In 1689, fourteen years after Vermeer’s death, an ambitious travel guide titled Reis-Boek door de Vereenigde Nederlandtsche Provintien was pulibshed in Amsterdam by Jan ten Hoorn. It offered visitors to the Dutch Republic a meticulously organized overview of its provinces, cities, inns, and public transportation routes by barge and wagon. Delft, where Vermeer lived and worked his entire life, is described in detail—its churches, market square, civic buildings, and trekschuit timetables are all set down with a factual precision that echoes the clarity of Vermeer’s own painted interiors.

Amsterdam, by Jan ten Hoorn, 1689

Full title (translated): Travel Book through the United Netherlands Provinces, and Their Neighboring Regions and Kingdoms; Containing a Precise Description of the Cities, with Indications of the Boat and Wagon Routes, along with Suitable Inns Where Travelers May Lodge in Each City, and Other Useful Travel Information.

The book provides route-by-route descriptions linking the principal towns of the Republic, including distances, modes of transport, inns, ferries, canals, and roads. Cities are treated individually, with notes on their political status, civic institutions, churches, markets, fortifications, and noteworthy buildings. Attention is often given to what a visitor "ought to see," reflecting contemporary ideas of civic pride and urban identity rather than artistic taste in the modern sense.

Its Delft imprint is significant (pages 56–61). Delft was not only a manufacturing and artistic center but also an active printing town with a readership that included merchants, officials, and educated travelers. The appearance of such a guide there in 1689 points to sustained internal mobility even after the most prosperous decades of the Golden Age had passed. Travel within the Republic remained dense and regular, supported by an advanced network of canals, trekschuiten, and posted routes.

Unlike earlier chorographical works, which were often expansive and scholarly, the Reis-Boek is compact and utilitarian. It reflects a practical mentality shaped by commerce and administration: time, distance, and convenience matter as much as historical anecdote. At the same time, its tone assumes a reader familiar with civic order, Protestant institutions, and the political framework of the States General, revealing the shared cultural ground of its audience.

For historians, the book is valuable as evidence of how the United Provinces were experienced on the ground in the late seventeenth century. It helps reconstruct patterns of movement, the relative importance of towns, and the expectations placed on urban spaces by travelers. For those studying Delft and its wider connections, the Reis-Boek offers a modest but reliable window onto how the Republic presented itself to those moving through it in 1689.

Although the guide was compiled after Vermeer’s time, it captures the infrastructure and rhythm of a city still largely as he would have known it. When read alongside paintings like The Little Street or View of Delft, it sharpens our understanding of Delft not as a timeless backdrop but as a living city—quietly ordered, intimately navigated, and thoroughly embedded in the well-regulated world of the Dutch Republic. The Reis-Boek reminds us that behind the serenity of Vermeer’s scenes stood a civic structure that was no less meticulously composed.

In "Dutch Travel Journals from the Sixteenth to the Early Nineteenth Centuries,"* R. M. Dekker examines nearly five hundred surviving manuscript travel journals written by inhabitants of the northern Netherlands between about 1500 and 1814. These texts are treated as egodocuments: first-person accounts in which travelers recorded their own experiences rather than compiling impersonal guidebooks or official reports. The study does not claim that these journals represent Dutch travel as a whole; instead, it shows how travel was experienced, narrated, and remembered, largely by members of the social elite.

For the 17th century, the journals reveal a society in which travel was already widespread, though not yet "tourism" in the modern sense. Journeys were undertaken for education, religion, diplomacy, commerce, health, and scholarly exchange, with leisure often interwoven rather than dominant. The medieval pilgrimage still lingered at the century’s opening but quickly declined, replaced above all by the grand tourIn contrast a type of journey in the ascendent in the seventeenth century is the grand tour. It became common practice for young people from good families to complete their education with a journey abroad, often under the supervision of a tutor. In particular France and Italy were visited, where often some time was spent in study at a university and obtaining a prestigious doctorate. But it was at least as important to acquire the necessary culture and knowledge of the world. In her dissertation on the grand tour, Anna Frank-van Westrienen has analyzed this type of travel account thoroughly. (R. M. Dekker, "Dutch Travel Journals from the Sixteenth to the Early Nineteenth Centuries," trans. Gerard T. Moran, Lias: Sources and Documents Relating to the Early Modern History of Ideas 22 (1995): 277–300.), an educational journey for young men from wealthy families. France and Italy were the principal destinations, valued for universities, classical remains, art, and courtly culture. These tours were expensive, carefully planned, and usually supervised by tutors.

The journals show that travel writing followed recognizable conventions. Authors almost always recorded routes, transport, inns, expenses, notable buildings, artworks, curiosities, and social encounters. Many listed traveling companions and sometimes appended inventories of clothing, books, or baggage. Some journals included drawings, maps, or collected prints, especially when the traveler had artistic training. Professional painters were particularly inclined to illustrate their accounts, turning the journal into a hybrid of diary and sketchbook.

Socially, seventeenth-century travel journals were overwhelmingly written by regents, nobles, scholars, clergy, merchants, and artists. Ordinary people traveled extensively for work, but they left almost no written record. Women appear only rarely, and when they do, their journeys were usually undertaken with family members. Writing a travel journal itself was part of elite culture, tied to education, self-discipline, and memory.

Motives for writing varied. Some authors wrote for themselves, to preserve memories; many wrote for parents, spouses, relatives, or future descendants. Journals were often read aloud at home or circulated within a small social circle. Others were written with a broader audience in mind or later served as the basis for lectures or printed works. Dissatisfaction with existing guidebooks frequently prompted travelers to record what they saw "correctly" for those who might follow.

The article also shows that 17th-century Dutch travelers already moved within a shared culture of expectation. People traveled knowing what others before them had seen, read, and recorded. Travel accounts shaped later journeys, creating a feedback loop between reading and traveling. Although these journals cannot be taken as a complete picture of Dutch mobility, they clearly document a transition: from medieval religious travel toward educational journeys and, by the late seventeenth century, the early foundations of leisure-oriented travel that would fully emerge in the eighteenth century.

Among the many travel journals discussed by R. M. Dekker, a relatively small group stands out as especially important, either because of their early date, exceptional scope, richness of observation, or influence on later travel writing. What follows is a selective overview rather than a complete ranking.

One of the most significant early documents is the pilgrimage account of Arent Willemsz (active early 16th century), a barber from Delft who recorded his journey to Jerusalem. At more than 300 pages, it is unusually long for its period and marks the transition from medieval devotional travel toward more individualized narrative forms. It shows how travel could already function as personal testimony well before the rise of secular tourism.

For the late 16th and early 17th centuries, the journals of Aernout van Buchell (1565–1641) are fundamental. His extensive descriptions of journeys through Italy and other parts of Europe combine antiquarian interests, architectural observation, and personal reflection. They provide a model for learned travel writing and are indispensable for understanding scholarly mobility in the early Dutch Republic.

Within the tradition of the grand tour, the journals of the Van der Dussen brothers (mid-17th century) are especially important because both draft and revised versions survive. This allows historians to study not only what travelers observed but also how travel experiences were reshaped into more polished narratives, revealing contemporary ideas about memory, order, and self-presentation.

Among artist-authored journals, the Italian travel account of Vincent van der Vinne (1628–1702) is one of the most valuable. Richly illustrated, it documents how painters traveled to study art, meet colleagues, and absorb foreign styles. It also shows how visual artists differed from scholars or regents in what they chose to record, giving special attention to workshops, collections, and urban views.

For long-distance and non-European travel, the journal of Reynier Adriaensens (active late 17th century), a Dutch East India Company soldier, is one of the most revealing. Covering his voyage to Batavia and his experiences in Asia, it offers rare firsthand testimony about colonial life, disease, violence, and social tensions, written for readers at home who were considering similar journeys.

In terms of sheer scale and ambition, the travel journal of Rutger Meetelerkamp (1719–1779) is among the most extraordinary in the entire corpus, running to well over 1,400 pages. Though eighteenth century, it is crucial for showing how earlier 17th-century traditions of detailed observation developed into exhaustive narrative projects that blurred the line between manuscript journal and publishable book.

Finally, the journals of Balthasar Bekker (1634–1698), recording his travels in England and France, are important not only as travel accounts but as intellectual documents. They show how scholars used travel to build networks, exchange ideas, and observe foreign religious and academic cultures, making them central to the history of knowledge circulation.

Taken together, these documents matter because they do more than record movement. They define how travel was understood, justified, narrated, and remembered in the seventeenth-century Netherlands. They also explain why later generations traveled as they did: not blindly, but guided by what earlier travelers had already written.

Dekker’s study demonstrates that the Dutch Republic possessed a deeply rooted travel culture well before modern tourism, and that 17th-century travel journals are essential sources for understanding how travel was practiced, valued, and narrated within that society

*Dekker, R. M. Dutch Travel Journals from the Sixteenth to the Early Nineteenth Centuries. Translated by Gerard T. Moran. Lias: Sources and Documents Relating to the Early Modern History of Ideas 22 (1995): 277–300.

DELFT (Translation of pages 56–61 of Reis-Boek door de Vereenigde Nederlandtsche Provintien

Page 56

Delft is not the second, as some say, but the third city of Holland, based on its place in the Assembly of the Heeren Staaten (Lords States) of the country.

It was excellently and strongly founded by Godevaart met de Bult around the year 1075 (others say 1071). This Godevaart, relying on the wealth of Willem, Bishop of Utrecht, drove out Robrecht den Vries, guardian of Diderik, son of Floris the First, and took all of Holland; afterwards, with his army, he moved into Westfriesland to subdue it as well, and thus by force or treaty he conquered nearly all the cities. But, having ruled for barely four years, he was overthrown by the cunning of Robrecht, who harbored an implacable hatred against him—just as in Antwerp he was secretly active with his followers, and ended up being stabbed in his sleep.

In the year 1351, the principal church within Delft was established, and consecrated to St. Hippolytus; it is said that for thirty years its design had been seen hovering in the air. Among the many famous tombs, are found those of the widely known sea heroes Pieter Pietersen Hein and Maerten...

Page 57

Harpertzen Tromp, in stately tombs, laid to rest in memory of their courage and service to the country, which they sealed with their deaths.

Another is now the Nieuwe Kerk, formerly dedicated to St. Ursula. This church may be called the Royal Tomb, established in memory of Willem van Nassau, Prince of Orange, etc., who was treacherously shot with a pistol in the city of Delft on July 10, 1584, in his residence by an assassin named Balthazar Gerards. This prince was the first founder of the desired state of the Free United Netherlands, which he secured by the sword through the courage of the country's governors and the wise policies of his illustrious descendants. At this splendid tomb, adorned with bronze and marble statues, there stands an excellent inscription that cannot be found elsewhere.

The body of Prince Maurits was likewise laid in this princely tomb in the year 1625; that of Frederik Hendrik in 1647, and that of Willem II in 1650.

In the year 1449, the Minnebroeders Monastery was founded. Also, near the Oude Kerk, a monastery of St. Agatha was founded—now called the Prinsenhof, where Prince Willem kept his court, where this prince was wounded, and which later became the Staple Hall for English cloth.

Opposite the Nieuwe Kerk, there once stood a Town Hall with a beautiful tower, which in 1618 was destroyed by fire that nearly consumed the entire city. One barely managed to save it, but the tower with its fine clockwork was preserved through great effort. Later, on the same site, a splendid Stadhuis (Town Hall) was rebuilt, richly adorned with stonework…

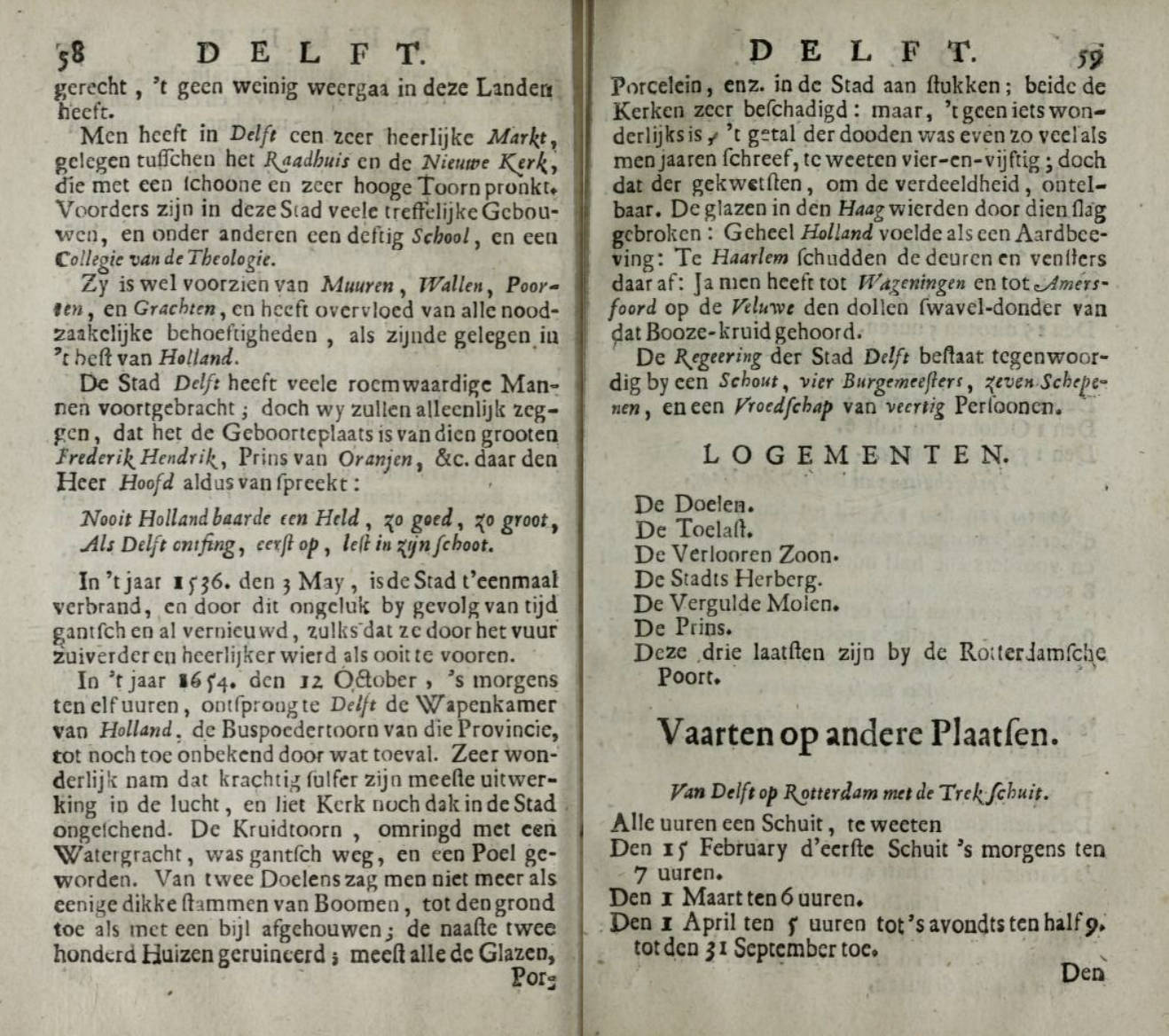

Page 58

…built, a structure with few equals in these lands.

In Delft there is a most splendid Market, situated between the Town Hall and the Nieuwe Kerk, in which a beautiful and very tall tower stands. Furthermore, the city contains many excellent buildings, among them a fine School, and a College of Theology.

It is well supplied with walls, ramparts, gates, and canals, and has an abundance of all necessary provisions, being located in the heart of Holland.

The city of Delft has produced many illustrious men, but it can rightly be said to be the birthplace of the great Frederik Hendrik, Prince of Orange, etc., about whom Heer Hooft speaks thus:

Never did Holland bear a hero so good, so great;

When Delft brought him forth, it rose and bore him in its bosom.

In the year 1536, on the 3rd of May, the city once again burned down, and because of this accident and the passing of time, it was entirely rebuilt and renewed, such that it became purer and more glorious from the fire than it had ever been before.

In the year 1654, on the 12th of October, at eleven in the morning, an explosion occurred in Delft in the Armory of Holland, the Powder Magazine Tower of the Province. To this day it is unknown what caused the accident. The force of the sulfur blast was incredibly strong, hurling itself into the sky and destroying the roof of the church as well as many houses in the city. The Gunpowder Tower, surrounded by a water moat, was entirely obliterated and became a pond. From two Doelen (archery ranges) one could no longer see a single thick tree trunk remaining; they had all been felled to the ground or broken off mid-height. The surrounding several hundred houses were ruined; most of the windows…

Page 59

Porcelain, etc., in the city was shattered into pieces; both churches were heavily damaged. But—though it sounds unbelievable—the number of the dead was, according to most accounts, exactly fifty-four; yet the number of wounded, due to the chaos, is uncountable.

The windows in The Hague were smashed by the shockwave. All of Holland felt as if there had been an earthquake. In Haarlem, doors and windows rattled from it. Indeed, it is said that as far as Wageningen and Amersfoort, on the Veluwe, people heard the wild, sulfurous thunder of the gunpowder explosion.

The government of the city of Delft currently consists of a Schout (sheriff), four Burgemeesters (mayors), seven Schepenen (aldermen), and a Vroedschap (council) of forty persons.

LODGINGS

- The Doelen

- The Toelaast

- The Lost Son

- The City Inn

- The Gilded Mill

- The Prince

These last three are near the Rotterdam Gate.

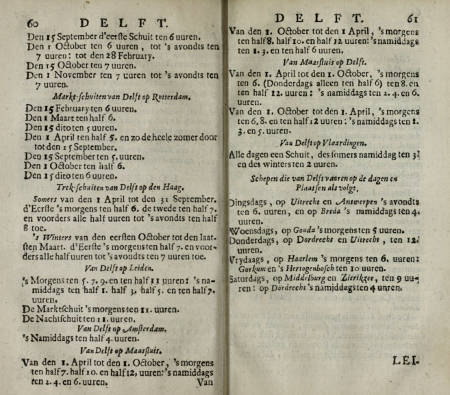

TRAVELS TO OTHER PLACES

From Delft to Rotterdam by tow barge (Trekvaart)

A boat every hour, namely: From February 15, the first barge leaves in the morning at 7 o’clock.

- From March 1, at 6 o’clock.

- From April 1, from 5 in the morning until half past 9 in the evening,

until September 31

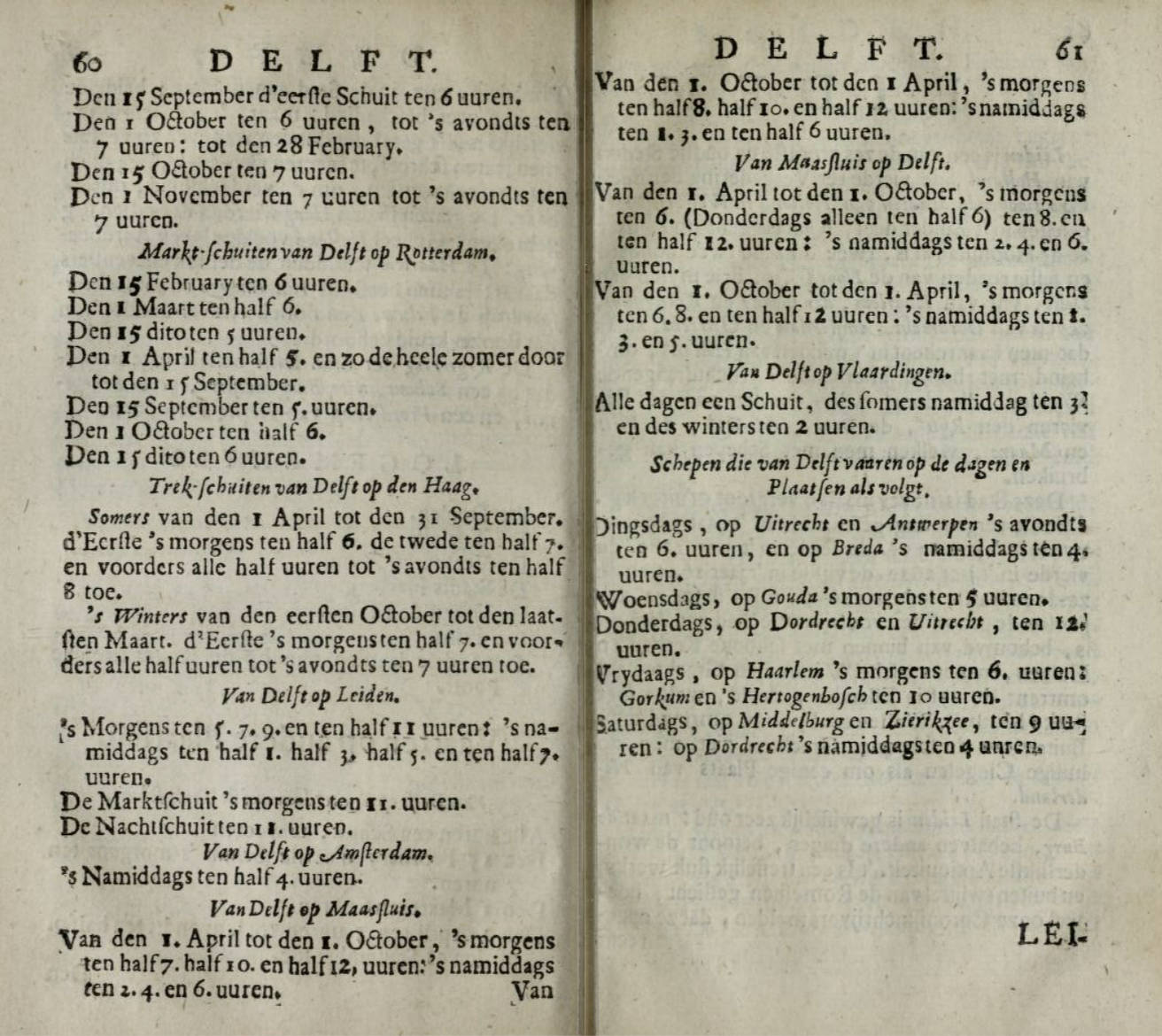

Page 60

- From 15 September, the first barge at 6 o'clock.

- From 1 October, at 6 o'clock, until 7 in the evening: until 28 February.

- From 15 October, at 7 o'clock.

- From 1 November, at 7 o'clock until 7 in the evening.

Market barges from Delft to Rotterdam

- 15 February at 6 o'clock.

- 1 March at 5:30.

- 15th of same month at 5 o'clock.

- 1 April at 4:30, and continuing all summer until 15 September.

- 15 September at 5 o'clock.

- 1 October at 5:30.

- 15th of same month at 6 o'clock

Tow barges from Delft to The Hague

Summer (from 1 April to 31 September):

- First barge departs at 5:30 AM, the second at 6:30 AM, and thereafter every half hour until 7:30 PM. Winter (from 1 October to 31 March):

- First barge departs at 6:30 AM, and thereafter every half hour until 7:00 PM.

From Delft to Leiden

- Morning at 5, 7, 9, and 10:30.

- Afternoon at 12:30, 1:30, 3:30, 5:30, and 6:30.

- The market barge at 11:00 in the morning.

- The night barge at 11:00 at night.

From Delft to Amsterdam

- In the afternoon at 3:30.

From Delft to Maassluis

- From 1 April to 1 October, in the morning at 6:30, 7:30, and 12:30.

Page 61

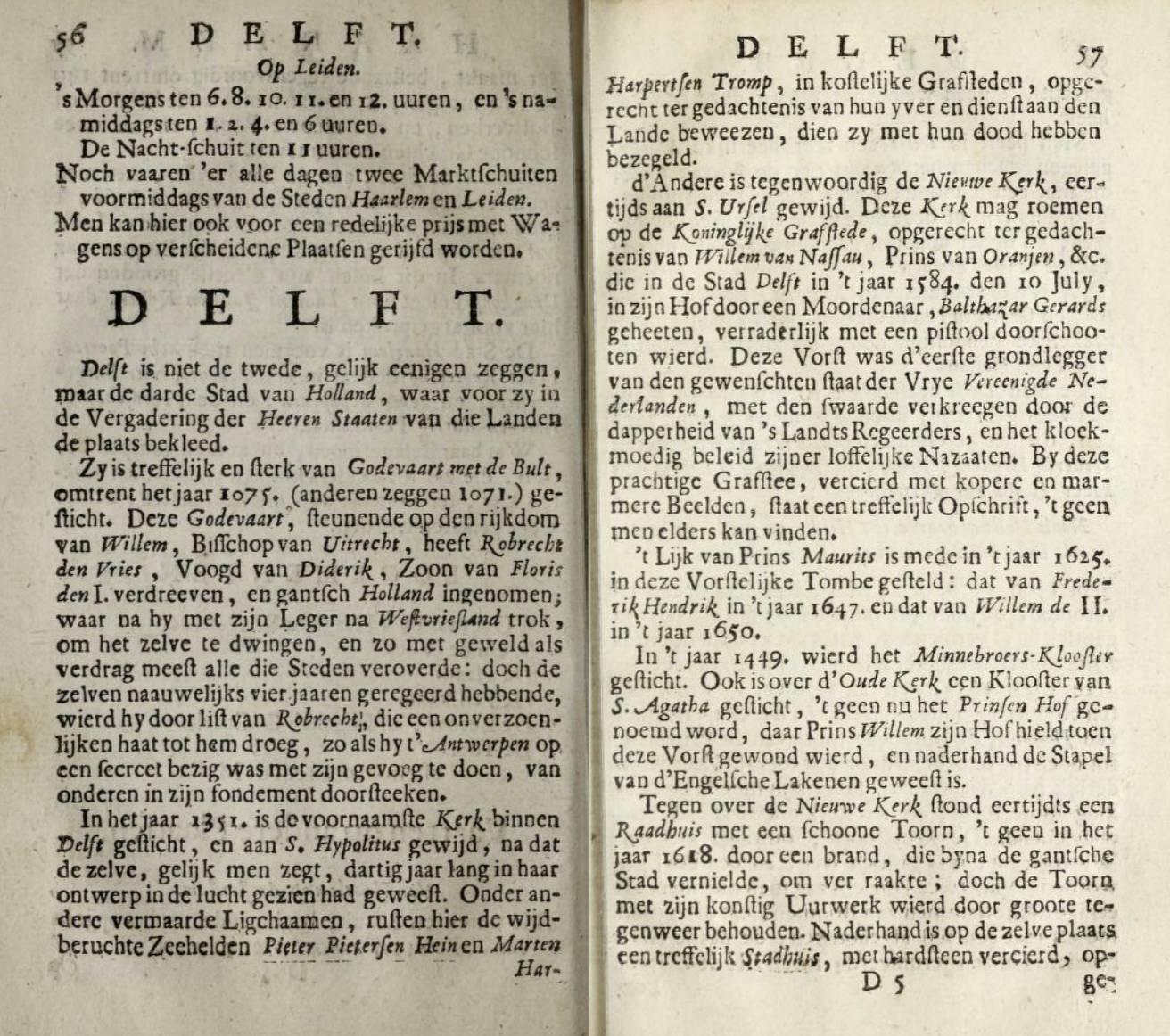

- In the afternoon at 2, 4, and 6 o’clock.

Here is the English translation of this final section regarding transport from and to Delft:

From Maassluis to Delft

- From 1 April to 1 October, in the morning at 6 (on Thursdays only at 5:30), 8, and 11:30; in the afternoon at 2, 4, and 6.

- From 1 October to 1 April, in the morning at 6, 8, and 11:30; in the afternoon at 1, 3, and 5.

From Delft to Vlaardingen

A barge every day:

- In summer at 3:30 in the afternoon.

- In winter at 2 o'clock.

Ships that depart from Delft on the following days and to the following places:

- Tuesdays, to Utrecht and Antwerp at 6 in the evening, and to Breda at 4 in the afternoon.

- Wednesdays, to Gouda at 5 in the morning.

- Thursdays, to Dordrecht and Utrecht at 12 noon.

- Fridays, to Haarlem at 6 in the morning; to Gorinchem and ’s-Hertogenbosch at 10 in the morning.

- Saturdays, to Middelburg and Zierikzee at 9 in the evening; to Dordrecht at 4 in the afternoon.

This list, in a sort of proto-timetable style, reflects the highly structured and well-developed canal and waterborne transport system of the Dutch Republic in the early modern period. If you'd like a clean transcription or formatted table for this data, I’d be happy to help.