing on the immense and largely unexplored potential of the internet in regards to art historical issues. One of my top priorities has been objectivity. However, in recent years I've felt a growing need to communicate my own thoughts and feelings tempered by years of experience as a painter and ordinary person in front of extraordinary art.

The most efficient and effective means to communicate highly personalized content of this type is, I believe, via the video. It has the added advantage of allowing me to express myself with absolute freedom while maintaining the boundaries between the contents Essential Vermeer website and my videos clearly demarked.

I’ve just uploaded the first two videos: one on the Girl with a Flute, which the National Gallery of Art has officially demoted, and the other, A Young Woman Seated at the Virginals in the New York Leiden Collection.

- My Take: Girl with a Pearl Earring

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2oU6FCr6K34 - My Take: Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window

https://youtu.be/15PJ_5WQECo - My Take: Young Woman Seated at the Virginals

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Otelenp40oA - My Take: Girl with a Flute

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67DFAYyvOE8

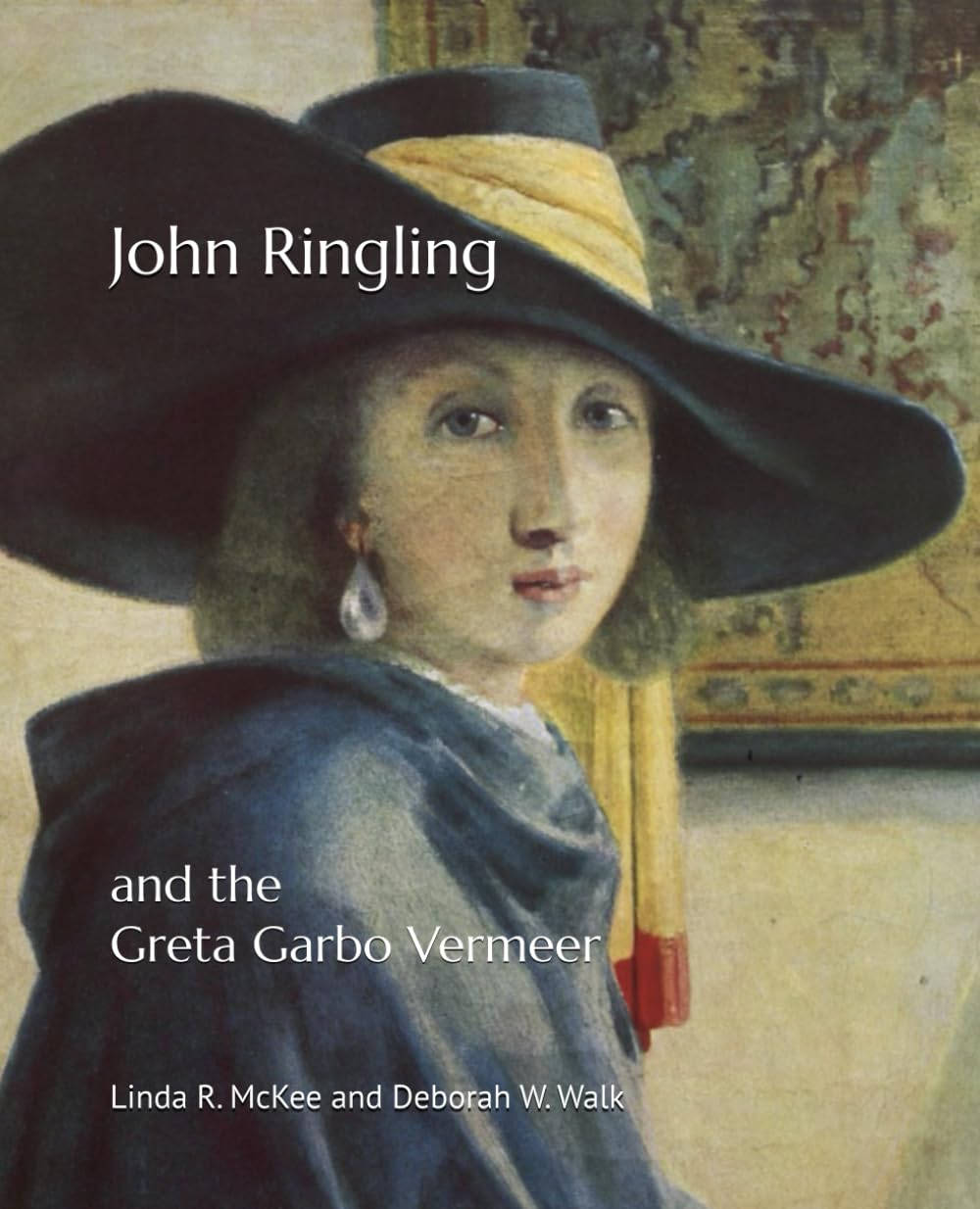

Vermeer-Related Publication: John Ringling and the Greta Garbo Vermeer

John Ringling and the Greta Garbo Vermeer

Linda R. McKee and Deborah W. Walk

August 17, 2024

https://amzn.to/4a1jTQ1

Linda R. McKee and Deborah W. Walk

John Ringling was one of the most prolific encyclopedic art collectors of the early twentieth century in America. Despite many purchases and acquisitions, his eponymous museum in Sarasota, Florida contained few written records of his art activities. This all changed in 1995 when The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art Archives received a treasure trove of German archival documents sent to them by Julius Böhler's nephew, Florian Eitle-Böhler. There was now secure evidence that Ringling was not only a collector, he was an investor and partner, working in close consort with his dealer Julius Wilhelm Böhler (1883-1966).

This book is a case study of the life of a painting that typifies much of the unpleasant side of the business of the international art world. The story is a result of serendipity, the author in 2008 reading Jonathan Lopez's book, The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van Meegeren, and discovering that Ringling himself was once the co-owner, not of a Van Meegeren, but of a well-known but poor Vermeer imitation, The Girl With the Blue Hat.

The Washington D. C: National Gallery of Art removes Vermeer's Girl with a Flute from display

Girl with a Flute, now attributed by the National Gallery of Art (NGA) to the "studio of Johannes Vermeer" rather than to the artist himself, is currently not on display. While the NGA has provided no future date for its return to view, the gallery explains that its temporary removal is due to the challenge of creating a balanced wall display and managing the limited space available to exhibit its collection.

In light of the NGA's reclassification, the decision not to display the painting may disadvantage both visitors and scholars who wish to evaluate and enjoy the painting, as it limits opportunities to engage with this debated work, especially considering that the work was for years hung next to Vermeer's Girl with a Red Hat and Woman Holding a Balance, and in close proximity to the Lady Writing. Displaying Girl with a Flute alongside the these Vermeer paintings would offer an invaluable chance for comparison and analysis, particularly given its historical inclusion in Vermeer's oeuvre. The reasoning behind the painting’s reattribution is detailed in the online publication "Vermeer’s Studio and the Girl with a Flute: New Findings from the National Gallery of Art," Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 14:2 (Summer 2022), authored by Marjorie E. Wieseman, Alexandra Libby, E. Melanie Gifford, and Dina Anchin.

Following the NGA publication, the Rijksmuseum displayed Girl with a Flute as an authentic Vermeer in its 2023 Vermeer retrospective. Jonathan Janson, founder of Essential Vermeer, has released a YouTube video defending the painting's authenticity, critically analyzing the NGA's claims and presenting arguments in support of its attribution to Vermeer.