The question of whether Vermeer ever produced a true self-portrait has occupied scholars for more than a century, yet the surviving evidence remains indirect, dispersed, and at times contradictory. The most explicit documentary reference occurs in the catalogue of the Dissius estate auction, held in Amsterdam on 16 May 1696, which listed twenty-one paintings by Vermeer. Item number three was described as ’t Portrait van Vermeer in een Kamer met verscheyde bywerk ongemeen fraai van hem geschildert (“a portrait of Vermeer in a room with various accessories, uncommonly beautifully painted by him”).The picture sold for forty-five guilders. This work has not survived, and its loss remains one of the most tantalizing gaps in Vermeer’s oeuvre .

From an early stage, some commentators proposed that this description referred to The Art of Painting (fig. 1), now in Vienna. While nothing in the catalogue description categorically excludes this possibility, modern scholarship overwhelmingly rejects the identification. The decisive objection is economic. In the same auction, The Milkmaid realized 175 guilders, Woman Holding a Balance 155 guilders, and View of Delft no less than 200 guilders. Even allowing for fluctuations in taste among Amsterdam collectors, it is implausible that an ambitious, carefully orchestrated composition such as The Art of Painting—with its exceptional mastery of three-point perspective, rarely matched by interior painters of the time—would have fetched a mere forty-five guilders. Perspective, moreover, was widely admired in Vermeer’s own lifetime. The only contemporary written assessment of his work, a diary entry by the young aristocrat Pieter Teding van Berckhout, praised not poetic ambiguity or suspended time but the extraordinary quality of Vermeer’s perspective. The market further confirms this valuation: only three years later, in 1699, Vermeer’s Allegory of Faith, comparable in scale and perspectival construction to The Art of Painting, fetched 400 guilders, the highest recorded price for a Vermeer in the seventeenth century. These considerations make it far more likely that lot three represented a distinct, now-lost work rather than the Vienna painting.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1668

Oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Johannes Vermeer

1656

Oil on canvas, 143 x 130 cm.

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

The Vienna picture itself resists identification as a self-portrait for additional reasons. The artist is shown from behind, his face deliberately withheld, shifting attention from individual identity to the dignity of the painter’s craft. Although some have compared the painter’s chestnut-colored hair—visible beneath the black beret—to that of the left-hand figure in The Procuress (fig. 2), as well as to the hair of the male protagonists in The Geographer and The Astronomer, such similarities are ultimately inconclusive.In 17th-c. Dutch painting, artists at work in their studios are often depicted wearing berets, as in Vermeer’s own representation of the painter in The Art of Painting; however, broad-brimmed hats are also a common feature in such imagery. Precedents were available to Vermeer in which an artist appears working in a background room seen through a doorway, sometimes accompanied by a dog lingering at the threshold, as in Michael Sweerts’s Artist’s Studio with a Seamstress (c. 1646–1649). Comparable hairstyles appear frequently in Dutch studio scenes of the period. Documentary evidence further undermines the self-portrait hypothesis: during legal proceedings aimed at preventing The Art of Painting from being sold to satisfy Vermeer’s debts, his widow Catharina Bolnes (c. 1631–1688) referred to it explicitly as “een schilderije waerinne wert uitgebeelt de Schilderconst”—a painting in which the art of painting is represented—rather than as a likeness of her late husband.

More persuasive as a potential self-representation is the grinning man at the far left of The Procuress, often identified as a depiction of the artist at about twenty-four years of age. His marginal placement, direct gaze toward the viewer, and the somewhat awkward rendering of his right hand are traits commonly associated with mirror-assisted self-portraits. He is cast as a musician or rake, wearing a black velvet beret tilted at a rakish angle and an old-fashioned slashed doubletIn The Art of Painting, the painter is shown wearing a luxurious black silk doublet cut with numerous narrow vertical slashes that reveal a white shirt beneath. Together with the beret, puffed breeches, and red stockings, this costume forms an idealized and fictive attire that would have been wholly impractical for studio labor. Rather than functioning as a literal self-portrait, the outfit operates allegorically, distancing the figure from everyday craft and presenting painting as a learned activity aligned with the liberal arts and elevated social status. Although this costume has sometimes been described as archaic or “Burgundian,” the slashed doublet in fact reflects a revival of a fashion current in the 1620s–1630s that briefly returned in the early 1660s. Such extremely short doublets, known in Holland as innocents, appear here in a refined form with finer, narrower slashes than earlier examples, marking the garment as contemporary at the time the painting was made. Vermeer had already explored this motif in The Procuress of 1656, where broader, already outdated slashes appear on the musician at left. While rare in mid-17th.c. portraiture, the fashion is documented by a surviving silk suit dated 1662, and in The Art of Painting Vermeer exploits the rhythmic slashes and shifting highlights as a demonstration of his command of complex textures and light on fabric. with a stiff white collar. This deliberately disreputable costume has been interpreted as a narrative device: a theatrical persona who introduces the viewer to the scene’s calculated excess and moral ambiguity, while simultaneously allowing the artist a fleeting, ironic appearance within his own painting.

Technical examination has revealed further, more elusive traces of Vermeer’s presence in his work. In A Maid Asleep, imaging studies show that the composition originally included a man in the back room and a dog positioned in the doorway, both of which were later painted out. The male figure, visible through the doorway of the rear space, appears to have been an artist working at an easel. His apparent left-handedness has prompted the suggestion that this figure may not represent a straightforward depiction, but rather a reflected image—possibly of Vermeer himself—seen indirectly through a mirror.

This interpretation is set out in detail by Dorothy Mahon, Silvia A. Centeno, and Federico Carò in their technical study of A Maid Asleep and Study of a Young Woman in Closer to Vermeer.Dorothy Mahon, Silvia A. Centeno, and Federico Carò, "A Maid Asleep and Study of a Young Woman," in Closer to Vermeer: New Research on the Painter and His Art, ed. Anna Krekeler, Francesca Gabrieli, Annelies van Loon, and Ige Verslype (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum / Veurne: Hannibal Books, 2025). Reexamining the painting using advanced non-invasive imaging methods, including macroscopic X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF)MA-XRF (macroscopic X-ray fluorescence imaging) is a non-invasive analytical technique that maps the distribution of chemical elements across a painting’s surface, allowing conservators to identify pigments and visualize underlying paint layers without sampling. In art conservation, it is especially valuable for reconstructing earlier compositional stages and distinguishing original paint from later alterations or overpainting. , the authors reconstruct earlier compositional stages with a degree of clarity not previously possible. Their argument does not rest on iconographic conjecture, but on material evidence revealed through chemical mapping of the paint layers.

Earlier X-radiographs had already demonstrated that Vermeer initially painted a male figure visible through the doorway, later removing him along with other elements such as a dog near the threshold and a plate on the table. Mahon, Centeno, and Carò show that MA-XRF maps—particularly those tracking copper- and mercury-based pigments—allow a more complete reconstruction of this hidden figure. In one stage of the composition, the man is oriented toward the viewer, his body angled slightly forward, with one arm raised in a gesture consistent with someone actively engaged in painting at an easel, possibly while seated on a low stool. The authors consider and reject alternative interpretations of the raised arm, such as a gesture of farewell or a toast, noting that the spatial and narrative context offers no justification for such readings.

A further, highly technical aspect of their analysis concerns architectural elements in the background room. What appears in the finished painting as part of a window frame corresponds, in the lead distribution maps, to vertical forms that closely resemble the upright supports of an easel. The surrounding lead-white paint indicates that the wall was once worked around these vertical elements, suggesting that Vermeer did not simply remove the painter, but instead reconfigured parts of the original pictorial apparatus into the final architectural structure of the room.

Within this framework, Mahon, Centeno, and Carò address the unusual detail that the concealed painter appears to be left-handed, since artists are most typically depicted working with their right hand. They propose that this anomaly may indicate a reflected image rather than a direct representation, possibly of Vermeer himself. In this scenario, the artist would have been working in the room with the young woman, outside the picture plane, while his reflection was captured in a mirror placed in the room across the hallway. Comparable strategies are known in seventeenth-century Dutch genre painting, including examples by Nicolaes Maes, in which artists appear indirectly through mirrored or displaced reflections. A specific precedent is Maes’s The Naughty Drummer (c. 1655) (fig. 3), where the artist includes a reflected image of himself working in a studio mirror placed above his subjects. Although it is not certain that the two artists knew each other, some scholars have suggested that this is likely, and Vermeer’s interest in optics and reflections is well known. At the same time, the authors also consider the possibility that, at an earlier stage, the man was angled facing away from the viewer, with his right arm raised, a pose somewhat comparable to that of the artist depicted in The Art of Painting. Either way, the presence of an artist working at an easel supports the interpretation that the woman dozing at the table was originally conceived as an artist’s model.

Nicolaes Maes

c. 1655

Oil on canvas, 62 x 66.4 cm.

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

On this basis, the authors cautiously advance the possibility that the hidden painter could represent Vermeer himself. They do not assert this identification as certain, but argue that the reflective logic of the image, combined with the technical evidence and the left-handed appearance, makes such an interpretation plausible. In their concluding remarks, they state with confidence that the concealed figure was intended as an artist working at an easel and suggest that Vermeer may originally have conceived A Maid Asleep as a scene involving an artist and a model, the woman’s dozing posture perhaps indicating fatigue after posing. Only later, through systematic revision, did Vermeer remove this self-referential dimension and arrive at the more ambiguous and psychologically understated composition seen today.

Pieter Janssens Elinga produced several meticulously constructed interior scenes, often organized around tiled floors and strong perspectival recession, in which a painter at an easel appears in a background room or through a doorway. One of the clearest examples is Interior with Painter, Woman Reading a Letter (c. 1660s) (fig. 4), where the foreground is occupied by a quiet domestic scene while, in the distance, a painter preumably works standing at his easel in a secondary space. The figure is not the narrative focus but functions as a structural and conceptual anchor, reinforcing the perspectival depth of the composition and quietly asserting the presence of artistic labor within the domestic interior. What makes Elinga especially relevant to your discussion is that this motif—an artist working in the background, partially removed from the viewer and framed by architectural thresholds—anticipates the kind of spatial logic proposed for A Maid Asleep. In Elinga’s case, the painter is not a self-portrait in any strict sense, but the composition demonstrates that the idea of situating the artist indirectly within a domestic interior, visible through a doorway and subordinate to the main scene, was already available within Vermeer’s artistic milieu. This strengthens the plausibility that Vermeer could have experimented with a comparable strategy—whether reflective, displaced, or deliberately understated—without departing from contemporary pictorial conventions.

Pieter Janssens Elinga

c. 1665–1670

Oil on canvas, 82 x 99 cm.

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

A similar strategy operates in The Music Lesson, where the mirror above the virginal reflects the tiled floor, the table, and the legs of the artist’s easel without disclosing the painter’s face (fig. 5). This calculated omission draws attention to the constructed nature of the scene and affirms the artist’s role as its unseen witness. In Girl with a Red Hat, painted on an oak panel that already bore an unfinished portrait of a man in a wide-brimmed hat, some modern specialists have questioned the long-standing attribution of the underlying image to Carel Fabritius. Its forceful handling and its resemblance to the male figure in The Procuress have led to the suggestion that it could be an authentic early work by Vermeer himself, perhaps dating to around 1656.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1662–1665

Oil on canvas, 73.3 x 64.5 cm.

The Royal Collection, The Windsor Castle

It is important to distinguish this case from other instances in which concealed male figures have been detected beneath Vermeer’s paintings. In Girl with the Red Hat, for example, advanced chemical imaging has revealed the presence of an earlier male figure beneath the surface, yet the authors of the technical study deliberately refrain from identifying this figure as an artist, a portrait, or a self-referential image. No easel, studio apparatus, or painterly gesture is implied, and no reflective logic is proposed to account for the figure’s orientation or appearance. The underlying man is treated strictly as a discarded compositional idea, possibly an unrelated figure study executed on the panel before it was reused. This restraint stands in marked contrast to A Maid Asleep, where multiple strands of technical evidence converge to support the interpretation of a painter at work—and where the possibility of a reflected image opens, for the first time, a technically grounded avenue for considering Vermeer’s indirect self-representation.

What emerges from this accumulation of evidence is a consistent pattern. Vermeer appears to have avoided direct self-display, preferring instead to register his presence obliquely—through narrative roles, reflected spaces, concealed figures, and theatrical personae. To approach his self-representation is therefore to encounter a deliberate reserve. The effects of his presence are everywhere felt, yet the artist himself remains carefully shielded from direct view.

Michiel van Musscher

Bass Museum

Miami Beach, Florida

The desire to identify a lost self-portrait has also led to repeated misattributions. In the nineteenth century, Théophile Thoré-Bürger identified a supposed self-portrait by Vermeer with a painting now securely attributed to Michiel van Musscher, believing it to be the same work sold for 480 guilders at a Hague auction in 1780. Van Musscher’s Portrait of a Young Artist in his Studio (fig. 6) is not without superficial affinities to Vermeer’s art: the hanging curtain, the foreground chair, and the window echo elements familiar from Vermeer’s interiors. Yet such motifs were widespread in genre painting of the period. Costume specialists at the Victoria and Albert Museum date the robe worn by the sitter to about 1660–1665, when Vermeer would have been around thirty, whereas the youthful face appears closer to that of a man in his early twenties. The painting lacks convincing stylistic evidence for an attribution to Vermeer, and its compromised condition further complicates judgment. The half-shaded face, heavy brow, and elongated nose do recall the figure in The Procuress, but such resemblances remain subjective. An engraving by Joannes Meyssens after the Van Musscher painting (fig. 7), bearing the inscription “Ver. Meer pinxit,” once lent the work spurious authority, yet the inscription appears to be a later addition, and the initials “VM” are no longer visible on the canvas, if they ever existed. Although the Bass Museum of Art at one time attributed the picture to Vermeer, it is now firmly credited to Van Musscher, a prolific portraitist whose surviving works include numerous depictions of artists in their studios, one of them clearly inspired by The Art of Painting.

Engraving

Joannes Meyssens

17th century

Dimensions unknown

Whereabouts unknown

Johannes Vermeer

1656

Oil on canvas, 143 x 130 cm.

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

Michiel van Musscher

Bass Museum

Miami Beach, Florida

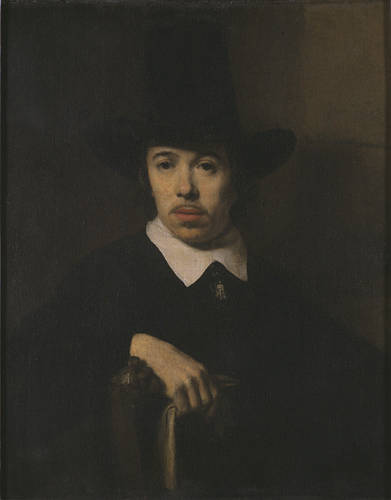

currently attributed to Nicolaes Maes

Oil on canvas, 73 x 59.5 cm.

Musée Royal de Beaux-Arts, Brussels

Other candidates proposed as the lost Dissius portrait fare no better. A Portrait of an Unknown Man in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels (fig. 8), once advanced as the missing self-portrait, can be dismissed outright, as it lacks the “various accessories” specified in the auction catalogue.

The painting in question depicts a young man seated in a lion-headed chair, a furnishing that recurs in several of Vermeer’s secure works and has therefore long attracted attention. The sitter is shown full face, dressed in black, with a plain white collar fastened by a small gold ornament and a high-crowned black hat. He holds a pair of gloves, while his right hand rests casually on the back of the chair, a pose consistent with contemporary portrait conventions and, more specifically, with representations of artists portraying themselves.

The attribution history of this work is unusually complex. In 1836 it was listed by John Smith as a painting by Rembrandt, supposedly signed and dated 1644—claims that were later disproved, leading to the removal of both signature and date. When the painting entered the Brussels Museum in 1900, it did so under an attribution to Nicolaes Maes. A decisive shift occurred in 1905, when A. J. Wauters, writing in The Burlington Magazine, proposed that the work should instead be assigned to Vermeer. Wauters based his argument on what he described as the painting’s peculiar technique and the distinctive handling of highlights, especially on the lion-headed chair, which he believed revealed Vermeer’s hand. This proposal, however, did not endure. The influential connoisseur Abraham Bredius later rejected the Vermeer attribution and reassigned the painting to Jan Victors (or Fictor; 1619–1676), a view that gained broader acceptance.

Several technical and stylistic objections ultimately prevented the painting from entering the Vermeer canon. Critics pointed in particular to the execution of the sitter’s hand, which lacks the subtle structure and refinement found in securely attributed works such as The Lacemaker. Moreover, leading authorities on Vermeer—including Cornelis Hofstede de Groot and W. R. Valentiner—consistently dismissed the attribution. While certain observers acknowledged superficial similarities in paint handling to works then accepted as Vermeer’s, such as the Portrait of a Woman in Budapest, the prevailing view was that these resemblances reflected shared conventions among contemporaries rather than authorship by Vermeer himself.

Despite these objections, the painting continued for a time to play a role in discussions of a possible Vermeer self-portrait. Around the turn of the twentieth century, it was occasionally linked to the lost “Portrait of Vermeer” recorded in the Dissius auction of 1696. That auction entry, however, is more often associated with The Art of Painting or regarded as referring to a completely lost work. The seated pose, the confident frontal presentation, and the presence of studio-like props nonetheless sustained the notion that the Brussels painting might represent an artist portraying himself. By the mid-twentieth century, as the Vermeer attribution was largely abandoned, this idea receded as well. What remains is a telling episode in the broader debate: a painting that once seemed to promise a direct likeness of Vermeer, yet ultimately reinforces how fragments of his pictorial language—chairs, gestures, lighting effects—circulate across his circle, while a definitive painted image of the artist himself continues to evade identification.