The Trumpet in Vermeer's Painting

Although Vermeer's Art of Painting (fig. 1) is not considered a work with a musical theme, it nonetheless represents an important musical instrument of the time: the trumpet, an ancient instrument which held important symbolic meaning. According to the generally accepted interpretation, in Vermeer's painting, the artist is seen from behind, seated at his easel, painting a model who is dressed as Clio, the Muse of History. In Cesare Ripa's handbook Iconologia, available to Vermeer in a Dutch translation published in 1644 and certainly employed in the case of this painting, Clio is described as a girl with a crown of laurel, symbolizing Fame. She holds a trumpet and a volume of the Greek historian Thucydides, symbolizing History. The artist is dressed in a deliberately archaic, "historical" costume. Thus, Vermeer's meaning is that History should be the artist's inspiration. The young girl who daintily holds the instrument seems to tell us that she will "trumpet" the artist's work bringing fame not just to himself and his country but to his town as well. In Vermeer's case, as in a few other cases such as Leonardo da Vinci, Vermeer's own name has been indelibly linked to his birthplace, Delft.

A curious note is that in Vermeer's composition, the trumpet which the model holds could not be accommodated into the painting on the artist's canvas that sits on the easel judging by the drawing in light colored paint that can still be made out.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1668

Oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

History

The trumpet, one of the oldest instruments, is already mentioned in the Bible (the divine command to Moses: "'Make thee two trumpets of silver...," the "trumpets of Jericho" or the trumpets which shall sound on the Day of the Last Judgment). Its ancient precursors were widespread in Africa and Europe, less in Asia. They were made mainly from ivory, animal horns or shells (triton) or from shavings of tree bark. Long straight metal trumpets were used in the ancient Egyptian culture (called šnb) both for signaling but moreover as cult and symbolic instruments demonstrating the royal power of the Pharaohs (fig. 2).

Giuseppe Verdi has set these early trumpets an everlasting monument in his opera Aida requiring six long Egyptian trumpets, which were exclusively produced for the première (Kairo 1871) to his instructions and called then "Aida-trumpets."

of Tutankhamen, 1333–1323 B.C.

One is made of silver, the other of bronze. (Egyptian Museum, Cairo) [Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford].

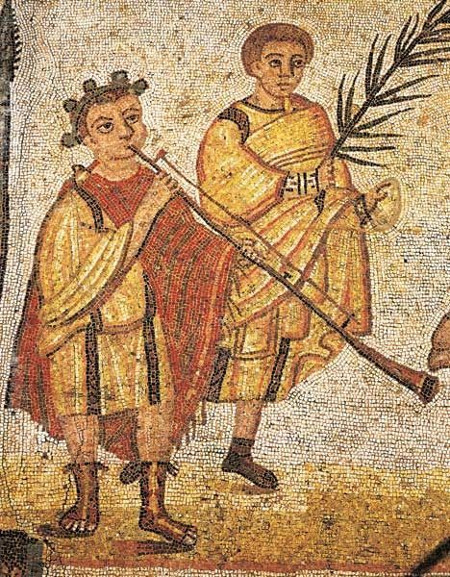

4th century

Sicilian floor-mosaic (21 x4 m.),

Piazza Armerina

This mosaic seems to show two heralds announcing the arrival of a king.

Similar functions of the instrument (fig. 3) like in the Egyptian culture are traced in the ancient Greek and Etrusco-Roman empire (called there Salpinx, Tuba, Lituus or Buccina) as well as in the Byzantine era.

After the fall of the Roman empire the trumpet disappeared from Europe and was not reintroduced until the Middle Ages, when during the Cursades it was taken from the Saracens as war booty and soon spread out across Europe. The trumpet's most important functions were both the military signaling in the battles and the marking of power and status, as only a king was allowed to have trumpeters at his court. In many parts of the world, trumpets and drums have been (and still are) part of the regalia associated with kingship. Renaissance sovereigns saw in their trumpet ensembles a symbol of their own importance. The Hungarian king Matthias Corvinus had 24 trumpeters at his court, and in 1482 there were 18 at the Sforza court in Milan. In 1548 the Emperor Charles V issued a decree putting trumpeters under the direct jurisdiction of the sovereign (fig. 4 & 5). From this time on the social status and distinction of the trumpeters differed more and more from that of the other court musicians.

Apart from the trumpet's official task there were many ways in which the trumpet was used to communicate. A short loud sound, series of sounds or rhythmic patterns served as a signal, a means of carrying a message or instruction over a great distance: For example, European herdsmen used alphorns to call each other across the mountains; Latvian youths played a goat-horn on summer evenings to announce their intention to marry; hunters blew their horns to ensure a successful hunt; and in Asia fishermen blew their conch-shell "trumpets" to summon assistance for bringing in their nets. But not all communication was pastoral. From the Roman legions to the US Cavalry today, trumpets have always been an essential part of military life.

In the early fifteenth century, the form of the trumpet developed from the long straight into a folded one; at first to an S-shape, then with this S-shape folded back on itself to a loop—a more compact arrangement that has since remained standard. In the sixteenth century, Nuremberg became the great center of brass-instrument making and remained so throughout the Baroque period. The members of the Neuschel and Schnitzer (fig. 6) families were the earliest Nuremberg brass-instrument makers.

Nikolaus Hogenberg

c. 1530

Etching on paper. 35.7x 30.2 cm.

Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel

Nikolaus Hogenberg

c. 1530

Etching on paper. 35.7x 30.2 cm.

Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel

Wien

Sammlung alter Musikinstrumente [Collection of early musical instruments]

by Jacob Steiger, Basel 1578.

Basel, Historisches Museum.

Few extant sixteenth-century instruments have survived, such as two city trumpets made in 1578 by Jacob Steiger of Basle (fig. 7).

The leading English makers of that time were William Bull, John Harris and, later, William Shaw.

The trumpet's compass was extended upwards as far as the 13th partial (= harmonic). Within the trumpet-kettledrum ensemble certain players became responsible for specific registers. A five-part ensemble consisted of players capable of playing certain scales of notes. Cesare Bendinelli in his method of 1614 gave specific directions for improvising the upper parts in such a five-part ensemble. This music had a distinctive style, probably going back to the Middle Ages: over a drone of tonic and dominant the upper three parts weave their counterpoint.

In 1623, the Emperor Ferdinand II granted an Imperial Privilege to found the Imperial Guild of Trumpeters and Kettledrummers. The Elector of Saxony was named patron of the guild and arbiter of its disputes. The articles of the guild were subsequently confirmed by every Holy Roman Emperor up to Joseph II (1767). The guild had two main functions: to regulate instructions and thus limit the number of trumpeters, and to ensure the trumpet's exclusiveness by restricting where it could be played and by whom. Although the organization of trumpeters into such a guild of more than just local importance was unique to the Holy Roman Empire, the trumpet enjoyed a similar status in other European countries. Following this great example the Nuremberg brass-makers formed a guild of their own in 1635, which was closely supervised by the council.

From the end of the sixteenth century on the trumpet was gradually accepted as an instrument for "art music." The medieval "tournaments" developed into more stylized "carousels" or equestrian ballets, in which costumed participants formed intricate figures. These ballets required a more artistic musical accompaniment, but since the music of the court trumpet corps was often improvised, only few examples have survived.

In the seventeenth century the five-part trumpet choir at the Habsburg court was a symbol both of the ecclesia militans and the imperial power. The court composers integrated the trumpet choir as a unit into vocal compositions, like masses, magnificats or Vespers psalms. Many famous musician-composers of that time, like Johann Heinrich Schmelzer (c. 1620/23–1680), Heinrich I. F. Biber (1644–1704) or Johann Joseph Fux (1660–1741) wrote large-scale Messe con trombe. Praetorius in his choral setting of In dulci jubilo (1619) used a six-part trumpet ensemble. Heinrich Schütz's Buccinate in neomenia tuba of 1629 was probably the first piece to include a c'' (16th partial) for trumpet.

During the seventeenth century two styles of trumpet playing developed: the "Feldstück," or "Prinzipalblasen," and the "Clarinblasen." The first, named in the King James Bible as "blowing an alarm" or "blowing" was appropriate for military signals and for the "outdoor" music of the trumpet corps. The second, softer style was associated with solo playing in the clarino (high) register. This style required a refined blowing technique and virtuosity on the instrument. Therefore the "chamber" or "concert" trumpeters increasingly distinguished themselves from the other members of the corps and were spared the weekly playing at table not to spoil their subtle "embouchure" [shaping of the lips to the mouthpiece] necessary for clarino playing. Eighteenth-century theorists praised players who were able to play the trumpet as softly as a flute.

The most important center for Baroque trumpet playing was Vienna with the Habsburg court, followed by Dresden, Leipzig, the former Kremsier (Kromeríč), Bologna, London and, to a lesser extent, Paris. Vienna's elaborate court protocol prescribed precisely the use of trumpets on the highest feast days, sacred and secular (like the birth- and name days of the Emperor and Empress, at coronations and similar high ceremonies). On all these occasions the usual string orchestra was joined by one or even two choirs of trumpets, in groups of two high (clarini) and two low (trombe). In church music a tradition of "solemn sonatas" arose, replacing the sequence or, on highly ceremonial occasions, the gradual of the Holy Mass.

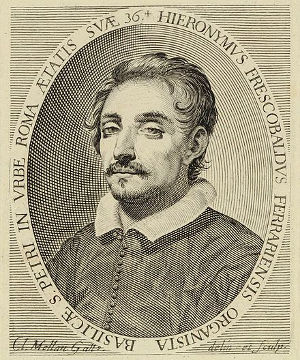

(1600–c. 1675)

In Kremsier, Pavel Josef Vejvanovský (c. 1633–1693), a court and field trumpeter, wrote and played numerous intricate sonatas. The Bologna composers Petronio Franceschini, Domenico Gabrielli and Giuseppe Torelli likewise wrote various trumpet parts and concerti of great virtuosity. But the most renowned Italian trumpeter was certainly Girolamo Fantini (1600-c. 1675) (fig. 8). In Rome 1634 he took part in the first known performance of a solo trumpet with keyboard accompaniment, played by Frescobaldi on Cardinal Borghese's house organ. In 1638 he published an important trumpet method: Modo per imparare a sonare di tromba including also the first known pieces for trumpet and continuo, among them eight sonatas specifically for trumpet and organ. Furthermore, Fantini extended the high register from the g'' and a'' up to c''' (and once to d'''). He was celebrated for his solo performances with his highly developed, specific blowing technique.

When Johann Sebastian Bach arrived 1723 in Leipzig he found an important tradition of trumpet playing, mainly from the "Town Waits," the well-known "Stadtpfeifer" (see also Don L. Smithers, Municipal Trumpeters and the Stadtpfeifer). Bach's predecessors as Kantors of the Thomaskirche had thought well of the instrument, and in 1675 Johann Christoph Pezel, both a trained "Stadtpfeifer" and appointed "Kunstgeiger" (Violinist) in Leipzig, had published six elaborate sonatas for two trumpets and continuo. Bach composed much (but not all) of his most splendid trumpet music for Gottfried Reiche, senior Stadtpfeifer until his death in 1734 and one of most outstanding virtuoso trumpet players of his time.

In England, it was above all Henry Purcell (1659–1695), one of the greatest of all English composers, who made use of the trumpet in various odes for chorus and orchestra, anthems, dramatic compositions and theatre interludes (sonatas) for the Royal court. Although George Frederick Handel was the last prominent "English" composer in the eighteenth century he wrote some of the most famous music for the trumpet, like the solo part in the aria The trumpet shall sound from the oratory Messiah or both the festive (and very popular) Firework- and Water-Music.

French trumpet music retained especially the heroic affect in the music for the theatre and ballets as well as in the sacred music. The préludes to the Te Deum-settings by Jean-Baptiste Lully and Marc-Antoine Charpentier are the most stirring and best-known examples.

The period between about 1720 and 1800 marked both the high point and the decline of the Baroque trumpet. The clarino playing technique was fully developed. Some of the latest concertos for solo Baroque trumpet were composed by Michael Haydn, Franz Xaver Richter and Leopold Mozart. Then the trumpet concerto became "out of fashion." New musical forms in a less pompous style preferred the violin, oboe and flute and did not use the trumpet in the old way. Furthermore, the decline of the courts, hastened by the French Revolution, diminished the employment for trumpet virtuosi (like many other musicians) and deprived the Imperial Guild of Trumpeters and Kettledrummers of its socio-economic foundation. The guild was finally dissolved in Prussia in 1810; and 1831 in Saxony.

Nevertheless, the trumpet continued to play an important role in the brass section of the large symphony orchestras as well as in the military music corps playing on all official state ceremonies up to our days.

Municipal Trumpeters and the "Stadtpfeifer"

by Don L. Smithers

Of the many perils against which medieval Europe had to defend itself two were especially harmful to municipal life: (a) hostile and invading forces from without; (b) the danger of fire from within. To facilitate easier and more reliable observation of both kinds of danger most cities built central towers within the city and high observation towers above the main gates of the surrounding walls. – In smaller towns the approach of the enemy or the discovery of fire was easily communicated to the populace by the tolling of a bell, either one in a centrally located church or one mounted in the town square. In the larger cities information was communicated to the bell ringers by means of horns or trumpets, specially provided for the purpose of sounding alarms and signalling the completion of a round by the watchman of a particular sector.

As the medieval towns and cities of Europe came to rely more and more on the sounding of trumpets and like instruments for the warning of fire, rules had to be made to prevent false alarms or the possible misinterpretation of unofficial trumpet playing. As early as 1372 the Paris police regulations made unofficial trumpet blowing a crime after the hour of curfew—except at weddings.

From their initial function as civic security guards the trumpet playing Feuerwächter [fire waits] and town waits eventually became the municipal musicians, known at various times and places as "speyllieden," "piffari," "stadspijpers," and especially in Central Europe, usually known as the Stadtpfeifer (municipal piper). The most important areas to develop municipal music and musicians were the Central European Germanic principalities of the Holy Roman Empire. As their duties became more formalized and their quasi-military capacity acquired greater ceremony (e.g. mounting the watch, changing the night watch) the function of Central European Türmer changed [Germ. "Turm" = tower; Türmer = the man watching on a tower]. What was at first a necessary and utilitarian occupation became a ceremonious and decorative adjunct of civic life. With a gradual development of their musical skills the Türmer spent less time fire watching and more time providing musical entertainment at official city proceedings. A tradition was rapidly established, and in some areas the town musicians banded together into a "bruederschappe" or "Bruderschaft" (brotherhood). –

But irrespective of the fame and excellence of musicians in many German towns and cities, it was the art of the Saxon Stadtpfeifer at Leipzig that was truly remarkable. Nowhere else in Europe did the title of Stadt-Musicus have greater significance and musical importance than at Leipzig. – The Leipzig Stadtpfeifer were not only required to be excellent performers and to provide suitable music each day (the daily Abblasen [playing of chorals in the evening] from a balcony on the town hall was begun in 1599), but many were also accomplished composers.

:

Don L. Smithers, The Music and History of the Baroque Trumpet, 2nd ed., Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale and Edwardsville 1988, 116–123.

Structure

(a) Natural trumpet, mid-18th century

(b) modern fanfare trumpet;

(c) English slide trumpet, c.1850

(d) keyed trumpet, c.1820;

(e) Inventionstrompete, 1826

(f) valve trumpet in G, c.1865;

(g) valve trumpet in G, with Vienna valves, c1850 [E. H. Tarr].

In the following the focus is laid on the natural (fig. 9) or Baroque trumpet.

The form of the natural trumpet which had been developed in the late Middle Ages (see "History") was a twice folded or closed S-shape with a bell-shaped flare of exact mathematical proportions. This form, which persisted until today, makes the instrument not only more convenient to hold but also, with a thick cord wound around the two adjacent sections, a stronger, more durable one.

A "normal" Baroque trumpet had a length between 7 and 8 feet and was made of metal (usually copper, bronze or brass). Fanfare or herald trumpets, required rather for state occasions, were often made of silver, decorated with gold leaf.

The two reverse bends, called "bows," are joined to the three straight sections, the "yards," by short connectors, called "ferrule." The mouthpiece, as the supporting sound generator, is inserted into the first yard, followed by the first bow, which continues the bore back to the second yard of exactly the same length as the first and usually below and parallel to it. The second yard joins the second bow, also connected with a ferrule, turning the bore into the final yard-bell section. The third yard, usually half the length of the first and second, is fitted to the expanding bell section. The joint of the two sections is concealed under a tightly fitted cover which in the Baroque period had a ball-shaped decoration surrounding it. This ball, called the "boss," is not a merely decorative element, but served as a grip to hold the instrument. Another "functional decoration" is the "garland," a band of metal that overlays the bell to strengthen it and serving as the main element of decoration where the maker's sign or name is usually found.

On the Baroque trumpet, the vent holes are located at the top of the second yard, and possibly on the second bow.

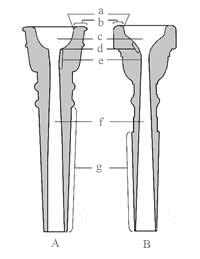

Baroque and modern trumpet mouthpieces

a – inner edge of rim, or 'bite',

b – rim facing,

c – cup

d – sharp edge (A) or shoulder (B)

e – throat or bore

f – backbore

g – shank

The mouthpiece (fig. 10) has two tasks: to support and contain the vibrating membrane, i.e. the player's lips, and to produce a complementary edge-tone. The latter is of particular importance for the sound-production of a trumpet as it depends on the frequencies of the vibrating lips reinforced by the mouthpiece's edge-tone and the available notes of the air column. So the sound-production works with a three-part coupled acoustical system, but this does not entirely explain the difference in timbre from one instrument to another and the characteristic tone of the Baroque trumpet. This difference which we can hear has its reason in the free vibrations of the instrument itself caused by the energy of a produced note. When the high frequencies of the instrument coincide with the harmonics of various notes the free vibrations reinforce the coincident harmonics and this marks the special quality of a particular instrumental timbre—whether of a trumpet, a violin or an organ pipe.

The mouthpiece, then, must be proportionate to the total length of the air column and must be designed to aid the production of particular frequencies. That's why Baroque trumpet mouthpieces were generally constructed in two or three specific sizes. A shallow "bowl" or cup assists the production of the high frequencies; a bowl of medium depth is for the middle register, and the deep one is for the lowest frequencies. At the bottom of the cup is the edge-tone-producing "throat," which communicates with an expanding backbore. To enhance the production of high notes, Baroque mouthpieces had a "shoulder" or grain (the point where the bowl and throat intersect) with a very sharp angle. This abrupt transition from the bowl to the throat facilitates the production of high-frequency edge-tones which in turn support the playing of the highest registers (clarino).

Playing Technique

The natural trumpet is able to produce only the notes of the harmonic series. The sound of the trumpet is generally produced by blowing air through closed lips so as to produce a "buzzing" effect through vibration with the support of the mouthpiece. This creates a standing wave of vibrating air and metal in the trumpet. The player can select the pitch from a range of harmonic series (partials) or overtones through altering the amount of muscular contraction in the lip formation. Therefore he or she has do develop an efficient, subtle "embouchure" (French: "la bouche" = the mouth). The performer's use of the air as well as tongue manipulation can affect how the embouchure works. The famous trumpet player Girolamo Fantini was the first to demonstrate, that by playing in the extreme upper register and "lipping" the notes of the 11th and 13th partials (flattening or sharpening those impure harmonics into tune with the embouchure) it was possible to play diatonic major and minor scales (and, hence, complete melodies). Virtuoso professional players were even able to produce certain chromatic notes outside the harmonic series by this process of "lipping" (such as natural C down to B), although these notes were mostly used as brief passing tones in the period compositions.

The harmonic series contains higher notes that are slightly out of tune and need correction. This means that the strength of breath must be carefully controlled. Playing in tune was perhaps the most important prerequisite for the acceptance of the trumpet into ensembles of strings in the seventeenth century.

Iconographic Meaning

In the Renaissance period the trumpet, as a typical instrument of fame and glory with its loud, metallic but likewise "festive" sound, appears, like many other instruments, in the large angelic consorts. There it is played for the celestial "Glory to God in the Highest." Well-known examples are the Festive Coronation of Saint Mary (c. 1435) (fig. 11) by Fra Angelico showing eight long straight trumpets—or the triptych Christus omgeven van zingende en musicerende engelen (Christ Surrounded by Musician Angel) by the Flemish master Hans Memling (1480). It shows the usual combination of wind instruments with various forms of trumpets and a shawm (fig. 12).

Fig. 11 Festive Coronation of St. Mary (detail)

Fig. 11 Festive Coronation of St. Mary (detail)Fra Angelico

c. 1435

Tempera on panel, 112 x 114 cm.

Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi

Hans Memling

1480s

Oil on wood, 165 x 230 cm. (each panel)

Antwerpen, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten

Details from the left and right panel.

(left panel: from left to right: a twice-folded trumpet and a shawm, (right panel: from right to left: a folded and a long straight trumpet).

The rather profane task of the trumpet as the main instrument for outdoor communication is the blowing of the various signals in war (fig. 13) or calling attention on official proclamations, but likewise "signaling" the arrival of a king or even the pope. Such large, festive processions appears often in large tapestries or successions of colorful woodcuts or paintings.

Power and status can also be marked in other contexts. There is often an association between trumpets and gender difference. Though trumpets are loud instruments reserved for outdoor use, the separation between male-dominated public and female-dominated private domains is equally widespread. This applies to the traditional associations with regalia, signaling and ritual, all of which mediate with the outside world thus fall into the public domain controlled, in most cultures, by men.

Trumpet Sources:

- Grove Music Online http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/

entry "Trumpet": Margaret Sarkissian, Edward H. Tarr - Don L. Smithers, The Music and History of the Baroque Trumpet before 1721,

Carbondale and Edwardsville, 2nd ed. 1988. - Erich Höhne, Musik in der Kunst, 2nd ed., Leipzig 1973.

The Trumpet on the Web:

- The Natural Trumpet Resource Web Site:

http://www.earlybrass.com/nattrump.htm - International Trumpet Guild:

https://www.trumpetguild.org/