Girl Interrupted in her Music

c. 1658–1661Oil on canvas

39.3 x 44.4 cm. (15 1/2 x 17 1/2 in.)

Frick Collection, New York

Unlike her peers in the other two paintings, the young woman in Girl Interrupted at her Music from the Frick Collection in New York is dressed informally. She wears a jacket, a comfortable housecoat with straight sleeves, in which Vermeer would often depict his women from the early 1660s onwards.

The woman's domestic attire underscores the intimate nature of the man and woman’s interaction. Whereas the protagonists in the other two representations welcome their company in their finest trappings, she receives her guest comfortably dressed in her private domain. Vermeer may have intended this domestic setting to indicate that the man is no stranger to her.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1659–1662

Oil on canvas, 78 x 67 cm.

Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Brunswick

Like the leading lady in Girl with a Wine Glass (fig. 1), she makes contact with the viewer through her gaze; however, her facial expression is less easy to fathom. The cloth cap covering her head more or less shields her face from the male visitor who, like the two gentlemen in the other paintings, still has his cloak on. Does she wish to keep the gallant at bay? On the table is a cittern and an open music book, which the woman may have put down upon his arrival. The man grasps the sheet of paper she holds in her hands, and it is unclear whether he is giving or taking it. The paper connects the man and woman, an inventive motif derived from Frans van Mieris’s Teasing the Pet (fig. 2), in which a roguish gentleman forces himself on a young woman by tugging on her lapdog’s ear. As in the picture by Van Mieris, the caller makes advances towards the young woman. Nothing seems to be written on the paper; however, this is most likely due to the condition of the paint surface, which is abraded locally. Possibly, a music score or the lyrics of a song could have been read.

On the wall behind the couple is a painting of Cupid, which Vermeer depicted no fewer than four times with minor variations in his interiors. It may be a lost work by Caesar van Everdingen. The inclusion of the standing, nude, god of love with bow and arrow, who looks at the viewer just like the woman, underscores the amorous nature of the encounter between the lady and her company. Because this painting-within-a-painting was overpainted in the past and subsequently restored, the paint layer is abraded. Originally it would have been easier to discern how Cupid seems to comment on the man’s seductive wiles from behind the latter’s back. Both the woman and Cupid peer at the viewer, who is thus directly drawn into Vermeer’s painted scene. The Delft blue wine jug and the filled wine glass on the table suggest that alcohol is involved here as well.

Frans van Mieris

1660

Oil on panel, 27.7 x 19.9 cm.

Mauritsuis, The Hague

Technical investigation has revealed numerous additional facts about Girl Interrupted at her Music, which is much smaller than the other two works. For instance, various research techniques determined that the birdcage is most likely a later overpainting that does not belong in the picture. Moreover, a second window was originally included in the corner of the room, with a translucent blue curtain in front of the upper windows, exactly as in The Glass of Wine. Advanced research on the canvas weave in which the threads of the fabric were counted and compared with those in other paintings by Vermeer, yielded another remarkable find. Girl Interrupted at her Music must have been painted a few years later than was previously assumed because it appears to have come from the same piece of prepared canvas as Young Woman with a Water Pitcher, whose dating is estimated as being no earlier than 1662. Evidently, Vermeer did not paint these three representations in direct succession, but revisited the other two compositions, as it were, in Girl Interrupted at her Music. In doing so, he zoomed in more on the figures and omitted some iconic elements, such as the tiled floor and the stained-glass window.

Most Dutch genre painters favored scenes which included some specific action. In Jan Steen's Music Master (fig. 3) of about 1659 or Frans van Mieris's The Duet (fig. 4) of 1658, for example, figures are engrossed in each other and in the making of music. In each instance a young attendant enters the room, adding to the level of activity. Vermeer, in a number of paintings from the end of the 1650s, sought to achieve similar effects in his multifigured genre paintings. His results, however, were mixed at best. In Officer and Laughing Girl, The Glass of Wine, and The Girl with the Wine Glass, his attempts at rendering an action, whether it be laughing, drinking, or smiling, resulted in rather forced and artificial poses.

In the Girl Interrupted at Her Music Vermeer arrived at a solution for this problem: the momentary interruption. This device allowed him to suggest movement without the need for specific gestures and facial expressions that conflicted with the essential stillness of his compositions. In this painting the gentleman and the girl make a compact group as his form gently enfolds hers. She, however, rather than concentrating on the music they hold, looks out at the viewer. Her expression is alert and expectant, but not forced. Light falls gently across her face and on her white headpiece, accenting her gaze.

Jan Steen

probably 1659

Oil on oak, 42.3 x 33 cm.

National Gallery, London

Frans van Mieris

1658

Oil on panel, 31.5 x 24.6 cm.

Staatliches Museum, Schwerin

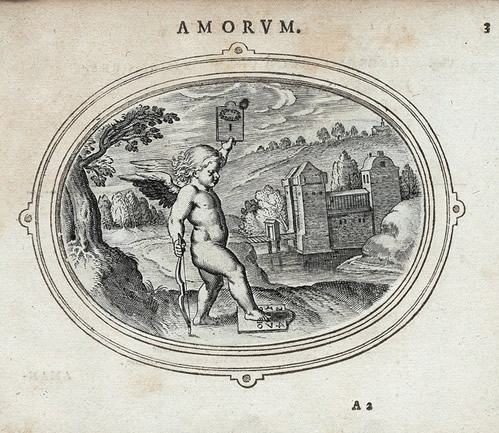

Vermeer may have used this pose to emphasize the meaning of his painting. Music is often associated with love, an association that is reinforced in this instance by the painting on the back wall (fig. 5). This painting, perhaps by Caesar van Everdingen, also appears in A Lady Standing at a Virginal (fig. 6), and was initially included in Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window. Its depiction of a cupid holding a card marked with a figure "I" is based on an emblem from Otto van Veen's Amorum Emblemata, (fig. 7) 1608. The emblem's motto, "Perfectus Amor non est nisi ad unum," states that perfect love is but for one lover. The woman's gaze out of the picture may thus have been intended to reinforce a didactic message. Interestingly, in A Lady Standing at a Virginal, the woman also looks out of the painting toward the viewer.

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1674

Oil on canvas, 51.7 x 45.2 cm.

National Gallery, London

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1658–1661

Oil on canvas, 39.3 x 44.4 cm.

Frick Collection, New York

ad Unum

Otto van Veen

Engraving from Amorum Emblemata

Antwerp, 1608

Unfortunately, this painting is in very bad condition. Only the still life area preserves something of its original surface qualities. The birdhouse on the side wall is an addition painted later by someone else and was not part of Vermeer's design.

Albert Blankert's conclusion that the Frick canvas might be a copy fails to explain its best preserved passages and even the evidence in the most damaged areas. The sunlight flooding through the window and over the chair in the foreground is superbly rendered and consistent with that found in other early interiors by Vermeer. On the table, the still life (fig. 8) of a blue and white pitcher with a silver cap, a cittern, a songbook (with detailed but indecipherable words and lute music), and a glass of red wine is composed in the precisely balanced manner one expects after studying The Glass of Wine). With the Braunschweig canvas, this picture and the one in Berlin demonstrate Vermeer's ability to produce variations not only on the themes of other artists but also on his own. In formal terms the process was demanding, a matter of constant refinement. With regard to meaning, by contrast, it all depended on a single notion, that of a young woman's disposition and character. Much less thought was devoted to the artist's male figures, who with the exception of Christ and two scholars hardly vary in type. In the company of women, Vermeer's men are mere attendants. They seek possession and lose themselves.

Johannes Vermeer