Education

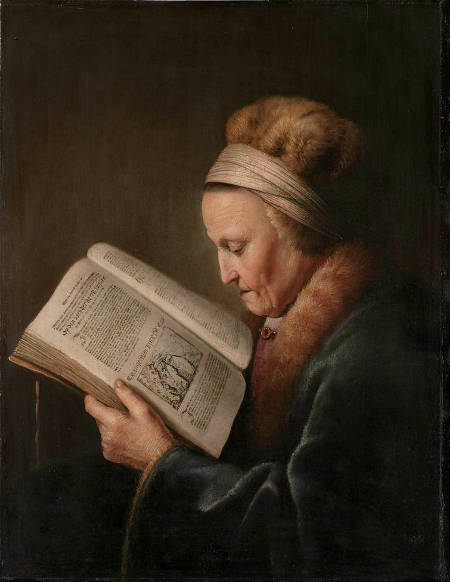

Gerrit Dou

c. 1630

Oil on wood, 71 x 55.5 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Netherlands valued education due in part to the Protestant Reformation's emphasis on individual Bible reading (fig. 1). This cultural focus led to higher literacy rates among women compared to other European societies. Education enabled women to manage businesses, engage in intellectual pursuits, and participate more fully in social and economic life. In 1630, 57 percent of Amsterdam’s bridegrooms and thirty-percent of brides were able to sign their marriage certificates; by 1680, the numbers had risen to seventy percent of men and forty-four percent of women. While the percentage for Dutch women was lower than for Dutch men, scholars agree that literacy for women in the Netherlands surpassed that of any other European nation.

The inclusion of girls distinguished the schools of the United Provinces and, it could be argued, propelled the country toward its Golden Age prosperity by equipping a corps of literate, savvy female citizens to build their futures in the New World. Girls were given the chance—as a right rather than a luxury—to learn the same fundamental skills as their brothers: reading, writing, and arithmetic, which they would need to make successful lives alongside the men of the Dutch Republic. Although no higher education was available for girls or women and would not be for hundreds of years, the academic opportunity offered by the United Provinces was extraordinary for its time. Holland was the sole nation in seventeenth-century Europe to provide primary education to girls as a matter of course.

Schools and literacy in the 17th-century Netherlands were distinctive compared to much of the rest of Europe at the time, reflecting the Dutch Republic's broader emphasis on civic responsibility, religion, and economic prosperity. Education was more widespread in the Netherlands than almost anywhere else in Europe, and literacy rates were relatively high, although they still varied by region, gender, and social class.

Schools for children were typically divided into a few different types. Most towns had basic primary schools, often referred to as "elementary" or "petty" schools, where children learned to read, write, and do simple arithmetic. Reading instruction often came first and was heavily tied to religious education; children would learn their letters and then move on to read the Bible or the Calvinist catechism. Writing and arithmetic were sometimes considered additional subjects, requiring separate instruction and sometimes extra payment. Teachers were usually modestly trained themselves, and schools were often funded by local municipalities or churches. In Protestant areas, which included most of the Dutch Republic, schooling was seen as part of a religious duty: individuals needed to read Scripture themselves to live a righteous life, making basic literacy an important social value.

Quiringh van Brekelenkam

1660

Oil on panel, 46 x 37 cm

Private collection

For children from wealthier families, there were Latin schools, which provided a more rigorous education intended to prepare boys for university study or professional careers in fields such as law, medicine, or theology. Instruction in Latin schools was classical and humanistic, focusing on Latin grammar, rhetoric, logic, and sometimes Greek. These schools were generally for boys, though a few exceptional girls from wealthy or scholarly families might receive private instruction.

Girls' education tended to be more limited in scope. Girls were usually taught to read, often at home or in church-affiliated schools, but writing was less emphasized for them than for boys. Sewing schools were common for girls, combining basic reading with practical training in needlework, skills considered essential for managing a household. Nevertheless, there are many examples of women who could read fluently and some who maintained correspondence or engaged in family businesses, suggesting that functional literacy among women was more widespread than formal schooling records might suggest.

Literacy rates in the Dutch Republic during the 17th century were significantly higher than in most parts of Europe. Estimates suggest that by the mid-17th century, between 40% and 60% of adult men could read, with lower but still notable rates for women. In cities like Amsterdam, Haarlem, and Leiden, rates were even higher. This general literacy contributed to the flourishing of a lively print culture, including newspapers, pamphlets, religious tracts, maps, and popular literature, much of which was affordable enough to reach a broad audience.

The strong tradition of literacy also influenced the arts. Paintings sometimes include depictions of people reading or writing letters, as seen in many works by Vermeer, where female figures are portrayed holding letters, pens, or books with a sense of dignity and inward reflection. Gerard ter Borch (1617–1681) similarly painted many scenes involving letter writing and reading, imbuing these quiet acts with emotional depth and a suggestion of personal autonomy. These recurring themes reflect not only personal narratives but also a broader cultural respect for literacy as a mark of civility, discipline, and moral uprightness.

There are nummerous paintings from the 17th-century Netherlands that depict children learning to read or write in domestic settings, reflecting the growing value placed on literacy within the home. Paintings by artists like Vermeer and Gerard ter Borch (1617–1681) often show individual children or young women engaged in writing letters or reading, usually in a quiet, private interior. These works emphasize literacy as a personal and familial virtue, tied to discipline, refinement, and moral upbringing.

Jan Steen (1626–1679)

c.1665

Oil on canvas, 110.5 x 80.2 cm.

National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

At the same time, there are also paintings that portray actual schools with multiple students, providing a view of more communal education. The most notable examples often show small, somewhat informal schoolrooms rather than large institutional spaces. Jan Steen (c.1626–1679) painted several lively school scenes, such as The Village School and The Schoolmaster Punished, where children are gathered together under the sometimes chaotic supervision of a teacher. In Steen’s characteristic style, these scenes are often humorous and satirical, showing the unruliness of children and the difficulty of maintaining discipline, which may also reflect contemporary concerns about the challenges of educating youth.

Steen's lively, often chaotic depictions of daily life are clearly part of a broader Northern tradition that Bruegel had helped to shape in the 16th century. Bruegel was known for his bustling village scenes, filled with unruly crowds, mischief, and a strong sense of human folly. His paintings often carried a moral lesson, but they were presented through scenes that combined humor, disorder, and a very physical, animated style of storytelling.

In The Schoolmaster Punished, Steen portrays a moment of topsy-turvy justice where children, often the objects of discipline, take playful revenge on their hapless teacher. The composition is filled with bustling figures, a slightly exaggerated sense of movement, and an atmosphere of comic anarchy—all features that resonate with Bruegel’s approach. Like Bruegel, Steen uses humor to expose human weakness, but he shifts the tone slightly to fit the more bourgeois, domestic world of 17th-century Holland, moving away from Bruegel’s more rustic, peasant subjects. Jan Steen's A School for Boys and Girls is in the satirical tradition of Pieter Bruegel the Elder's print The Ass at School which illustrates a popular saying: "Though an ass goes to school in order to learn, he'll still be an ass, not a horse, when he returns." In Steen's school there is little to be learnt from the short-sighted teacher who is so intent on sharpening his quill that he fails to notice the chaos around him. Some children who are keen to learn have gathered around the schoolmistress who corrects their spelling but others fight, sing, make fun of the teachers and even sleep. On the right a child hands a pair of spectacles to an owl, a familiar symbol of foolishness in Steen's work.

Jan Steen

c. 1670

Oil on canvas, 83,8 x 109,2

National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

The influence of Bruegel on Steen is not a matter of direct imitation but rather of a shared cultural inheritance. Both artists used scenes of ordinary life to comment, sometimes slyly, on human behavior, social norms, and the frailties of discipline and authority. Steen, however, adapted the Bruegelian spirit to the conditions of his own time, focusing more often on middle-class domesticity and town life rather than the rougher village settings of Bruegel’s world.

Other artists, such as Cornelis Saftleven (c.1607–1681), also depicted school interiors. These paintings typically show modest rooms filled with simple benches and desks, with students of varying ages learning to read, write, or recite lessons. Teachers are often portrayed with a rod or stick, suggesting that corporal punishment was a normal part of maintaining order in the classroom.

These depictions confirm that schooling was seen as an important, if not always easy, undertaking. They also suggest that while private, home-based literacy was highly valued, there was a strong presence of communal education in towns and villages. These school scenes often contrast the ideal of disciplined learning with the reality of noisy, unruly students, providing a vivid glimpse into the everyday life of the Dutch Republic.

In the seventeenth century, it became increasingly common for the sons of the Dutch elite to embark on the "Grand Tour" to France and Italy, where they observed the rules of civility practiced by the French and Italian upper classes. Simultaneously, daughters of the Dutch upper classes attended "French schools" to receive a general cultural education, including learning French and being instructed in the rules of civility and courtesy. Education in manners and etiquette was also provided by private instructors, dancing masters, and parents.An illustrative example is the education that Contantijn Huygens (1596–1687) received from his father Constantijn Sr., who had served as a secretary at the court of William of Orange from 1578 to 1584. Having observed the manners appropriate for young people of rank, he decided to teach these behaviors to his own children. The lessons included the complexities of greeting and leave-taking rituals, such as covering and uncovering the head, offering hands, bowing, and specific movements. He emphasized the importance of his children being able to interact confidently and exemplarily with people of higher rank, ensuring they observed the standards of civility and due respect without undue nervousness.

The inclusion of girls distinguished the schools of the United Provinces and, it could be argued, propelled the country toward its Golden Age prosperity by equipping a corps of literate, savvy female citizens to build their futures in the New World. Girls were given the chance—as a right rather than a luxury—to learn the same fundamental skills as their brothers: reading (fig. 2 &3) , writing, and arithmetic, which they would need to make successful lives alongside the men of the Dutch Republic. Although no higher education was available for girls or women, nor would it be for hundreds of years, the academic opportunity the United Provinces offered its female citizens was extraordinary for its time. Holland was the sole nation in seventeenth-century Europe to offer girls primary education as a matter of course.

Gabriel Metsu

c. 1653–54

Oil on canvas, 105 x 90.7 cm.

Leiden Collection, New York

Pieter Janssens Elinga

c. 1668/70

Oil on canvas, 75.5 x 63.5 cm.

Alte Pinakothek, Munich

The core curriculum in Holland’s primary schools remained essentially the same for both sexes. James Howell (c. 1594–1666), an English visitor to Amsterdam, described the autonomy that resulted from the superior education Dutch girls received. Women were expert "in all sorts of languages," he wrote in a 1622 letter. "In Holland, the wives are so well versed in Bargaining, Cyphering, & Writing, that in the Absence of their Husbands in long sea voyages they beat the Trade at home & their Words will pass in equal Credit." He also noted that schools were well-organized, and both boys and girls had access to education. The emphasis on reading and writing among children was apparent, and Howell attributed this to the general prosperity and practical mindset of the Dutch population. He observed that even people from modest backgrounds could read. Today, scholars agree that literacy for women in the Netherlands surpassed that of any other European nation.

The Dutch Reformed Church prescribed equality for women. While it shared some scriptural elements with Puritans and other Protestant denominations, it differed significantly in its teachings regarding men and women, advocating mutual respect rather than wifely submission to a husband and suggesting that companionship, or gemeenschap, constituted a primary reason for marriage. According to the church, a proper wedded relationship featured the husband as the literal head of the household, but he was required to demonstrate his worthiness for that role by accepting household management as his wife’s responsibility and treating her with respect. Calvinist doctrine even emphasized the importance of physical affection as the foundation for a godly union, with marital intimacy described as the "godly mortar" for a marriage (physical satisfaction was seen as essential for both spouses, according to church teachings).

Nonetheless, higher education institutions like universities were almost exclusively male domains, and there was an ingrained belief that intellectual pursuits were not suitable for women. Universities at that time, such as those in Leiden and Utrecht, were intended for preparing young men for professions like law, theology, and medicine. These fields were thought to require a level of abstract reasoning and public engagement that many believed women were either not suited for or not meant to pursue. However, there were exceptions—some women from wealthy or intellectual families were educated at home to a very high level. These women sometimes corresponded with scholars or were involved in intellectual circles.

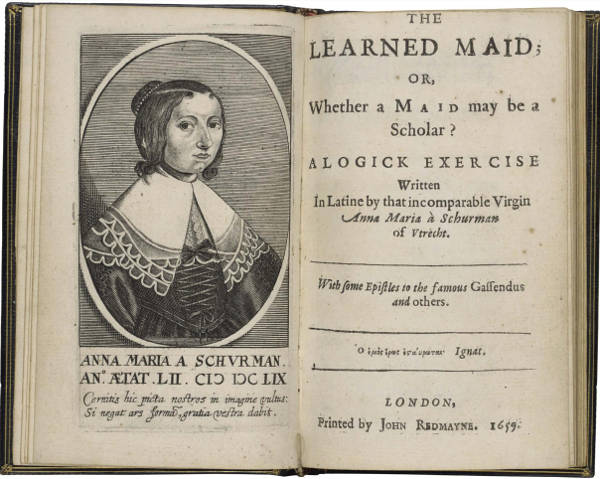

A few notable women managed to gain recognition for their learning, but they were anomalies rather than the norm. Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–1678 (fig. 4), for instance, was an exception who attended lectures at the University of Utrecht in the seventeenth century, though she did so from behind a curtain, as she was not formally admitted as a student. She was highly accomplished in languages, theology, and philosophy, demonstrating that some women managed to access higher education despite societal constraints. However, her experience was the exception rather than the rule, highlighting the limited opportunities available to women in formal academia during that period.

Anna Maria van Schurman

Printed in Latin as Dissertatio de Ingenii Muliebris ad Doctrinam et meliores Litteras Aptitudine

1641, Utrecht

In her time, Van Schurman was a renowned scholar, artist, poet, and early advocate for women’s education. Known for her exceptional intellect and mastery in numerous fields, Schurman was highly skilled in art, music, and literature, and was proficient in fourteen languages, including Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and Arabic. She was one of the most learned women of her time and became the first woman to attend a Dutch university, where she sat behind a screen to maintain propriety in male-dominated lectures. Her works and correspondence highlighted her belief in women's right to education, which she defended in her 1641 treatise, The Learned Maid.The Learned Maid; or, Whether a Maid may be a Scholar? by Anna Maria van Schurman is a groundbreaking 17th-century treatise advocating for women's right to education. Published in 1641, it argues logically for the intellectual equality of women, countering societal beliefs that restricted their scholarly pursuits. Van Schurman contends that women have the same rational abilities as men and should therefore have access to learning. An accomplished scholar herself, she modeled her beliefs, mastering numerous languages and attending lectures at Utrecht University, though separated by a screen. Her work is a foundational text in feminist thought, championing intellectual freedom and equality for women.

Van Schurman was born in Cologne to wealthy parents and demonstrated intellectual talents from an early age. She quickly mastered various arts, such as embroidery, paper cutting, and wax sculpting, and was also accomplished in calligraphy and engraving. Under her father's encouragement, she studied classical languages alongside her brothers—an uncommon practice at the time. Van Schurman maintained extensive correspondence with intellectuals across Europe, fostering connections with figures such as Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687), Friedrich Spanheim (1600–1649) , and Gisbertus Voetius (1589–1676). By the 1630s, her home in Utrecht had become a gathering place for scholars and artists.

In her thirties, Van Schurman was granted honorary admission to the prestigious St. Luke Guild of painters. She explored various artistic forms, including engraving on glass and wood, and was celebrated for her skillful and delicate engravings. Her artistry, combined with her intellectual accomplishments, earned her a prominent reputation and the title "Star of Utrecht." Despite societal expectations, she maintained a commitment to celibacy, choosing to dedicate herself to her studies and faith, famously adopting the motto, Amor Meus Crucifixus Est ("My Love Has Been Crucified").

Later in life, Van Schurman became a leading figure in the Labadist movement, a religious community that valued asceticism and a separation from secular society. She wrote extensively on her disillusionment with the Reformed Church, calling for spiritual renewal and advocating a life of devotion. Her final years were spent in relative isolation within the Labadist community, where she continued to write and correspond, solidifying her legacy as a pioneer of women's intellectual and spiritual independence.

Religion

In the seventeenth-century Netherlands, women's lives were deeply influenced by religion, especially within the context of the Calvinist Reformed Church, which dominated much of Dutch religious life. Protestant values held that the family was a cornerstone of piety, and women were seen as central to fostering religious devotion within the household (fig. 5 & 6). As mothers, they were expected to teach prayers, Bible stories, and core doctrines to their children, laying the foundation for a devout upbringing. This role was part of a broader expectation that women would instill moral values in their children, ensuring the continuity of Calvinist faith across generations.

Public worship, too, offered a structured space for women's involvement, even though it maintained a clear separation between men and women during services. Calvinist worship was stripped of elaborate rituals and focused intensely on preaching, with women participating through attendance, hymn singing, and prayer. Though barred from holding formal positions of authority within the church, women’s active engagement in congregational life was seen as crucial to the religious fabric of their communities.

In addition to worship, women's piety was reflected through charitable works, which were a cornerstone of Calvinist ethics. Many women were involved in social and charitable activities, caring for the sick, aiding the poor, and contributing to the upkeep of orphanages. Informal religious groups, such as prayer circles and charitable societies, also emerged as spaces where women could exercise a degree of independence in their religious lives while supporting their community’s moral welfare.

For Catholic women, especially those in the southern provinces and urban centers like Amsterdam and Utrecht, religious life was markedly different. Although Calvinist authorities controlled the Netherlands and placed restrictions on Catholic practices, Catholicism endured, with some convents continuing to function discreetly. While fewer women were able to join convents than before, those who did found a life of quiet devotion in these regulated spaces, maintaining a tradition of cloistered worship even under Protestant rule.

The Netherlands was also home to smaller religious communities, such as the Mennonites, who embraced a more egalitarian approach to family and community life. Mennonite women often had a more active role within their religious communities than was common in Calvinist or Catholic circles, sometimes leading small groups and contributing to communal decisions, reflecting the Mennonites' decentralized, community-oriented faith.

Religious art and iconography of the time also played a subtle but significant role in shaping women's religious ideals. Though Calvinism discouraged the use of religious imagery within churches, many households contained devotional prints or emblematic books that depicted female saints, biblical heroines, or personifications of virtues like chastity and charity. These images provided moral guides, reinforcing ideals of piety, devotion, and modesty.

The Dutch Republic was renowned for its religious tolerance and freedom of the press, becoming a haven for radical religious movements such as the Quakers, Labadists, Hebrews, and other dissenting groups. Women figured prominently in these movements, both as leaders and adherents, actively propagating their ideas and attracting followers across genders. However, representatives of the Reformed Church heavily criticized these groups, often targeting women in their critiques. Contemporary sources, including poems, pamphlets, tracts, printed images, and paintings, frequently depicted women in these movements, reflecting societal anxieties about female participation in religious dissent.

Quiringh van Brekelenkam

Oil on panel, 26 x 35 cm.

Private collection

Willem de Poorter

First half of 17th century

Oil on panel, 34 x 31 cm.

Private collection

In the realm of convent life, women contributed to the writing and dissemination of vernacular sermons. Although preaching was reserved for men, nuns played a crucial role in recording and editing sermons, thereby exercising influence over spiritual teachings. These activities not only provided spiritual guidance but also demonstrated women's intellectual capabilities and collaborative efforts within religious communities.