Vermeer's Neighborhood

(part two)

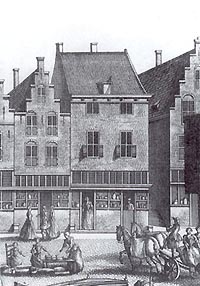

Mechelen

In 1641, on April 23, Vermeer's father, Reynier Jansz. Vos, bought the large and heavily mortgaged Mechelen inn (right a.) on Market Square at the corner with the Oude Manhuissteeg. He paid 200 guilders in cash and assumed two mortgages for the total value of 2,500 guilders. Mechelen had six fireplaces which tells us something of its size, the largest construction of the Markt . Like all the neighboring houses, the front side faced the Market Square and the backside plunged straight down into the Voldersgracht canal. The narrow Old Man's Alley ran alongside to a bridge over the canal behind (right b.). Mechelen was demolished in 1885 to make way for fire-prevention equipment.

The Mechelen Inn was the bustling heart of the town. Its location, with the town hall on one side and the Nieuwe Kerk on the other side. It was an ideal meeting place for discussions and exchanging news and archives show that many Delft artists also used to meet here for shop-talk.

The illustration below is a composite of a photograph taken of the the Market where Mechelen one stood and the historic engraving which shows Mechelen where it once stood..

On the occasion of Vermeer's wedding in 1653, the address registered was the house Mechelen where his father carried on various trades, the register also notes that his future wife, Catharina Bolnes, "lived there too." John Michael Montias maintains that it is highly unlikely that Catharina Bolnes, who, on her mothers side was from a devout Catholic family, would have actually lived with Vermeer in Mechelen before her marriage. Montias believes the clerk must have made an error. However, it has been recently advanced the idea that Catharina had gone to live with Vermeer thus forcing Catharina's mother, Maria Thins, to accept de facto of their sentimental relationship.

Mechelen

Sint-Lucasgilde

Het Straatje

Papenhoek

Stadhuis

mp3 audio files courtesy marco schuffelen

Judging from contemporary engravings Mechelen must have been a rather large house which certainly afforded ample space for the public-house business downstairs, for the trade in works of art and for the workshop for the "caffa" finishing. Vermeer's father was registered at the St. Luke's Guild as an art dealer and was also known to have worked in "caffa," a fabric similar to satin which was largely used for upholstery, clothes and curtains.

Inn-keeping and art dealing often went hand in hand. In these circumstances, it is obvious that the young Vermeer was exposed to the many paintings that adorned the walls of the inn as well as a chance to encounter artists and artisans who no doubt frequented the locale. Local Delft artists Evert van Aelst, Egbert van der Poel, and Leonaert Bramer must have been familiar faces. Mechelen was also spacious enough to contain Vermeer's wife when she moved in.

Mechelen no longer exists even though there is an erroneous commemorative plaque on the side on the building which was adjacent to it. Today, the alley is wider. The only image of the facade of Mechelen dates from an engraving of the early 18th c. by Leonard Schrenk (above right a.). Sometime between 1653 and 1660 Vermeer and his wife moved out of Mechelen to his mother-in-law's larger patrician residence on the other side of the Market Square. But Mechelen was still occupied by Vermeer's widowed mother until 1670, when she died and he inherited the property. Vermeer may have helped his aged mother run the inn, a taxing chore for even the healthiest of women, before he gave it up. Payments for Mechelen were still being made when Reynier's widow tried to sell it at auction in1669. In 1672 Vermeer lets Mechelen while he was living with his mother-in-law.

Both P.T.A. Swillens (Dutch historian and author of Vermeer: 1632-1675, 1950) and Philip Steadman believe that Vermeer painted directly from a rear window of Mechelen his Little Street.

"In 1955 a memorial tablet was placed on the wall of the adjoining house at number 52 the Markt, to mark the spot where Mechelen House once stood. The Delft sculptor Joh. Bijsterveld made the memorial tablet, which bears the following inscription: 'Here stood Mechelen House where the artist Jan Vermeer was born in 1632". This contains two mistakes. Vermeer was not born in Mechelen, as his parents moved there when he was already nine years old. The name Jan is not entirely correct either. Vermeer never used the name himself, He always signed deeds with Joannes, Joannis or Johannis. Criticism was heard on all sides in 1955, but the foundation 'Delft binnen de veste' (Delft within the ramparts) which devised the inscription, decided that the Christian name Jan had become more familiar."1

(a.) Mechelen

(b.) View of Old Men's Alley with Mechelen on the left, the building at the end of the alley is the Guildhouse of St. Luke.

Guild of Saint Luke

(from Johannes Vermeer, P.T.A.Swillens, Utrecht, 1950, p. 35)

the street sign bathed in Delft light at the beginning of Voldersgracht

On St. Luke's Day, October 18th, 1662, the artists of Delft chose Vermeer to be the vice-dean of their guild, which is another proof that at that time he must have been a respected and highly thought-of artist and citizen. When Johannes Vermeer took his place on the board of the Guild of St. Luke, he stepped into a quite new guildhouse, built and furnished by the artists of Delft exclusively for themselves. It had been put up a year before - 1661 - on the Voldersgracht, in the immediate neighborhood of Vermeer's birth-place on the Marktveld. Undoubtedly he watched it being built and completed from his own home. The building stood on the site of "the St. Christopher's or Old Men's House Chapel which had latterly served as a cloth-testing hall", according to the Delft chronicler Dirck van Bleyswijck . This author gives us a rather extensive description of the interior and exterior of the building. It had, according to him, "an imposing facade four ,window-sills broad, under each of which a garland is festooned carved in white stone with the different tools of the four chief trades belonging to this guild, viz. Artists, Glassmakers, China-makers, and Booksellers. Above the afore-mentioned cross-windows are the city's arms, those of the St. Luke's Guild and of Mr. Dean Dirck Meerman, Knight, Councilor and former Burgomaster as well as Chief Dike-Reeve of Delfland. In the top of the pediment appears the statue of Apelles, the most famous painter amongst the Ancients". Our illustrations (right b., c.) nearly correspond with this description of the exterior. The building was clearly erected in the classical Renaissance style. In 1879 it was pulled down to widen the alley. We still have the four festoons, they are set into the wall of the Rijksmuseum at Amsterdam.

(from John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History, Princeton, 1989)

The guild must have been the center of Vermeer's public life. There was little else in Delft of any conceivable interest for him. No publicly performed music, except for the playing of the organ in churches; no theater: the only Delft-born playwright, Gerrit van Santen, published his playlets in other towns but never saw them performed in Delft. The Chamber of Rhetoricians, which had once staged poetical contests and other shows, had long been inactive. Aside from a little poetry, religious for the most part, the literary scene was bleak. There was not enough intellectual ferment beyond art in Delft to keep a young artist from plying his craft.

Moreover, Vermeer had almost certainly converted to the Roman Catholic faith, which as we have seen, was repressed and intermittently persecuted. Provincial as Delft already was, belonging to the Catholic Church further narrowed a man's horizon because he was barred from all municipal functions. Election to the board of headmen of the guild was about the only civil honor to which the young artist could aspire, and that, no matter how talented he might be, he could not look forward to for several years. Election to the board of headmen did not normally come before a man was in his thirties or early forties.

(c.) the only surviving photograph of

Saint Luke's Guild made just before

it was demolished in 1879

St Luke's Guildhall

Abraham Rademaker

drawing c.1700

The Little Street

(from Anthony Bailey, Vermeer: A View of Delft, New York, 2001, pp. 100-101)

the newly reconstructed Vermeer Center which

was modeled on the original Guild of St. Luke

Het Straatje (The Little Street) is in fact a little painting of a small section of street. There is nothing to indicate how wide the street is, alhough we get the impression that the painter's view (which is our own) is from a house opposite, from an upstairs room, at no great distance. Topographical experts and local historians in Delft have spent much time trying to pin down where this was. The Oude Langendijk, the Nieuwe Langendijk, the Trompetstraat, the Spieringstraat, Achterom, the Vlamingstraat, and the Voldersgracht are among the numerous streets put forward for the honor. The Voldersgracht has been a consistent candidate, for the back of Mechelen overlooked the little canal of the Voldersgracht and its narrow carriageway, on to which faced the Old Men's Home and - a few doors further east—the Flying Fox inn. In a few years the Old Men's Home was going to be partly rebuilt, with its chapel converted in 1661 into the hall of the St Luke's Guild; drawings of the hall show a small house and archway similar to the part of the left-hand house and archway depicted in The Little Street. But the house on the right has its gable-end facing the street, while the building which housed the chapel of the Old Men's Home stood side-on to the street. The two arched outside doorways in the painting, one with a closed door, the other with door open revealing a brick-paved passage in which a servant-woman is leaning over a barrel used as a washtub or cistern, and waste water runs towards us along a gully form the heart of the picture. What is behind the dark closed door? Its shut state, the openness and light of its companion, bring to mind those weather-predicting devices styled as miniature cottages out of which figures swing to declare that it is going to be fine or rainy.

In 1950 the Dutch art historian P.T.A.Swillens was the first to propose that Vermeer's The Little Street (c.1657-1658) represents a view from the rear of Mechelen, the inn bought by Vermeer's father on the Market Square in Delft. Although it is certain that Vermeer moved in with his mother-in-law Maria Thins on the Oude Langendijk at some date between 1653 and 1660, Mechelen was still occupied by Vermeer's mother until 1670, when she died and he inherited the property and it is logical that the artist had access to it.

Unfortunately, the building which is represented in Vermeer's painting was demolished to make way for the St Luke's Guildhall in 1661. A drawing (c.1700) by Abraham Rademaker (right b.) has survived, and provides a fairly accurate idea of how the Guildhall must have appeared, Swillens projection (right e.) shows the scheme of the Guildhall as it appeared in Rademaker's drawing superimposed on Vermeer's composition. Philip Steadman has recently noted inaccuracies in Swillens projection and has furnished a more accurate projection by taking into account not only Rademaker's drawing but the only existing photograph of the Guild (right c.), itself torn down in 1879.

"One reason why Vermeer might have chosen this particular subject is that the Guild of St. Luke was his own guild, to which he had belonged since 1653. The new building displaced part of an older charitable institution, the Old Men's House. Vermeer must have known what was planned, and might have wanted to make a record of the older building before its transformation. The gateway to the left gave access to premises beyond, which continued to be occupied by the charity. The gate carries a board with the inscription 'Oude Manhuis.'"2

In 1982 a group of houses on Nieuwe Langendijk 22-26 were examined by a team from the Delft Polytechnic University together with a number of amateur archaeologists. The group of buildings seemed to date form the 16th-century or even earlier. Wim Weve, active in 1982 as an assistant in the Architecture Department of the Delft Polytechnic, noted that the rather large house was similar to those depicted by Vermeer. The buildings were demolished shortly after this research.

Vermeer specialist and independent art historian Kees Kaldenbach has done further research on the The Little Street based on the data provided by Weve and Van Haaften. In his cover article in Bulletin KNOB, Kaldenbach presents combines and weighs all relevant data. He lists a total of 14 arguments to support the buildings' identifications.

For further information regarding the presumed location of Vermeer's Little House, please see:

(e.) the old Delft Guildhouse projected

onto Vermeer's Little Street

(d.) The Saint Luke's Guild

on Voldersgracht, Delft

engraving by L. Schenk

after A. Rademaker, about 1732

Maria Thin's House

It is certain that Vermeer and his family moved to live with Maria Thins (Vermeer's mother-in-law who was a devout Catholic) on the Oude Langendijk at some date between 1653 and 1600 in the so-called "Papenhoek", or Papists' Corner. The Papist Corner was not a ghetto because many of the families who chose to live there, by their own free will, were prosperous. In Delft about a quarter of the population was Catholic. Although Catholics were not actively repressed, they were not altogether free to act as they would. It is not known for what reason the Vermeer's made this move. Perhaps the patrician home of Maria Thins was seen as a more fitting place to bring up the artist's growing family.

"With the exception of other artists in the guild with whom he had to maintain professional ties, there is little evidence to show that Vermeer entertained close contacts beyond the relatively segregated Papist's Corner, where he lived, condemned as a consequence of his Catholic marriage (and probable conversion to Catholicism) to second-class citizenship in a Protestant-dominated city."3

It is generally accepted that Vermeer, on his marriage to Catharina Bolnes converted to Catholicism and through the years seemed to have severed his ties with his own family through the years. His first born child was named Maria, after his mother-in-law and in the following years none of his many children were named after his own parents, an uncommon occurrence.

According to John Michael Montias, Maria Thins' house may be the furthest right-hand house (the highlighted area of image h. to the right) or the next house which continues off the right-hand side of the drawing.

(h.) Maria Thins house ?

Stadthuis (The Delft Town Hall)

The town hall was designed by Hendrick de Keyser using bits from the former court of the Court of Holland that stood at this location, most notably its tower. The rest of the building, built between 1618 and 1620, is a fine example of Mannerist architecture with a richly decorated front.

The marriage bans of Vermeer and his wife Catharina Bolnes were published in the Town Hall.

- For an extended discussion see M. P. van Maarseveen (1996) Vermeer of Delft: His Life and Times, Stedelijk Museum het Prinsenhof, Delft and Bekking Publishers, Amersfoort, Chapter 6, 'Where was Vermeer's Little Street?' In 1922 the town's municipal archivist L.G.N. Bouricius suggested No 25 Oude Langendijk, on the corner of the Molenpoort, the house believed by Swillens to have belonged to Maria Thins. Montias has since argued that Swillens was incorrect (see Vermeer’s Camera, The Truth behind the Masterpeices, Chapter 5). In 1948 J.H. Oosterloo proposed No 1 Spieringstraat, a house which is not however of sufficiently early date. Other writers have identified No 22 Vlamingstraat, and Nos 22-26 Nieuwe Langendijk, but with no very strong justification. (note from page five of Philip Steadman's online essay, A photograph of ‘The Little Street’ http://www.vermeerscamera.co.uk/essay5.htm)

- Philip Steadman, Vermeer and the Camera Obscura: The Truth behind the Masterpieces, 2002

- John Michael Montias, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History

, Princeton, 1989

The Town Hall of Delft